Action without the ballast of character lacks meaning or purpose in fiction, just as it does in life. So, in direct defiance of the current craze for action-packed thrillers, of which I am admittedly a participant, I say: Slow down! Make it matter. If you aim to write genuine nerve-prickling suspense, you must do more than entertain: you must cajole, convince, seduce, trick, and sometimes devastate your reader.

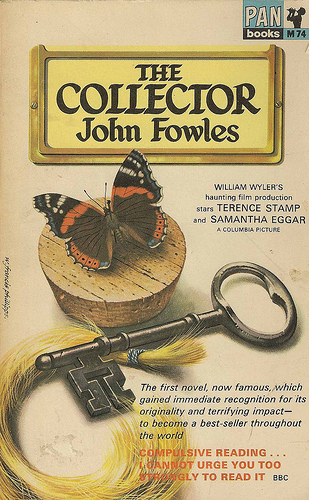

Frederick Clegg abducts art student Miranda Grey and holds her in his basement while managing to convince himself that he is not ultimately responsible for her gradual disintegration. Most of the novel is a first-person narrative by Clegg in which we’re introduced to his uniquely skewed vision of Miranda and how she must, and will, be subsumed into his world. We watch as his crush evolves into a set of preparations, as fascination becomes an imperative. By the invulnerable standards of his obsessive inner discourse, Clegg convinces himself, and almost convinces us, of the inevitability of his plan to snatch the unsuspecting Miranda off the street just as he would capture a butterfly for his collection. Gradually, we come to understand how this makes perfect sense to him, even if it is patently insane. But what makes the narrative so riveting is not just our dawning understanding of the magnitude of what is about to happen, but Clegg’s prosaic approach to it; it’s as if he’s plodding through errands mapped by a shopping list that started small and reasonable, and then turned dangerously elaborate. By the time we get to Miranda’s first-person narrative, a shorter section late in the novel, we’re so consumed by Clegg’s thinking that transitioning to hers feels uncomfortable as we’re jolted back into what we normally think of as reality.

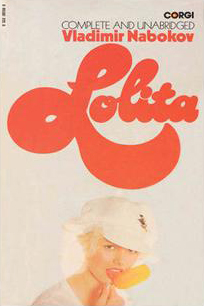

Another example of a uniquely terrifying literary psychopath is, of course, Vladimir Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert, whose singular quest to sexually possess a child drives Lolita. It’s decidedly not a love story, yet by virtue of his brilliant writing and expert character development, Nabokov managed to convince a generation of critics that Humbert’s abduction of Lolita is somehow a romance, just as Clegg convinces himself that his abduction of Miranda is a romance. But we won’t delve too deeply here into the eerie thought processes of Humbert Humbert, that conniving predatory pedophile. Suffice it to say that what he and Clegg shared was a storyteller ready, willing and able to delve so deeply into his protagonist’s mind and life that character becomes action: you feel the trapped terror of the victim, you can’t stop turning pages and you’ve never felt so creeped out, even by the newspaper.

Another example of a uniquely terrifying literary psychopath is, of course, Vladimir Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert, whose singular quest to sexually possess a child drives Lolita. It’s decidedly not a love story, yet by virtue of his brilliant writing and expert character development, Nabokov managed to convince a generation of critics that Humbert’s abduction of Lolita is somehow a romance, just as Clegg convinces himself that his abduction of Miranda is a romance. But we won’t delve too deeply here into the eerie thought processes of Humbert Humbert, that conniving predatory pedophile. Suffice it to say that what he and Clegg shared was a storyteller ready, willing and able to delve so deeply into his protagonist’s mind and life that character becomes action: you feel the trapped terror of the victim, you can’t stop turning pages and you’ve never felt so creeped out, even by the newspaper.

At this point, you’re saying, “Aha! But that’s psychological suspense.” To which I respond: No, it’s suspense. Suspense is character. Without character, action is summary, and summary is boring. (So is slicing up all our fiction into little sub genres, adding to the disjointedness of an already hard-to-navigate marketplace.)

If that little red devil really wants the thriller market to rock ‘n roll, bring on the great, creepy, spine-chilling characters who make it matter. Dinner with Hannibal Lecter, anyone?

Katia Lief is author of thrillers, including Next Time You See Me and You Are Next. She also teaches fiction writing at the New School in Manhattan.

I remember reading The Collector and then seeing the movie, and it was absolutely chilling. Still is.

Thnaks for Shaering it