In December 2002, two burglars broke into the Vincent van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. They didn’t use helicopters or lasers or any of the stuff art thieves use in the movies; they climbed a fifteen-foot ladder to the roof and got into the second floor (European first floor), where the main display halls are. They tripped alarms, but the police didn’t respond. When they busted a window and slid down a rope to get to the ground, they had souvenirs: two van Gogh oils.

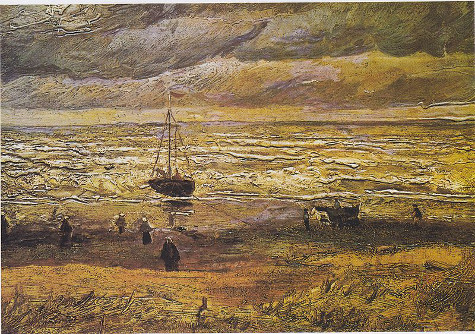

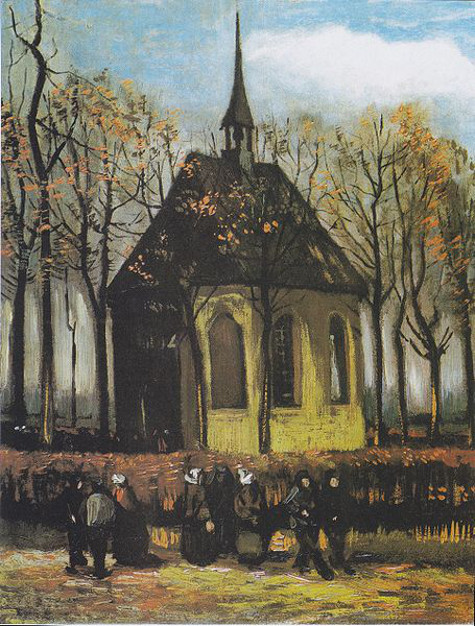

Both came from early in van Gogh’s artistic career. He created View of the Sea at Scheveningen, his only surviving seascape, in 1882 after only a year of practice at painting. Two years later, he gave Congregation Leaving the Reformed Church in Nuene (where his father was pastor) to his mother to amuse her after she’d broken her leg. Because they were such early works and showed van Gogh’s development as an artist, they were considered especially valuable … but apparently not valuable enough to insure. Eventually, the figure $100 million got attached to them, but it’s anyone’s guess.

This wasn’t the first time someone knocked over the Van Gogh Museum. On April 14, 1991, armed thieves surprised the guards when they came on duty and forced them to turn off the alarms. The thieves then spent 45 minutes picking twenty canvases they wanted to take home, including one of van Gogh’s famous Sunflowers still lifes. They got to keep the paintings for a whole 35 minutes before the police rounded them up and sent them to artless jail cells for six to seven years each.

In 2002, though, the police weren’t so fast. The thieves left a lot of evidence behind—the ladder and rope, a hat, some cloth, and a load of DNA—but the police didn’t catch them until December 2003. Octave Durham (a professional art thief known as “The Monkey”) and Henk Bieslijn were hardly Thomas Crown, as you might’ve guessed from their leaving so much evidence behind. The Monkey and Bieslijn went upriver for four and a half years each.

One problem: the two van Goghs were still missing.

They weren’t the only ones. ArtNet News estimates that 85 van Goghs are still missing after having been stolen. Another thirteen have been swiped—two of them twice—and recovered. Van Gogh was extremely productive (850+ oils in less than ten years, plus another 1300+ prints), his paintings are everywhere (including places with skimpy security or staff with flexible work ethics), and they sell for a mint; it’s pretty inevitable that they’ll be artnapped from time to time.

The museum did what museums often do: it posted a reward of €100,000 for the two paintings’ return while not holding out much hope they’d turn up. Stolen artworks that aren’t found in the hands of the thieves who took them have a nasty habit of disappearing for a long time. Sometimes they get sold into the black market (usually for 7-10% of their open-market value); sometimes they’re hidden; and sometimes they’re destroyed, as in the case of Marielle Schwengel, who in 2001 disposed of perhaps sixty 16th and 17th-century paintings that her son Stéphane Breitwieser stole.

Nobody claimed the reward. The two van Goghs faded into the purgatory for missing artwork. Axel Rüger, the museum’s director, said, “After all those years, you no longer dare to count on a possible return.”

Fast-forward to 2016.

The Guardia di Finanza, one of Italy’s various paramilitary police organizations, was conducting an investigation into the Amato-Pagano clan of the Camorra, the Neapolitan mafia lately the subject of Gomorrah, Italy’s highest-rated TV series. The Guardia is the Ministry of Economy and Finance’s main law-enforcement arm. In addition to going after financial crimes, it’s become, in essence, Italy’s answer to the DEA.

See also: Crime Under the Volcano: Introducing Gomorrah

Anyway, in January 2016, the Guardia arrested several traffickers connected to the Amato-Paganos’ cocaine operation. As the Guardia started chasing down the traffickers’ assets, Mario Cerrone—one of the arrestees—tipped the cops that Raffaele Imperiale—one of his fellow arrestees—might have something interesting stashed in a safe house in Castellammare di Stabia, near Pompeii.

It was a good tip. In September 2016, the Guardia raided the farmhouse and found two paintings wrapped in cloth. They were the two missing van Goghs.

How did the paintings end up in the Camorra’s hands?

It’s still under investigation. The Camorra are up to their necks in money that needs laundering. Cerrone called the van Goghs “investments”; maybe the clan thought buying the paintings cheap and selling them dear into one of the various black holes for hot art (such as the Persian Gulf or China) was a smart play.

For now, the two van Goghs will be guests of the Italian government. They’re evidence, after all. Given how slowly the wheels of justice turn in Italy, they may be there for quite some time. At least we’ll know where they are.

Fan of art crime? Read Lance's review of The Scientist and the Forger!

Lance Charnes is an emergency manager and former Air Force intelligence officer. His upcoming art-crime novel The Collection (Available November 14, 2016) involves the search for a cache of stolen paintings that may be in the hands of the Calabrian mafia. His Facebook author page features spies, shipwrecks, art crime, and archaeology, among other things.