A Question of Choice in Noir Fiction

By Gregory Galloway

October 12, 2021

Who’s in control of your life? You? Or someone or something else? It’s a heady question, asked about as long as humans have thought about anything, and it’s at the heart of crime fiction, especially noir.

Much of crime fiction is predicated on inevitability (chances are the detective is going to solve the case, order is restored, etc.) but noir fiction is as much an investigation into inevitability as it is the crimes. And it was there from the beginning.

From the minute twenty-four-year-old Frank Chambers gets thrown off the hay truck and winds up at the Twin Oaks Tavern at the beginning of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934), James M. Cain sets a nifty trap. Frank is looking for a new life, running from a dozen or so arrests in his past, and bluffing his way to a free meal, a job, and the boss’s wife. Frank might think he’s making his own choices, but Cain calls that idea into question, frequently asserting that Frank and Cora are not only bound by desire, but by fate. They are trapped by forces they don’t understand, and the minute they get what they want, they’re unhappy. Cora, like Frank, has left one life for another, marrying the “Greek” for stability and money, and then leaving him for Frank, always winding up wanting more, wanting to escape to something else. Whatever fleeting happiness they find, they soon wind up where they started, looking for the next thing, until fate catches up to them, even if it takes a couple of tries. The “Postman” of the title is frequently interpreted as a larger force at work, Death, Destiny, or Fate, something inevitable that comes for everyone in the end.

Secret forces at work is also a theme of Dashiell Hammett, from criminal organizations to the world itself as a great machine with “works” few of us get to see. For Hammett, the world can’t make sense because we are incapable of seeing how it really works. It’s no wonder that Albert Camus was a fan of James M. Cain and Jean-Paul Sartre loved Dashiell Hammett. Camus used Cain’s first-person confessional style of Postman as his model for The Stranger (1942), and Sartre supposedly had Dashiell Hammett in mind while writing Nausea (1938), one of the seminal existentialist writings. In an absurd world, the existentialists said, all we have is our own conduct. It’s a concept Sam Spade would have agreed with, or Philip Marlowe, who sees himself as a knight in a corrupt world that no longer has any use for knights. Spade has integrity because he’s “supposed” to as a detective, but Marlowe has integrity because it’s the only way to live. Sartre would agree with Marlowe and Spade, and all would agree with the misanthropic philosopher Heraclitus, who said, “Man’s character is his fate.”

In The Maltese Falcon (1930), Sam Spade talks about a case involving a man named Flitcraft, who had disappeared from his wife and life in Tacoma. Flitcraft, however, was alive and well in Spokane; he had fled his old life after a near-death encounter caused him to examine what the hell he was doing (the experience lets him get a glimpse at the “works,” Spade says. “The life he knew was a clean orderly sane responsible affair. Now a falling beam had shown him that life was fundamentally none of these things.”). So he drops everything to try and start a new life. According to Spade, the trouble was that Flitcraft’s new life in Spokane was almost exactly like the one he’d left behind in Tacoma, same sort of job, same sort of wife. Changing his environment hadn’t changed his choices at all. “I don’t think he even knew he had settled back into the same groove,” Hammett writes.

“Out here you’re a man, a man and a gentleman, or you aren’t anything,” Lou Ford says in The Killer Inside Me (1952) by Jim Thompson. Thompson, in true noir fashion, takes Marlowe’s integrity and turns it inside out. Not only does the world no longer need knights, it won’t allow them. Lou Ford can’t be a gentleman, a good cop, and good guy (he’s dating his childhood sweetheart, now a schoolteacher) because his true character is that of a sadistic psychopath. Ford’s good guy pretense quickly slips, unleashing the “disease” that he’s tried to control. Leading a double life is tough.

Tom Ripley takes on a new personality almost as easily as he puts on a different shirt (or Dickie Greenleaf’s ring), and while he can change identities, partners, towns, he ultimately can’t escape himself. While Ripley is not caught at the end of The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955), and seems to be living the lavish life he always wanted, real or imaginary forces seem to be closing in on him. He thinks he sees policemen waiting for him on an “imaginary pier,” and wonders if he’ll begin to see policemen everywhere. “No use spoiling his trip worrying about imaginary policeman,” he tells himself, but Highsmith hints that Ripley’s paranoia is only beginning.

And if you want to get farther away from the integrity of Marlowe, take The Burglar (1953) by David Goodis, where everyone is a “criminal, and every move in life is a part of the vast process of crime.” Nat Harbin has been a thief for eighteen years, without ever getting caught, and decides to leave his life and his criminal family behind. The “vast process of crime” has different plans for Harbin, however, and Goodis frequently reminds the reader that Harbin’s fate was sealed long ago, when he was saved by a mentor who taught him how to be a thief, and little else.

Harbin can’t change any more than George Stroud can in The Big Clock (1946) by Kenneth Fearing, where identity, fate, chaos, and corruption are in full force. Stroud (editor of Crimeways magazine, just one more job after a long list of them, including timekeeper) witnesses his boss murder their shared girlfriend and is then put in charge of finding the witness so his boss can pin the murder on him. He’s a man literally searching for his own identity. And when his boss discovers that the witness is in the building and begins to systematically isolate him, the forces of inevitability are seemingly set into motion. Fearing is not shy about the symbolism. “This gigantic watch that fixes order and establishes the pattern for chaos itself,” Fearing writes: “it has never changed, it will never change, or be changed.” While much of crime fiction is told in single first-person, Fearing uses multiple narrators to circle the action, cogs in a machine that turns and grinds away as George Stroud is closer and closer to being discovered. It’s a familiar road by this time, but Fearing has a few surprises (especially for 1946) and a unique way of telling the story.

All roads in crime fiction, at least for me, inevitably (see how it happens?) lead to a George V. Higgins novel. But maybe not the one you’re thinking. In the sincerely/ironically titled Trust (1989), ex-con Earl Beale trusts his brother, who asks him to do a job for another man. “I’m not gonna do this,” Beale says. “I don’t know what I’m doing. I don’t know who I’m doing it for.” But Beale doesn’t have a choice. “Didn’t you ever start to think: ‘How did I get here?’” his girlfriend asks. For Beale, the answer is an easy no. He doesn’t ask questions, he just acts. Beale sees every situation as a scam—whether it’s selling cars, stealing cars, blackmailing his prostitute girlfriend’s client, or worse—and trusts himself to come out on top. “If Earl’s doing something, Earl will get caught,” his brother says, but Earl Beale just keeps barreling down the same road, thinking he’ll wind up someplace different.

“As though a moment comes when it’s both necessary and natural to make a decision that has long since been made,” Georges Simenon writes in Dirty Snow (La Neige était sale, 1948), and while Simenon might be best known for his detective Jules Maigret, he also wrote a number of “hard novels” (“roman durs”), noirs that epitomize isolation, alienation, and characters trapped by fate. La Veuve Couderc (translated as The Widow) was published the same year as Camus’ The Stranger, and deals with many of the same themes, as well as echoing The Postman Always Rings Twice. Jean is fresh out of prison (haunted by the fact that he was not put to death for a murder he committed, and has been released due to legal technicalities and shady maneuverings) and literally at a crossroads looking for a new life, before hooking up with the widow, Tati Courdec, who runs a farm and “needs” Jean from the moment she sees him. Jean believes that if he can find a home, he can find peace and settles into what should be a comfortable life, but soon gets involved in a love triangle (or maybe even a quadrangle) and his escape quickly becomes a prison. Jean is obsessed with his past, which inevitably becomes his future. “He waited for what could not fail to happen” Simenon writes, which is about as succinct a description of much of crime fiction as you can get.

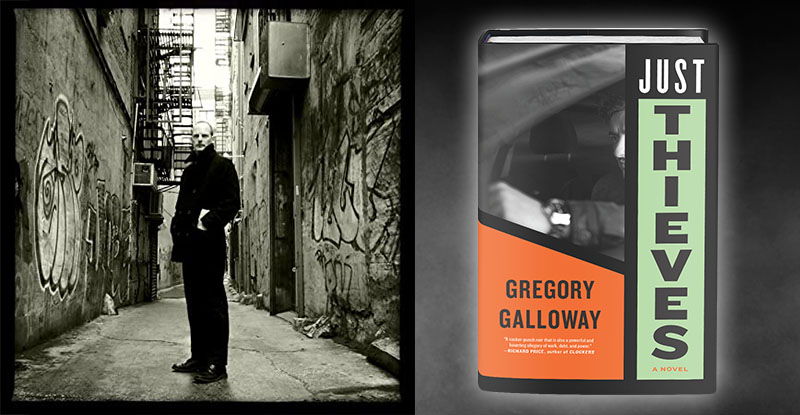

These novels (and many more) inspired and informed my writing life. I have read them and studied them. Maybe I was destined to write Just Thieves, about a pair of burglars who think they’ve got everything figured out, but are caught in a trap they can’t see. They are controlled by their pasts, their characters, and their choices. They know the world is a machine, but can’t quite get the lid off it to look at the works. I’ve tried to add to the tradition (with some obvious and not-so-obvious nods here and there), tried to bring a new perspective to the old questions.

Maybe now you’ll go re-visit an old novel, or introduce yourself to a new one. It’s your choice, isn’t it?

About Just Thieves by Greg Galloway:

Comments are closed.

Gracias por la información que aportas a quienes andamos a la búsqueda de aprendizaje útil como el que has expuesto!!

Really very happy to say, your post is very interesting to read.I never stop myself to say something about it You’re doing a great job. Keep it up

Love this book. Great work.