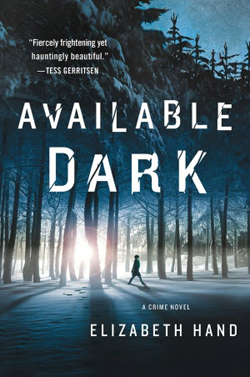

Photographer Cass Neary is already wanted by the police for questioning when she receives a mysterious job offer that sends her to Helsinki, where an iconic fashion photographer shows her a trove of gorgeous photos depicting ritual killings. After narrowly escaping death herself, Cass flees to Iceland, where she finds a former lover and a legendary, exiled musician. Soon, unsolved murders are multiplying faster than Cass can run.

Photographer Cass Neary is already wanted by the police for questioning when she receives a mysterious job offer that sends her to Helsinki, where an iconic fashion photographer shows her a trove of gorgeous photos depicting ritual killings. After narrowly escaping death herself, Cass flees to Iceland, where she finds a former lover and a legendary, exiled musician. Soon, unsolved murders are multiplying faster than Cass can run.

Chapter 1

There had been more trouble, as usual. In November I’d headed north to an island off the coast of Maine, hoping to score an interview that might jump-start the cold wreckage of my career as a photographer, dead for more than thirty years. Instead, I got sucked into some seriously bad shit. The upshot was that I was now back in the city, almost dead broke, with winter coming down and even fewer prospects than when I’d left weeks earlier. I dealt with this the way I usually did: I bought a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, cranked my stereo, and got hammered.

When I finally came to, it was dark. Sleet rattled against a greasy window. In a corner of the apartment, a red light flashed beside a stack of old LPs: I’d turned off my phone but forgotten the answering machine. I lurched toward the blinking light, unsure if it was early morning or night, yesterday or tomorrow.

“Cass. What the hell did you do?”

I rubbed my eyes, head throbbing.

“. . . don’t know how you got that photo of my mother, but you better call me fast. Sheriff Stone wants to talk to you, also that guy Wheedler from—”

I hit erase and skipped to the next caller.

“This is a message for Cassandra Neary from Investigator Jonathan Wheedler of the Maine State—”

I erased that one, too, and all the rest without listening to them, just for good measure. Then I took a shower, waiting for ten minutes before the water pressure amped up to a scalding trickle. That’s what thirty-odd years in a rent-stabilized apartment on the Lower East Side will buy you. I dressed— moth-eaten black sweater, ancient black jeans, steel-toed Tony Lamas, the battered leather jacket I’d bought at Goodwill decades ago—and went outside to forage for coffee.

It was night. Streetlamps gave off a smeared yellow glow. The financial meltdown hit my neighborhood hard—not that I had any sympathy for the unemployed hedge-fund assholes and fashion models who spent their afternoons whining into their iPhones in front of the Dries Van Noten store. Before the crash, this part of the city looked like a cross between a Downtown USA soundstage and the Short Hills Mall; instead of stepping over junkies, I maneuvered around rat-size dogs in Juicy Couture sweaters and designer diapers. Now I wondered how bad things would have to get before Jack Russell terriers showed up on the menu at Terrine.

But I couldn’t afford to move. I’d been in the same place since the 1970s. The landlord had been trying to get rid of me for years; eviction notices had piled up in the weeks since I’d been gone, so I made a quick phone call to my father up in Kamensic Village.

“Talk to Ken Wilburn,” he said. “He’ll take care of it for you. Are you back from Maine, Cass? Any more trouble with that? Come home, and let’s have dinner one night.”

I said I’d think about it and hung up.

Tonight I kept my head down against the sleet and wished I owned a warmer coat. I passed a line of anorexics waiting to get into a restaurant specializing in downtown comfort food: mashed heirloom potatoes, truffle macaroni and artisanal cheese. As I walked by, one of the skinny girls laughed. I stopped, pivoting so that my boot’s steel tip grazed her Bally Renovas.

“Did you say something?” Skeletor met my eyes and blanched. “Didn’t think so,” I said, and kept going.

Back in the day, my nickname had been Scary Neary. Most of the people who called me that are dead now. No direct causal relationship, just bad drugs and worse luck. I’m nearly six feet tall, all speed-fused nerves and ragged dirty-blond hair, with a fresh scar beside my right eye, souvenir of my trip to Vacationland: a walking ad for Just Say No.

I skipped Starbucks in favor of the all-night Greek diner around the corner, found a booth in the back, ordered black coffee and a rib eye, rare. I was well into my steak when someone slid into the seat across from me.

“Hey, hey, hey. Cassandra Android.”

I winced. Phil Cohen, onetime rock journalist manqué, now the mastermind behind a celebrity blog called Early Death. Phil was a local bottom-feeder, one or two steps above or below me on the social ladder, not that anyone was counting. He was also my most reliable source for speed.

I hadn’t seen him since I’d been back. From the way he looked, alarmingly bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, the downturn in the economy hadn’t hit his corner of Hoboken. Phil wasn’t a bridge-and-tunnel guy; more just a tunnel guy, especially when you factored in his ratlike ability to scrounge a living in the dark.

“Phil. How’s it hanging?”

“Not bad, not bad. Hey, I saw your photo got picked up by The Smoking Gun. Nice work. How the hell’d you do that?”

I pushed away my plate. “Fuck off , Phil.”

Phil looked wounded. “I told that German editor to get in touch with you—the lady from Stern? They pay good money; I figured you could use a taste.”

“You put her in touch with me?”

Phil nodded. He was fidgeting so much he looked like a life-size bobblehead. “Yeah, sure, how’d you think? Good thing your old man’s a lawyer.”

I glared at him and finished my coffee. Phil was the one who’d sent me to Maine; he’d lied about the interview he’d supposedly lined up, and lied about just about everything else, too. His connection turned out to be a photographer named Denny Ahearn, whose favorite subjects were decomposing bodies in trees. Long story short: Denny went overboard off the Maine coast and was now presumed dead. The story got some press but quickly ran out of steam since the killer was gone and the remains of only two victims had been recovered.

My own involvement in everything was a little shaky. I kept a low profile until I was safely back in New York, where an editor from the German tabloid weekly Stern had rung me a few days after my return.

“I so admire your work, Cassandra.” Her voice had risen slightly. “Your photo book Dead Girls—that was brilliant. I was a big Bowie fan then, you know? We’d give you an exclusive. . . .”

She had been disappointed when I told her I didn’t have any photos of the serial killer or his victims. I’d been disappointed, too, when she named the figure they’d pay. Then I remembered the roll of film I’d shot on the island but hadn’t yet developed.

It had been a weak moment for me. Most of my moments are like that. Finally I said, “You familiar with a photographer named Aphrodite Kamestos?”

“Aphrodite Kamestos? Of course. She’s very well known here. Helmut Newton admired her work.” The editor hesitated. “She just died, too, didn’t she?”

I hadn’t told her I’d watched Aphrodite die, or that I’d lied to the cops about it so I could avoid a conviction for voluntary manslaughter. I did a quick mental rundown of where I could cadge a few hours in a borrowed darkroom so I could process the film without anyone else seeing the images. “Yeah. I might have an image of her, kind of a memento mori. Like a death mask.”

“A death mask?”

“Sure, you know. Something taken right after she died.”

The editor had moaned. “Oh, that would be so great.”

Now I stared across the table at Phil. “Yeah, good thing my old man’s a lawyer. So, you got anything in that little black bag for me?”

Phil’s eyes rolled back in his head like he was communing with the spirit world. “Focalin.”

I stuck my hand under the table so he could drop a Baggie into it.

“You’ll like this, Cass. Nice and easy, timed-release, no edge. And probably I shouldn’t say this, ’cause I’d hate to lose your business, but you could see your doctor, he’d give you a scrip. Then you could get your health insurance to pay for it. Some Zoloft wouldn’t kill you, either.”

“Phil. Do I look like I have fucking health insurance?”

“Good point. Here, you want this?” He set a tiny glassine envelope on the table, then flicked it at me. It landed on my lap. “Touchdown.”

“What is it?”

“Crystal meth. Very pure, Cass; we’re talking Pellegrino, Fiuggi, all that shit. No one else wants it these days, but this is the stuff. Guy who used to be in the refrigerant industry, he still cooks with Freon. He’s got a nice little stash of CHCs, but there ain’t no more where this came from. I’ll give you a deal on it, Cassie. As a Christmas present.”

“Christmas is over, Phil. But yeah, I’ll take it.” I peeled off a few bills to cover my meal, handed him a couple more, then stood. “Later.”

He pulled my plate over and began to eat the rest of my steak. “Yeah. Write if you get work.”

I walked back to my apartment, taking care that my cowboy boots didn’t send me flying as I navigated the slush-choked sidewalk. I’d taken the Stern payment and had the boots resoled, but they still weren’t shit in bad weather. The rest of the money had gone to cover unpaid bills, plus a small retainer set aside for Ken Wilburn so I could hang on to my place for another year or two.

And that was it. I’d already gotten fired from my longtime job at the Strand Bookstore, no great loss save for the five-finger discount I’d exercised over the years, building up a small library of expensive photography books. Even that was a victim to changing times, as store security had amped up to TSA levels, with metal detectors and bag checks before you set a foot on the floor.

But being broke wasn’t really the worst thing. I’d spent most of my adult life as a burned-out underachiever, working in the Strand’s stockroom, drifting from one bed to another. For a few years in my twenties I’d been able to trade on the flash success I’d had with Dead Girls, my first and only book of photographs. Everything since then had pretty much been aftermath.

Still, through it all I’d always had the Lower East Side and the shadowy image behind my retinas of what it had once been: that 3:00 a.m. wasteland I’d fallen in love with when I was eighteen, shattered syringes and blood on the lip of a broken bottle, guitars and drunken laughter echoing through an alley where kids nodded out while I shot their pictures. The way something was always moving at the corner of my eye; the way the city was always moving, morphing into something new and terrible and beautiful.

The terror I knew on a first-name basis. On my twenty- third birthday I was raped outside CBGB. The scars are so old, as the song goes, now part of a faded tattoo I got on my lower abdomen to hide the bloody scrawl left by a zip knife. But even so, I could still sometimes find the silver- nitrate city inside the real one, if the light was right and I’d had enough to drink, scored enough amphetamine to make my heart keep pace with the strobe of my camera’s flash.

Now all that beauty was gone. I was too old and too broke to go looking for it elsewhere. I’d spent too much time alone, skating on alcohol and speed, not noticing the ice beneath me was rotten and the water killing cold.

The last person who said she loved me died on 9/11. I’d forgotten what she looked like. I was a burned-out, aging punk with a dead gaze, a faded tattoo, and a raw red scar beside one eye. In Maine I’d spent more time with other people than I had in years, maybe decades. There’d been a few moments when I’d held my battered camera and felt the way I did long ago, when I first stood in a darkroom and watched another world bloom on the emulsion paper in my hands.

But that feeling was gone; that world. Since my return to New York, I’d begun to have night terrors, paroxysms of pure horror, where I would see a black figure above my bed, smiling as he reached for my throat, and woke to my own muffled screams, heart pounding like a fist inside my chest. I felt strung out, wasted in every sense of the word, terrified of sleep and almost as afraid to leave my squalid apartment. The edge where I’d lived for all these years was starting to look like a precipice. I figured it was a good time for a short visit with my father. I crashed for a few hours back in my apartment, woke, and swallowed a couple of Phil’s white tablets; then headed to Grand Central to catch the first train to Kamensic.

Chapter 2

The sleet that had made the city a skating rink turned to heavy snow when the train left Valhalla. By the time we pulled into Kamensic, I could see cars sliding across the southbound lane of the Saw Mill, and the beacons of emergency vehicles flashing like Christmas lights in the distance.

My father was waiting for me at the station. I’d called him before I left the city; he’s an early riser, up before dawn even at the darkest time of year.

“Hello, Cass.” He dipped his head to graze my cheek in a kiss, zipped his old L.L.Bean parka, then headed toward the parking lot.

“You didn’t have to pick me up. I told you I could walk.”

“Did you see it’s snowing?” he asked, and we drove home.

Since the late 1960s my father has been the Kamensic Village magistrate, holding court on alternate Tuesdays and otherwise tending to a few old legal clients from his basement office in the house where I grew up.

The town had turned into a junk-bond trader’s Disneyland since then. Most of the old colonial houses were now trophy second homes, or teardowns turned McMansions, empty save for the shriek of alarm systems set off by barking dogs, and a seasonal army of workers bused in from Stamford, wiry Latino men wielding lawn mowers, leaf blowers, and, this morning, snowblowers. Martha Stewart owned a $20-million cottage outside town, where she’d spent the last few years trademarking the name Kamensic for a line of outdoor furniture that cost as much as a semester at a Baby Ivy.

I hated going back, though I was cheered to see the storm had knocked a giant oak onto the most recent addition to a neighbor’s house.

“Their alarm was going all night,” my father said as we pulled into the drive. “I tried calling the owners in the city, but they won’t pick up their phone.”

“They’re getting a lot of snow inside their new addition.”

My father smiled. He’s the only person in Kamensic who still mows his own lawn.

We ate breakfast, then read The New York Times. We didn’t talk all that much, but I was used to that. My mother died in a car crash when I was four, an accident that left her impaled on the steering wheel and me rigid and staring, wide-eyed, when the police found the wreckage. Since then, my father’s basic rule of thumb has always been that as long as I didn’t get hauled in front of his court, he wouldn’t ask too many questions.

“How was Maine?” he asked.

“Cold.”

“Did you stop in Freeport?”

“No.”

He stood and gathered a pile of papers from the sideboard. “I have a few things to take care of downstairs.”

He started for the door to the basement, stopped, and turned. “Oh, Cass—this came for you.” He pulled an envelope from the sheaf of papers and handed it to me. “You’re not in default on your student loan, are you?”

This was a joke. I’d dropped out of NYU in my freshman year, which was about the last time I’d received any mail at this address. I looked at the envelope, puzzled. “When did it come?”

“Last week.”

He went downstairs. I walked into the living room, eerily blue-lit from the snow whirling outside, sat, and stared at the envelope. Thin, airmail-weight paper, with my name and address written in black cursive ballpoint ink. Painstaking, almost childish handwriting, like someone trying to make a good impression. I felt the tiniest frisson, somewhere between dread and exultation.

I knew that writing—or had known it, once.

But the memory was gone now. The oversize stamp showed a snow-covered expanse with bands of green and violet rippling above it.

Island 120.

No return address. Who the hell did I know in Iceland? I squinted, trying to read the postmark.

Reykjavík.

The fragile paper tore when I opened it. Inside was a newspaper clipping in Icelandic. It featured a grainy black-and-white image of a fir-tipped islet with a caption beneath: Paswegas, Maine, USA. I scanned the column until I recognized my name—Cassandra Neary.

So I had a fan in Iceland; someone who read Stern, maybe. I frowned and examined the envelope again.

There was something else inside. I removed it carefully.

It was a photo of a naked teenage boy, sprawled on an unmade bed. Grainy black and white, 4×6, the edges curled and faintly browned with age. He was wiry, his chest nearly hairless, half-erect cock shadowed in his crotch. His hair fell to his shoulders and framed an androgynous face: white skin, curved ridge of cheekbone, small chin, full lips, and slightly prominent teeth.

But it was those bruised eyes that killed me, eyes so deep set they seemed lined with kohl. He had his hands locked behind his head and gazed at the viewfinder dead-on. Not a come-hither stare but a wary, challenging look, as though he were debating whether to lunge across the bed and smash the camera or pull the photographer down beside him on the gray sheets.

I knew how that particular argument ended. I knew how they all ended, because I’d been the one behind the camera.

“Fucking hell,” I whispered. “Quinn.”

Thirty years ago I’d stood beside that bed, in a room less than a mile from where I sat now. I’d shot roll after roll of Tri-X film, always pictures of Quinn O’Boyle, sometimes clothed but mostly naked; before we fucked, afterward, during. Quinn hunched over his old Royal upright typewriter, or nodding out, or poring over his dog-eared paperback of The Return of the King. Walking toward the Kamensic train station, slumped in a booth at the Parkway Diner. Quinn and me standing side by side, a flare where my camera’s flash ignited the mirror that held our reflection. I’d ridden my bike to Mount Kisco to have the film processed at a grimy store whose proprietor specialized in “art photos,” an old man who chain-smoked Larks and smelled like Sen-Sen. He only raised an eyebrow once, when he handed me back my contact sheets and said, “Aren’t you kinda young for this?”

I turned the picture again and stared at the boy on the bed. I’d shot scores of photos. Hundreds, maybe. I’d stashed them in a wooden Chivas Regal box, but I hadn’t seen it, or any of the photos, in almost three decades. I’d ransacked my room, the house, the basement. I never found them.

And Quinn—he’d also disappeared. The two of us had broken into a local drugstore one night when we were eighteen. We weren’t caught. My little stash of Quaaludes saw me through my first year in the city, but by then Quinn had taken off upstate with a woman he met in Harlem one night. I was sick with desire for him, sick with rage, and terrified that I’d never shoot another photo worth looking at. I channeled it all into speed and the photos that eventually became Dead Girls. Around the time the book came out, I heard that Quinn had gotten popped for breaking into another drugstore up in Putnam County. He wrote to me from his parents’ house, where he awaited sentencing, desperate pleading letters, handwritten or typed on lined paper torn from a composition book. Sometimes he sent fragments of a story he was working on. Once he sent a Quaalude, crushed in transit to a smear of pink powder.

I never wrote back. When he left me, I felt as though someone had jabbed my eyes with a needle. Nothing looked the same after that. I’d honed my sense of damage on him, the bitter pheromone I’d inhale as I watched him hold a spoonful of brown powder over a gas flame till it melted into the chamber of a syringe. For years after he was gone, I still carried that acrid taste in my mouth and the afterimage of his eyes, the pupils swallowed by junk.

I had assumed he was dead. His family had moved to the Midwest. I never tried to track him down.

What the hell was he doing in Iceland?

“Who’s your letter from?”

I started as my father came into the room behind me. “No one. Just a newspaper article.” I slipped the photo back into the envelope and pocketed it, tossed the news clipping into the wastebasket. “Has anything else come here for me?”

“Not a thing. I need to head over to the town office for a few hours. Are you staying for dinner?”

I stared out to where trees and stone walls dissolved into a formless blur. “No. I have to get back. Can I catch a ride with you to the station?”

While he got ready I went upstairs to my old room. Nothing there remained of me, no posters or books, no clothing or record albums; just my old bed, now sanitized with a white chenille spread and white pillows. I took out Quinn’s photo, stood by the window, and stared at it. I felt a shiver of apprehension, a dark flash at the corner of my eyes, the lingering odor of scorched metal and blood.

Chapter 3

The train was delayed because of snow. By the time I finally slogged back to my apartment, it was dark. I ate some tuna fish out of the can, then settled at my ancient computer to Google Quinn O’Boyle.

I came up with nothing. No one in Iceland, no one who looked or sounded like the man he might have become, the kind of guy who’d send a nude photo of himself to the teenage lover he hadn’t seen in thirty years.

After a few minutes I gave up and scanned my e-mail. Nothing but spam.

Or almost nothing.

From:derrabe@norwaymi-dot-com Subject: Photo Op

Dear Cassandra Neary,

I am a longtime admirer of your masterpiece Dead Girls and saw your photograph of the late Aphrodite Kamestos in Stern. I am wondering if you would have interest in a brief professional consultation of some photos I am considering as an acquisition. . . .

Another weirdo. I started to delete it but stopped when I scanned the end of the message.

I would of course not expect you to perform this service gratis and would be happy to discuss it with you as regards generous remuneration for your time.

With respectful regards,

Anton Bredahl

I had better luck Googling this guy. He was the owner of an Oslo club called Forsvar, a former air-raid shelter that specialized in industrial music, death metal—stuff like that. From its Web site, it seemed like a lot of his customers hadn’t gotten over the bad news about Ian Curtis. The rest looked like they’d just come from Anvil’s anniversary tour. There were a few underlit photos of the club’s interior but none of its owner.

I sat for a minute and wrote my response.

Anton,

Sure, let’s discuss.

CN

I hit reply and went to pour myself a drink. When I returned, another message had already popped onto the screen.

Can you talk now? What is your phone #?

I stared out a gray window glazed with sleet. I finished my Jack Daniel’s, thought What the hell, and typed in my number. A minute later the phone rang.

“This is Anton Bredahl.”

“You’re quick.”

“I am more comfortable in conversation. First let me say I know your work—I have a copy of Dead Girls.”

“You and twenty-five other people.”

He laughed. The connection wasn’t great, a cell phone or Skype. He sounded younger than me—late thirties, maybe. Not much of an accent.

“Yes, it was hard to find,” he went on. “An American friend told me about it. I bought it from a dealer a few years ago, someone in Oslo here who specializes in photography. It is a valuable book now, did you know that?”

“So I’ve heard.”

“I paid one hundred and forty euros. The exchange rate was not so good, so—it was expensive. I should have waited until now, right?” He laughed again. “Someone should bring it back into print. It’s a good book. That is how I recognized the photo in Stern. The same eye, I thought. It’s good you’re taking photos again.”

“It’d be better if I was getting paid for it.”

This time he didn’t laugh. I finished my drink, wondering if I’d pissed him off .

“Yes, that is why I wanted to talk to you. I collect photographs.”

“The Stern photo isn’t for sale.” I’d already stuck the negs in various books around the apartment, a half- assed attempt at hiding them. “None of my stuff is for sale, sorry.”

“Oh, no.” He sounded slightly embarrassed—for me, I realized as he continued. “Actually, I was wondering if you would be interested in looking at some photos and perhaps assessing them. Not my own photos—I’m not a photographer. Photos I am thinking of acquiring for my collection. I think there is some overlap in our taste.”

“I kinda doubt that.” I paced to the kitchen and poured another drink. “I haven’t done anything since Dead Girls; you know that, right?”

“You did the Stern photo.”

I had a spike of paranoia—he was a cop, the whole Stern thing had been a setup to implicate me in Aphrodite’s death— but before I could hang up, he added, “Joel-Peter Witkin—I bought his work very early on. But it is his later photos that I find most beautiful—the ones of the cadavers, before they became too camp. I have a number of other photographs as well. Weegee, but also—well, my taste is fairly . . . esoteric. You understand?”

“Right.” I relaxed and knocked back the whiskey. “Yeah, I sure do.”

“Esoteric” has roughly the same relation to my camera work as “erotica” has to porn. This guy liked the photographic equivalent of rough trade—very rough trade, as in dead people. Witkin’s most notorious pictures center around cadavers and various body parts gleaned from morgues and hospital freezers, rearranged and posed to evoke images like the martyred St. Sebastian, or surrealist tableaux that would give Buñuel the creeps.

Bredahl said, “You like Witkin’s work?”

“Yeah. Some. The stuff that isn’t trying too hard. It’s beautiful.”

“Isn’t it?” His voice lifted. “So many people don’t perceive how beautiful it is, the way he sees the world. That image of the severed heads kissing is sublime.”

“I wouldn’t hang it in my kitchen. But yeah, it’s an amazing photo.”

Joel-Peter Witkin was definitely a somewhat esoteric taste. Also an expensive one: After Jesse Helms denounced his work as degenerate, prices went through the roof.

All this made me wonder why Bredahl needed me to take a look at his photos. Witkin was way out of my league. If I hadn’t flamed out in the 1970s, you might have found my name alongside his in the Wikipedia entry for transgressive art. As it was, I was barely a footnote. Still, I needed to eat. Or drink, anyway.

“So you want me to authenticate some stolen Witkin photos? I’m not a curator; I couldn’t give you an estimate of how much they’re worth or anything like that. But I could take a look at them.”

“No.” Bredahl paused for such a long time I thought the line had gone dead. “I don’t want you to make an assessment of their value. I would like your opinion. I would like the use of your eyes, as a consultant, someone who will tell me whether these pictures are authentic or not. The particular sequence I would like you to review is not by Witkin. These are a slightly different kind of photo. As I said, very specialized, very—”

“Esoteric?”

“Yes. Some people might find them quite off ensive.”

“Listen, if this is some kind of kiddie porn—”

“No, of course not. But I must be—how do I explain? Circumspect. More than anything, I need to know if these photos are . . . authentic. You understand?”

“No.” I swallowed the rest of my Jack Daniel’s. “Look, I don’t think this is going to work, okay? I have to—”

“I will cover all your expenses. Not in Oslo—Helsinki. And I will pay you six thousand euros.”

I did the math in my head.

“Yeah, well, okay,” I said.

“I’ll arrange your flights. Is Thursday too soon?”

This was Wednesday. “Thursday?” I’d only been out of the country once, on an ill-fated trip to Belize. I frantically rifled my desk until I found my passport under a stack of ancient contact sheets. It was valid for another year. “Yeah, Thursday’s great.”

“Excellent. Now . . .”

I gave him the info he needed to arrange the flight.

“I’ll e-mail you a link so you can look at a few things in my archive.” I heard him light a cigarette, then inhale. “What I’ve put online, anyway. Probably it would be good not to share this with your friends.”

I promised not to share it with my friends. Not that I have any. I had a sudden bad thought.

“Hey—you know a guy named Phil Cohen?”

“Phil Cohen? No.” “You’re sure?”

“I think so. Is that a problem?”

“No. That’s good. I’ll wait for your e-mail,” I said, and hung up.

Copyright ©2012 Elizabeth Hand

Elizabeth Hand is best known for her science fiction and fantasy work, which has earned her multiple awards, but her latest work is firmly in the thriller genre.

We offer cosmetics, skin care, hair care & fragrances with free delivery. Buy Makeup online from a wide variety of 100% original makeup in Pakistan!

Reward yourself with our appealing Bath towel Sets in Pakistan. Our Hand Towel in Pakistan are manufactured to the highest standard from start to finish. Shop Online!

We are the Best Family Lawyer in Karachi. Contact us Today for all your Child Custody, Adoption & Divorce related matters in Pakistan