Sometimes a great story can be told when there’s not much of a story to tell. That sounds wrong, I know, but think about Jim Jarmusch’s 1984 art house classic film Stranger Than Paradise. That movie is mainly about two lovable losers, Willie and Eddie, whose idea of Saturday night fun is sitting around Willie’s crummy New York City efficiency apartment, not talking to each other while swilling cans of cheap beer and watching the paint crack off the walls.

Sometimes a great story can be told when there’s not much of a story to tell. That sounds wrong, I know, but think about Jim Jarmusch’s 1984 art house classic film Stranger Than Paradise. That movie is mainly about two lovable losers, Willie and Eddie, whose idea of Saturday night fun is sitting around Willie’s crummy New York City efficiency apartment, not talking to each other while swilling cans of cheap beer and watching the paint crack off the walls.

Okay, okay, some things do happen to those jokers in the tale—Willie’s Screamin’ Jay Hawkins-obsessed cousin from Budapest comes for a visit, Willie and Eddie win some loot in a crooked card game, Willie and Eddie later go to Cleveland and Florida…but, come on, we’re not talking about thrilling lives here. Yet that movie is brilliant, and utterly compelling. It’s the atmosphere, stupid. And showing people as they really are.

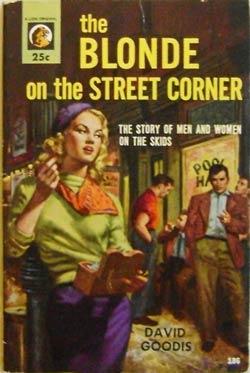

The Blonde on the Street Corner, David Goodis’s underground classic of noir fiction, has this same duality of being both punishingly humdrum yet completely engaging.

Published in 1954 but set in 1936, TBOTSC centers on a quartet of shiftless friends from Philadelphia. Willie and Eddie could hang with these dudes. The guys are all in their 30s, none have steady gainful employment, all live with their parents. Two of them are a team of songwriters who not only don’t get their songs published, but don’t even make the effort. One is a former baseball player who never quite made the bigs. I’ll let Goodis describe the fourth guy:

Dippy was thirty-three years old. One or two or three days a month he helped somebody install oil burners and made himself a few dollars. He was short and thin and he rolled his own cigarettes and plastered his black hair down with a lot of grease. He seldom bathed.

These four spend an awful lot of their (plentiful) free time standing on a street corner, chewing Indian Nuts they get out of a penny machine as they watch the world go by. Sometimes they talk about how nice it would be to move to Florida, sometimes about how pointless it is to try and find work. They attempt to make dates for themselves by making phone calls to random women whose numbers they find in the phone book, pretending to be long-lost friends of the women, and saying they want to have a party with them and their female friends. Every once in a while a couple of girls, who are as bored as the fellas are, bite.

If I’m making it sound like TBOTSC is a comical novel, I have misled you. There are amusing moments, sure, but overall the story is about as bleak as it gets. And it’s savage. Nobody in the Depression-era tale has any money, few have work or prospects, but many of them have pent up anger and violence inside their bitter selves. The fistfights that occur between the book’s pages—including one between a woman (the “Blonde” of the title) and her mother-in-law, and another between one of the guys and his abusive boss at a temporary job packing boxes for a department store around Christmas time—are so vividly described that you feel each punch, kick, face scratch, crotch grab, and head-butt, like somebody just did all that harm to you.

I also wasn’t completely honest with you in the opening here, when I suggested that nothing happens to anybody in the story. Well, I halfway lied. Things do happen to Ralph Creel, one of the four street corner bums and the ultimate focus of the story. Ralph is 30 and he lives with his parents and two sisters. He is the lyricist from the songwriting team. Ralph is a quiet guy who likes to read about boxers and likes to sleep in until noon. He’s an unassuming sort (well, I guess he would be, wouldn’t he?) yet one who has seething rage in him, that comes out over some of novel’s (few) dramatic moments.

What happens to Ralph, mostly, is that two women come into his life at the same time. One is a nice girl, whom he meets at one of those parties his buddies organize via their telephone ruse. This girl, Edna, is like a lot of people in the story—she spends her days walking up and down Market Street, hoping to find some kind of a job. Her dad’s out of work and soon her family won’t be able to pay their rent. She takes a shine to the shy Ralph at the party, and when he shows up at her house, by himself, soon after, she is thrilled. We don’t get to know Edna all that well, but from what we see she appears to be a good soul, someone a guy like Ralph might be smart to marry. And she’s into Ralph, despite the fact that he tells her:

I don’t work hard because—well, I just don’t like to work hard. I’m a bum.

Edna is convinced that Ralph and his partner could make something of themselves, if they would get ambitious and try to market their songs, and she appears ready to be the loving woman who spurs Ralph into some activity. But Ralph is wary, of Edna and of the feelings she inspires in him.

The other woman in Ralph’s life is Lenore, the “Blonde.” Lenore, 36, couldn’t be more different from Edna. Where Edna is salt of the earth, Lenore, who is the sister-in-law of Dippy from Ralph’s crowd, is a peroxide job who has a loud mouth, ill manners, a vicious temper, and an overall frowsy yet provocatively sexy aura. She gets into catfights with her mother-in-law, fattens herself up on candy and thick sandwiches while others around her starve, and she uses and abuses hapless guys. Here, let’s let Goodis tell us how Lenore handles the plentiful menfolk from her riotously adulterous life. Keep in mind that the woman lives with her husband’s extended family:

The Italian was a construction foreman. He was rough. Lenore liked him. She liked his hands. Sometimes he got a bit too rough, but Lenore knew how to manage that. She knew how to manage him and all the rest of them. She had something on each and every one of them. All they had to do was open their mouths just once and she would give them away. They all knew that. Lenore always made sure she had something on a man before she added him to her list. The Italian, for instance. The Italian wanted to get his wife back. His wife was a pretty little Italian girl who lived with the two kids and the grandmother in South Philly. Lenore knew the address. She told the Italian if he ever tried to pull any monkey business, she would go down to South Philly and open her mouth. The Italian would never get his wife back. Whenever Lenore yelled this at him, the big, rock-like Italian would start to cry. Lenore would laugh at him. She laughed at all of them.

Charmed? Neither is Ralph, and when Lenore makes a come-on to him in the beginning of the story, he tells her to take a walk. But Lenore sees something in his eyes that tells her Ralph doesn’t really want her to go away from him. She also senses the tiger that resides inside Ralph’s quiet shell, and she wants her some of that.

So this is what happens to Ralph. Within his do-nothing life are two girls who want him. And it’s the classic story of him having to choose between the

“good girl” and the “bad girl,” just as in another standout noir novel, Charles Williams’s The Hot Spot.

The Blonde on the Street Corner is not David Goodis’s best-known novel. That might be Dark Passage, which was made into the Bogart/Bacall film of the same title and that almost brought the doomed Goodis fame and fortune. Or it could be Down There, which Francois Truffaut used as the basis of his French New Wave classic film Shoot the Piano Player. I’m not going to attest that TBOTSC is better than those two, or others of Goodis’s (Cassidy’s Girl is a particular favorite of mine). But I’ve covered TBOTSC here because it is a brilliantly written work of noir fiction that is more lost than those other titles of Goodis’s. It’s a novel that’s filled with the grittiest realism possible, yet is also dreamlike. It’s both mercilessly ennui-laden, yet mesmerizingly lyrical. And nobody but David Goodis could have written this book.

Let’s close with a scene in which Ralph faces one of the great challenges of his life: he’s trying to get out of bed. Well, not trying all that hard:

Ralph opened his eyes and looked at the window. He saw the grey and cold sky and the slush sliding down the glass. He banged his head into the pillow and rolled over. He was tired. He was cold. His toes were freezing. He peered over the edge of the patch quilt. His toes were outside the quilt. He pulled his toes inside. He yawned and rolled over again. He wondered what time it was. He had to take a leak. But he didn’t want to get out of bed. It was too cold. He was too tired. But he had to get out of bed. He cursed a few times and then he counted to five, figuring that on five he would jump out of bed and run to the bathroom and be back in bed before he was fully awake. But at five he was too yellow to get out of bed. He tried again, this time counting to three. Again he stayed in bed. His next try was fifteen, and this time he leaped out of bed and raced to the bathroom and came running back and took a dive into the bed, crawled under the quilt and told himself he was going to stay in bed all day. He wondered why he was so tired. He wondered what time it was. He remembered that he had slept badly. He had been dreaming. What had he been dreaming about? Why wasn’t this quilt warmer? A quilt should be warm. This room was an iceberg. Again he looked up and over the edge of the quilt and saw the opened window. The window ought to be closed now. No wonder it was so cold. The window was wide open. It ought to be closed. How long it would take him to leap out of bed and close the window and get back in bed and fall asleep again? He counted to five. No go. He counted to fifteen. He told himself he wasn’t going to get out of bed again, window or no window. He rolled over and wrapped the quilt about him.

Brian Greene writes short stories, personal essays, and various things about books, music, and film. His articles on crime fiction books and authors have also been published by Noir Originals, Crime Time, Crimeculture, Paperback Parade, and Mulholland Books. He lives in Durham, North Carolina, with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, their cat Rita Lee, and too many books and CDs.

Terrific post. Thanks for the introduction to David Goodis, who has a very cool name for a writer of noir.

I enjoyed that, thanks’! This stuff needs to be reprinted.