In our series on Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, we looked at the films the great screen duo made between 1944 and 1948. After 1948, however, the two never made another movie together. (Though they did star in the radio adventure series Bold Venture in 1951 and worked together on a 1955 television production of The Petrified Forest.) In the late forties and early fifties, Betty (her real name; no one ever called her Lauren) slowed down her participation in films to raise two children with Bogart. After Bogie died in 1957, her career slowed even further. Part of this was due to her close association with her former screen partner, of course. In the public mind, she was “And Bacall.” In some respects—as Bacall herself often pointed out—she never fully had a career of her own. The massive overnight success of her entrance into movies, and her connection with Bogart’s legacy, was its own kind of show business prison.

What this obscures, of course, was that Bacall was always a striking screen presence and a serious actor from the very beginning. Here then is a look at some of her most interesting films from the fifties onward.

Young Man With A Horn (1950) and Bright Leaf (1950)—After being away from movies since 1948 to have her first child, Bacall bounced back in two pictures helmed by the great Michael Curtiz. In Young Man With A Horn, she starred opposite Kirk Douglas and Doris Day in a drama written by Carl Foreman and Edmond North (from a novel by Dorothy Baker) about the rocky marriage between a jazz cornetist (Douglas) and a would-be psychologist (Bacall). In Bright Leaf, Bacall plays a bordello owner in love with a tobacco magnate played by Gary Cooper. Two very different films, but Bacall is excellent in both. In her emotional tug-of-war with Douglas (at his self-hating rageaholic best) she’s slow-boiling and intense, threatening to him because of her cold intelligence. Opposite Cooper, though, she’s airier, with a bit of the quick-witted spunk that had made her early Howard Hawks films fun. After telling her he’s been “up in Boston learning things,” Cooper kisses her, and she quips, “If you learned that in Boston, I’m going north.”

Young Man With A Horn (1950) and Bright Leaf (1950)—After being away from movies since 1948 to have her first child, Bacall bounced back in two pictures helmed by the great Michael Curtiz. In Young Man With A Horn, she starred opposite Kirk Douglas and Doris Day in a drama written by Carl Foreman and Edmond North (from a novel by Dorothy Baker) about the rocky marriage between a jazz cornetist (Douglas) and a would-be psychologist (Bacall). In Bright Leaf, Bacall plays a bordello owner in love with a tobacco magnate played by Gary Cooper. Two very different films, but Bacall is excellent in both. In her emotional tug-of-war with Douglas (at his self-hating rageaholic best) she’s slow-boiling and intense, threatening to him because of her cold intelligence. Opposite Cooper, though, she’s airier, with a bit of the quick-witted spunk that had made her early Howard Hawks films fun. After telling her he’s been “up in Boston learning things,” Cooper kisses her, and she quips, “If you learned that in Boston, I’m going north.”

How To Marry A Millionaire (1953)—After another two year absence, during which time she gave birth to her second child, Bacall teamed up with Marilyn Monroe and Betty Grable for the first Cinemascope romantic comedy, How To Marry A Millionaire, about three women who rent a fancy New York apartment in an attempt the land rich husbands. A victim of the early fifties television-phobic trend toward bigness, the film suffers from a sense of inflation (we get an onscreen orchestral overture, for example, purely to help justify the bigger-is-better ethos), but the movie is above all a triumph of typecasting. Grable is goofy, Monroe is goofy-but-sexy, and Bacall is the smartass. Watching these three trade quips is pure joy. Bacall’s comedic chops have a nicely hardboiled bite, too—like when she tells Monroe, “Most women use more brains picking a horse in the third at Belmont than they do picking a husband.”

Written On The Wind (1956)—Bacall starred opposite Rock Hudson, Dorothy Malone, and Robert Stack in one of Douglas Sirk’s milestone fifties melodramas. The picture really belongs to Bacall’s old Big Sleep co-star Malone, who gets to put the vamp in vamping-it-up. Bacall has the more unenviable role as the good girl who is torn between Hudson and Stack.

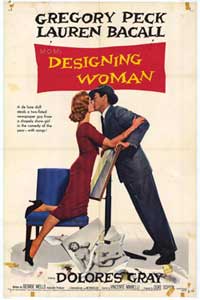

Designing Woman (1957)—Bacall paired up with Gregory Peck and director Vincent Minnelli for this fun He Said/She Said romantic comedy about a fashion designer (Bacall) who meets and marries a sportswriter (Peck) only to discover that while opposites may attract, opposites may also have a hard time living together. In some ways, this film marked the end of Bacall’s A-list career. Bogart was dying during filming, and Designing Woman underperformed. A few more leading parts would follow, but the pictures got smaller in scope and fewer in number. Of course, Hollywood itself was rapidly changing in the late fifties, and Betty Bacall—though only thirty-three—already seemed like yesterday’s news, a living museum piece of a Hollywood that was, for all intents and purposes, already gone. Bacall was a survivor though. There would be other parts, other work to be had.

Designing Woman (1957)—Bacall paired up with Gregory Peck and director Vincent Minnelli for this fun He Said/She Said romantic comedy about a fashion designer (Bacall) who meets and marries a sportswriter (Peck) only to discover that while opposites may attract, opposites may also have a hard time living together. In some ways, this film marked the end of Bacall’s A-list career. Bogart was dying during filming, and Designing Woman underperformed. A few more leading parts would follow, but the pictures got smaller in scope and fewer in number. Of course, Hollywood itself was rapidly changing in the late fifties, and Betty Bacall—though only thirty-three—already seemed like yesterday’s news, a living museum piece of a Hollywood that was, for all intents and purposes, already gone. Bacall was a survivor though. There would be other parts, other work to be had.

Harper (1966)—William Goldman adapted the Ross Macdonald novel The Moving Target, with Paul Newman playing the (renamed) Lew Archer. Macdonald’s Archer was, of course, a direct, conscious, descendent of the Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler roles that helped make Bogart a noir icon, so Bacall’s presence here as Archer’s caustic employer is something of a callback to the hallowed days of classic noir. Bacall is as excellent as ever. Told that her husband has been kidnapped by some unsavory associates, she sneers, “Oh, he loves playing the family man, but he never fooled me. Water seeks its own level, and that should leave Ralph bathing somewhere in a sewer.”

Applause (1970)—Bacall’s great comeback wasn’t on film but on Broadway, when she took up the role of Margo Channing in the musical adaption of All About Eve. Applause was a smash hit, playing for 896 performances and winning a slate of awards, including a Tony for Best Performance for Bacall. While it was never adapted into a movie (which is a damn shame), it was broadcast on television in 1973, with Bacall reprising her role.

The Shootist (1976)—After 1974’s Murder On The Orient Express (a fun, if overstuffed, Agatha Christie adaptation that lumped Bacall in with a dozen other stars including, most notably, Ingrid Bergman), Bacall increasingly took on the role of old Hollywood representative. You see this most clearly in John Wayne’s final film, The Shootist, where Bacall plays a stern but good-hearted widow who sees Wayne’s dying gunman through his final days. Since Bacall was as much a woman of the Left as Wayne was a man of the Right (Bacall had helped lead a failed attempt to stop the Communist witch hunts of the 1950s that Wayne had openly encouraged), it was assumed by some that they would be at odds. They had worked together before, however, back in 1955 on the adventure film Blood Alley, and had always enjoyed warm relations. You can see this warmth in The Shootist. Everything about Betty Bacall read as strength, and Wayne had always responded to strong leading ladies. Their scenes together are the best thing about an excellent film.

We’re about out of space here, but let us know if there are any great Bacall performances that we’ve missed!

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor, is the author of The Posthumous Man and Saint Homicide.

Read all posts by Jake Hinkson for Criminal Element.

Bacall did a film with James Garner in the eighties called “The Fan” that I really enjoyed. Much better than the Wesley Snipes/Rober DeNiro remake.