Lanie Price, a 1920s Harlem society columnist, witnesses the brutal nightclub kidnapping of the “Black Orchid,” a sultry, seductive singer with a mysterious past. When hours pass without a word from the kidnapper, puzzlement grows as to his motive. After a gruesome package arrives at Price's doorstep, the questions change. Just what does the kidnapper want—and how many people is he willing to kill to get it?

Evil hides behind the genteel faades of affluent Strivers' Row and stalks the ballroom of one of Harlem's most famous gay parties. In a complex plot that keeps the reader tied to the page, Black Orchid Blues explores the depths of human depravity and the desperation of its victims.

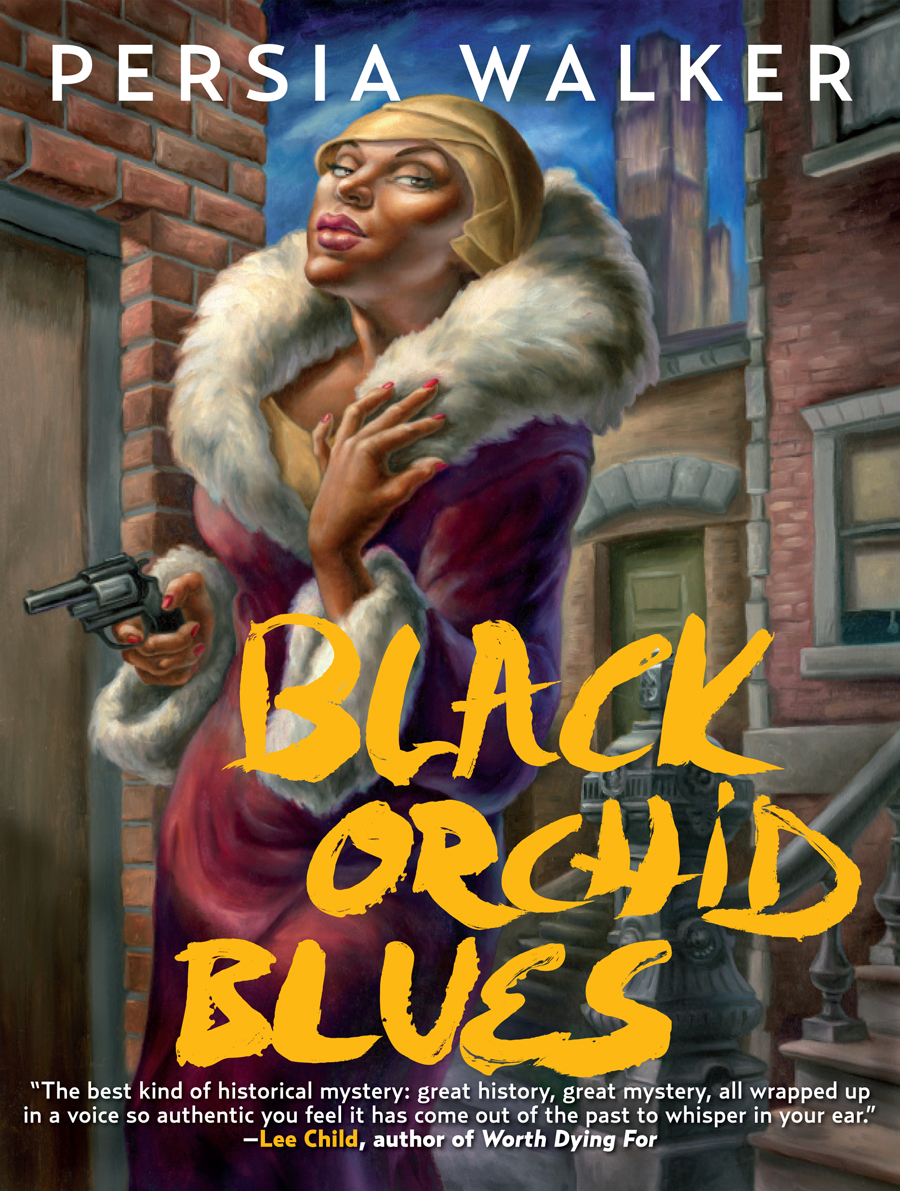

An exclusive extended excerpt of Chapters 1-5 of Black Orchid Blues by Persia Walker published by Akashic Books.

Chapter 1

Folks used to talk about her gravely voice, her bawdy banter, and how she could make up new, sexy lyrics on the spot. Queenie captured you. She got inside your mind, claimed her spot, and refused to give it up. Once you heard her sing a song, you’d always remember her performance. No matter who was singing it, Queenie’s voice would come to mind.

Sure, she was moody and volatile. And yes, whatever she was feeling, she made sure you were feeling too. But that was good. That’s what could’ve made her great—could’ve being the operative word.

I first met Queenie at a movie premiere at the Renaissance Ballroom, over on West 138th Street. The movie I’d soon forget—it was some ill-conceived melodrama—but Queenie I would always remember.

It was a cold day in early February, with patches of dirty ice on the ground and leaden skies overhead. It was late afternoon, an odd time for a premiere, so the event drew few fans and, except for Queenie, mostly B-level talent.

It was a party of gray pigeons and Queenie stood out like a peacock. For a moment, I wondered why she was even there. She was vivid. She was vibrant. And when she found out that I was Lanie Price, the Lanie Price,the society columnist, she went from frosty to friendly and started pestering me to see her perform.

“I’m at the Cinnamon Club. You must’ve heard of me.”

Well, I had, actually. Queenie’s name was on a lot of lips and I’d heard some interesting things about her. I could see for myself that she was bold and bodacious. I decided on the spot that I liked her, but I couldn’t resist having a little fun with her, so I shrugged and agreed that, yeah, I’d heard of . . . the Cinnamon Club.

Queenie caught the shift in emphasis and was none too pleased. She raised her chin like miffed royalty, pointed one coral-tipped fingernail at my nose, and, in her most regal voice, said, “You will appear.”

I smiled and said I’d think about it.

The fact was I had a full schedule. A lot of parties were going on those days, and it was my job to cover the best of them. However, I finally did find time to stop and see Queenie a couple of weeks later. I called in advance and Queenie said she’d make sure I had a good table, which she did. It was excellent, in fact, right up front.

To the cynic, the Cinnamon Club was little more than a speakeasy dressed up as a supper club, but it was one of Harlem’s most popular nightspots. It was on West 133rd Street, between Seventh and Lenox Avenues, what the white folks called “Jungle Alley.” That stretch was packed with clubs and given to violence. Only a few weeks earlier, two cops had gotten into a drunken brawl right outside the Cinnamon Club. One black, one white—they’d pulled out their pistols and shot each other.

That was the neighborhood.

As for the club itself, it was small but plush. The lighting was dim, the chairs cushioned, and the tables round and tiny and set for two. All in all, the Cinnamon Club seemed luxurious as well as intimate.

It was packed every night and most of the comers were high hats, folks from downtown who came uptown to shake it out. They liked the place because it was classy, smoky, and dark. For once, they could misbehave in the shadows and let someone else posture in the light. That someone else was Queenie. The place had only one spotlight and it always shone on her.

Rumor had it that she was out of Chicago. But back at that movie premiere, she’d mentioned St. Louis. All anybody really knew was that she’d appeared out of nowhere. That was late last summer. It was midwinter now and she had developed a following.

You had to give it to her: Queenie Lovetree commanded that stage the moment she stepped foot on it. Every soul in the place turned toward her and stayed that way, flat-out mesmerized and a bit intimidated too. Only a fool would risk Queenie’s ire by talking when she had the mic.

A six-piece orchestra, one that included jazz violinist Max Bearden and cornetist Joe Mascarpone, backed her up. Her musicians were good—you had to be to play with Queenie—but not too good. She shared center stage with no one.

At six-foot-three, Queenie Lovetree was the tallest badass chanteuse most folks had ever seen. She had a toughness about her, a ferocity that kept fools in check. And yes, she was beautiful. She billed herself as the “Black Orchid.” The name fit. She was powerful, mythic, and rare.

Men were going crazy over her. They showered her with jewels and furs and offered to buy her cars or take her on cruises. In all the madness, many seemed to forget or stubbornly chose to ignore a most salient fact, the one secret that her beauty, no matter how artful, failed to hide: that Queenie Lovetree wasn’t a woman at all, but a man in drag.

When Queenie appeared on stage, sheathed in one of his tight, glittering gowns, he presented a near-perfect illusion of femininity. He could swish better than Mae West. His smile was dirtier, his curves firmer, and his repartee deadlier than a switchblade. From head to toe, he was a vision of feminine pulchritude that gave many a man an itch he ached to scratch.

That night, Queenie wore a dress with a slit that went high on his right thigh. Folks said he packed a pistol between his legs, the .22-caliber kind. If so, you couldn’t see it. You couldn’t see a thing. Queenie kept his weapons tucked away tight.

Gun or no gun, he smoked. When he took that mic, the folks hushed up and Queenie launched into some of the most down and dirty blues I’d ever heard. He preached all right, signifying for everything he was worth, and that crowd of mostly rich white folk, they ate it up.

During the set, Lucien Fawkes, the club’s owner, stopped by my table. He was a short, wiry Parisian, with hound-dog eyes, thin lips, and deep creases that lined his cheeks.

“Always good to see you, Lanie. You enjoying the show?”

“I’m enjoying it just fine.”

“I’ll tell the boys: anything you want, you get.”

After Queenie finished his set, the offers and invitations to join tables poured in. He took exuberant pleasure in accepting them, going from table to table. But that night, they weren’t his priority. He air-kissed a few cheeks, exchanged a few greetings, and then slunk over to join me.

“The suckers love me,” he said. “What about you?”

“I’m not a sucker.”

“Well, I know that, Slim. That’s why you’re having drinks on the house and they’re not.”

He sat down and turned to the serious business of wooing a reporter.

“So, what do you think? Am I fantastic or am I fantastic?”

“I’d say you’ve got a good thing going.”

“You make it sound like I’m running a scam.”

I hadn’t meant it that way, but given his fake hair, fake eyelashes, and fake bosom, I could see why he thought I had. “I’m just saying you’re perfect for this place and it’s perfect for you. Everybody’s happy.”

“It’s okay,” he said. “For now.”

“You have plans for bigger and better things?”

“What if I do? There’s nothing wrong with that.”

“Not a thing. I’ve always admired ambitious, hard-working people.”

“Honey, I ain’t nothing if not that.” He leaned in toward me. “People say you’re the one to know. That you are the one to get close to if somebody’s interested in breaking out, climbing up. Because of that column of yours. What’s it called?”

“‘Lanie’s World.’”

“That’s right. ‘Lanie’s World.’” He savored the words. “And you write for the Harlem Chronicle?”

“Mm-hmm.”

“You think you can write a nice piece on me?”

“Well,” I hesitated. “There issome small amount of interest in you, but—”

“Small? People are crazy about me. The letters I get, the questions. They want to know all about me. Where I come from, what I like, what I don’t, what I eat before going to bed.”

I shrugged. “But they’ve heard so many different stories that—”

“I promise to tell you the whole truth and nothing but.”

“Well, thanks.”

I’d been in the journalism game for more than ten years. I’d worked as a crime reporter, interviewing victims and thugs, cops and dirty judges. Then I’d moved to society reporting, where I wrote about cotillions and teas, parties and premieres. It seemed like a different crowd, but the one constant was the mendacity. People lied. Sometimes for no apparent reason, they obfuscated, omitted, or outright obliterated the truth. And often the first sign of an intention to lie was an unsolicited promise to tell the truth, “the whole truth and nothing but.”

In some areas, of course, I was sure Queenie would be factual, but in others . . . it didn’t matter. I’d decided to interview him. I was sure to get a good column out of him. I just wasn’t sure this was the place to do it.

People kept stopping by. They shook his hand and praised him and begged him to join them. Men sent drinks. They sent flowers and suggestive notes. But they were out of luck that night. After every set, he’d rejoin me, tell me a little bit here, a little bit there.

“I like action,” he said, “lots of action, diamond studs and rhinestone heels. I love caviar and chocolate, sequins and velvet. Most times, I’m a lady. But I can smoke like an engine and cuss like a sailor. The men love me cause I treat them all the same. I call them all Bill. By the way, you got a ciggy?”

I shook my head. “Never took to ’em.”

He turned and tapped a man sitting at the next table. “Butt me, baby.”

“Sure,” the guy said, grinning. He produced a cigarette and lit it.

Queenie flashed a dazzling smile, said in a husky voice, “Thanks, Bill,” then turned his back before the fellow could make a play.

“Bill” shot me a rueful look. All I could do was give him a sympathetic smile.

During one of the longer set breaks, Queenie invited me back to his dressing room, “so we can talk without them fools interrupting.” He described how at age fourteen he’d fallen in love with a sailor who smuggled him to Ankara.

“He was the greatest love of my life, but that bastard sold me.”

“Sold you?”

“Yeah. To a guy in a bar.” He saw my expression and added, “But seriously, I’m not lying. And that guy turned around and sold me again—to a sultan for his harem.”

Believable or not, Queenie’s tales were certainly fascinating.

He described corrupting wealth and murderous intrigues. Sultan’s wives were poisoning each other and one another’s children in a never-ending struggle for power.

“For a while there, it was touch and go. I didn’t eat or drink nothing without my taster.”

“How terrible,” I said, with appropriate horror and sympathy.

At the next break, he talked about his further adventures in Europe. When he was nineteen, he said, the sultan sent him off to an elite finishing school near Lake Geneva, in Switzerland.

“Honey, I couldn’t take that place. I made tracks the minute they weren’t looking. Went to Paris. Got me a nice hookup. Performed at the Moulin Rouge. Would’ve stayed there too, but a rich uncle came and found me.”

“A rich uncle?”

“Mm-hmm,” he said, with a perfectly straight face. “He’s dead now. But that’s okay, cause now I’ve got lots of rich uncles.” He gave a wicked wink. “A girl can’t have too many, you know.”

I just had to shake my head. At my expression, Queenie threw his head back and laughed. His shoulders rocked with deep, raunchy amusement. He laughed so hard, tears rolled down his cheeks.

“Oh shit,” he said, trying to regain control of himself, “I’m ruining my makeup.”

I’ve seen and heard enough to be fairly immune to what shocks most people. So it wasn’t Queenie’s stories that got me. It was the obvious pride and conviction with which he told them. People talk about being larger than life, but it usually doesn’t mean a thing. When applied to Queenie, it did. And his tales were as tall as tales can get. Sure, they were hokum. That was obvious, but it was okay. It was more than okay because it would make rip-roaringly good copy.

Back in the clubroom, watching him onstage, I mused about his real history. No doubt it was like hundreds of others. He’d been a touring vaudevillian, or had grown up singing gospel in some church down South, then either ran away from home or was kicked out. He was a young boy with a pretty face, the kind that would attract certain types of men. Boys like that, out on their own, they lose their innocence fast. Queenie was no exception.

No doubt he’d spent years on the circuit, in smaller clubs, dark and dirty. Underworld characters had smoothed his path and a wealthy man or two had taught him to love the finer things in life—men who lived double lives, with women during the day and men at night. Now Queenie was here in New York, the big time. It was his chance, and he was going to run with it, milk it for all it was worth. I certainly couldn’t blame him.

Queenie liked to flash a big diamond ring. When he sang, the ring caught the light. It was a lovely yellow diamond, set in yellow gold, surrounded by small white diamonds. I had a good eye for jewelry, but at that distance I couldn’t say whether it was fake. If it was real, then it was worth ten times a poor man’s salary. If it wasn’t, then it was a darn good imitation—and even imitations like that cost a pretty penny.

“That got a history?” I asked when he rejoined me.

He glanced at the ring, smiled. “Honey, everything about me has a history.”

“Care to tell me this one?”

He fluttered his large hand and held up the ring for a long, loving look. Then he smiled. His golden eyes were feline. His husky voice just about purred. “Not this time, sugar. But I will, if you do a good piece on me. If you do it right, then I’ll give you exclusive access to Queenie Lovetree. You’ll be my one and only and I won’t share my shit with anyone but y—”

Gunfire exploded behind us. I jumped and Queenie’s eyes widened. Heads swiveled and the music shredded to a discordant halt. Then someone gasped, another screamed, and people nearby started diving under tables.

At first, I wondered why.

But as people scrambled to get out of the way, I could see the club’s bouncer, a man named Charlie Spooner, and the coatcheck girl, Sissy Ralston, emerging unsteadily from the area of the entrance. They wound their way past the tables, coming toward us, hands held high. Directly behind them, a man emerged from the shadows. He wore a Stetson, a big black one, pulled down low to cover his eyes, and a long, black trench coat with a turned-up collar.

It was a very sexy look, but the true eye-catcher was the tommy gun he held on his hip, his black-gloved hands firmly grasping the two pistol grips. It looked real, it looked deadly, and he had the business end of it pressed against Spooner’s spine.

The bouncer was a good guy, a decorated veteran of the 19th Infantry. He was married, with a kid on the way. He’d been on the job six months, had taken it, he told me, because he could find nothing else. Now his olive-toned skin had turned ashen gray; his usually jovial face was tight with fear. He had survived bombs and missiles and landmines overseas. Had he gone through all that simply to die in a stupid nightclub robbery at home?

I knew the Ralston girl too. That child couldn’t have been more than sixteen. She was just a kid trying to earn money for her family. Her father had died the year before and her mother was a drinker. Sissy was the sole support for her seven-year-old brother and six-year-old sister.

There they were, the bouncer and the coatcheck girl, so terrified they could barely put one foot in front of the other.

Death march. I flashed on stories my late husband had told me about the war, stories of soldiers and civilians marched to their execution, of whole villages lined up against a wall and shot. A chill went through me. I tried to think, tried to restrain the fear and think.

A million questions raced through my mind.

Was this the result of some bootleggers’ war? Or was it supposed to be a robbery? If so, would he take the money and run? Or was he the type to kill us all just for the hell of it?

He was covered. That meant he wanted to make sure no one could identify him. Did that mean that if no one did anything stupid, just gave up the jewels and wallets and fancy timepieces, he’d let us all live to tell the story?

I glanced across the crowded room, at the white faces peering out of the smoky gloom, and didn’t see a hero among them, thank God.

The gunman shoved Spooner and Ralston to the small open space just before the stage and had them stand side-by-side.

“Everybody, wake up!” he yelled. “Take your seats and show your hands.”

But we were all too scared to move.

“I will count to three and then start shooting—for real. One . . . two . . .”

My heartbeat was pounding a hot ninety miles a minute, but my hands and feet felt cold. From the corner of my eye, I glimpsed Queenie slipping his right hand under the table. The gunman saw it too. He swung around and leveled his weapon on us.

“Bring it out,” he said. “Nice and slow.”

Queenie gave him an insolent look and mouthed the word No.

I was stunned. I’d talked to Queenie long enough to know he thought he could handle anyone and anything, but what the hell was he thinking? Okay, so he had pride. He didn’t want people to see that he was scared. But this was not the time to act all biggety and try to impress people. He could get us killed.

“Queenie,” I hissed, “do as he says.”

“No.”

The gunman’s lips twitched, but he said nothing. He looked Queenie in the eyes, made a slight adjustment in his aim, and squeezed the trigger.

Copper-jacketed pistol rounds erupted from the muzzle in a sheet of flame; a shower of shiny brass cases rained down from the breech. The bullets found Spooner and ripped a trench in his chest. Blood splattered everywhere. The Ralston kid crumpled in a dead faint. People shrieked. Some ducked down again, but others raced for the door. They were screaming, tearing at each other.

“Shut up and get back here!” the gunman swung around and yelled. “Shut up or I’ll mow you down!”

The bouncer pawed at his ravaged chest. He plastered his big hands over his gaping wounds, as if he could hold in the blood. Then he looked up at me, in mute sadness. He stumbled forward a step and his heart gave out. He sagged to his knees and fell, facedown.

The gunman stared at the dead man before pointing an accusing finger at Queenie. “You!” he said. “You made me do that!”

Queenie had gone gray under his elaborate makeup, ashen and speechless. He finally understood. This was not one of his tall tales, where he could play the star. This was real.

“Back to your seats everybody!” the gunman yelled. “Get back in your seats and show your hands. Do it, or I’ll start shooting. And I won’t stop till the job’s done.”

This time, folks moved. They scrambled to get back in place.

The killer turned to Queenie and me. “Come over here, the both of you, where I can see you.”

We stood up and edged around the table, keeping our distance from him.

The gunman was taller than me, but not by much, which made him short for a man. The coat seemed to have padded shoulders, but I had the feeling that he would’ve appeared broad even without them, that he was built like a quarterback, muscular and stocky.

For the most part, he’d successfully concealed his face, but some of it showed above the mask. His eyes had a distinctive almond shape and they were light-colored: blue or gray, I couldn’t be sure. And the band of skin showing over the bridge of his nose, it was light too. In other words, this was a white guy. Last, but not least, I detected an accent. European, northern European, perhaps. So, not just any white guy, but a Europeanwhite guy. He’d sure traveled a long way to cause trouble.

“Now, you,” he told Queenie, “take the heater out or she’s next.” He pointed the gun at me.

I half-turned to Queenie to see what he’d do. Please, don’t do anything stupid.

Queenie slipped his hand through the slit of his dress. And lingered there. He was going to try something dumb, like shoot from down there. I could see it in his eyes.

Don’t do it. Don’t do it.

Queenie looked at me and I looked at him. If he pulled a stunt like that and I managed to survive, then I was going to kill him myself. That’s what I was thinking and that’s what I put in my eyes.

I guess he got the message.

He eased out a small black handgun and aimed it downward. My lungs expanded and I inhaled big gobs of sweet relief.

“Put it on the floor and kick it over here,” the gunman said.

Queenie did as told. He kept his eyes on the submachine gun the whole time. I still didn’t trust Queenie not to try something and I guess Mr. Tommy Gun didn’t either, so I understood why he was keeping his weapon trained, but I wondered why it was trained on me.

“Get over here.” The gunman indicated the space right in front of him.

Queenie glanced at me. His eyes held doubt, fear, and resentment.

“Do what he says,” I whispered. “Please. Just do it.”

“Come on,” the gunman growled.

Queenie’s gaze returned to the gunman. Stone-faced, he held up his gown, then stepped delicately and ladylike over Spooner’s body. He stood before the gunman, chest heaving, eyes narrowed, and said with tremulous bravado, “Well?”

The gunman slapped him. He was a full head shorter than Queenie, but wide and solid. Queenie swayed under the blow but didn’t stumble. He seemed more stunned than anything. His hand went to his lip and came back bloodied. His jaw dropped in alarm.

“My face! You piece of shit! You hurt my face!”

The gunman slapped him again. This time Queenie went down. He tripped backward over Spooner and landed on the floor in a pool of blood. He scrambled away from the body with a horrified cry, and got to his feet. His hands and dress were smeared red. From the expression on his face, all resistance had finally been knocked out of him.

The gunman gave me a nod. “You! Come here.”

Queenie and I exchanged another glance. Then I took a step forward. The gunman produced handcuffs from his pocket and tossed them at me. I caught them instinctively.

“Cuff up the songbird,” he said. “You,” he told Queenie, “hands behind your back.”

If there was one thing I’d always told myself I would never do, it was to be an accomplice to a crime. I had read, and written, so many stories in which victims had cooperated with their killers. They had done so in the minute hope of surviving, but all they had really done was make it easier for their killer to get them alone, isolate them and do what he felt needed doing.

I’d always said I would resist. I wouldn’t make it easy. Oh no. Not me.

But now here I was and things appeared differently. They weren’t so cut and dry. Someone else’s life was at stake, not just mine.

I could refuse or cooperate. If I refused, then he’d probably shoot me and cuff Queenie himself—or worse, shoot someone else. If I went along and bided my time, there was some hope I’d survive and that everyone else would too.

Everyone, but maybe not Queenie.

“Well,” the gunman said, “who should I shoot next?” He glanced down at the Ralston girl, still unconscious on the floor. “How about her?” He turned his gun, took aim.

“No!” I pulled Queenie’s hands behind his back and slipped on the handcuffs.

He flinched at the touch of cold metal. “Please, no, Slim. You—”

“It’ll be all right,” I said, trying hard to sound calm.

I snapped the cuffs shut, and when the gunman ordered me to step back, I did.

He made Queenie stand next to him and checked the cuffs. “Good.” Then he grabbed Queenie and started backing out. He slinked to the rear exit, backstage left, and kept the singer in front as a shield.

Queenie panicked. “Oh come on now, people! Y’all ain’t gonna let him take me like this, are you? Somebody do something. Please!”

People stayed frozen to their seats. No one was willing to play the hero. Not in the face of that weapon.

Queenie’s eyes met mine. “You! Slim, you—!”

The whine of police sirens rang through the air. The cops were probably headed to another emergency, but the killer assumed the worst. He pushed Queenie aside and sprayed the room with gunfire. All hell broke loose. People stampeded toward the door. Wall sconces exploded. The room fell dark. Plaster and dust showered down.

I heard screams. I heard cries. I dove under a table and covered my head. Bullets ripped up the floor two inches from my face. I couldn’t believe they didn’t touch me.

“Motherfucker! Get your hands off me!” Queenie cried.

I heard the back door bang open. I heard a scuffle and a scream. Then the door slammed shut and all I heard was the heavy thumping of my terrified heart.

Chapter 2

Despite the shadows, I could detail the destruction. The bullets had torn open bodies as well as furniture. Four people lay sprawled over their tables or slumped in their booths. Blood and shattered glass covered everything. The air was thick with gun smoke.

Now others emerged from their hiding places. Stunned patrons staggered to their feet. The musicians, who had flattened themselves on the floor, slowly straightened up. The sirens drew nearer.

I couldn’t risk being found here. If I were spotted, I’d end up at the police station instead of the newsroom, where I needed to be, writing my story.

It was colder than a mother-in-law’s kiss outside. I was wearing a thin black cocktail dress with lace at the shoulders and hemline. Sexy as all get- out, but no protection against the cold. I needed my hat and coat, but they were at the check-in. I couldn’t risk going back over there.

I felt around for my purse, found it on the seat, and made for the back exit. I pushed open the door and gasped at the sudden rush of frosty air. I stumbled outside, shivering, and took a moment to get my bearings. It was well after midnight and the only light came from the stars above. The city landscape seemed foreign, filled with shadows I could barely identify. Garbage, milk crates.

If Queenie’s body had been at my feet, I would’ve stumbled over it before I saw it.

Pressing myself against the side of the building, I moved swiftly toward the street. Snow and ice blanketed the ground. The wind pierced me to the bone and I shivered from head to toe. I could hear the rumble of curious and confused voices. I could see the flashing beams of a patrol car. I made it to the corner, ducked down, and peeped around the edge.

The first cop car screeched to a halt in front of the buildings. So those sirens hadbeen for us. Who called the coppers? Maybe one of the waiters.

A crowd had gathered and the folks who’d been on the inside were starting to stumble out. The bulls pushed their way through and seconds later ran back out. Soon, there would be more cops and then detectives and they would have questions.

My car was parked half a block away. Earlier, I had been annoyed at not finding a space closer to the club. Now I was grateful. I had a better chance of reaching it on foot and driving away unnoticed than of trying to start it up right there.

So I hustled off, teeth chattering, and remained well behind the crowd. My luck held. No one noticed and no one called out my name.

I paused at a pay phone and rang Sam Delaney, my editor. He answered on the first ring. I could imagine his face, his dark eyes, his strong hands, as he gripped the phone.

“Lanie? Where are you? I just heard over the police band. Are you all right?”

“I’m fine, Sam. Fine.” I told him the details and dictated the setup for the story.

“You coming in?” he asked.

“I’m on my way.”

I hung up, shivered and rubbed my upper arms, then hopped into my car. Sam would phone downstairs and tell the guys to hold the presses. Then he would start writing the story. By the time I got there, he would have all the basic stuff down.

I made myself focus on the story. Set all emotions aside. There was no time for them. No time to feel anything. That would came later, but right then and there, I didn’t want to feel anything, anyway. I wanted the comfort of detachment and reason.

Sam was the only one in the newsroom when I arrived. The place was as silent as a tomb. During the day, it was a human beehive. You heard typewriters clacking, phones jangling, and radios blaring. You heard the wire service printers thumping out endless reams of print and the whompof the pneumatic tubes shooting final edits down to the typesetters. In short, it was so loud the noise hit you like a wall when you walked in.

But in the evenings, the newsroom was deserted and the heavy silence had a tangibility of its own. Normally, you would’ve at least heard the rumble of the printers downstairs. But that night they were paused and waiting for the story of the Black Orchid kidnapping and the Cinnamon Club massacre.

Sam waved me into his office, the man-sized fish tank that sat at the far side of the newsroom. He was as handsome as always, and impeccably dressed. He wore a blue-gray shirt and a finely printed dark blue silk tie under a gray vest. He was at his typewriter, pounding the keys with a viciously accurate two-fingered hunt and peck. I tossed my purse into a chair and started reading over his shoulder.

I double-checked what he’d written, suggesting where to add color and detail. Then we switched seats and it was he who edited over my shoulder, smoothing phrases, rounding out sentences, making the copy strong, the telling swift and neat.

I couldn’t have worked this way with everyone. Sam was a wonderful editor, one of the best. He wasn’t just your advocate, but the advocate for your story. He helped untangle complicated ideas and pushed you to think of new angles. He saw potential, both in you and your piece. He was patient; he was funny. He was smart and he was kind. He was also the first man I’d dared to care about in the three years since my husband died.

Hamp had collapsed on a Seventh Avenue street corner, not ten blocks from our home. At thirty-seven years of age, he’d died of a heart attack. It came without warning, just one day out of the blue, like a hammer from the heavens, and he was gone.

Hamp’s passing had not only broken my heart, but left me terrified to love again. I hadn’t realized how much until Sam took over the newsroom. Now I was learning bit by precious bit to stop using grief as a wall against future pain and disappointment.

As Sam leaned over my shoulder, his clean male smell filling my nostrils, I felt a surge of joy, a terrified joy. I could’ve been one of the unlucky ones. It could’ve been me who caught a bullet and was on my way to the morgue. It could’ve been me who was stretched out with a tag on one toe. Instead, I was alive and here in my newsroom with Sam.

“He was jumpy,” I said of the killer. “Shot up the place for no reason.”

“Sounds like an amateur.”

His office phone rang and he snatched up the receiver. From his side of the conversation, I gathered that it was the typesetter wanting to know how much longer we’d be. I glanced at the wall clock. We had another five minutes, tops, to get the story done. The whole paper was on hold. An entire crew was waiting.

But that’s not what worried me.

Sam hung up. Over the next four minutes, we checked the copy once more, and I took comfort in his nearness as he read along with me.

“That last paragraph,” he said, “it—”

Outside Sam’s office, the main newsroom door banged open. I looked up and saw the source of my worry stride in. Detective John Blackie. I knew him from when I covered crime for the Harlem Age.Now I worked for the Chronicle, but our paths still crossed, because every now and then my writing about highbrow Harlem meant writing about highbrow crime.

“Sam, you might have to finish this without me.”

He didn’t answer.

Blackie rapped sharply on Sam’s office door, but didn’t wait for an invite. He stepped inside, saw what we were up to, and said, “I hope you’re done with that, Lanie, cause I’m gonna need you to come with me.”

“Give me just a minute.”

He shook his head. “Sorry, it can’t wait. I got a boatload of witnesses who say you were there tonight, at the Cinnamon Club. You saw the whole thing.”

“Sure I did, but what about the witnesses? They weren’t just looking at me.”

“None of them got as close to the shooter as you did.”

“What about the Ralston girl? She stood right next to him.”

“Are you kidding? The poor kid’s scared witless. She can barely remember her own name.”

There was no use in arguing. I glanced at Sam.

“It’s okay,” he said. “I’ll finish up here, then I’ll join you.”

“No need for that,” Blackie said. Then he saw the look in Sam’s eyes. “All right, but don’t expect me to wait till you get there.”

I picked up my purse and went to Blackie, my reluctance obvious.

“Where’s your coat?” Sam asked.

“You ran out and left it, didn’t you?” Blackie said.

Sam took his coat down from the rack and draped it around my shoulders. “Don’t worry, I’ll take care of your baby here.” He nodded at the typewritten pages. “Then I’ll come to the station, make sure everything’s going all right.”

Chapter 3

Blackie kept a firm grip on my upper arm. He pushed and shoved and barked orders, cutting his way through. “Move, people! Move!”

Those forced aside regarded me with interest, bewilderment, and envy. “Hey, why does she get to go in?” one reporter yelled out. I knew most of these fellows and was on good terms with many of them. But professional friendliness can evaporate in the heat of competition. Some of them looked about ready to throttle me.

Then I was through the crowd, up the steps, and into the clubhouse.

Inside was more nervous, agitated, fearful humanity. There were a number of people who’d been at the Cinnamon Club. Their faces were scraped, their clothes dusty and bloodied. They sat on benches, some in shock, some alone, some comforted by others who argued with officers about needing to get their loved ones home. And there were cops, cops everywhere. I’d never seen so many outside the St. Patrick’s Day parade.

Blackie guided me through it all. He took me down an ugly corridor to an even uglier back room. He left me there, “just for a minute,” and hustled off.

The closing of the door left a sudden quiet. It was a small room with three chairs and a desk. There were no windows, just walls, and they were bare and dirty. A bare bulb hung from the ceiling. The place was a closet, tight and claustrophobic. It made me feel like a crook, as though I’d done something wrong.

I took a deep shuddering breath. I wrung my hands, folded them over one another, and then wrung them again. I fumbled in my bag for a cigarette, but remembered that I hadn’t brought any. Sometimes I carried them for social events, when smoking was expected. It was one of those things that sophisticated people were supposed to do: smoke. But I’d never liked cigarettes, never enjoyed their bitter aftertaste, and they’d certainly never calmed me.

The “minute” passed and Blackie wasn’t back.

It was chilly inside the room. I was grateful for Sam’s coat and hoped he wouldn’t catch cold, running down to the station without it. Hugging myself and rubbing my upper arms, I paced back and forth. What a miserable night, and it was far from over.

The door opened and Blackie walked in, followed by a young woman. She was in her mid-twenties, had dark blond hair parted to one side, dark brown eyes, and wire-frame spectacles. She wore a dark blue shift and carried a thin pad and pencil. A stenographer.

Blackie introduced us, then we all sat down. When he offered me a cigarette, I shook my head and said, “Let’s get on with it.”

So began a grueling hour and a half. Under questioning, I gave a statement, repeated it, and repeated it again.

“A caper like this,” Blackie said, “it must’ve taken two people. One in the club, another with the getaway car. Did you see anybody else?”

I shook my head. “No.”

After Blackie was done, another detective came in—I didn’t catch his name—and he had questions too. Some Blackie had asked; others were brand new. Most I didn’t have answers to.

Eventually, I was taken to another room. There I sat with a police artist and tried my best to supply details I didn’t have but they desperately needed.

I saw Lucien Fawkes in the corridor. I’d forgotten about him—he must’ve been in his back office when it happened. Was he the one who’d called for help?

We gave each other a cursory nod, but didn’t speak. The bulls were keeping him busy. I could imagine the kinds of questions they were throwing at him, because they’d thrown them at me too.

How well do you know the Black Orchid? What kind of person is he? Did he ever give any sign of being in trouble? Did he worry that someone was after him?

I could honestly say that I’d only had that one real conversation with the man, and that much of what he’d told me was fluff. But Fawkes wouldn’t be able to get off so easily. He was Queenie’s boss, had worked with him for months. Surely he’d gotten to know his headliner in that time.

I would’ve given my eyeteeth to listen in. I doubted they were getting anything useful out of Fawkes, but I wished I could’ve been a fly on the wall just in case.

Chapter 4

“They got anything?” he asked.

“Don’t think so.”

“When we get you home, I’m going to run you a nice, hot bath and—”

“Sam.” I came to a stop, hesitated.

“Yes?”

“I think I’d rather be alone tonight.”

I could feel his surprise, then his frustration. His lips tightened. He took a moment and glanced away. When he spoke, his voice was calm and controlled.

“You’ve been through hell. I know that and I’m not the kind of man to take advantage of it. I thought you knew that—”

“I do.”

“Then why—”

“I just . . .” I sighed. “Need to be alone.”

“That’s exactly what you don’t need.”

I didn’t answer him.

He gripped me lightly on the shoulders. “All I want to do is hold you, make you feel safe. Please, let me do that for you.”

I closed my eyes. A part of me wanted to give in, but another part, a stronger part, refused. “I’m sorry. I can’t.” I pushed him away, gently but firmly. I wanted to say something to assuage the hurt in his eyes. How could I explain that this had nothing to do with him? I gestured back over my shoulder, toward the police precinct. “When I was in there . . .” I shuddered, unable to go on.

“That’s what I mean. Now’s not the time to crawl back into your widow’s shell. You shouldn’t be alone.”

I bit my lip, then slowly but deliberately shook my head. “You’re wrong.”

He took a deep breath, glanced upward, and slowly blew out his cheeks. For a moment he was silent, praying no doubt for patience. Then he summoned that slightly tense but loving smile he so often had to use with me. I reached up to kiss him. It wasn’t the kiss I wanted to give him; it certainly wasn’t the kiss he deserved. He turned his head at the last minute and I couldn’t be sure it wasn’t on purpose. So I ended up kissing his cheek. His skin was warm and he smelled good. For a split second, I regretted my stubbornness—but only a split second.

Once we reached the car, he walked around to the driver’s side and opened the door for me. I started to take off his coat to hand back to him, but he told me to keep it.

“It’s okay,” I said. “It’s warm in the car.”

“Not really.”

“I only have a short ride home.”

“You’ll need it tomorrow, until you can make it back to the club and get your coat.”

“What’ll you do?”

He shrugged. “I don’t need a coat, not when I have you.” He put a hand over his heart. “Thoughts of you keep me warm through and through.”

I had to smile. I climbed in, behind the wheel.

He shut the door and bent to speak through the window. “Get some rest.”

I felt guilty. “Sam, about coming home with me. I—”

He shook his head, a crooked smile lighting his face. “Naw, baby, you don’t have to apologize. You don’t ever have to apologize to me.”

He leaned into the window and gave me a light kiss, one that despite its brevity conveyed wistfulness and regret. Then he stepped back with a bow, making an obvious show of getting out of my way. I bit my lower lip, my heart heavy, my mind confused, and started to pull out. On impulse, I stuck my hand out the window to wave, but I was too late. He’d already turned away.

Chapter 5

Bad idea.

It all came back. Images of Charlie Spooner, his chest ripped open; of Queenie’s face and the fear in his eyes; I could smell the gun smoke, hear the screams, see the bullets tearing up the floor in front of my face. And always in the background, Queenie’s cries. I could see him being dragged through that back door. Hear him, once proud, now begging for someone, anyone, to save him; and I could see myself, hiding under a table, heart pounding.

I sighed, opened my eyes, and rubbed my forehead. I had done nothing to help Queenie; in retrospect, I wasn’t sure there was anything I could’ve done. But that didn’t stop me from feeling guilty. No, not just guilty, but dirty, used, and utterly spent.

I’d covered crime for years at the Harlem Age,so this wasn’t the first time I’d witnessed violent death. It wasn’t the first time I’d witnessed a shooting, either. But it was the first time I’d seen a friend, Spooner, shot before my eyes. It was the first time I’d been talking to one of the victims only minutes before the crime. And it was certainly the first time I’d been made an accomplice.

Or was it?

One day, when I was a child, maybe five or six, in Virginia and out with my mother, we were walking past a park. It was the middle of the afternoon. I don’t remember where we were going, but my mother was in a hurry to get there. I also remember looking up and seeing two men. They held a woman by the arms, and were dragging her toward the park. She was struggling, weeping, looking around for help. All I recall of her face is her fear. But I can still see her dark velveteen hat, her dark gray coat. She had a black leather purse with a silver handle slung over one arm. I can still hear her, so terrified she couldn’t scream. She was babbling, begging for help. She kicked and tried to dig her heels into the ground. But it didn’t matter—they were pulling her inexorably into the darkness.

People were walking past, stone-faced, my mother included. How could they? Couldn’t they see what was going on? Why weren’t they helping? I tugged at my mother’s sleeve and pointed. She hushed me. “It’s none of our business.” Look straight ahead, she told me, but I couldn’t. My eyes followed that woman into the bushes.

I never found out what happened to her, but I’ve always wondered. I’ve always been haunted by the thought that I could’ve done something. I’ve always felt puzzled and somehow dirtied by the fact that my mother refused to do anything.

I hadn’t thought of that woman in years, but I thought of her now. I thought of how we’d helped those men do whatever they did to her, simply by doing nothing.

Of course, I was a child back then. I couldn’t have done anything. But I wasn’t a child anymore. I had to take responsibility for my role in the crime that had just taken place.

I went over it again, but didn’t see what I could’ve done differently. And I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

My hands were ice cold and, despite Sam’s coat, I was shivering. I needed to get out of the car, go inside, get warm. But I couldn’t bring myself to move. Instead, I sat there, staring out the windshield, at the quiet, familiar street.

I lived in a small, highly insular part of Harlem dubbed “Strivers’ Row,” an appellation that began as a term of mockery but soon became a badge of pride. The enclave’s distinctive town houses were home to many of Harlem’s most renowned “strivers,” including entertainers, lawyers, doctors, and other professionals.

The mention of Strivers’ conjured up images of red Roman brick or Georgian yellow town houses. It meant private gateways and courtyards, quiet dignity and distinction, all designed by some of the best architects of the day, including Stanford White.

Strivers’ Row consisted of only two blocks—West 139th and West 138th Streets—and it ran only one block east and west, from Seventh to Lenox Avenues, but those two blocks contained some of the most elegant town houses in all of New York City.

Of course, I was partial.

I glanced over at my house, sitting there looking so pretty. Hamp and I had purchased it shortly before his death. Since then, the house had become a source of both pain and comfort. Everywhere I looked, I saw signs of Hamp. To live there meant living with a continual reminder of what I’d had and what I’d lost.

There was one part of the house where memories of him had been softened, if not fully overlaid, and that was the kitchen. Sam had labored long and dusty hours in there to build me a set of cabinets. He’d started over the Christmas holiday and worked on them every weekend, assembling them bit by bit, until they stood lined up against the walls like perfect soldiers. Like Sam, they were solid, dependable, and attractive.

I thought of those cabinets now. How I’d fought to keep Sam out of my heart, out of my home. Then, in December, after the terror of the Todd case, I turned to him. He was everything he appeared to be, and for a few weeks I’d known some semblance of peace.

But only a few weeks.

Soon, the fear, the reluctance to become involved again, resurfaced with a vengeance. I knew I could trust him. At least, I thought I could—there was so much about him I didn’t know. He was singularly silent about his past.

But that wasn’t it. Lack of knowledge about his past wasn’t the reason I’d pushed him away.

What then?

I didn’t know. Earlier in the evening, when I’d first gotten out of the club and arrived at the newsroom, I’d been so glad to find him there. There was no place on earth I would rather have been, and I was grateful, so very grateful, that I didn’t have to be there alone. Thoughts of him had sustained me even through those grueling police interviews.

When had my feelings begun to change? Had it been while I waited for the portrait artist?

Yes, perhaps then. I’d sat in the regular waiting room, fully exposed to the jostling misery of that frantic crowd. By the time I sat down with the artist, all I could think of was getting out of there, of going home and being alone.

Totally, restfully, blissfully alone.

Sam hadn’t understood that. I hadn’t understood it myself and couldn’t explain it to him.

I frowned.

Then again, maybe he hadunderstood. There were many times when he seemed to understand me better than I understood myself. Perhaps this was one of them. He’d understood me and known better. Perhaps he was right and I was wrong.

Exhausted, I again allowed my eyes to close for a second. Memories from the nightclub instantly flared up once more, images of the agony in Charlie’s face, the terror in the Ralston girl’s eyes, of the man and woman lying slumped in their seats, the acrid stench of gunpowder, of blood and fear. I opened my eyes, gasping and feeling sick.

My gaze traveled up the long empty street. Everyone else on this tranquil block was in bed. No. Lights did burn in one window: diagonally across the street, at the home of the Bernard family. Hmm. Was it the miseries of the evening keeping them up, as with me? I hoped not. I hoped that it was simply a good book.

For a moment, I had the wild wish to go over there, ring their bell, talk to them, enjoy their normalcy. But I couldn’t do that. It wasn’t just that it was late—well past two in the morning—it was also that, well, I’d been a poor neighbor to the Bernards. I’d known them through my husband, but I’d rarely seen or spoken to them since Hamp’s death. My fault, not theirs.

My gaze moved down the street. Other than the Bernards’ single light, all the windows along Strivers’ were dark. This was a street of couples and families. Behind most of those windows were husbands and wives, cozied up together, finding comfort and strength in each other’s company. I could’ve had that tonight, but would it have been real and lasting, or just something to get me through the loneliness of the night? Did it matter?

I drew a deep breath and let it out slowly.

Sometimes, I didn’t understand myself. I really didn’t.

With another deep sigh, I turned off the engine and stepped out of the car. I went up the stairs to my front door, unlocked it, and entered, but paused in the vestibule.

I peered at the gleaming stairway leading up to the second floor and beyond. I thought of all those beautiful but empty rooms, more than ten of them. For the first time in a long while, the house seemed achingly empty. I’m not superstitious, but in my heart of hearts, I’ve always believed that houses are alive, that perhaps they’re imprinted by the thoughts of their creator and the succeeding hopes and sorrows of their owners.

For a moment, I felt as though the house itself was speaking to me. I could sense its disappointment. I wasn’t the only one to have lost dreams; the house too felt a wrenching void. It was a big place, with generous spaces. It was meant to be filled with noisy, laughing children and grumpy but lovable relatives. Instead, it stood empty.

I knew I had to change, to do something, but how?

It was too much to think about just then.

The house was warm—I could feel the warmth on my skin, but it didn’t touch the chill inside me.

I hung up Sam’s coat, then went upstairs. I undressed, slipped into a lace cotton gown, and slid under the covers. I lay there shivering for a while, then got up and fetched more blankets. They didn’t help.

Fact was, I longed for a man’s arms to hold me. That night, especially, after what I’d gone through. Was I going to spend the rest of my life like this? I didn’t want to.

As it so often did, my gaze moved to Hamp’s photo on the night table. I couldn’t see the details of his image in the dark, just the outline of the silver frame glinting from a stray bit of moonlight. It looked cold.

Like the grave.

My beloved husband was in the grave. He was gone. Really, really gone.

I closed my eyes and the sobs erupted, harsh, hot tears. I was alive, yes, but I felt cold inside, as cold as the dead.

Copyright © 2011 Akashic Books

Persia Walker is the author of the 1920s Jazz Age novels Harlem Redux, which the Boston Globe called “a full, vibrant portrait of that storied era when Harlem's pulse was the rhythm of black America”; and Darkness and the Devil Behind Me. Her short story “Such A Lucky, Pretty Girl” appears in the anthology The Blue Religion. A native New Yorker fluent in German, she is a former news writer for the Associated Press.

Interesting how the story moves from fast action and colorful character to self-reflection. Harlem’s a real character here, as is the empty house itself. Nice.