The Wicked Boy: The Mystery of a Victorian Child Murderer by Kate Summerscale is a deeply researched and atmospheric murder mystery of late Victorian-era London.

The Wicked Boy: The Mystery of a Victorian Child Murderer by Kate Summerscale is a deeply researched and atmospheric murder mystery of late Victorian-era London.

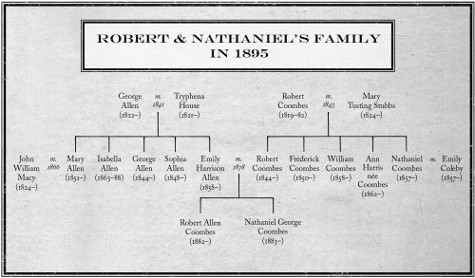

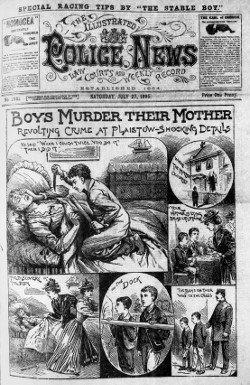

In the summer of 1895, Robert Coombes (age 13) and his brother Nattie (age 12) were seen spending lavishly around the docklands of East London — for ten days in July, they ate out at coffee houses and took trips to the seaside and the theater. The boys told neighbors they had been left home alone while their mother visited family in Liverpool, but their aunt was suspicious. When she eventually forced the brothers to open the house to her, she found the badly decomposed body of their mother in a bedroom upstairs. Robert and Nattie were arrested for matricide and sent for trial at the Old Bailey.

Robert confessed to having stabbed his mother, but his lawyers argued that he was insane. Nattie struck a plea and gave evidence against his brother. The court heard testimony about Robert's severe headaches, his fascination with violent criminals and his passion for 'penny dreadfuls', the pulp fiction of the day. He seemed to feel no remorse for what he had done, and neither the prosecution nor the defense could find a motive for the murder. The judge sentenced the thirteen-year-old to detention in Broadmoor, the most infamous criminal lunatic asylum in the land. Yet Broadmoor turned out to be the beginning of a new life for Robert—one that would have profoundly shocked anyone who thought they understood the Wicked Boy.

At a time of great tumult and uncertainty, Robert Coombes's case crystallized contemporary anxieties about the education of the working classes, the dangers of pulp fiction, and evolving theories of criminality, childhood, and insanity. With riveting detail and rich atmosphere, Kate Summerscale recreates this terrible crime and its aftermath, uncovering an extraordinary story of man's capacity to overcome the past.

EXCERPT

During the hot, dry summer of 1895, Robert and Nattie Coombes, aged 13 and 12, were living in their home in East London with a friend, a 45-year-old dockhand named John Fox. The boys’ father was at sea, the brothers told the neighbours, and their mother was visiting family in Liverpool.

As the milkman left his delivery on the doorstep of 35 Cave Road early in the morning of Wednesday 17 July 1895, he noticed a horrid smell emanating from the building. He informed the neighbours, who sent word to the boys’ aunt.

Aunt Emily turned up at 35 Cave Road at 9 a.m. No one answered when she knocked, so she collected her friend Mary Jane Burrage from her home, and at 10 a.m. they once more tried Emily Coombes’s front door. Since there was still no reply, the two women decided to call on Robert and Nattie’s grandmother in Bow, to see if she knew what was going on.

The 74-year-old Mary Coombes lived on the edge of Bow Cemetery in a two-up, two-down terraced house. Aunt Emily asked her if she knew the whereabouts of her other daughter-in-law Emily, whom they had ‘lost’. The older Mrs Coombes said that she had no idea where she was. Emily assured her that they would find the missing woman that day.

Mary Jane Burrage sent a telegram to the older sister of Robert and Nattie’s mother, and that same morning received in reply a telegram from Liverpool stating that Emily was not there. Robert and Nattie’s uncle Nathaniel tried the Cave Road house himself, then went to look for the boys in the recreation ground. He could not find them.

At 1.20 p.m., Aunt Emily and Mary Jane Burrage banged again at the door of 35 Cave Road. At first there was no reply, but at their second knock Robert opened the door. Emily pushed past him, followed by Mrs Burrage, and marched through to the back of the house. Robert, Nattie and John Fox had been playing cards – Nattie scrambled them up when he saw his aunt. He rose to his feet but Fox stayed in his chair, smoking a pipe. A strong smell of tobacco permeated the room.

Emily asked Robert where his Ma was.

‘She is with Mrs Cooper,’ Robert said. ‘I will take you to see her.’

‘No,’ said Emily. ‘Your Ma is in this house, and I won’t go away until a policeman comes.’

‘All right,’ said Robert.

On hearing his aunt’s warning, Nattie climbed out of the back parlour window and ran for the market gardens beyond the yard.

Emily asked Robert whether she could go into his mother’s room.

‘No,’ he said. ‘It is locked.’

She asked him where the key was, and he replied that he did not know.

‘All right,’ she said. ‘I will burst open the door.’

Mrs Burrage said to Robert: ‘Your mother is lying dead in that room upstairs.’

‘No, she isn’t, Mrs Burrage,’ said Robert. ‘She’s in Liverpool.’

‘I don’t believe it,’ said Mrs Burrage.

She and Aunt Emily went upstairs, but when they tried to force the door found that it would not give. They sent someone to fetch a spare key from the landlady. The key was brought, and Aunt Emily opened the door to the bedroom. There she saw the form of a woman, lying on the bed, the face covered by a sheet and a pillow. Overcome by the smell of rotting flesh, she drew back and sent Mary Jane Burrage and her son to find a policeman.

Now that the bedroom door was open, the stench spread swiftly through the house. At 1.30 p.m. Harriet Hayward, of 39 Cave Road, approached the front door and bent to peer through the frosted glass panels to see if she could spy the boys in the passage. She was startled by the smell issuing from the letter box. The day was becoming intensely hot. A black cloud of blowflies hovered at the upstairs windows. Mrs Hayward hurried away to fetch Mrs Robertson from number 37. ‘Come and have a smell,’ she urged her.

***

Mrs Burrage found Constable Robert Twort in Greengate Street, a block away from Cave Road. Twort went straight to the house, where Aunt Emily showed him upstairs.

In the front bedroom, PC Twort turned down the sheet and lifted the pillow to reveal a woman’s body, severely decomposed and swarming with maggots. He saw a knife on the bed and a truncheon on the floor. He sent word to the police station, asking for an inspector and the divisional surgeon to come to the house at once.

In the front bedroom, PC Twort turned down the sheet and lifted the pillow to reveal a woman’s body, severely decomposed and swarming with maggots. He saw a knife on the bed and a truncheon on the floor. He sent word to the police station, asking for an inspector and the divisional surgeon to come to the house at once.

Aunt Emily approached the bed and looked at her sister-in-law’s body, but the face was so disfigured that she could not recognise her. She returned to the back parlour, where Robert was standing by the window. Fox was sitting on a chair between the door and the dresser.

‘You are a bad, wicked boy,’ she told Robert. ‘You knew your Ma was dead in the room and you ought to have told me.’

‘Auntie,’ he replied. ‘Come to me and I will tell you the truth and tell you all about it.’

His aunt went towards him.

‘Ma gave Nattie a hiding on Saturday for stealing some food,’ said Robert, ‘and she said, “I will give you one too.” Nattie said: “I will stab her. No, I can’t do it, Bob, but will you do it? When I cough twice, you do it.” I did do it.’

Emily asked him if his mother was awake at the time.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘She was lying with a hand over her face.’

‘Did your Ma cry?’

‘She did not cry nor speak. I covered her up and afterwards went away to Lord’s cricket ground.’

Emily asked at what time he had killed his mother.

‘About a quarter to four on the Monday morning,’ said Robert, ‘a week ago. I slept with Ma that night and I kicked about a great deal, and she punched me. Nattie was in his room. I did it by myself.’

She asked how he had killed her.

‘I got out of bed and I stabbed her,’ said Robert. ‘Nattie was in the back room, and coughed twice, and that was when I done it, when Nattie coughed. I did it with a knife, and it is on the bed.’

From The Wicked Boy: The Mystery of a Victorian Child Murderer by Kate Summerscale. Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © Kate Summerscale, 2016.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Kate Summerscale, formerly the literary editor of the Daily Telegraph, is the author of The Queen of Whale Cay, which won a Somerset Maugham Award and was short-listed for the Whitbread Biography Prize. The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher was a #1 bestseller in the UK, has been translated into more than a dozen languages, was short-listed for the CWA Gold Dagger for Non-Fiction and the Edgar Award for Best Fact Crime, and won the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction and the British Book Awards Book of the Year. Summerscale lives in London.