United Flight 629: America’s First Mass Murder in the Sky

By Philip Jett

March 21, 2019

It was 1955. McDonald’s franchised its hamburger joints, Disneyland opened its doors to a magical world, and Elvis Presley commenced gyrating to screaming crowds. Times were changing. And United Air Lines Flight 629 exploded in the air killing everyone onboard to become the first bombing of a domestic aircraft and the worst act of mass murder in U.S. history at that time.

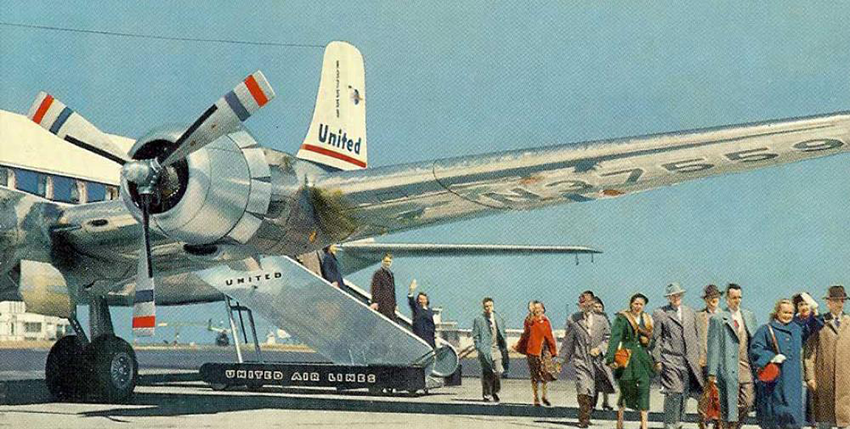

Air travel in 1955 was much different than today. Commercial flights were still somewhat novel for recreational travel. Most Americans had never flown. Airports were casual and welcoming. There were no TSA security checks or even metal detectors. No IDs were required. There’d been no Pam Am Flight 103, no 9/11, no frequent mass shootings. Travelers walked up to a counter, purchased a ticket, hugged relatives at the gate, and walked across a tarmac to board their plane while waving goodbye. It was a simple and innocent time—that was about to change.

On November 1, 1955, thirty-nine passengers and five crew members waited to board Flight 629 at Stapleton Airfield in Denver, Colorado, heading for Seattle. Those who waited chatted with family while others read books or newspapers or helped themselves to the flight insurance kiosks where they could purchase thousands of dollars of life insurance for only a few quarters. Sales were brisk since most Americans felt wary of flying, preferring the perceived safety of trains and buses.

When the time came for the passengers to board, they kissed and hugged their loved ones before stepping through a door to the outside’s freezing cold. They held their hats and gripped their coat collars as they strode across the windy tarmac to the ramp stairs. The four-engine Douglas DC-6B that United Air Lines had christened “Mainliner Denver” was a propeller-driven plane that could hold sixty or so passengers (about average at that time) and could cruise at 300 mph to 20,000 feet. Those stepping into the plane included twenty-six men, seventeen women, and one little boy, whose ages ranged from eighty-one years to fourteen months. The crew included two pilots, a flight engineer, and two flight attendants. As everyone nestled into their seats and buckled their seatbelts, all expected to be landing safely at their destination in about four hours.

Flight 629 took off at 6:52 p.m., twenty-two minutes behind schedule. At 7:03 p.m., only eleven minutes following takeoff, several residents of Longmont, Colorado, heard two explosions and witnessed blistering flashes of light against low-lying clouds. When nearby residents and authorities reached the balls of fire erupting from craters in a soggy beet field, they witnessed twisted and torn metal and bodies strewn across six square miles. The passengers’ bodies were quickly recovered and transported that evening to a makeshift morgue at a National Guard armory in nearby Greeley, fifty miles north of Denver.

Flight 629 took off at 6:52 p.m., twenty-two minutes behind schedule. At 7:03 p.m., only eleven minutes following takeoff, several residents of Longmont, Colorado, heard two explosions and witnessed blistering flashes of light against low-lying clouds. When nearby residents and authorities reached the balls of fire erupting from craters in a soggy beet field, they witnessed twisted and torn metal and bodies strewn across six square miles. The passengers’ bodies were quickly recovered and transported that evening to a makeshift morgue at a National Guard armory in nearby Greeley, fifty miles north of Denver.

Investigators from the Civil Aeronautics Board soon arrived. It was determined that the plane had exploded at an altitude of 10,800 feet while still climbing. Had there been a mechanical failure? Had the airplane’s fuel exploded? Or, had there been sabotage? It didn’t take long for the seasoned investigators to detect an odor like firecrackers. They also spotted gray and black soot on fragments of the plane’s skin and some of the luggage. The FBI was called in immediately and samples were sent to the FBI Laboratory in Washington, D.C. Agents determined that the plane had been sabotaged with dynamite, which appeared to have originated from rear cargo pit number four. One of the ripped and scorched suitcases in that luggage hold was traced to Daisie King.

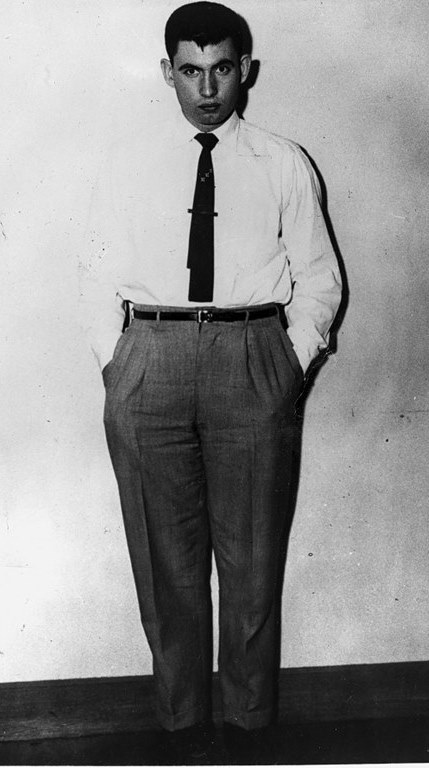

Daisy “Daisie” Walker King was a fifty-three-year-old Denverite who’d been divorced once and widowed twice. She had struggled financially during the Depression and had given up her young daughter and son to relatives and orphanages.  When she married her third husband, she was at last financially able to care for her children, but chose not to reclaim them. After her third husband’s death, when she was worth more than $100,000 (around $1 million today), she finally reunited with her adult children and tried to make amends. It didn’t work. Her son, John “Jack” Graham, hated her for abandoning him and that hatred had only festered since she’d rejoined him.

When she married her third husband, she was at last financially able to care for her children, but chose not to reclaim them. After her third husband’s death, when she was worth more than $100,000 (around $1 million today), she finally reunited with her adult children and tried to make amends. It didn’t work. Her son, John “Jack” Graham, hated her for abandoning him and that hatred had only festered since she’d rejoined him.

The FBI investigated all the passengers on board Flight 629 and their relatives, business associates, and enemies. Agents soon discovered that Daisie’s son had a minor police record and had filed two suspicious insurance claims previously. The FBI learned from Daisie’s daughter-in-law that Jack had secretly placed a “surprise Christmas gift” in Daisie’s suitcase, presumably a craft tool kit. It would later be determined that it was instead a bundle of twenty-five sticks of dynamite, two blasting caps, a timer, and a 6-volt battery that had been set to detonate in ninety minutes—what every mother wants for Christmas. A search of the home also uncovered an insurance policy on Daisie’s life purchased from the airport kiosk for $37,500 ($350,000 today) of which Jack was the beneficiary. FBI agents also discovered electrical wire identical to the type used to fashion the homemade bomb. A local hardware store operator identified Jack as a recent purchaser of dynamite. Presented with the damning evidence during an FBI interview, Jack confessed. He was only twenty-three years old.

Because a state murder case could produce the toughest penalty, Colorado filed charges against Jack for the intentional and premeditated murder of his mother. He quickly recanted his confession and pleaded not guilty. On May 5, 1956, after seventy-two minutes of deliberation, a Colorado jury convicted Jack of first-degree murder. He was executed in the gas chamber at the Colorado State Penitentiary on January 11, 1957, only fourteen months after the explosion of Flight 629.

The bombing prompted President Eisenhower to sign a bill that made it a federal crime punishable by death or life imprisonment for a person to “place . . . any explosive or other destructive substance in” an aircraft or motor vehicle used in interstate commerce that causes death. Though the law changed, airport security changed very little. Considered too expensive, passenger IDs and the x-ray of luggage and detection of metal on passengers weren’t mandated until 1972 in response to rampant hijackings of commercial airliners.

As he stood at the airport gate waiting for more than an hour for his mother to board on that cold November 1, 1955 evening, Jack Graham had plenty of time to study the faces of the people whose lives were about to be blown apart in the sky because of his hatred and greed. “I realized that there were about fifty or sixty people carried on a DCB,” Jack told a court-appointed psychiatrist. “But the number of people to be killed made no difference to me; it could have been a thousand. When their time comes, there is nothing they can do about it.”

With the detonation of that single bomb in 1955, America’s innocence in the sky had ended.

Read an excerpt of Philip Jett’s true-crime novel The Death of an Heir!

Comments are closed.

Pretty! This has been an extremely wonderful article. Thank you for providing this information.