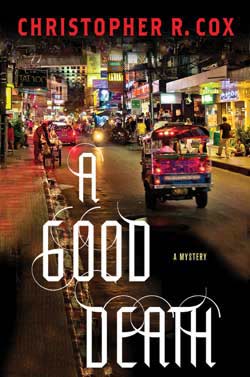

An excerpt of A Good Death the debut novel from Christopher R. Cox (available February 19, 2013).

An excerpt of A Good Death the debut novel from Christopher R. Cox (available February 19, 2013).

Linda Watts is a beautiful, talented Southeast Asian refugee with a promising career in finance—or she was, until she turned up dead, the victim of a heroin OD, in a cheap Bangkok guest house. Her death seemed straightforward to the Thai authorities, but her insurance company isn’t buying it. They send Boston PI Sebastian Damon halfway around the world to investigate—where he finds himself confounded and completely out of place chasing faint leads through the broken, bewildering streets of Thailand’s teeming capital.

Chapter 1

Somewhere between the airport and downtown, in the steamy, sinking warren of Bangkok’s broken streets and stinking canals, my taxi driver began complaining. Loudly. Four hundred baht had seemed a fine fare when I slumped into his dented Toyota sedan after midnight, but now he found the thirteen-dollar amount wanting. He thought seven hundred baht a better price for a foreigner to pay. Farang always paid more. Why wouldn’t I pay more? So he had left the airport expressway, haggling while he sped along a secondary road, scattering stray dogs that had come to forage on heaps of trash beneath the faint street lighting. The Grand Babylon Hotel was nowhere in sight. Around me the night stretched away, black and molten. The moonlit reflection of rice paddies, perhaps. I had no idea where I was or where we were headed. Cambodia or Burma didn’t seem out of the question.

“First we go to Patpong,” he insisted. “Buy beer. Buy Thai lady massage.” He pumped his fist, cackling. “Good lady make you forget bad airplane. Then we go to hotel.”

He pounded the steering wheel and, without slowing the car, turned to judge my reaction. His grin was an uneven stream of silver fillings, his eyes just dark, speed-dilated pools. “For you,” he said, “six hundred baht. Special price.”

Now we were getting somewhere.

“Four hundred,” I said evenly.

He moaned; the cab accelerated. We vaulted a short, arched bridge over a dank creek. Then we abandoned paved roads for a muddy lane through a slum of lean-to shanties.

“Patpong,” he insisted. “We go Patpong. For you, six hundred baht.”

I quietly unlocked the back doors, checked my pockets. Wallet. Passport. Tickets. Thai phrase book. Swiss Army knife? Inside my suitcase, which was rattling around inside the trunk of the taxi. Not good. I scanned the brooding night for clues of my whereabouts. Less than an hour after landing in Thailand, it looked like I might get rolled in the middle of nowhere.

“Forget Patpong,” I said. “Take me to the Grand Babylon. Sukhumvit Road. I’ll pay you five hundred baht. No more.”

Exhaustion gnawed at the edges of my patience. I hadn’t slept the entire flight. I felt dulled, devoid of ideas, with a screaming headache—the consequence of a recent on-the-job injury—scouring my skull. Hardly the condition required to nail this case. I had less than a week to find my subject—if she was still in Thailand. If she was still alive. I needed to get to the hotel and then check in with my client. It was after midnight local time, so it had to be around lunchtime back in Boston. A lot can happen in the thirty hours it takes to fly from Boston to Chicago to Tokyo to Bangkok. Given its current meltdown, the Thai baht had probably plummeted another 10 percent against the dollar. I owed another day’s compounded interest on my mounting bills. And my subject had more precious time to deepen the mystery of her whereabouts.

The driver clucked and unleashed a stream of Thai invective, no doubt agitated by the kingdom’s economic predicament and the cheap-bastard American customer sprawled across his backseat. He pulled a few g-force turns on rutted tracks, accelerating to scatter mud, trash, and chickens until we finally emerged onto a divided six-lane thoroughfare still crowded with traffic at . . . who knew what hour it was? I had forgotten to set my watch to local time. But it now had to be after one o’clock in the morning. My disoriented system craved a turkey club sandwich.

“Sukhumvit,” he pronounced.

I rolled down a back window and drank in the stew of internal combustion and infernal temperatures. In the distance, thunder groaned like a hospice patient. Thailand didn’t waste time. As soon as you arrived, it plunged you into its labyrinth of heat and intrigue, scents and secrets, traffic and lies. Hard to believe that just a day ago I had held all the trump cards. I knew the streets. I spoke the language. Best of all, I understood the people. I sensed their motivations, mined their frailties, capitalized on their vanities. I’d had the knack as a reporter; the talent now also served me as a private investigator. I had always enjoyed the chase: the paper trails, the clandestine stakeouts, even the cold-call inquisitions. I had pulled surveillance in darkened cars and smoky bars, nursed cold coffee and warm beer for hours, watched and waited while crooked businessmen and cheating husbands discarded their careers and discounted their marriages. Once, I had done it for the story. And now, since the news business had betrayed me, I did it for the money.

The promise of the first decent check in months had brought me to Bangkok to chase Linda Watts. With any luck the case might also put my new career on the fast track, above the usual PI drudgery of matrimonial investigations and workmen’s-comp claims. Had I known my subject when I was writing for the Ridgefield Beacon, I might have given Watts’s life the long, heartwarming feature treatment. She had been born in an uncharted village in Laos, a country few Americans could even find on a map. What notoriety Laos had achieved came from the dubious distinction of being the most heavily bombed country in the history of warfare—this despite the fact that it was officially neutral during the conflict in neighboring Vietnam. Linda had fled this carnage not long after the Communist victory in 1975 and spent half a decade in a grim Thai refugee camp. She had come to America with her uncle, her sole surviving relative, in 1980. In the States, hers was the quintessential immigrant success story: a welfare childhood in California, Minnesota, and finally Rhode Island, accented by academic excellence. That performance had earned Linda Watts a full scholarship to Boston College, where she had graduated cum laude in finance. She had then taken a job with BankBoston and begun a steady rise through the ranks—loan officer, assistant vice president—ascending a year ago to the position of vice president in the firm’s small-business-lending area.

But her life had recently gone off-track in perplexing ways, which explained why I was riding through Bangkok’s darkest, outermost limits in a taxi driven by a methamphetamine-addled maniac. In April, just three months earlier, Linda Watts had broken off her engagement. A month later she had gone to Thailand on vacation. Then, in mid-June, her body had been found in a cheap guest house in a gritty part of Bangkok favored by backpackers and budget travelers. The official cause of death: a massive heroin overdose. She was just twenty-eight years old, according to her records, which seemed part of the mystery as well. Her age was just an estimate. No one kept vital statistics in the distant reaches of the Annamite Mountains, where Linda Watts had been delivered into a violent, primeval world.

A Bangkok OD had not been the news anyone expected; it certainly wasn’t what my client wanted to hear. The Cotton Mather Mutual Life Insurance Company stood to lose several hundred thousand dollars settling Watts’s life-insurance policy and the claims department manager was having none of it. She had told me as much: the timing and circumstances of Linda Watts’s death were highly suspicious. The two-year contestable period on Watts’s original policy—$250,000 face, $500,000 with the double indemnity—had barely passed. Then there was the conflicting association of traits: bankers, especially achievement-oriented immigrant bankers, were sober, cautious people, she argued, not mainlining junkies.

Linda Watts was not dead, my client said flatly.

But where was she, then? Mather Mutual had paid me to find out, and quickly. I had the company’s thin case file as guidance: a few Thai documents, her original life- insurance application form, an old photograph. I could make little sense of the Thai-language papers; I had yet to tire of looking at her picture. Linda Watts was striking, even within the confines of a college-graduation portrait: copper skin and high cheekbones, wide mouth and pillowed lips, startling blue-gray eyes and auburn hair tumbling over her shoulders in thick waves. She looked more Native American—Apache perhaps—than Asian, which only added to her mystery. More than her appearance, however, something about her solemn attitude haunted me. That college photograph should have reflected one of the greatest achievements of her remarkable life, yet she looked as if she had just been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Was she out there, a wan face in a land of smiles, daring me to find her? Knowing I didn’t have much time?

We drove in silence for a few miles, then the taxi driver resumed complaining.

“Please, sir. Five hundred baht, no profit. Why not more? Why not six hundred?”

He shifted to a curbside lane, as if to exit and make another off-road sales pitch.

“Six hundred,” I said wearily. “Now shut up and drive. But to my hotel. No Patpong.”

What was another few dollars to a client like Mather Mutual? I didn’t know it then, but I had lost the first of many rounds with Thailand.

I lay back on the overpadded rear seat and fought the urge to sleep, to surrender to an emptiness beyond dreams. The driver hummed happily as we moved along Sukhumvit Road, a major thoroughfare lined by a bulwark of small office buildings, retail shops, and hotels that stretched into the night for miles. I struggled to formulate a plan of action for the coming day—U.S. embassy, Bangkok medical examiner, Thai immigration—but kept dozing off. The driver finally turned onto a narrow lane between two office blocks, swung around a dry, shattered fountain that had claimed less-alert hacks, and skidded to a stop in front of the Grand Babylon Hotel. I counted out his precious six hundred baht and lurched into the spacious, silent lobby. My artless entrance roused the slumbering night manager at the reception desk, but not the hotel’s overnight security—a uniformed Royal Thai Police patrolman—dozing blissfully on a teakwood bench next to the elevator.

After the manager slowly copied out the details of my passport, a drowsy bellboy appeared from a back room. We rode a cramped elevator that smelled of ammonia to my third-floor room, where he demonstrated the disappointing amenities: harsh lighting, basic-cable television, plastic telephone, tiny minibar. So much for the veracity of the guidebook I’d relied on to select this “business friendly” hotel. With a tip-hungry flourish, he opened a sliding glass door to a narrow balcony. I stood at the threshold, felt the greasy night seep into the cool room. The boy pointed across the traffic circle to a building identical to the Grand Babylon but for a flocking of black mold on its walls and Crayola-colored lingerie fl uttering like erotic semaphore signals from scores of balconies.

“Maybe you like lady massage?” the bellhop asked. He grinned, the expectant pimp.

I felt like a long-distance runner who had begun his finishing kick far too soon and now staggered painfully down the last, interminable stretch to the finish line. Waves of fatigue pummeled my body, eroded my thoughts. Mather Mutual, Linda Watts, Thai ladies—they all would have to wait. I gave the boy a crisp, new fifty-baht note and called it a night.

Chapter 2

I didn’t awake until midmorning, when the thick fug enveloping the room and the dull hurt across my face goaded me from a bed that reeked of recent, purchased lust. Still stiff from more than a day in economy-class seating, I slowly stepped onto the terrace and regarded the city. Its scent was at once ancient and industrial: charcoal smoke and spoiled fruit, diesel fumes and wet concrete. Although a putty-gray scrim of smog filtered the morning sky, my bruised left eye still caused me to squint to try to make sense of this chaotic, corrupt capital. Good news had rarely been contained in any story I’d ever read with a Bangkok dateline—a litany of fires in sweatshop factories, floodwaters in the streets, illegal wildlife on restaurant menus.

This had all started with an irate husband. I made my living chronicling the disintegration of marriages, and Porter Moyle should have been an easy fee, even on short notice: a corporate lawyer having a midlife crisis on an out-of-town business trip. It didn’t get more obvious. My client, Dolores Moyle, had rung me about nine o’clock on a Sunday night, a little more than a week earlier, while her husband was in the shower. I was still at the office. Hell, I’d been living at the office, the middle floor of a three-decker in Somerville’s Union Square, since Christmas. Ever since Dianne had finally left me. At that hour it was too late to arrange for any operatives to back me up in Washington, D.C., where Porter Moyle was heading the following morning. I took the case anyway. I needed the work.

It had been barely a year since I had quit the Beacon, after the managing editor killed a project I’d labored over for weeks. There was absolutely nothing wrong with the story except that the main subject—an ethics-challenged real-estate developer—happened to golf in my publisher’s regular Friday-morning foursome. My investigation wouldn’t do, especially in a clubby Connecticut town like Ridgefield. So I sent the story to the nearest competition, a daily in Danbury, and cleared out my desk even though I didn’t have the fuck-you money to cushion the abrupt shock of unemployment. When my subsequent job search went nowhere, my father had grudgingly taken me aboard his one-man firm. And a strange thing happened: I found that I liked detective work, could even endure close quarters with the old man. I enjoyed seeing my name on the letterhead of Damon & Son Investigations nearly as much as I had seeing my byline attached to a page-one story. But my wife had worshipped Connecticut. Dianne hated my new line of work, my unpredictable hours, and especially our shabby, urban address, which was nowhere near Harvard Square, let alone Central Square, in Cambridge. Too unseemly, she sniped, rummaging through other people’s secrets. It was bad enough working as a poorly paid reporter and chasing small-town news. As a private investigator, she complained, I’d become a full-blown cynic. She left me with a five-figure Visa bill and went back to grooming the dogs of Fairfield County’s rich and dysfunctional. I knew nothing about love, she said. She was right, as always. And, working matrimonial cases, I never would.

I had made the subject at Logan the next morning among the herd of suits awaiting the eight o’clock shuttle to Washington. At fifty-two, Porter Moyle pushed six feet two inches and 240 pounds and wore his thinning, graying hair long, well over the collar of his khaki summer suit. He had the look of an old tight end gone soft, relegated to golf with clients and the odd game of squash. I placed his stylishly dressed companion—about five feet six, Mediterranean complexion, with the carriage of a club-level tennis player—in her early thirties. She had come to the gate ten minutes after Moyle. I went back to reading the Herald. There was plenty of hand-wringing about the impending Hong Kong handover and the sunset of the British empire. Mike Tyson was getting eviscerated in the press for biting Evander Holyfield’s ear during Saturday’s fight. And the Red Sox were swooning again, already fifteen games back of the Orioles.

Moyle and his mistress had played it coy in Boston, with no interaction in the crowded lounge, and boarded the plane separately. Once we were airborne, however, their party began. It was easy enough to get video with the matchbox-size pinhole camera concealed inside the Red Sox windbreaker I wore. The camera was a beauty: a ninety-degree viewing angle, low-lux rating, and excellent picture quality. The couple sat three rows behind me and I just stood in the aisle, pretended to secure my bag in the overhead luggage bin, then walked past them to the bathroom. Guys like Moyle always got sloppy out of town. Deluded by lust, arrogance, and a few Bloody Marys, he made my job easier. He had forgotten a cardinal rule of infidelity: never allow yourself to be seen in public with your tongue in the ear of a woman who is not your wife.

When we landed at National Airport, I tagged the couple into town in another cab. Porter Moyle avoided the quaint romance of a Georgetown bed-and-breakfast for the Willard InterContinental, a beaux arts pile two blocks east of the White House favored by politicians, potentates, and law-firm partners out to impress their girlfriends. The rascals and the cheaters always stayed in the best places. After the subject had registered, I asked the receptionist for the next- door room on the eighth floor. Twenty dollars convinced him I wasn’t a jumper. Moyle and his mistress were already in the sack by the time I hooked up my microcassette recorder and stuck it to the shared wall with a suction microphone. They carried on in impressive fashion, much longer than the normal, adulterous three-minute rutting. Then I heard another set of aroused voices. It took a few moments of theatrical sex talk before it dawned on me: Porter Moyle had rented some soft-core porn flick on Spectravision. The interlude seemed a good time to check in with Dolores Moyle. Her secretary answered and put me on hold until my client had wrapped up a conference call.

“How bad is it?”

It was Dolores Moyle’s style to cut right to the chase. She already knew the truth. Most spouses do by the time they come to me.

“Your husband met another woman at Logan, and then flew here with her. They just checked into the Willard.”

“Where we honeymooned,” she said, as if surprised by this insult.

“I photographed them together on the flight. I also have pictures of them in the lobby here. And I recorded some compromising dialogue.”

I didn’t have the heart to tell her how compromising.

“Take a room if you have to. Try 815. Nice views.”

“That room’s already occupied. I’m sorry.”

“Get everything you can,” she said, her voice filling with cold fury. “Everything.”

Porter Moyle had made a very costly mistake. I hoped he had deep pockets. A decent attack-dog divorce attorney could use this evidence—photographs, recordings, tickets, receipts—to establish, in devastating detail, the continuity of an affair. It always ended badly for cheating husbands, if the PI was any good.

After my client hung up, I went downstairs and hired a taxi outside the Willard for a flat half-day rate. The old man had taught me that hailing cabs piecemeal while on surveillance was too risky and conspicuous, while renting a car for an urban situation invariably meant parking problems. I got into the cab, and waited. When Moyle appeared fifteen minutes later he wore a fresh blue dress shirt with his suit and the smug aura of a man who has just indulged in vigorous, illicit sex. I tailed him over to K Street, the business after his pleasure, and watched him disappear into one of the interchangeable buildings along the steel-and-glass gulch that was prime habitat for lobbyists and corporate lawyers. The buttoned-down kind of place where I might have worked had I taken my mother’s advice and gone to law school instead of running away to Europe after college.

An hour later, Moyle reappeared and took a cab north into Adams Morgan, a funky neighborhood of ethnic markets and restaurants. The woman waited at the sidewalk table of an Ethiopian restaurant—probably her idea, gleaned from a glossy travel magazine. Moyle seemed like a steak-tips-and-fries kind of guy. The couple ate with their hands, scooping food with clumps of flat bread. Soon they were nibbling the slop off each other’s fingers. I knew where this was leading: back to the Willard. I quickly wearied of taping their afternoon- delight orgasms. It was deflating, the prevalence and predictability of infidelity. I couldn’t remember a matrimonial case where I hadn’t gotten the goods on a subject; there had never been any relief or reassurance that a spouse was absolutely clean. They had all cheated. They invariably treated their lovers with more passion and consideration than their partners. And consequently, they all got crushed in divorce settlements. Small wonder Dianne considered me such a cynic on the subject of long-term love, or that I had since shied away from any sort of relationship, even casual, personal-ads dating, after she filed for divorce. Narcissism and infatuation steeped the sordid world I worked in; my profession held no proof, no affirmation of trust or commitment.

I went downstairs to the hotel lobby, found a wing chair by a sunny window, and settled in for the duration. I don’t know how long I’d been dozing before someone was shaking my shoulders, commanding me to wake up. Standing over me was a woman in her late forties, wearing a dark-gray power-suit ensemble. The sandpaper-and-honey voice ordering me to snap out of it could belong to only one person. My client.

“The concierge kindly pointed you out. Is your nap rate the same as your day rate?”

“The subject— your husband— went upstairs a few minutes ago,” I bluffed.

“Then we have time to talk. I suppose there’s a lot to catch up on since we spoke this morning.”

“This isn’t a good idea.”

“Nonsense. It’s my marriage.”

“I’ll have to break off surveillance. A confrontation could jeopardize your case.”

She glared at me.

“I’ll make the decisions.”

“You’re paying for my expertise as well as my time, Mrs. Moyle. Your presence here won’t help.”

She didn’t budge. An elevator settled and opened its doors. Porter Moyle stepped into the lobby and into his wife’s view. Too late.

“Dolores,” he said, clearly shocked. “What a nice surprise.”

He walked over, arms extended as if ready to embrace his wife.

“The Willard, Porter? You little shit.”

Break it off. Don’t let it heat up. Avoid a confrontation.

“Who’s it this time?” she persisted. “Another paralegal? A waitress?”

“I’ve been in meetings all day. What are you talking about?” He turned those broad shoulders my way. I probably gave away three inches and at least sixty pounds. “Who’s this lungfish?”

He studied us, trying to place me. It took a few seconds before his glib, defensive smile disappeared and the color drained from his face. He remembered. Logan Airport. The shuttle. The lobby. Lunch.

“What’re you trying to prove, Dolores?”

“What do you think you’re hiding, Porter?”

Porter Moyle gave me an accusing look.

“You’ve been following me around all day.”

“I just met the lady in the lobby.”

“Bullshit. You’ve been bird-dogging me since Boston.”

“I’m just down here on business, sir.”

He moved closer, as if sizing me up for a clothesline tackle.

“What kind of man follows other men around? You get off on stalking me?”

“For a man in a khaki suit, you’ve got a very vivid imagination.”

“You screwing my wife, too? The two of you up to something?”

“Shut up, Porter,” Mrs. Moyle hissed. “You’re the only dog here.”

She took a step toward her husband, swung, and missed with an open-palm slap. I turned toward her, trying to figure a way to play this scene. I never gave up a client. I never compromised an investigation. And I never saw Porter Moyle’s round house punch whistling toward my face.

At least the blowout fracture had been a boon for my business. On Wednesday afternoon, two days after the confrontation at the Willard, Dolores Moyle had walked into my office and offered me another, better case. I wouldn’t have to tail her husband anymore; she had filed for divorce. She felt indebted to me for my work and for my facial injuries. She wanted to alleviate my pain, she said, to supplement the Percocet with a well-paying assignment. The job she proposed wasn’t a domestic case, not even workmen’s comp. It was better, far better: overseas life-insurance fraud. As head of the claims department for the Cotton Mather Mutual Insurance Company, Dolores Moyle had the authority to retain any investigator she deemed fit. She was going to make me forget all about Washington, D.C., and the Willard punch-out. She wanted to send me off to look into a very suspect claim. Big-game hunting, she called it. The quarry was a young woman with questionable intentions.

Over the years, Dolores Moyle recounted, she had used my father’s firm for a few disability jobs; he had always delivered thorough, professional work-ups. But, aside from following her husband to D.C. and getting my lights punched out, I was an unknown quantity. And to her way of thinking, the Watts case already presented enough unknowns. She paused to light a menthol cigarette with a flourish that indicated: Tell me about yourself. I waited for the infernal wail that signaled a run from the nearby fire house to subside. Then I sketched my background: college in North Carolina on an athletic scholarship, an English degree. Journalism school had been out of the question—I couldn’t pass the minimum forty-five words per minute on the typing test—so I’d majored in Conrad, Hardy, and Kipling. Then I told her how I had come to join my father’s firm, passing up law school for several summers on the European running circuit, followed by a succession of dead-end jobs—proofreader, technical editor—that culminated in my job at the Beacon. While I didn’t have a journalism-school diploma, I had several compelling qualifications: I could string together a few coherent sentences; I would work for virtually nothing; and although I typed slowly, my copy was clean. And the Beacon editor was a friend of an old college teammate of mine. That had landed me a job as an entry-level general-assignment reporter. Then, all I’d had to do was not screw up too badly while covering the endless meetings that were the staple of small-town news, and keep my own name out of the local police blotter.

“Any experience beyond matrimonial investigations?”

“Plenty: security checks, disability and workmen’s comp, missing persons.”

These were a detective’s staples. The work was fairly routine and the clients always paid the bill. Furthermore, they didn’t materialize in luxury-hotel lobbies and compromise an investigation.

“I’ve also done workups, pretext calls, canvassed neighbors and relatives, checked financial records, checked criminal records, checked court records, run stakeouts. Anything else, I’m a quick study.”

“Any military service?”

“I didn’t go into that family business.”

It only seemed like I had served. As a kid, practically every year had meant moving to a new army base and enrolling in a new school, but always the same cheerless dependent housing and lousy, understocked PXs.

“And where is the illustrious Sergeant Damon these days? It surprised me when you answered the phone instead.”

“Retired to Florida a few months ago. He’s the dockmaster at a marina down on the Intracoastal Canal. He’s living the Parrot Head dream: got a thirty-eight-foot Chris-Craft and a forty-year-old girlfriend.”

“An army lifer with a boat?”

“Dry land didn’t treat him very well.”

“He also had police experience. You?”

“I was a mall cop one Christmas.”

“I’ll take that as a no.”

I spoke about my contacts within the Boston Police Department, the Massachusetts State Police, even the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Drug Enforcement Administration. I had retained my father’s sources. Many of these lawmen had served in the military, too, and that bond had carried over into cop life. After three tours in Southeast Asia and my mother’s ultimatum, Master Sergeant Thomas Jackson “Stonewall” Damon had finally packed it in and used his service connections to get onto the force in Boston. He loved the action, loved being a cop. The only drawback to civilian life, he once told me, was not being able to call in air strikes. But his police career had foundered after he collared a politically wired gangster holding a gym bag full of cash and a one-way ticket to Honduras. Despite pressure from police headquarters and, by extension, city hall, he had refused to make the arrest go away. So when he began getting passed over for promotion, he turned in the badge, got a PI license, and began playing his web of contacts.

“Are you familiar with life- insurance policies?”

“I don’t have one yet.”

“You really ought to consider it. At your age, it’s still very affordable.”

“Maybe when there are people who depend on me.”

“I’m asking you all this, Sebastian, because I have a serious overseas case.”

“I’ve spent some time abroad. And I’ve worked enough insurance investigations.”

“This won’t be a European vacation, or workmen’s comp fraud. What do you know about Thailand?”

“Pretty mountains, prettier beaches. The military coups are usually bloodless. Their currency, the baht, is about to go in the toilet. Monsoon season should be starting soon. So I will have to move fast if you want me on this case. Before the deluge begins.”

And that’s when she told me about Linda Watts, the particulars of her American odyssey and the peculiarities of her Asian death. An uncle, Bounliep Yanglong, who lived in Providence, Rhode Island, and was listed as the policy beneficiary, had just put in a half-million-dollar claim. Moyle handed me a manila folder containing several official- looking documents. There was a copy of Watts’s original life-insurance policy as well as paperwork submitted by her uncle. Beneficiary claim form. Coroner’s report. Death certificate. Cremation certificate. I reviewed them quickly. Most of the proofs were incomprehensible, written in the graceful, looping characters of the Thai language. The American embassy in Bangkok had yet to send its completed form, the “Report of the Death of an American Citizen Abroad,” but Mrs. Moyle doubted this last document would shed any new light. The State Department paperwork was invariably an English-language regurgitation of the official foreign story, she said.

I pressed her for further details about the death of Linda Watts.

“Alleged death,” she immediately corrected me. “Work on your skepticism, please. Two weeks ago the Bangkok police were called to a guest house in a part of town favored by the backpacker crowd. You know: the trekkers, the dopers, the burnouts.”

I knew the type. During my time running in Europe, I had seen them in cafés and vegetarian restaurants, clad in ethnic textiles and flaunting indigenous tattoos, nattering on about Goa and Morocco, giving righteous attitude to package tourists. Dolores Moyle, who had the taut physique of a serious jogger, wanted to know a bit more about my track career as a “rabbit.” I’d been a pacesetter in Europe, I explained, hired by meet promoters to push more elite middle-distance runners to faster performances, especially in the mile or the fifteen hundred meters. Spectators didn’t pay to watch tactical races; they wanted to see record-setting times. Rabbits ran too hard too early to have any hope of winning, however. We dropped out of the race, our work done, long before the bell lap. Malmö, Zurich, Brussels. It was decent money, with less training and pressure than in college, and left plenty of time for a languid Grand Tour. There were far worse ways to spend postgraduate life than running a few laps on a long, warm midsummer evening in a beautiful, historic city once or twice a week.

She considered these details.

“I need someone who won’t quit. Someone who won’t be satisfied just to have a payday.”

“That won’t be a problem,” I assured her.

“The Thai authorities say Linda Watts’s body was found after another lodger complained of the smell. They had to break down the door to her room. Dead nearly a day. Syringe still in her left arm. The body had already started bloating and rodents had made a mess of the soft facial tissue. The police confirmed the identity of the body from her passport. So did the American consul. The U.S. embassy notifi ed the uncle in Providence. He had her cremated at a Buddhist temple in Bangkok.”

I glanced at the file. The official evidence had failed to sway Dolores Moyle.

“The woman was a banker, not a waitress in a bike-messenger bar,” she continued. “Linda Watts didn’t dye her hair purple, pierce her nipples, or brand her arms. She earned more than sixty thousand dollars a year, plus an annual bonus. She had a quarter-million-dollar term life-insurance policy. And three months ago she added ADB, an accidental-death benefit.

“The double indemnity boosted her payout to five hundred thousand dollars. She also changed the beneficiary from her fiancé to her uncle, her closest next of kin. I love my uncle, too, but I’m not setting him up for life when I die. And then she goes to Bangkok and ODs? She didn’t think this through. A drug overdose makes the ADB contestable. And if this isn’t an OD, maybe we have a suicide on our hands. Was she despondent? You need to make absolutely sure Linda Watts really died, and died from an OD, before we cut the check. See if she’s done a buildup, too. Maybe she’s taken out small policies with other firms as well, hoping to run the same insurance scam. I don’t want Mather to cough up a goddamn dime that we don’t have to. This is not a good death. My gut says the whole case stinks.”

Mrs. Moyle had a bullshit detector for shady claims and it had gone off hundreds of times during her career. It’s why she now occupied a corner office in Mather Mutual’s Back Bay headquarters. Thailand made her suspicious, she said, although it couldn’t compare to ethical cesspools such as Nigeria, Haiti, or the Philippines. Life-insurance fraud had become a Third World growth industry. Government officials were pliable. Official documents were for sale. Accidents were frequent. And insurance companies were too lax. Mrs. Moyle launched into a spiel she had probably delivered at more than a few industry conventions:

“We’re part of the problem. Companies leave themselves wide open. Underwriting standards are far too liberal. Premiums are at least ten percent higher because of these scams. We rely on brokers and forget that the applicants—not the insurance companies—are their clients. The brokers write policies they shouldn’t write and we pay out on claims we shouldn’t pay. Our accountants figure that paying up is cheaper than hiring investigators to look into borderline cases. And most companies evaluate these claims the wrong way. They put their least-experienced adjusters on the smallest claims. But a lot of the fraud is on the one-hundred- or two-hundred-thousand-dollar policies. That may be short money over here but it’s a small fortune in a dump like Lagos or Port-au-Prince or Manila. I make sure my adjusters look at the cases, not the amounts.”

“If she’s alive, I’ll find her.”

“She’s alive. The facts say otherwise, but paperwork has a nasty habit of hiding the truth. You find this woman. Quickly. Personal injury attorneys love to get involved in these cases, toss around threats of punitive damages. All the pain and suffering to their clients caused by our heartless delays. Any day now her grieving uncle will retain a lawyer.”

“I’ll need a letter of authorization from the uncle before I can start pulling documents.”

“In the file.”

“Then everything would seem to be in order. About my fee . . .”

“I hope it’s in the same neighborhood as the Washington job.”

“It’s a more distant neighborhood—and it could get even rougher. I’d like to do a workup here on the subject: interview the insurance agent, the uncle, co-workers, significant friends. Let’s say two days here, a maximum of five days overseas. My Stateside rate is five hundred dollars for an eight-hour day. Overseas, it’s eight hundred.”

What did I know? I had never caught an international case and simply threw out a number.

“That’s five thousand dollars, plus airfare and expenses. I’ll fly coach if it’ll make it more affordable for your firm. I don’t require a four-star hotel, either. But I won’t be hamstrung if I need to move around or have to pay cash for information. I’ll ballpark the fee at nine thousand. Total.”

She scanned the room as if mulling the amount. She already sensed I was living out of the office and, worse, had no other work pending. She’d been here nearly twenty minutes and my phone still hadn’t rung.

“I can get Insight Security to do this one for six thousand,” she countered. “They’re our usual firm for Asian cases. Based in Bangkok, too.”

“I can go eight.”

“Seven thousand. Consider this case an investment in your future.”

“Seventy- fi ve hundred. I’ve heard the future won’t be cheap.”

“I do feel bad about your eye. Agreed.”

After expenses, the fee would cover my monthly nut for at least three months and let me make a dent in the Visa bill. The interest payments alone on the plastic debt were killing me. We stood to shake hands and I gave her my standard advisory, the same one I had recited Sunday night before agreeing to tail her husband: I never guaranteed results. I only guaranteed effort.

“I’m counting on both. You don’t seem the type of man who disappoints people.”

She smiled and patted my bruised face.

“Get to work, and finish strong, Sebastian. Unlike that rabbit.”

And then she was gone, although her Chanel perfume lingered in the room, a piece of pressing, unfinished business. The lilt of bossa nova from the ground- floor Brazilian mercado finally broke the silence. I sat down at my desk, took a deep breath, and opened the scented file filled with alien scribbling that was about to send me to another world.

Copyright © 2013 by Christopher R. Cox

Christopher R. Cox has made more than thirty trips to Thailand and always managed to avoid trouble with the police. His upcoming mystery-thriller, A Good Death (Minotaur) features corruption aplenty in Bangkok’s Thonglor district.

I am looking forward to reading this. A friend spent Vietnam stationed in Bangkok.

sound quite interesting

If you want to enter for a chance to win a copy, be sure to go to [b][url=http://www.criminalelement.com/blogs/2013/02/where-in-the-world-thailand-makes-for-perfect-crime-film-backdrop-christopher-r-cox-thriller-detective-ian-fleming-james-bond-c-i-a]Christopher Cox’s post on crime films in Thailand[/url][/b] and leave a registered comment!

i like down on their luck PIs. they do seem to be a stock character, but where would all of the readers be if we did away with stock characters. it is always interesting to see what an author does with them. This book sounds interesting.

i like down on their luck PIs. they do seem to be a stock character, but where would all of the readers be if we did away with stock characters. it is always interesting to see what an author does with them. This book sounds interesting.