We Sherlock Holmes fanatics are suckers for references (direct or indirect, even vague nods, some of us aren’t terribly picky) to the original stories. John Watson suffered one, possibly two, wounds in Afghanistan. Sherlock Holmes keeps tobacco in his Persian slipper. The dog in the nighttime was innocent of any wrongdoing—or action, for that matter. Sherlock Holmes is a jackass, but a jackass whom we love. He solves crimes, yes, but he also determines via the electric intuition of his own (and sometimes John Watson’s) conscience whether or not the criminal should be punished for the crime. Examples, should one choose to doubt this assertion:

We Sherlock Holmes fanatics are suckers for references (direct or indirect, even vague nods, some of us aren’t terribly picky) to the original stories. John Watson suffered one, possibly two, wounds in Afghanistan. Sherlock Holmes keeps tobacco in his Persian slipper. The dog in the nighttime was innocent of any wrongdoing—or action, for that matter. Sherlock Holmes is a jackass, but a jackass whom we love. He solves crimes, yes, but he also determines via the electric intuition of his own (and sometimes John Watson’s) conscience whether or not the criminal should be punished for the crime. Examples, should one choose to doubt this assertion:

- Is a father-in-law determined to carry on his false relationship with his daughter-by-marriage so he can keep her inheritance a man who deserves to horsewhipped? (Holmes says: yes.)

- Is a man who stole a goose for profit likely to go wrong again if you scare the trousers off his mealy little arse? (Holmes says: no.)

- Is a man who killed a wife-beater and sadist—a sadist who incidentally set his spouse’s dog on fire and killed it to teach her a lesson—guilty of murder when he murders that sadist in arguable self-defense? (Holmes says: no.)

The Sherlock episode “His Last Vow” has absolutely everything to do with this issue of independent moral standing and justice execution. I would argue that the extent to which the characters in the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes justify their own questionable actions is very important, and I would likewise posit that nowhere is this conundrum better exemplified canonically than in “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton.”

Sherlock Holmes greatly enjoys categorizing things. Tobacco ash, for a start. Mud. The man is a virtuoso in mud studies. Probably also twigs. And pigeon feces. (I am merely extrapolating from known data, and should be clear this is unconfirmed in the canon—but Sherlock Holmes could probably glance at pigeon crap and determine the whereabouts of the bird’s last meal.) Additionally, however, he adores categorizing humans, and I sometimes wonder if he is so very deeply fond of John Watson because John Watson cannot ever be definitively categorized. The smartest men in London, the wickedest men in London, the most beautiful women and the most charitable of ugly men—Holmes has certain standards and systems, and he lives by these rules.

Charles Augustus Milverton? He is “the worst man in London.” The most nefarious, you might wonder, the organizer of half that is evil and nearly all that in undetected in the great metropolis? No, that was James (or Jim, as the BBC would have him) Moriarty, with whom Holmes always shared a special something.

The worst man in London is another kettle of snakes.

Editor's note: Spoilers and slitherers ahead, you know.

BBC Sherlock’s version of this canonically described viper—screenwriter Steven Moffat uses a slightly more modern “shark” comparison for Charles Augustus Magnussen, who could legitimately be featured in Shark Week as played by the terrifying Lars Mikkelsen—is, quite frankly, disgusting. He is disgusting in the opening moments of the episode, radiating disdain at a room full of politicians questioning whether a media mogul should have quite so much control over Whitehall. He is disgusting when he paws all over his first blackmail victim, Lady Smallwood, with medical-grade sweaty palms. He is extremely disgusting when he licks her face. He is likewise disgusting peeing in Sherlock’s fireplace, another disgust-invoking moment occurs when he picks an olive out of Sherlock’s pasta and then washes his fingers in the detective’s water glass, and all of the most egregious instances involve him being not the Napoleon of Crime, but rather the worst man in London—a man who (in unflattering nods to Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch) doesn’t need evidence to procure a prosecution. The popular tabloid press is enough of a weapon in and of itself.

BBC Sherlock’s version of this canonically described viper—screenwriter Steven Moffat uses a slightly more modern “shark” comparison for Charles Augustus Magnussen, who could legitimately be featured in Shark Week as played by the terrifying Lars Mikkelsen—is, quite frankly, disgusting. He is disgusting in the opening moments of the episode, radiating disdain at a room full of politicians questioning whether a media mogul should have quite so much control over Whitehall. He is disgusting when he paws all over his first blackmail victim, Lady Smallwood, with medical-grade sweaty palms. He is extremely disgusting when he licks her face. He is likewise disgusting peeing in Sherlock’s fireplace, another disgust-invoking moment occurs when he picks an olive out of Sherlock’s pasta and then washes his fingers in the detective’s water glass, and all of the most egregious instances involve him being not the Napoleon of Crime, but rather the worst man in London—a man who (in unflattering nods to Ted Turner and Rupert Murdoch) doesn’t need evidence to procure a prosecution. The popular tabloid press is enough of a weapon in and of itself.

Remarkably timely on the part of the Sherlock team, and remarkably apt, considering that the real Master Blackmailer was known to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (look up Charles Augustus Howell, an art collector and predator who hounded painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti among many others). The devastating immediacy with which this villain identifies every base impulse leaves his victims utterly impotent. You have a porn preference? Magnussen has it on file. You have a gambling weakness? He has likewise catalogued it. Did you ever swear at your mamma? He knows. You have a strange affinity for unripe bananas? Magnussen is the ultimate incarnation of the everyone can see you doing everything you’re ashamed of, even Ceiling Cat trope, and he is by default a loathsome human since he’s enjoying the foibles of others and then profiting by them.

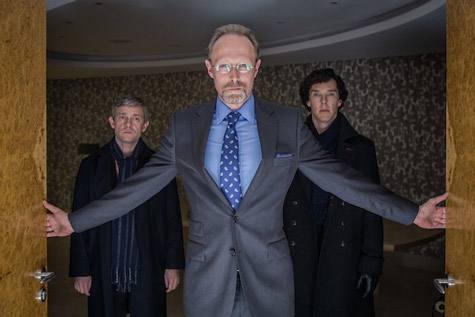

The riveting Lars Mikkelsen is not just a loathsome baddie, he is a gleefully sadistic one. But then, the Sherlock engine has always had superb casting on its side, and Benedict Cumberbatch, Martin Freeman, and Amanda Abbington likewise show more of their considerable, pooled acting chops in this episode, one which is not very likely to leave the fan quietly sipping herbal tea and calmly chatting over what they would like to see in the next season. This is heartbreaking material, and the fact we were waiting so long for the inevitable climax only added to the inherent drama of the season’s arc.

Especially when faced with so worthy a foe as Magnussen. In the canon, Holmes and Watson burgle his house and watch a woman shoot him point-blank five times, slow-clapping her as they emerge from behind a curtain. In the episode, rather more goes on—but you get the gist of our sentiments toward this son of a shark.

Sherlock is discovered (in almost identical cricumstances to “The Man with the Twisted Lip”) lazing about in a drug den when John—seemingly happily married, a little too happily, a little happy McHappy when he’d prefer to have a bit of darkness to thwart—finds his old friend there following a month’s lack of communication. What follows is a dizzying washing machine of Doylean references. Wiggins, the unofficial head of the Baker Street Irregulars, Holmes’s band of street urchins? Check—he’s a key part of Sherlock’s Homeless Network. Billy the page, as featured in “The Mazarin Stone” and once upon a time played by one of the world’s great comic actors? (Tweet me the trivia and I’ll mail you a cookie.) Same dude, Billy Wiggins, who is crashing in the crack house in which hapless druggie neighbor Isaac Whitney finds himself. Mary Watson is asked by John to stay home as he retrieves their acquaintance, since she’s pregnant.

Here the show takes a sharp curve. And as a woman who likes to decide whether she does or doesn’t wish to stay home, I greatly enjoyed the transformation of John Watson’s sweet, intelligent Victorian wife into someone rather…well…hmmm.

The verdict, until Series Four, is yet out, I fear.

Of course, hetero-normative happiness isn’t exactly the raison d’etre of this series. I cannot understate the value of Martin Freeman’s incredulous John reacting to Cumberbatch’s Sherlock, when the sleuth is newly exposed to be in a state of domestic bliss. John might as well have been staring at a unicorn-shaped space vessel landing as Sherlock kissing a girl of all things. Sherlock turns out to be fooling Janine-the-Bridesmaid from “The Sign of Three,” and we know this is par for the course, as he likewise got himself engaged to Charles Augustus Milverton’s housemaid “Agatha” in the short stories. However, watching the rapport between Freeman and Cumberbatch has always been akin to watching a backdraft explosion, and the comic potential in Sherlock’s newfound cuddly phase isn’t to be underestimated. It’s a light moment in a dark episode, and we appreciate it, because trust me: night falls pretty damn quickly in these parts.

So let’s say you’re Sherlock Holmes, and you know your best bro has a bit of an adrenaline addiction, but that only solidifies your friendship and you’ve embraced the quirk as near and dear to your heart. You die, but then you return, only to find that the only person who apparently understands you and your severe compartmentalization issues is a seemingly innocuous blonde, the fiancée of aforementioned best bro, who by the way reads as “cat lover,” “nurse,” and “liar,” when her physical tells are examined through observation and deduction.  You deal with the loss of your friend’s immediate company and delegate his chair to the attic because you really really don’t like seeing it empty. Really. At all. You slip sidelong into dangerous habits despite the fact you are drawn to his fiancée and have decided she is more worthy of his company than you are.

You deal with the loss of your friend’s immediate company and delegate his chair to the attic because you really really don’t like seeing it empty. Really. At all. You slip sidelong into dangerous habits despite the fact you are drawn to his fiancée and have decided she is more worthy of his company than you are.

You let things go a bit. Heroin ensues.

So alternately let’s say you’re John Watson, and you went to war to heal people, and you shot a murderous cabbie from an unlikely distance in “A Study in Pink,” seeing as it was to save a newfound friend. Fast-forward through that friend’s untimely (very untimely) death, fall in love, and then endure your friend’s untimely (very untimely) return. You forgive him and you step away for safety’s sake and you allow him to be sorry and you continue with the life you’ve forged. You impregnate your gorgeous and clever spouse. You are happy, or maybe you think you should be happy, or maybe you are in fact delighted, but would appreciate a little more gunplay on any given Thursday, and you forget your best friend is a self-proclaimed (too often) sociopath who thinks of illicit drugs the way some people think of Skittles. Meanwhile, every so often your wife is cleverer than you imagined. Daaaaaaangerously clever…

You let things go a bit. Vigilante-style assault in a crack den ensues.

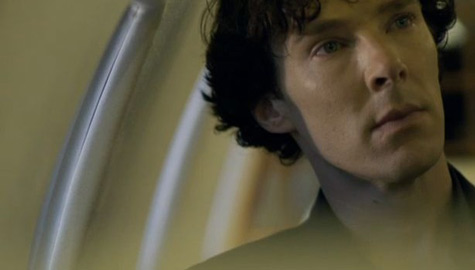

Mary Watson, nee Morstan, shoots Sherlock Holmes in the chest not so very far into “His Last Vow.” What follows are a series of confrontations, many of them canonical and some of them ridiculously fun. Watson’s wife was never classically an ex-CIA operative threatened by a foul blackmailer, but you know what, this new Mary is a damn good sport, by Jove. The scene in which Sherlock retreats into his Mind Palace to survive the attack is almost absurdly well-written, a telling exploration into the workings of an eccentric mind and its many dusty corridors. If you (the viewer) ever gets shot, you ought to deduce whether or not you have an exit wound, what falling posture would allow you to bleed the least, refuse to go into shock by means of recalling a beautifully nostalgic household pet, and then allow your subconscious (in the form of your great nemesis Jim Moriarty) to shriek your way out of trouble.

Trust me. It’ll work. It sounds ludicrous, but it works in this episode like a luxury KitchenAid mixer, and by that, I am legitimately saying something.

Only problem is, Mary didn’t mean to shoot Sherlock, never out of malice—il miglior fabbro, my double, my brother—and thus Sherlock the Equally Lunatic Admirer of John Watson sets about first proving Mary guilty to his friend by means of a fabulous “The Adventure of the Empty House” sequence in which John serves as the living wax bust of Sherlock. Then Sherlock proves her innocent by dragging them both back to Baker Street to fix the marriage he is convinced they all need, whilst meanwhile Sherlock is incidentally bleeding to death. I can’t write this review without the high drama sounding crackity crack-crackers, but somehow it isn’t; somehow, it’s about three flawed people trying to build something, and being gutted when their castles in the sand are washed away. No matter which of the relationships you’re invested in, you’re drawn to Sherlock, John, and Mary’s unlikely trio in that there is no one in this dull sphere who thinks quite like we do, who understands the beauty of desperation and chaos and danger, and that is wonderfully sad and wonderfully pretty all at the same time. The sign of three, indeed.

The supporting cast are granted myriad moments to shine. Rupert Graves as Greg Lestrade is given little to do in “His Last Vow,” but he is brought into the storyline as indispensable, and one appreciates that. Loo Brealey as Molly Hooper practically gives Sherlock a concussion when she finds out he’s been using again—a moment not to be missed for worlds. Mark Gatiss as the oily Mycroft Holmes shines bright once more, a walking tribute to bureaucracy who can still confess to his little brother that the elder one’s heart in is his hands, and look not remotely embarrassed by this admission afterward.

The nitty gritty of “His Last Vow” will doubtless lie in the aftermath, in Series Four, and I alluded to it earlier—where is the moral compass these days? I adore grey areas, but I begin to fear for the casual observer’s conscience. John was once Justice’s scales, and now is a man caught between the lady assassin he loves and the friend he couldn’t bear to lose, a doctor who killed terrorists now floundering on the margins of the action. Mary was once a snarky, warm domestic ideal, and is now (thank heaven) a lady assassin, but one whose history we’re cheated of when John throws away the file. Sherlock is a nutbucket encased in a bag of rabid voles that was tossed into a dryer on spin cycle with paint fumes being pumped into the works—except that he now loves those whom he defines as his family, and unconditionally at that. What could be more admirable than this act, that you lay down your life for your brother?

It’s so satisfying. It’s a bit off, to be honest. Well, more than a bit. But…

I’m not saying the Sherlock Holmes of the canon never killed anyone. He did. For a fact. I’m saying that when Sherlock kills Magnussen in a semi-execution-style shot to the head, after a tour de force cat and mouse game in which many crosses are doubled and t’s crossed, the curly-haired misfit does it for family, at the same time he is announcing, “I’m not a hero—I’m a high-functioning sociopath. Merry Christmas!” This is the first time I’ve identified a line that was not merely tonally equal to the less insightful Judge Dredd dialog moments, but directly contradicting the theme that the show writers were conveying. Sherlock is no longer an island. Or if he is an island, he is Aruba. There are visitors. He profits by them. They scritch their toes in his sand and he offers them sunshine. To reduce all this to vengeful sociopathy is cheap—but then, these people are often kidding, and I like the lack of dourness they bring to deep moments of truth. I enjoy le kidding.

There is a twist end. La-la-la, they are hinting at the return of a mighty foe. Far more poignant is the moment when Sherlock, in a nearly-tearful farewell scene with John on airport tarmac that belongs in a Tom Hanks dramedy circa 1993, confesses his most heartfelt emotional turmoil over banishment and solitude actual first name, suggesting it might just work for the addition to the Watson family Mary is carrying.

But we know all of this already, the sentiment and the ache, though the scene is lovely. Sherlock Holmes always kills for very good reason, despite the fact that his murders inevitably lead to exile. Both in “His Last Vow” and in the canon, that one time he left a note and an alpine-stock leaning against a boulder, it was always for love, I think. Dubious actions aplenty, dubious motives few and far between.

So I raise my glass to Season Four, in the sincere hopes that the Sherlock folk carry on this new trend of innate nobility within their sexy psyche ward candidate, because I will be there with bells on. No matter which dragons Sherlock confronts, and believe you me, as he did Mycroft—here there be dragons.

Lyndsay Faye is the author of Dust and Shadow, also The Gods of Gotham and Seven for a Secret (September, 2013) in the Timothy Wilde series from Amy Einhorn Books/Putnam. She tweets @LyndsayFaye.