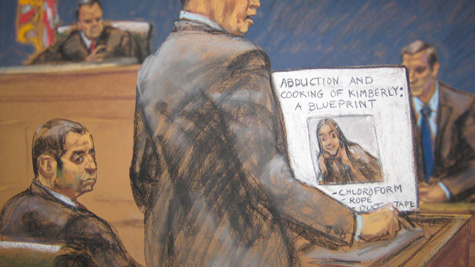

But Valle never actually did those things… well, he hasn't yet. Maybe he never would have and never will. That's an open question, answerable only by Valle. However, a recent Huffington Post article by Clay Calvert explains how Valle's resulting conviction for conspiracy to commit kidnapping will be argued this month in an appeal before the Second Circuit, a case which attorney Alan Dershowitz considers nothing less than “the future of the preventive state.” So the next question, one which our society and legal system must answer, is: What should we do pre-emptively, if anything, about the expression of such inclinations?

In 1785, the Marquis de Sade penned a twisted and bloodthirsty catalog of depravity called 120 Days of Sodom, or the School of Libertinism from his prison cell in the Bastille. In de Sade's story, four wealthy reprobates stock a remote castle with provisions and sex slaves, who include their own daughters. They're indulging in a four-month orgy designed to escalate until culminating in the erotic (?) slaughter of all the chattel, some of whom they intended to be pregant by that date so they can earn double-scores or something. This work, not widely available until the 20th century, has been condemned as pornography, praised as a blackly-humorous response to the Enlightenment, and treated as a subject for grim scientific research.

At the time it was written, it's said de Sade, far from engaging in the hedonistic revelries he scribbled, was suffering with uncontrolled gout and not quite enough money to bribe his jailers for better comforts.

De Sade's fetishistic writings have, however, been cited in court as the incitement to later criminality. In court, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley blamed his works for inspiring their torture and killing of what's now believed to be five children in the infamous Moors Murders of the 1960s near Manchester, England. It was demonstrated that the pair wasn't that conversant with de Sade, so did his explorations genuinely inspire their monstrousness, or were his expressed fantasies just their (defense representation's) desperate excuse?

Rachel Aviv's article “The Science of Sex Abuse” in The New Yorker discusses how one man immersed himself in the teeming online world of child pornography, and, therefore, started to feel less estranged by his impulses, ones he knew were illegal to act upon. “John” told a “girl” in a chat room about other underage girls, as young as ten, with whom he'd had sex. He was arrested by cops and feds after showing up to meet Indy-Girl and her supposedly fourteen year-old sister.

Indy-Girl was always a cop, who'd worked extensively to maintain the relationship on “her” side as well, the idea being to catch John before he hurt a real child. It was later discovered that what John had said online about his prior criminal conquests of children (and probably his weight and income, right?) were lies, intended to impress. He came to a staged picnic with what were likely illegal intentions, but ones he never acted upon, or had ever acted upon in the past as far as anyone knows. Is it easy to determine society's proper punishment for that?

John’s mother was a member of the local Day Lily Club, and spent much of her free time in her garden, where she had seven hundred and fifty varieties of lilies, whose growth she documented in scrapbooks. Warm and self-deprecating, she said that she identified with John’s tendency to become compulsively immersed in his hobbies. He’d spent long periods of his life absorbed in role-playing games, like Dungeons & Dragons—he became so caught up in this world that he nearly flunked out of college—and the Society for Creative Anachronism, a club that reënacts aspects of medieval culture. His mother believed that John might have ignored Indy-Girl if only he’d been less “prone to fantasy.”

… According to the largest study of released prisoners, conducted by the Bureau of Justice, the re-arrest rate for sex offenders is lower than that for perpetrators of any violent crime except murder. But the notion that sex offenders have a unique lack of self-control has been repeated so frequently that it has come to feel like common sense.

It seems as if the criminal justice system wasn't sure what to believe about John either, because he would later be refused release out of an abundance of concern of what he might do, “for a crime I have not yet committed.”

The notion of punishing Thought Crimes—or Precrime, if you're a Philip K. Dick fan—brings up a handful of topics worth chewing on. (Sorry, cannibal story, it's an irresistible impulse):

1) In the modern world, factual truths may be treated as lies, and many online lies are accepted and promulgated as truth (especially quotable, hashtaggable truth *raises hand in guilt at loving a clickable headline*). Maybe lying and sloganeering isn't anything new to humanity, but technology has made its manifestation instant, widespread, and persistent. Has the lack of context in bite-sized communications and ubiquitous thumbs-up-and-down judgments caused people to forget how complex the situations surrounding us can be?

2) Do we concretely know whether energy spent expressing socially-abhorrent and/or criminal fantasies helps alleviate or subvert the behaviors in question versus rationalizing them or providing encouragement?

3) Like all of us, people with impulses towards violent acts against others exhibit tendencies toward self-regard, self-preservation, and self-justification. These have to be weighed along with their self-reporting of what they meant, actually did, or would never do.

4) Without knowing the pressures and circumstances of the future, how accurately can someone forecast the dimensions of their behaviors or its limits? Can you… 100%? (Isn't this what entire horror movie franchises are based on—coming up with contexts that will force someone into the previously unthinkable?) How much of an excuse does someone already inclined need? For our society, is that vaporous level of uncertainty, that unknowable risk, enough to deprive some people of freedom for the rest of their lives?

5) Many crime fans vicariously spectate upon scores of heinous criminal acts daily and discuss them online, too. (Just like I'm doing now… don't rat me out!) Does that mean we're all monsters in the making, or that this bandying of the horrific causes us to minimize real harm, or to be any more likely to blur the line between make-believe and real-life?

Hmmm. Let me get back to you after Thought Crimes: The Case of the Cannibal Cop, premiering Monday, May 11th at 9p, Eastern.

Clare Toohey is a literary omnivore and freethinker who despises cannibals. Aside from editing The M.O. and site wrangling here, she freelances as as editor, writes short, surreal crime fiction, blogs at Women of Mystery, and tweets @clare2e.