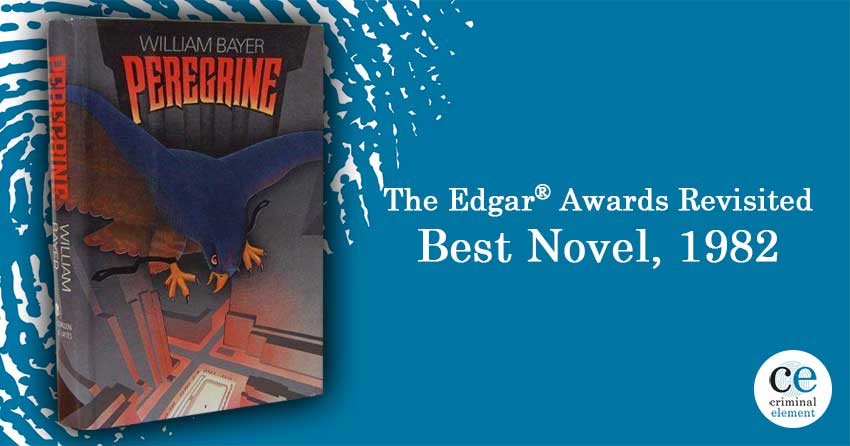

The Edgar Awards Revisited: Peregrine by William Bayer (Best Novel; 1982)

By Thomas Wickersham

July 19, 2019We've seen horrific hounds and savage sharks, but it was a fatal falcon that dominated 1982's Edgar winner for Best Novel.

A killer is on the loose. Soaring through the skies above Manhattan, one of nature’s most deadly predators, a peregrine falcon, eyes its potential prey on the sidewalks below. A flash of reflective light on the ground marks the target and signals the moment to strike. A beautiful ice skater is attacked from the sky at unfathomable speed, her throat ripped by the mighty falcon’s talons. So begins Peregrine’s rule of terror over New York City.

Fictional detectives have long been tormented by disreputable pets. Going back to the turn of the last century, Sherlock Holmes was faced with slobbering hounds and slithering swamp adders and their nefarious masters. The following decades saw both beast and man descend into a greater depravity of violence on the page and screen. Animal horrors left destination beaches and entire towns in bloody shambles. Serial killers stalked trick-or-treaters and slaughtered nubile camp counselors. And in 1981 domesticated terror came from the sky in a most sinister depiction of murderous falconry: William Bayer’s novel Peregrine, winner of the 1982 Edgar Award for best novel of the year.

See More: Revisiting the Edgar Awards

Professionally frustrated TV newswoman Pamela Barrett happens to be walking by the Rockefeller Center ice rink when she witnesses the first falcon attack and has the wherewithal to chase down the Japanese tourists who were filming the rink and commandeer their film for her station’s nightly news. Suddenly a star reporter, Pam becomes the face of New York’s most sensational news story. However, what most assume to be a freak occurrence quickly takes a more sinister turn as the bird strikes again, and again. After falconry experts confirm that the attacks are the work of a trained hunting bird and its handler, street-hardened NYPD Detective Janek is assigned to the case.

Peregrine is an odd mix of the conventionally formulaic and the uniquely demented. The novel begins like an episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show written by Ed McBain, and it ends like an episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show written by Jim Thompson. Pam is a smart and intrepid reporter, undervalued by her gruff and casually racist old-timer boss (there’s even a sozzled meteorologist with an air of Ted Baxter about him). Detective Janek enters the newsroom to interview Pam for the first time and takes a hardboiled internal assessment of her, “[S]he was beautiful, a perfect American face and wondrous thick brown hair—educated, ambitious, sharp-tongued, attractive, one of those girls who could cook an omelet but couldn’t face the thought of washing clothes.” Detective Janek has one unusual personal hobby: repairing accordions. This tidbit means nothing to the rest of the book, but it is an early hint of its general strangeness. With Pam already investigating the killer bird with tenacity equal to Janek’s, these two intrepid truthseekers start down the long road to untold ornithological horrors.

It is an outlandish premise of bird as murder weapon, but the initial stages of police detective and investigative reporter inquiries are standard mystery novel fare, albeit with shades of Jaws, The Most Dangerous Game, and the modern serial killer novel pioneered by Shane Stevens’s 1979 thriller By Reason of Insanity (and later popularized by Thomas Harris, whose first Hannibal Lector novel Red Dragon was also released in 1981 one month after Peregrine). William Bayer is clearly capable of writing a competent, tight, conventional thriller. Thankfully Bayer is not content with convention, and he slowly allows madness to bleed through the page. Yet nothing in the first 100 pages of Peregrine hints at the looming grotesqueries of sex, violence, and taxidermy to come.

It takes a killer bird to catch a killer bird. Following the advice of a local falconry expert, Pam’s TV station pays to fly legendary falconer Yoshiro Nakamura and his hawk-eagle “Honorable Kumataka” over from Japan, and puts man and winged predator up at the Plaza. A challenge is issued over the airwaves: Honorable Kumataka will duel Peregrine over Central Park in an ariel cockfight. Despite Pam’s misgivings over the tastefulness of Nakamura saying that his hawk-eagle will eat Peregrine, Pam’s boss is delighted by this:

The incredible arrogance of that little Nip…To the victor go the spoils. If Honorable Kumataka kills falcon, she deserves to eat falcon. It’s a tough airspace out there, folks. Bird eat bird as I always say.

The duel is a thrilling set-piece. “There were dives and forays, reckless pursuits at enormous speeds, so fast [Pam] was left with only impressions: a wing, a tail, a sight of talons, a flashing head, a beak. They were like fighter planes, she thought, kamikaze planes.” Peregrine triumphs over the hawk-eagle and later that night Nakamura is found dead, having committed ritual suicide over the corpse of Honorable Kumataka, though the reader is told that this gesture is “meaningless” since Nakamura “was not of the samurai class.”

The madness doesn’t stop there.

New Yorkers are living in a state of terror. Death can strike from the sky at any moment. People only leave their homes at night believing that the falcon exclusively attacks in the daylight. Street peddlers sell Peregrine masks and defensive bags of pepper, canes, and umbrellas for warding off bird attacks. The theaters around 42nd St. show double features of The Birds and The Maltese Falcon. One man isn’t afraid to be outside: the murderous falconer has nothing to fear and certain needs to attend to. When earlier attacks are described from his perspective the language is near-sexual, “At last he felt free, free of his earthboundness, sharing the thrill of the flight, the ecstatic moment of the hit and now the kill. The kill!…[W]hen he saw the blood, he felt requited, as if a terrible knot had been untied and warm liquid could flow free at last…” The killer’s actual sex life is no less twisted. He visits a prostitute, tying leather jesses to her ankles, placing a human-sized leather falcon’s hood over her head, and dressing her in a rich feathered cape, “a costume he sometimes wore himself.” The act itself is consecrated in a flurry of flapping wings, “rasps and chirps,” with mid-coitus fantasies of bringing his “falcongirl” a slaughtered baby rabbit. This scene of anthropomorphic intercourse signals the climax of the book, a bizarre height of perversity that while played straight, leaves the reader not terrified, but giddy at its absurdity. From this point on, Bayer seems more assured, as if his terrible knot had been untied, and the book races to its breathless conclusion featuring a second human-sized falcon hood, a secret room of taxidermied winged mutants, and an aerie at the top of the Empire State building.

Madness is where Peregrine triumphs. While its foundation is intriguing and serviceably executed, as written by Bayer, dedicated detectives and diligent reporters simply cannot match the passion of a murderous falconer who fetishizes mating in mid-flight. Once unfettered by good taste, traditional plotting, or any semblance of sanity, Peregrine becomes its own unforgettable beast.

Fun Facts from the 1980 Edgar Awards:

- It was an exceptionally strong year for the Best Motion Picture category with Cutter’s Way (based on Newton Thornburg’s classic novel Cutter and Bone) beating out Prince of the City, The Eye of the Needle, and Body Heat.

- Robert W. Greene won Best Fact Crime for his book on the Abscam scandal, The Sting Man. The 2013 David O. Russel film American Hustle was based on the same true story, though Greene’s book was not credited as source material.

- Stuart Woods won Best First Novel for his debut, Chiefs.

- A Talent for Murder by Jerome Chodorov and Normon Panama won one of the Edgars more sporadic awards, Best Play. The award was not given again until 1986.

- The other Best Novel nominees were Bogmail by Patrick McGinley, Death in a Cold Climate by Robert Barnard, Dupe by Liza Cody, The Amateur by Robert Littell, and The Other Side of Silence by Ted Allbeury.

Comments are closed.

Seems a shame to reward such a wacko entry when “The Amateur” was a clearly superior entry.