A few weeks ago, I did a book reading at Mt Waverley in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne. About twenty-five people came out—which was a reasonable number for me—and, as is usual with these events (or for anybody not named Rowling), the crowd skewed to an older demographic. I talked about my latest mystery novel and the Sean Duffy series itself, which takes place in Belfast in the 1980s. After the talk came the Q&A portion, and, as is also pretty usual for me, about a third of the audience was made up of Irish diaspora.

When the event was over, I signed a few books for people and had a chat with anyone who wanted to talk. An older lady who sounded like she had just stepped off the boat told me she had emigrated to Melbourne from West Belfast in the 1950s. She said that she loved my Sean Duffy novels, and, as a wee thank you, she had baked me a batch of potato bread. She explained that I was always talking in my books and on my blog about how impossible it was to get a decent breakfast outside of Ulster because nobody knew how to make Irish potato farls, the key ingredient to an Ulster fry. I thanked her profusely and said it was really too kind. When the event was over, I took the bus back to St Kilda. I put the potato bread in the fridge and went to bed.

Next morning, I got up early and demanded of my clan: “So who wants a real breakfast, today?”

Three skeptical pairs of eyes looked up from their electronic devices.

“What do you mean a real breakfast?” my eldest daughter asked.

“An Ulster fry.”

“What’s an Ulster fry?”

“Fried potato bread, soda bread, sausage, bacon, egg, and black pudding. We don’t have the soda bread, but a nice lady at my book event last night baked me some potato bread, and we’ve got everything else, so we can have a real Ulster fry!” I announced with enthusiasm.

“Sounds a bit much for breakfast,” my wife said.

“I’ll pass,” my eldest daughter said.

“No thank you, daddy,” my youngest daughter said.

“Don’t worry, I won’t fry it in lard. I’ll use butter, maybe a little olive oil,” I said, but I could see I wasn’t going to convince them with this healthy options spiel.

I sat down, grumbling. “All right, fine, I’ll wait until you lot have gone, and I’ll make it just for me.”

Half an hour later, I had the house to myself. And, yes, I know it's not heart-healthy food. I, myself, wrote the joke about Belfast in the ‘70s looking like Logan's Run because all men over the age of 30 had had an Ulster fry-induced heart attack. But it’s delicious, and as a once in a while treat its fine. So, I melted a little butter and olive oil in a pan and fried up the sausage, bacon, egg, black pudding, and potato bread.

I slid the assemblage onto a plate and poured myself a big mug of strong, sweet coffee. This really was the breakfast of champions. I’d had it every morning of my life from about 1979–1986 in Carrickfergus, where all that fat and sugar and caffeine served as a barrier against the cold, wet Irish winters and the even colder, wetter Irish summers. With food like this, you could build a house or terraform Mars or write a novel or discover an unknown continent.

I sat down in front of the plate, unscrewed the top of the bottle of HP sauce, and took in the aroma for a second. I stabbed my fork into the first bit of potato bread, raised the bread to my mouth, and then, suddenly, I stopped.

When you’re a writer writing about 1980s Northern Ireland, you can occasionally venture into some scary waters. I’ve said things in my books that have upset people. Sometimes quite prominent people. Sometimes quite prominent people who used to be (and possibly still are) in charge of large terrorist organizations. I’ve also said a few negative things about British Intelligence, the RUC’s Special Branch, and the SAS. And they and their friends have said things back to me. I’ve had my share of troll attacks on twitter, and also those organised troll attacks on Amazon where they give your books 1-star reviews. It's not nice, but it goes with the territory.

When you’re a writer writing about 1980s Northern Ireland, you can occasionally venture into some scary waters. I’ve said things in my books that have upset people. Sometimes quite prominent people. Sometimes quite prominent people who used to be (and possibly still are) in charge of large terrorist organizations. I’ve also said a few negative things about British Intelligence, the RUC’s Special Branch, and the SAS. And they and their friends have said things back to me. I’ve had my share of troll attacks on twitter, and also those organised troll attacks on Amazon where they give your books 1-star reviews. It's not nice, but it goes with the territory.

I’ve also had a few slightly more disturbing incidents at book readings here and there. I’ve been heckled by Irish nationalists in Boston and Denver, and I had one unpleasant encounter with an Ulster Loyalist who accused me of using him as a model for a fictional character in one of my books (in all fairness he was right about that, but I didn’t admit it at the time). At another reading, an unhinged fellow said he “had a knife,” and I am friends with one prominent writer who was punched in the face by a “fan” at Bouchercon. To this day, of course, Salman Rushdie and his translators must travel with a police escort.

Voice in my head: look at you comparing yourself to Salman Rushdie indeed! You'd be lucky to get a fatwa. Fat arse more like.

But still, was it possible that through the vector of this sweet old lady and her potato bread, my online enemies were about to get their revenge? I mean who was this woman? I didn’t know her from Adam. The only thing I did know was that she had a heavy Belfast accent. She could be the great aunt of ******* ********* or ***** ********** or even ****** (Mad Dog) ******.

I looked at the potato bread. It seemed innocent enough—but it would wouldn’t it? As a mystery novelist, I knew that there were half-a-dozen poisons that were odorless and tasteless but which could kill you in minutes once ingested. You could make several of them from ingredients that could be bought at your nearest pharmacy. And it wouldn’t even have to be murder they were after. A strong, odorless laxative would teach me a lesson, too.

I put the fork down on the plate.

Wasn’t this all just a bit ridiculous though? I remember listening to the BBC’s Test Match Special on Radio 4 in the 1980s. Members of the public were always sending in homemade seed cakes, Dundee cakes, and buns, and those cricket commentators had no problem eating said cakes on the air and commenting on their moistness, zestiness, or other qualities. Shouldn’t I just have a little faith?

No, I decided, I shouldn’t. The provenance of the potato bread was questionable, and therefore the whole meal might be contaminated with, say, ricin.

I tipped the entire breakfast into the bin. What a crying shame, I thought. The chances of it actually being poisoned were probably about 10,000 to one. And, anyway, if it really had been poisoned, it might have been worth eating it just for the metaphor. What a poetic way for an Irish mystery novelist to die: poisoned potato bread; Jesus, the copy just writes itself. New York Times, front page, above the fold … but no.

My family probably would be upset. And the cat definitely would be put out—for at least half a day. When I picked up the kids from school, they asked me how the Ulster fry went. “Delicious,” I said. “You really missed out. Breakfast of champions.”

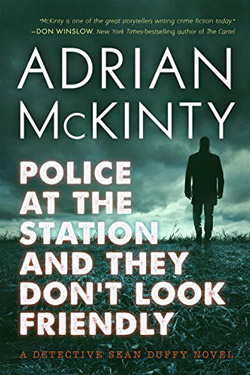

Read an excerpt from Police at the Station and They Don't Look Friendly!

To learn more or order a copy of Police at the Station and They Don't Look Friendly, visit:

Adrian McKinty is the author of eighteen novels, including the Detective Sean Duffy novels The Cold Cold Ground, I Hear the Sirens in the Street, In the Morning I'll Be Gone, Gun Street Girl, and Rain Dogs and the standalone historical The Sun Is God. Born and raised in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland, McKinty was called “the best of the new generation of Irish crime novelists” in the Glasgow Herald.

I love Sean Duffy!! I will be making Potato Farls for St. Patrick’s Day breakfast–no ricin!

I don’t know a farl from a ricin, but I’ve read all of Adrian McKinty’s books, including Police at the Station – no, that’s wrong, I’ve listened to all the books – and the only thing I can think of to enhance enjoyment of the books is Gerard Doyle’s narration. Thank you, Mr McKinty. I’m glad you didn’t take a chance with breakfast.

uzii คาสิโนออนไลน์

SexyPG1688 บาคาร่า เดโม่ เว็บออนไลน์ที่ให้ได้มากกว่า