At the heart of every mystery story—at the heart of every criminal plot—there is a central deception. It may involve the means by which the crime was committed, or the method of escape, or the nature of the motive, or the identity of the perpetrator. Or all of these, with ample misdirection to avoid detection.

At the heart of every mystery story—at the heart of every criminal plot—there is a central deception. It may involve the means by which the crime was committed, or the method of escape, or the nature of the motive, or the identity of the perpetrator. Or all of these, with ample misdirection to avoid detection.

These lies tend to beget others, wrapping plot and characters in successive layers of falsehood. This is the onion that the detective must peel in order to bring the central criminal secret to light and expose the hidden truth.

This is the essential action of thousands of mystery novels, absorbing millions of readers around the world.

Why does this process of deception and discovery endlessly fascinate us?

Several possible reasons occur to me, but I think the main reason involves the strange and powerful position that deception itself occupies in human nature.

To begin with, consider the conflicts that are inherent in lying. We hate liars, yet none of us is completely truthful. We view mendacity in others as a serious fault, a moral failing, a despicable behavior; yet it is a fundamental survival strategy deeply ingrained in us by evolution. Children lie and engage in sophisticated manipulation, it would seem, almost from the moment they are capable of distinguishing between themselves and other people.

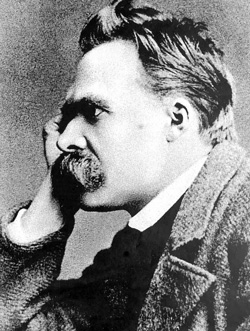

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche observed that the ability to deceive, to create a misleading impression, was probably the chief survival advantage conferred by rationality, since it provided a way of defeating brute force. The Greek hero Odysseus was celebrated for his duplicity, the quality that saved his life more than once and made it possible for him to live happily ever after with his faithful Penelope.

And we start early. I’m reminded of a recent situation involving a three-year-old girl I know, an absolutely charming little person. She was taken by her grandmother to the zoo—a place she loves to visit. As soon as they arrived, she insisted, as always, on visiting her favorite animal first. Her observant grandmother noted, however, that on these visits the little girl typically paid very little actual attention to her so-called “favorite” animal, and that the real attraction seemed to be something else entirely.

The particular animal’s location just happened to be next to one of the zoo’s ice cream stands. After milling around for a minute or so in front of the animal’s enclosure, the three-year-old would invariably “notice” the nearby stand and ask her grandmother to buy her a cone. Which her grandmother would do.

But that small manipulation is not the end of the story. That night, after they returned to the parents’ house, and after they’d all had dinner together, the three-year-old asked her mother if she could have ice cream for dessert. Since there was a rule that she could only have ice cream once a day, her mother asked her if she’d already had ice cream at the zoo.

There’s more to the story, but it adds nothing to the key point. And for me the key point is that it’s not a particularly unusual story.

We’re human.

We lie.

Some people believe that we’re hard-wired for honesty and learn deception as we mature. Other people, myself among them, believe we’re hard-wired for deception (since it has more immediate survival value) and learn the value of honesty later. If I ever write a serious academic essay on the subject, I have a catchy title ready: Natural Born Liars.

But it’s not likely that I’ll ever write an academic essay on that subject. Because I already have the opportunity to deal with the theme of duplicity in the greatest medium ever developed for such an exploration—the mystery-thriller. In my opinion, this is the form that’s tailor-made for examining that “tangled web we weave when first we practice to deceive.”

The mystery-thriller typically begins with a false facade—concealing motives and machinations and identities—and the action of detection then proceeds through a gradual, rational process of exposure. In the stories I like best, not only is the underlying criminal secret unraveled, but its root causes and emotional consequences are laid bare.

The mystery-thriller is a form that will always be with us. Because again and again it holds up to the light this core element of our lives—this strategic tool of human nature, this tragic human flaw.

Deception.

The double-edged sword we employ at our own peril. The fascinating heart of the genre.

As far back as he can remember, John Verdon wanted to be someone else. After working as a stunt man, he devoted himself to martial arts, motorcycles, and sports cars, even woodworking and getting his commercial pilot’s license. After his wife left her teaching job in NYC, they moved to the Catskills where she encouraged him to write the novel he’d always wanted to write. That became the first puzzling thriller featuring Dave Gurney, Think of a Number, followed by Shut Your Eyes Tight and now Let the Devil Sleep. Join him at his new Facebook author page.