From its opening sentence, Cosmos by Witold Gombrowicz throws you off balance:

From its opening sentence, Cosmos by Witold Gombrowicz throws you off balance:

I’ll tell you about another adventure that’s even more strange.

Odd opening line, and a few pages later, the oddness continues. Our narrator and his companion Fuks are tramping through the woods somewhere in Eastern Europe looking for a cheap rooming house. Fuks says he knows of one nearby. It is hot, they are tired, and just off the forest path they come across something disturbing:

“A sparrow.”

“Ah.”

It was a sparrow. A sparrow hanging on a piece of wire. Hanged. Its little head to one side, its beak wide open. It was hanging on a thin wire hooked over a branch. Remarkable. A hanged bird. A hanged sparrow. The eccentricity of it clamored with a loud voice and pointed to a human hand that had torn into the thicket—but who? Who hanged it, why, for what reason?

And so our mystery has kicked off, and though the narrator (named Witold) and Fuks continue on to their rooming house and check in, they can’t shake from their minds the image of the hanging sparrow. In bed that night in the room he shares with Fuks, Witold suddenly realizes that he can’t hear Fuks breathing in the other bed. Where has Fuks gone?

But in that case…what if he had gone to see the sparrow? I don’t know why I thought of it, but I knew right away that this was quite possible, he could have gone, he had been interested in the sparrow, he was in the bushes looking for an explanation, his carroty, phlegmatic mug was just the thing for such a search, it was just like him….to ponder, to scheme, who hanged it, why did he hang it……anyway, he had awakened, or maybe he hadn’t gone to sleep at all, and, his curiosity piqued, he got up, maybe he went to check some detail and to look around in the night?…was he playing detective?…I was inclined to believe it. More and more I was inclined to believe it.

It’s clear we’re not in the realm of a conventional mystery novel, and in fact, Cosmos is not a genre work per se at all.

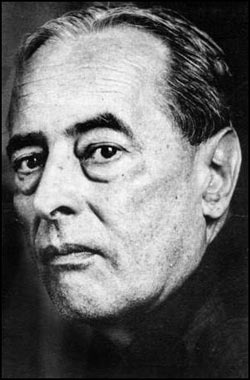

I hate the defining tags that limit a book to this or that category, but for the sake of simplicity, let’s call Cosmos a literary novel. Published in 1965, it’s the last of five novels written by Gombrowicz, a Polish-born author now considered a giant of twentieth-century literature. He’s a writer who’s drawn praise from Milan Kundera and John Updike, among others, and to put Cosmos in context, I’ll merely state that it won the Editor’s International Prize for Literature in 1967. At the time, the prize was second in prestige only to the Nobel Prize. A literary modernist, Gombrowicz wrote challenging books full of paradox and ambiguity, and there’s a frequent sense of the absurd in his narratives. Ironic twists and reversals abound and no wonder: he’s a man whose whole life hinged on a sudden unexpected turn.

Born in 1904, he began his writing career in Warsaw and achieved some prominence in Poland with the publication of his first novel, Ferdydurke, in 1937. Two years later, he accepted an invitation to go on the maiden voyage of a cruise ship sailing to Argentina. The plan was to stay two weeks in South America, but while he was in Buenos Aires, World War II broke out. The Nazis invaded Poland (and after them, the Soviets) and Gombrowicz found himself in Argentina speaking no Spanish and with no money. He remained in Argentina, and the intended short vacation turned into a twenty four year stay.  Though he worked for eight of those years as a bank clerk in Buenos Aires and over time established himself in the Argentine literary world, he never made any real money. He spent his twenty four years in Argentina impoverished. Yet as he later wrote….. “if by some quirk of fate the war had not broken out during those two weeks, I would have returned to Poland—but I did not conceal that when the door was bolted and I was locked in Argentina, it was as if I had finally heard my own voice.”

Though he worked for eight of those years as a bank clerk in Buenos Aires and over time established himself in the Argentine literary world, he never made any real money. He spent his twenty four years in Argentina impoverished. Yet as he later wrote….. “if by some quirk of fate the war had not broken out during those two weeks, I would have returned to Poland—but I did not conceal that when the door was bolted and I was locked in Argentina, it was as if I had finally heard my own voice.”

That voice, serious but playful, revels in satire and parody. Gombrowicz enjoys turning literary conventions inside out. In Cosmos, it’s the detective novel he’s messing with, and I’ve picked it as a book to look at because it’s a prime example of a non-genre writer using the detective story format in an inventive way.

The usual mystery plot moves from disruption to order. A crime or series of crimes creates an imbalance in the fabric of things. The investigator’s solution restores balance, if only within the circumscribed world of the novel or story the person’s reading. This restoration of balance is one of the time-honored attractions of the mystery story, an undeniable reason for the genre’s popularity. The world outside may be chaotic and random, with questions that never get answered, motives that can’t be explained, and crimes that don’t get solved, but read a good mystery and the damndest puzzles, the weirdest psychological motivations, end up as understandable.

A coherent solution provides comfort to the reader; for the mystery addict this is a comfort sought out again and again and appeased only by the consumption of yet more mysteries. It never gets old to see the process by which an investigation proceeds and clues are found and interpreted. From a wide variety of possible explanations, we narrow down to one definitive answer. But what about a mystery that works in reverse? What if one small act, maybe not even a crime, opens out to a bewildering chain of events? What if one bizarre discovery leads to a dizzying abundance of clues? Cosmos is a novel that follows this principle.

After the incident with the hanging sparrow, our protagonists Witold and Fuks notice what Fuks takes to be an arrow-shaped mark on the ceiling of their bedroom. It draws his immediate suspicion because it resembles a similar mark Witold had seen earlier in a corner of the dining room. Fuks is convinced the bedroom arrow points in the same direction as the dining room arrow. And if it’s an arrow, as he says, “it must be pointing at something.”

Witold’s answer: “And if it’s not an arrow, it’s not pointing.”

These two curious gentlemen know they may be seeing patterns that don’t exist, but they can’t help themselves. They pursue the lead they believe they’ve found by walking in the direction they think the bedroom arrow is pointing, and lo and behold, they wind up outside, in the rooming house’s overgrown garden, where they find nothing less than a hanging stick. It’s a “small stick, about an inch long. It hung on a white thread, not much longer. It was hitched over a jagged brick.”

Back in their room, the two discuss their findings, and they sound like nothing less than a private eye team:

“Say what you will, but the arrow has led us to something,” he said warily, and I, no less warily, muttered, “Like what?”

Yet it was hard to pretend that one didn’t know: a hanged sparrow—a hanged stick—the hanging of the stick from the wall repeating the hanging in the thicket, a grotesque result that suddenly increased the sparrow’s intensity………The stick and the sparrow, the sparrow reinforced by the stick! It was hard not to think that someone had led us to the stick to make us see a connection with the sparrow….but why? What for? As a joke? A prank? Someone had played a trick on us, made fools of us, to amuse himself…I felt uneasy, Fuks felt it too, and this prompted caution.

The two in fact are in an isolated rooming house with a limited cast of characters, just as in a conventional country house mystery. They talk about everyone else there with them, considering each as a potential suspect, speculating as to motives. The perpetrator must be there among them, they conclude, but whenever a sense of certainty hits, both retreat to the acknowledgment that what they are investigating could be meaningless. Witold’s narration is rife with ambivalence:

Yet it didn’t make sense. Who would want to play such elaborate jokes? What for? Who could have known that we’d discover the arrow and take such a deep interest in it? No—this concurrence, however small, between the stick on the thread and the sparrow on the wire—was pure chance. Granted, a stick on a thread, one doesn’t see this every day…yet the stick could have been hanging there for a thousand reasons unrelated to the sparrow, we had exaggerated its importance because it turned up at the end point of our search as its outcome—when in fact it wasn’t any outcome at all, it was just a stick hanging on a thread…Pure chance then? Indeed….and yet one could sense in this series of events, a propensity for congruity, something hazily linking them together—the hanged sparrow—the hanged chicken—the arrow in the dining room—the arrow in our room—the stick hanging on a thread—something was trying to break through and press toward meaning, as in charades, when letters begin to make their way toward forming a word. What word? Indeed, it seemed that everything wanted to act in the name of an idea…What idea?

Is it possible for a detective to ask too many questions? To interrogate suspects and form suppositions are a large part of what a detective does, but shouldn’t all the inquiring and theorizing lead in the direction of clarity about the situation? In a typical detective story, they do, but not in Cosmos. Though Fuks pretty much abandons the case, becoming a little distant from the narrator and involving himself more in the romantic intrigues taking place in

What detective worth his salt doesn’t have eccentricities? But what we come to realize is that our narrator in Cosmos has no clear-cut sense of scale. As Sherlock Holmes says in “The Reigate Puzzle”: “It is of the highest importance in the art of detection to be able to recognize out of a number of facts which are incidental and which are vital. Otherwise your energy and attention must be dissipated instead of being concentrated.”

Witold, to his credit, knows himself; he says that he is “inclined to trivialities” and that he’s “fragmented…oh, I was so fragmented…” But this doesn’t stop him from seeing signs and clues everywhere. And the result is that instead of separating threads and solving a particular crime, imposing rationality on seemingly irrational events, he winds up entangled in his own mental world. He invests the banal objects around him with threat, the simplest gestures and expressions of the people around him with pretense and intrigue. For Witold, everything seems connected to everything else, and through this worldview, we recognize that he’s dangerously close to being an outright paranoid.

Witold Gombrowicz called Cosmos “a novel about a reality that is creating itself.” He also said that since the detective novel is explicitly about the “attempt at organizing chaos,” he gave the book a little of the “form of a detective romance.” The form, but not the intent. Because as Witold, the character, becomes caught up in the minutia of daily life, seeing possible signs and connections everywhere, he becomes increasingly bothered at his inability to discern an overarching mystery that he can solve. While he sees a number of fuzzy patterns, he sees no one defining pattern.

Reality itself is indeed the great mystery, and his exasperation with reality leads him at last to commit a crime. The crime he commits will make a meaningful pattern exist where none existed before, and it will be a crime he can most certainly solve (what a relief) since he knows who did it.

“Don’t you know anything?” [Witold is asked]. “Who, how? Haven’t you noticed anything.”

No, I haven’t, late last night I took a walk, I returned well after midnight and came in through the porch, I don’t have any idea whether the cat was already hanging—my delight at misleading them grew in step with this deceitful deposition, I was no longer with them but against them, on the other side. As if the cat had transferred me from one side of the medal to the other, into another sphere where mysteries happened, into the sphere of the hieroglyph. No, I was no longer with them. Laughter tickled me as I watched Fuks laboriously looking for signs by the wall and attentively listening to my lies.

I knew the mystery of the cat. I was the perpetrator.

At least somebody is. Now we have a criminal we can point to. Not that his killing of the cat ends the novel. Witold still has to undergo a string of absurd conversations using nonsense words his fellow vacationers speak, and soon a person will be found dead, suspended from a tree by his own belt. The brief relief Witold got from hanging the cat and fulfilling a pattern—hanging sparrow, hanging stick, hanging cat—evaporates when he sees the corpse. He knows he didn’t commit this crime and so the questions start in him again. Who did it? Why? And what’s the connection to the earlier acts involving the sparrow and the stick (though not the cat)?

A multitude of possibilities swirls through his addled brain; language itself is no help; day to day life, even when it’s prosaic on the surface, is actually an unending struggle with chaos. And the reader? Well, you may experience a touch of frustration hoping that Witold has a breakthrough, but you’ll be laughing despite yourself at his confusion and turmoil. Gombrowicz is nothing if not very funny.

Do I have to point out what by now must be obvious? The reader doesn’t finish Cosmos with a feeling of closure. Nothing absolute will be solved. Anyone who has bent the detective story rules this much isn’t going to follow the rules at the end. But Cosmos provides a wonderful example of a genre form constructively abused by an idiosyncratic author. As Gombrowicz said of himself: “I am a humorist, a clown, a tightrope walker, a provocateur, my works stand on their head to please, I am a circus, lyricism, poetry, terror, struggle, fun and games—what more do you want?”

Uh, not much really.

Is Gombrowicz’s Cosmos all that he says it is? Yes.

Is it worth exploring? Absolutely.

Delve in.

Scott Adlerberg lives in New York City. A film nut as well as a writer, he co-hosts the Word for Word Reel Talks film commentary series each summer at the HBO Bryant Park Summer Film Festival in Manhattan. He blogs about books, movies, and writing at Scott Adlerberg’s Mysterious Island. His Martinique-set crime novel, Spiders and Flies, is available now from Harvard Square editions at Amazon, B&N, and wherever books are sold.

Read all posts by Scott Adlerberg for Criminal Element.

Great stuff, Scott. This is new to me, and I’m going to check it out. I’ll let you know how it goes.

Thanks, Jake. I’ll be curious to hear what you think of the book.

Congratulations, Mr. Adlerberg! Your text is so good it was fully used in the cover of Cosmos’ brazilian edition. Don’t forget to claim your royalties!

Strange to hear, Harold. But if true, thanks for the heads-up.