or A Good Nemesis is Hard to Find

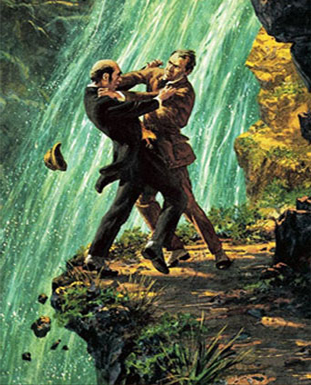

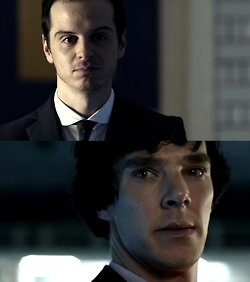

The Wikipedia entry for the word nemesis states, “‘Nemesis’ is now often used as a term to describe one’s worst enemy, normally someone or something that is the exact opposite of oneself but also somehow similar. For example, Professor Moriarty is frequently described as the nemesis of Sherlock Holmes.” True enough, but for no good reason whatsoever, so far as the canon is concerned. “The Final Problem” commences when Holmes shows up at Watson’s residence late one night, being suave and stoic about the eighty-six near-deaths he has suffered since afternoon tea. The culprit? Professor James Moriarty, the Napoleon of Crime, the archenemy of the private consulting detective. Watson’s response? Never heard of him. (Whether or not Doyle ever blushed at this literary misstep is doubtless lost to the mists of time.) The case continues, Holmes and Watson running for their lives, the Professor never once appearing in person excepting an incident when he is inside a train screaming past, and then soon enough—perhaps out of sheer narrative boredom—our hero graciously allows himself to “go gentle into that long goodnight,” Holmes and Moriarty having shared precisely zero minutes of active page time. For the master of the short story form, “The Final Problem” is a remarkably poor showing.

Here's a spoiler-free PBS Preview of “The Great Game.”

Apart from the very tense interludes involving the semtex-draped kidnapping victims, screenwriter Gatiss delivers still more plotsome intrigue by sending John (and later Sherlock) off to solve the case recorded by Doyle in “The Bruce-Partington Plans,” an adventure superior to “The Final Problem” in every conceivable way. Secret government missile plans have disappeared, and the corpse of the prime suspect is discovered on a train track, the body quite crushed; where, meanwhile, is the corresponding blood? Sherlock’s solution to this case is one of the most satisfyingly deft in the original stories, and Gatiss gives canon fangirls and boys a wonderfully obscure in-joke by naming the culprit after the villain in Doyle’s “The Naval Treaty,” another stolen-government-secrets adventure. These people, these people at the BBC: they know what they are talking about.

Of course, “The Great Game,” in the meanwhile, is not “The Final Problem,” because—despite a hair-raising cliffhanger—we already know from the writers that Sherlock does not meet his “Reichenbach” until the close of BBC's Sherlock season two, which begins filming in May of this year.

This gives the producers an opportunity to expand on the relationship between John and Sherlock, which is at once the heart and the backbone of the original material, and of which Gatiss recently said at the Kapow convention, “You can’t just go back to: ‘You have no emotions.’ ‘I don’t care.’” Steven Moffat, meanwhile, said of the Holmes-Moriarty rivalry on a BBC1 talk program, that “In a way Moriarty is the man who makes Sherlock a hero. . .he’s a rather amoral character Sherlock Holmes, so you want someone for him to respond to that turns him into the hero he’s sort of destined to be.” It’s admittedly a darker vision of Sherlock Holmes than the one written by Doyle, for the canonical Holmes’ honor-and-justice-meter is almost unfailingly sound save for one glaring incident *coughREICHENBACHcoughcough*. However, with three excellent episodes under their belts, each of which give Jim Moriarty’s character arc far greater play than the half-hearted sneeze Doyle afforded it, in my opinion they can consider their nemesis groundwork to be well and truly ahead of the game.

Lyndsay Faye, author of Dust and Shadow and The Gods of Gotham, coming Winter 2012 from Amy Einhorn Books/Putnam. She tweets @LyndsayFaye.

A well thought out analysis of “The Final Problem.” I’ve always loved this story and never looked at the story’s shortcomings. I’m looking forward to the latest filmed version.