Fans of Sherlock Holmes may be intrigued to know that the first known female sleuth in England was Anne Kidderminster (nee Holmes), a seventeenth-century widow who tracked down and brought her husband’s murderer to justice thirteen years after the crime.

Thomas Kidderminster was a gentleman’s son who’d been swindled out of his Hereford estate by his stepmother. Forging his way in the world, he became a steward to the Bishop of Ely, a profitable occupation that allowed him to later lease land from Sir Miles Sandys, a nearly impoverished noble.

Shortly after, in 1653, Thomas met Anne Holmes, a lady’s maid serving at an estate about six miles away. They married in September that same year.

During this time, Sandys began to run into serious debt, borrowing extensively from Thomas and many others in the community. Sandys’s debts continued to accrue, until he was finally thrown in Fleet prison, where he died. Unfortunately for Thomas, Sandys’s debtors began to come after him as well, claiming his profits from the land belonged to them.

In April 1654, Thomas asked Anne, now pregnant, to leave Ely and stay with friends in London, with the intention that he would join her after he extracted himself from Sandys.

For several weeks, Anne waited in London, but Thomas did not appear. Finally, the pastor who had married them stopped by while in London on business. When she inquired after the health of her husband, he informed her that her husband had set out for London nearly a month before.

Panicked, Anne contacted all Thomas’s business acquaintances and friends. Over the next few months, there were many false leads. “He’s travelled to Amsterdam,” one said. “He went to County Cork in Ireland,” another assured her. They even heard that he had fled to Barbados or Jamaica because of some vague fears of Cromwell. Each time, there followed frantic exchanges of letters to no avail.

In August 1654, after giving birth to their daughter, Anne received news that her husband had drowned during a voyage from Jamaica to Dunkirk. This time, she went to the shipping office and personally looked at the ship manifests. His name could not be found.

Over the next few years, Anne continued to make inquiries, living now with her sister in London. Finally, in 1663 there was a break in the case.

She had come across a True Account that described how bones had been discovered outside the White Horse Inn in Chelmsford (Essex). Comparing the dates, she realized that the corpse had been concealed at about the same time her husband had gone missing.

Even though her husband’s ghost did confirm the bones as his own (!), Anne did not rely on this specter as absolute evidence. She set out for Chelmsford the next day. Carrying her infant daughter in her arms, she walked thirty-eight miles to speak to the coroner and Justice of the Peace. From them she learned that the victim’s skull had been crushed from a blow to the back of the head.

Since she couldn’t prove the bones belonged to her husband, Anne did the next best thing: She began to make inquiries, looking for any witnesses who could testify Thomas had been at the inn ten years before.

With the help of the local coroner, Anne tracked down several servants who had worked at the Inn under the Sewells, the original owners.

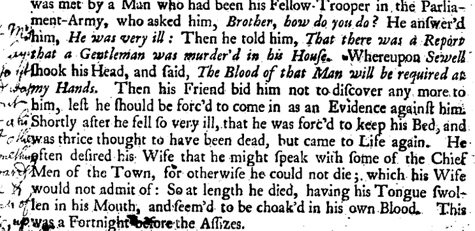

When she spoke to Moses Drayne, the Inn’s ostler, she began to suspect his involvement, especially when she noticed what looked like Thomas’s old clothes and even his horse (both confirmed later by Thomas’s former manservant). When Drayne was arrested, he accused the Sewells of the murder and they were questioned again.

While the Sewells denied any knowledge of the murder, the former maidservant, Mary, finally spoke out after nearly a decade of silence. When pressed by Anne, she admitted that Thomas—drunk—had let slip he was carrying a huge sum of money, information which she unfortunately passed on to the Sewells.

Later that night, as Mary testified, she heard raised voices in Thomas’s bedchamber and a violent thump. The next day, the Sewells told her that Thomas had left, but she was not allowed to clean his room, which was mysteriously kept locked. Moreover, she noticed his horse was still stabled and his shoes were still waiting to be blacked. Anther young servant—later shipped off to Barbados—told her that he’d seen the Sewells and their daughter burying the body.

After one too many questions, the Sewells let on that they had murdered Thomas, and that they would kill Mary too if she talked, or worse, blame the murder on her.

Lest anyone feel too sorry for Mary, the Sewells did pay her off with twenty pounds, which sealed her fate too. Like Moses Drayne, Mary was also sent to prison as an accomplice after the fact. Of the Sewells: Mrs. Sewell died during the plague, Mr. Sewell died during the trial, and their daughters were charged but not convicted for lack of evidence. So justice of sorts was enacted.

As the author of the pamphlet describing the efforts of this unusual sleuth concludes: “You see what pains, troubles, and expense she underwent in enquiry after her husband, in tracing out the murderers, and in the prosecution of them, having little or no assistance or advice but the divine providence, which assisted and directed her in the whole series of this affair.”

Certainly, in a time when there was no established police force, no modern forensics, and very dim attitudes towards women who asked too many questions, Anne Kidderminster demonstrates how an ordinary woman could go to extraordinary lengths in her relentless quest for justice.

Source: Anonymous (1688). A true relation of a horrid murder committed upon the person of Thomas Kidderminster, of Tupsley in the county of Hereford, Gent., at the White-Horse Inn in Chemlsford, in the county of Essex, in the month of April, 1654. Wing/ 853:61.

Susanna Calkins, the author of A Murder at Rosamund’s Gate, became fascinated with seventeenth century England while pursuing her doctorate in British history and uses her fiction to explore this chaotic period. Originally from Philadelphia, Calkins now lives outside of Chicago with her husband and two sons.

Great article! Just shared it @ [url=https://www.facebook.com/TheBletchleyCircleWatchers/posts/315318251945234]https://www.facebook.com/TheBletchleyCircleWatchers/posts/315318251945234[/url][url=https://www.facebook.com/TheBletchleyCircleWatchers/posts/315318251945234]https://www.facebook.com/TheBletchleyCircleWatchers/posts/315318251945234[/url]

Thinking about Anne Holmes as forerunner of Marples, The Bletchley Circle etc. Except she wasn’t fictional.