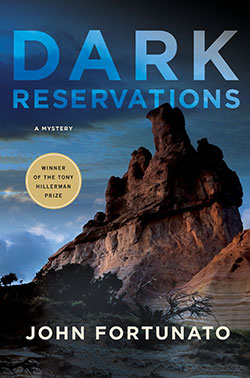

Bureau of Indian Affairs special agent Joe Evers still mourns the death of his wife and, after a bungled investigation, faces a forced early retirement. What he needs is a new career, not another case. But when Congressman Arlen Edgerton's bullet-riddled Lincoln turns up on the Navajo reservation—twenty years after he disappeared during a corruption probe—Joe must resurrect his failing career to solve the mysterious cold case.

Joe partners with Navajo tribal officer Randall Bluehorse, his investigation antagonizes potential suspects, including a wealthy art collector, a former president of the Navajo Nation, a powerful U.S. senator, and Edgerton's widow, who is now the front-runner in the New Mexico governor's race. An unexpected romance further complicates both the investigation and Joe's troubled relationship with his daughter, forcing him to confront his emotional demons while on the trail of a ruthless killer.

Joe uncovers a murderous conspiracy that leads him from ancient Anasazi burial grounds on the Navajo Nation to backroom deals in Washington, D.C. Along the way, he delves into the dangerous world of black market trade in Native American artifacts. Can he unravel the mystery and bring the true criminal to justice, or will he become another silenced victim?

One

September 23

Thursday, 6:35 A.M.

Sky City Casino, Pueblo of Acoma, New Mexico

When Joe Evers arrived, his squad was already donning their vests and checking their weapons. He was late and had missed the briefing.

“You’re with us,” Stretch said. “Sadi and I have the rear. You have outbuildings and vehicles.” He handed Joe a picture of the subject, Roy Manygoats.

Cordelli was the case agent and had designated the casino’s rear parking lot as the staging area. From here, they would go to Manygoats’s residence to make the arrest. If he wasn’t there, they would go mobile, trying to track him down as quickly as possible.

Standing beside his vehicle, Cordelli spotted Joe. He shook his head and said something to Dale, who glanced at Joe and laughed.

“Let’s hurry up,” Dale said. He wore his vest high over his rather generous gut, the large, yellow BIA letters sitting just below his chin.

“What are you doing here?” Joe asked.

Dale walked away, ignoring his question. He rarely went on operations, not since becoming squad supervisor six years earlier, which coincided with his outgrowing his tactical vest. Too much desk time, he’d said. Too many tacos, the squad had said.

Stretch charged his M4 carbine. “He thought you would be a no-show.” The assault rifle appeared petite in front of his six-foot-seven frame.

Perhaps it was guilt, but Joe thought his friend and former partner was going to add again. He put on his vest and started for the passenger door of Stretch’s unmarked Suburban.

“Don’t even think about it,” Sadi said, and reached past him for the handle. She jogged a thumb toward the backseat.

They traveled in convoy, three vehicles, into the heart of Acoma, which was located off I-40, west of Albuquerque. This was Indian Country. Reservation land. Rural, desolate, and hard.

Four dirt roads later, they arrived at a trailer a little more than a mile from an adobe village that sat atop a plateau and was known as Sky City. As they pulled up, a couple of scrawny rez dogs came from behind the building, both mutts, both starving. Stretch drove to the rear, stopping ten feet from the back door. They climbed out, guns drawn.

The other half of the team was at the front door, making entry.

A few hundred feet behind the trailer were the remnants of a corral, two abandoned vehicles, and an outhouse.

Cordelli’s voice came through the radio. “His mother’s saying he’s not here.”

Joe checked the vehicles. Empty. He made his way to the dilapidated corral and searched behind a pile of car tires. The land here was devoid of trees, only scrub grass and a few scraggly bushes, no place for a person to hide.

He moved on to the outhouse, a plywood special in need of paint. From twenty or so feet away, the air was already redolent with the smell of human waste. Tasking him with the outhouse was punishment. He was the senior agent, but he’d been put on the perimeter. He’d been put on shit duty.

A dog barked.

Sadi and Stretch were by the back door of the trailer, which was now open. Cordelli stood in the entryway. One of the mutts challenged them from the building’s corner.

A sound emanated from the outhouse, a soft creaking. Joe raised his Glock.

“Police! Come out!” he said, not sure if there was someone inside, but not wanting that person to hear his uncertainty.

The door burst open and a skinny kid in a blue T-shirt came running out, away from Joe, into the open field beyond.

Joe cursed and holstered his weapon, then took off after him. It wasn’t a kid, but a teenager. He called for the teen to stop.

The runner ignored him, heading toward an arroyo some two hundred yards beyond. The ground was rocky and dotted with flat cacti and mesquite brush, but the teen proved agile. Joe knew he was too old and too out of shape to chase this guy far. All he could do was try for an all-out sprint and get him quickly, or else let him go. He took longer strides and focused on his breathing. The gap between them closed. The teen turned.

It was Manygoats. All nineteen years of him. He had the look of a rabbit chased by a dog—an old dog.

Joe reached out and grabbed for his shirt. Fabric ripped. The effort threw Joe off balance and he stumbled forward, taking long, erratic bounds to stay upright. But he was going too fast. He fell to the ground, dragging the teen with him. They rolled. Joe lost hold of the shirt. They both came up on a knee. Manygoats’s eyes revealed the terror of a man facing a lifetime in prison.

“Don’t make it worse,” Joe said between breaths.

Manygoats tried to get to his feet.

Joe lunged and slammed him to the ground. They wrestled. Joe felt movement by his right hip, his holster. Manygoats had the Glock halfway out. Joe clamped his right elbow down over his weapon and the young hand, then raked it backward with all his strength, knocking the weapon away. He seized the teen’s arm and wrenched it behind his back. Manygoats shifted and tried for the gun with his free hand, but he didn’t have the reach, and before Joe could retrieve it, a boot came down on the grip.

Cordelli stood above him.

Joe cuffed Manygoats, then dusted himself off.

Stretch grinned as he handed the weapon back to Joe. “Maybe I should hold on to that for you, seeing how much trouble you’re having with it?”

The rest of the squad gathered around them.

Dale wanted to know what had happened. Joe told him, leaving out the part about losing his weapon.

“Good work,” Dale said.

“Tell him about your gun, cowboy,” Cordelli said. Half Italian and half Ute, Cordelli had the face and body of Michelangelo’s David, with a mouth that spat arrowheads. Joe carried a few scars.

Stretch came to stand next to Joe. “Why don’t you shut up, Cordelli.”

“What about it?” Dale asked.

“Nothing. The punk tried to grab for it when I put him on the ground. I had it under control.”

“You’re just lucky I came along.” Cordelli pointed a finger gun at Joe. “You might’ve been retiring in a box.”

Stretch pulled Joe toward his vehicle.

“Write it up, Joe,” Dale said. “Get it to Cordelli before the detention hearing.”

A report would be embarrassing, but Joe didn’t argue. He had only three months left. At least things couldn’t get any worse.

SEPTEMBER 23

THURSDAY, 11:42 A.M.

BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, OFFICE OF INVESTIGATIONS, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO

Joe and Stretch stood in the middle of the squad room, looking up at the television suspended from the ceiling. The news ticker scrolling across the bottom of the screen announced breaking news. Authorities had found Congressman Arlen Edgerton’s vehicle on the Navajo reservation.

What the ticker did not tell viewers was that the congressman, two of his staff, and the vehicle they’d been traveling in had gone missing more than twenty years earlier. But soon the news anchor, a young, attractive brunette who looked strikingly similar to every other brunette news anchor, reported the full story, punctuating the facts with provocative questions that rivaled the skills of the most accomplished true-crime writer: Did the corruption probe prove Edgerton was taking money? Why, after a two-year-long investigation, did the independent counsel find only one suspicious transaction involving Edgerton?

“They’ll be spinning it by noon,” Stretch said.

“Who?”

“His wife. Her campaign. She’s dirty, just like he was.”

Joe nodded, not really caring. He knew his friend, knew he enjoyed passing judgment, everything black and white, never a shade of gray, never a faded edge.

On the screen, superimposed over the background to the assembly-line brunette, was a picture of Congressman Edgerton and his secretary, Faye Hannaway, he in a conservative dark gray suit, she in a red look-at-me dress. The photo appeared to have been taken at a campaign party. A banner in the background read ARLEN EDGERTON FOR CHANGE. It seemed only the candidates got swapped out, never the slogans.

“Joe!” Dale called from the doorway to his office. “Get in here.”

When Joe entered, Dale waved him to a seat in front of his desk. He ripped a sheet of paper from his notepad and handed it to Joe.

“That’s the number for the officer who found Edgerton’s vehicle.”

Joe stared at the paper, confused. On it was written “Randall Bluehorse,” below that a phone number.

“What’s this for?”

“You’re catching it. The FBI’s letting us run with it. We handled the disappearance back in ’88.”

“And I’m handling it? Bullshit. I’m out of here in three months.”

“Clear it and you go out big.”

“Is this because of this morning?”

“No. It’s because you’re still my senior agent.”

Dale didn’t say best agent. He wouldn’t say that. Not anymore. Joe tossed the paper to Dale. It landed atop a red ’76 Datsun 510, part of Dale’s model-car collection, a replica of the car Paul Newman had driven to win several of his first professional races.

“Get Stretch. Or your wonder boy Cordelli.”

“You refusing the assignment?” Dale leaned back in his chair. “If so, I can put you out right now. You’re the one with a kid in college, not me.”

Joe lowered his gaze, not because he was hurt or beaten, but because he knew if he stared at that puffed-up face any longer, he might launch himself across the desk.

“You’re an asshole.” He snatched up the paper and stormed out.

He marched past Stretch to his own cubicle, where he flung down the officer’s number.

What the hell was Dale’s game? He’d already won, had already gotten the board to force through Joe’s retirement, had already ruined his life. In the end, they had agreed that if Joe didn’t fight the review board’s decision, he could use his remaining time to wrap up cases and find a job. Now it seemed that deal was off.

He opened his center desk drawer and grabbed for his bottle of aspirin, what he thought of as his morning-after pill. He fumbled with the lid, his fingers jittery. It had nothing to do with his need for a drink. He wanted to punch Dale in his smug, fat face, not fiddle with the childproof dot and arrow.

He threw the bottle at his computer. The lid popped. White tablets sprayed over the papers and folders and a crumpled burrito wrapper on his desk.

He picked up two pills. Chewed them. Their chalky texture coated his mouth, not quite overpowering the bitter taste Dale’s words had left.

“What’d he want?” Stretch asked.

“He wants me to work the Edgerton case.”

“The vehicle? It’s FBI. What’s he want you to do with it?”

Joe picked up the paper with Bluehorse’s phone number.

“I guess he wants me to find Edgerton.”

SEPTEMBER 23

THURSDAY, 10:42 P.M.

OTHMANN ESTATE, SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO

Arthur Othmann unfolded the clear plastic painter’s tarp and spread it over the bone white carpet in his study. He stepped back to appraise his handiwork and then repositioned it so the sides were parallel to the display cabinets that ran the length of the room.

“Perfect,” he said to no one.

Muted voices carried from another part of the house.

He checked his watch, then smiled up at the oil portrait of his father, Alexander Othmann, founder of the once Great Pacific Mining Company, now both defunct. “They’re right on time, Pops.”

The portrait’s massive gold-leaf wood frame, ornately carved, clashed with the Native American artifacts displayed in the cabinets along the walls. Its shimmering trim and grotesque size gave it an otherworldly quality, a doorway to the spirit world, what the Navajo might call Xajiinai. According to their creation story, the Navajo emerged through Xajiinai, a hole in the La Plata Mountains of southwestern Colorado that allowed them to ascend from the underworld. Othmann knew all about Navajo history. It was, after all, their past that fed his passion for the arts. His father had never shared that passion. In fact, he hated that his only son, the last male carrier of the Othmann bloodline, was interested in the arts and was “a little light in his goddamn pants!” Toward the end of his life, his father would growl those words through wrinkled brown lips wrapped around a Padrón cigar, which looked like a shovel handle sticking out of the old man’s face. The son didn’t care about understanding his father, only outliving him. Not hard, considering the old bastard had been in his seventies when Arthur finished college. And during those seven years after his return from Stanford, where he’d studied art history, they had lived together in the house, with only a maid and a nurse (his mother had died his first year away—not a great loss), and it was during those seven years that the son had often fantasized about that shovel handle.

Once, after acquiring a rather spectacular ninth-century Anasazi watering bowl, he had shared his thoughts of the portrait with his bodyguard, David “Books” Drud, over a glass of celebratory scotch. “I like to think it’s a portal to the afterlife, and my father visits from time to time to see how I’m spending his money. And I get to kill the old bastard all over again.” Books gave a respectful chuckle and sipped the five-thousand-dollar-a-bottle whisky. But Othmann had not been joking.

The voices were in the hallway now.

He strode over to the stone mantel behind his desk. Atop it sat a wood carving of a rug-weaving loom. The tiny weaver’s seat had been hollowed out and a miniature camera installed. In a darkened room ten feet below the study, a twenty-five-terabyte digital recorder captured every moment on Othmann’s estate. He never skimped on security.

The door opened.

A middle-aged Navajo man stumbled in. Strands of long, black hair stuck to his face. His dirty clothes and the black patch over his left eye gave him the appearance of a down-on-his-luck desert pirate. At one time, this had been Othmann’s prized silversmith, whose work had been shown at the Smithsonian and sold in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré district in Paris. But when the Navajo silversmith had lost his eye in a drunken brawl four years earlier, he also lost his talent. Now he was just Eddie Begay, the snitch.

Books stepped behind Eddie, his imposing figure clogging the doorway. He shoved the skinny man forward. Eddie’s feet failed to keep up, and he fell to his knees onto the plastic tarp.

Eddie had grown comfortable groveling these past few years; alcohol seemed to lubricate his humility. Kneeling on the floor, he actually looked somewhat at ease.

“You doing some remodeling, Mr. O?” Eddie said.

Books moved to stand behind their guest.

“I thought we were friends, Eddie,” Othmann said, his voice soft, with just a touch of hurt.

“We are. You’re my bil naa’aash.”

“Cousin-brother. I like that. Yes, I suppose we are brothers of a sort. Brothers in art.”

Eddie must have put up a fight because Books’s right trouser leg was muddied and torn. Othmann was curious.

“His dog didn’t like it when I put Eddie in the car,” Books said, his voice slow, tired, as though his words had traveled a long way before passing his lips.

“He killed my dog, Mr. O. He slammed her head in the car door.”

“It was practically dead anyway,” Books said. “Nothing but skin and bones. You people don’t take care of your dogs.”

“Fuck you, man.”

Books was fast. Othmann almost missed it. He heard a slap, and then Eddie’s head snapped forward.

“Eddie,” Othmann said. “Look at me, Eddie. A little birdie told me you got caught diddling a kid.”

“I never done nothing like that. I got a woman. I don’t touch kids. If anyone told you that, they’re just trying to mess up our business arrangement.”

“That’s exactly what I wanted to talk to you about, our business arrangement.”

Eddie squinted. “I thought you were happy with the carving.”

“Oh, I’m very happy with it. And I have it on good authority it’s authentic.”

The carving was a chunk of stone with a thousand-year-old petroglyph of a spiral-beaked bird that Eddie had chiseled from a cliff at Chaco Canyon. It now sat below them as part of Othmann’s very private and very illegal collection in an environmentally controlled vault. And in that same vault was the recorder that was, at that very moment, capturing Eddie Begay’s every word.

Othmann continued. “Why don’t you tell us what the police are accusing you of, Eddie?”

“This is bullshit. I’m not telling you any—”

Books drove a knee to the back of his head. Eddie did a face plant on the tarp. He didn’t move.

They waited.

“I hope you didn’t kill him.”

Books shrugged.

Eddie let out a sound somewhere between a whimper and a groan and struggled back to his knees. His eye patch had shifted, granting Othmann an unwanted view of a black sunken hole. Was that what Xajiinai was? Black and bottomless? Not like his father’s portrait at all. Maybe Eddie was the portal to communicate with the dead, to communicate with good ol’ Pops.

“What did they say you did?” Othmann asked.

Eddie took several deep breaths. His good eye seemed unable to focus. “They said … they said I touched my sister’s boy. But I didn’t.”

Othmann walked around to the front of his desk, careful not to block the camera’s view. “And what did you tell the FBI about me?”

“How did you know it was the FBI?”

“Eddie, it’s time to be honest. I need to know I can trust you. Now, what did you tell them about me?”

“Nothing. Why would I talk about you? They were asking about my nephew.”

“Did you tell them about the carving?”

“No.” Eddie’s voice was high.

“What do you think, David? Did he talk?”

“He talked. A man that can’t take care of his dog isn’t loyal to anyone.”

“Are you loyal, Eddie?”

“Yes—”

Another knee to the back of his head.

They waited.

Books wrinkled his nose. “I think he shit himself.”

A minute passed.

Eddie regained consciousness. He groaned. Blood dripped from his nose onto the plastic.

“Oh man.” Eddie pulled at the seat of his pants.

“Stay on the tarp,” Othmann said.

The broken man sat back on his knees, swaying. A silver and turquoise squash-blossom necklace, which Eddie usually wore beneath his shirt, now hung exposed on his chest. It had been handed down through his family, originally belonging to his great-grandfather, who had been the chief of his clan before the Long Walk. Its craftsmanship was some of the best work Othmann had ever seen. But no matter how tough things had gotten for Eddie, he had never parted with his great-grandfather’s legacy.

“Eddie, Eddie. Why are you doing this to yourself? It’s a simple question. I already know the answer, but I want to hear you say it.”

“Okay … but don’t let him knee me anymore. I’m seeing double.”

“David, don’t knee him anymore.”

“Okay, boss.”

Eddie stared as Books unbuckled his belt. Books pulled it from his waistband and grasped both ends in his right hand, letting the loop dangle by his side.

Eddie whimpered.

“What did you tell the FBI about me?”

Eddie licked his lips, smearing the trickle of blood from his nose, spreading it wide, giving himself a clown’s red mouth.

“You’re right. I’m sorry. I got scared. Real scared. I was never in trouble like that before.”

“What did you tell them?”

“That I used to make jewelry for you, and when I couldn’t do that anymore, I started getting you things.”

“What things?”

“I told them about the prayer sticks … and the artifacts.”

“Did you tell them about the Chaco carving?”

Eddie hung his head.

“And they want you to talk to the grand jury, right?”

“I’ll disappear. I have a cousin in California. I can hide out there. Really. I won’t talk to them again. I promise.”

“I know you won’t.”

Books dropped the belt loop over Eddie’s head.

The silversmith clawed at the thin strip of leather.

Othmann stared into the dying man’s empty eye socket.

Later that night, in the environmentally controlled vault below, while replaying the hidden-camera footage, feeling the effects of Cuervo Black and a line of Christmas powder, Othmann would think about this moment and tell himself he saw his father staring out of that depthless black hole, the tip of his cigar glowing with the brilliance of hellfire, and his wrinkled lips mouthing the words You’re a little light in your goddamn pants!

SEPTEMBER 24

FRIDAY, 9:38 A.M.

BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, OFFICE OF INVESTIGATIONS, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO

Supervisory Special Agent in Charge Dale Warren thumbed through a copy of that month’s issue of Model Cars Magazine, pausing on an article about applying alclad chrome to bumpers and grilles. His cell phone rang. He recognized the number and answered.

“It’s assigned,” he said. “I gave it to one of my … older agents.” Dale disconnected the call without waiting for a response.

Then he picked up the 1952 Moebius Hudson Hornet convertible parked at the edge of his desk and eyed its bumpers. The metallic paint was dull and pitted from a poor application he’d attempted the previous summer. He laid the car back down and returned to the article.

SEPTEMBER 24

FRIDAY, 10:31 A.M.

JONES RANCH ROAD, CHI CHIL TAH (NAVAJO NATION), NEW MEXICO

Joe pulled his Tahoe behind the marked Navajo Police vehicle and stepped out. They were parked on the side of Jones Ranch Road in Chi Chil Tah, a small Navajo community twenty miles southwest of Gallup, consisting of a school, a small housing development, some scattered trailers and ranch homes, and a chapter house, the Navajo equivalent of a town hall. The blacktop had ended about four miles back, and now he stood on hard-packed clay surrounded by piñon trees.

The officer, who had been leaning against his ride’s front fender, approached. He wore the tan uniform of the Navajo Police Department, and wore it well, crisp and clean. A rookie.

“Agent Evers?”

“Call me Joe.” He flashed his credentials, then slipped them back into his sport coat. He didn’t ask the officer’s name. His name tag read R. BLUEHORSE.

A big grin spread across the officer’s face. He reached out and pumped Joe’s extended hand with all the enthusiasm of a teenager being given the keys to the car for the first time. “Glad to meet you. I’m pretty new to the force. My first week out on my own and I caught this case. Lucky, I guess.”

Lucky? A cold case? Lots of work and little chance to clear it. The kid had no idea.

Joe pulled his hand to safety. “Sorry, I’m a little late.” Mornings had become more and more difficult for him over the past year.

Bluehorse looked at Joe’s shoes. “Did I tell you it was in the woods?”

The cuffs of Joe’s wrinkled khakis sat atop a pair of tasseled loafers. No doubt boots would have been a better choice. “They’re old.” They weren’t.

The officer seemed to be waiting for something.

“You want to show me what you found?”

“Isn’t there anyone else coming? You know, to process it.”

“I need to check it out first.”

Officer Bluehorse looked down the road one last time, as though willing there to be more attention to his find. Then he walked to the north side of the road and set off through the woods. Joe followed.

This was the high desert, six thousand feet above sea level, just enough rainfall to support life. The trees were spread far apart, with a sprinkling of sage, rabbitbrush, and brown grass between them. The scent of sage was strong, almost overpowering. Joe studied the distance between trees. He guessed a car could zigzag a path through these woods if the driver didn’t care about beating the vehicle to hell.

“I plan on putting an application in with BIA or FBI when I finish my bachelor’s,” Bluehorse said.

“Go with the FBI. They offer dental.”

“Really?”

Joe smiled, something he’d not done in some time.

“Which would you recommend?”

“Either,” Joe said. “FBI if you don’t care where they send you. BIA if you want to work reservations the rest of your life.” And don’t mind being screwed over once in a while by your supervisor.

“I think I want to work reservations.”

Enjoy the screwing.

“So how did you find the vehicle?”

“We were searching for a missing hunter, and I just came across it.”

They arrived at a shallow arroyo. Joe slid down and could feel loose soil spill into his shoes. When they climbed out on the other side, he was breathing hard. It had to be the elevation and not the four or more beers a night—usually more—he told himself.

“Hold on.” Joe leaned against a tree and took off his shoes, one at a time, shaking them out as he filled his lungs. “What made you run the vehicle?”

“The bullet holes.”

“Bullet holes? Why didn’t you tell me about them when I called?”

Bluehorse shifted his weight to his other foot. “The car’s been here a long time. They could be from hunters having target practice. I didn’t want to sound the alarm. And you didn’t ask any questions.”

“I shouldn’t have to ask.”

The officer lowered his gaze. “Yes, sir. Sorry.”

Joe hadn’t meant to come off so harsh. “The news didn’t mention bullet holes.”

“I haven’t turned in my report yet. I wanted to keep that and the location quiet until you arrived.”

“That’s great, but how did the story even get out?”

“This is Navajo land,” Bluehorse said. “There are no secrets. I guess someone in the department talked.”

Joe slipped his foot back into his second shoe. He patted the trunk of a tree. “Is this oak?” he asked, trying to stretch out the break a little longer.

Bluehorse perked up. He peered toward the tree’s canopy. “A real fine one, too.” He touched the bark with his hand. “There’s a lot of oak here, mostly down by the canyons. The name Chi Chil Tah means ‘where the oaks grow.’ My grandpa was Hopi, a kachina carver. Do you know what they are?”

Joe did. Small colorful carvings of Indian dancers representing various spirits.

Bluehorse continued in a soft, almost sad voice. “He used to take me out this way when I was a kid to gather wood. Most kachinas are made from cottonwood root. It’s soft and easy to carve. But my grandpa made a special oak kachina for men with what he called ‘the wandering spirit.’ Oak is heavy, he’d say; it plants the man firmly with his family. He also made it for people who suffered great losses because oak was strong and could bear great burdens.”

“He sounds like a wise man.”

“He was. He died a few years back.”

Joe’s chest tightened. He felt for Bluehorse. For this young man’s loss. He thought of Christine, his own loss. Memories flashed through his head like a silent montage. Images of her. Images of them. He pushed them out of his head. Those memories were for the nights when he lay awake in bed, not having had quite enough alcohol to dull the pain, to bring on the blackness and the comfort of oblivion. On those nights, his memories would infiltrate his mind like termites, trying to destroy his will to go on without her. He stood in the woods now, struggling to catch his breath, but he couldn’t. He faced away and inhaled deeply. After a bit, he turned back. Bluehorse had his eyes closed and his left ear pressed against the tree.

“We’d sometimes wander these woods for hours till we found the right tree. He’d say he could hear the tree’s energy, its life. He’d take wood only from a healthy tree, never a sickly or dying one.” Bluehorse pushed himself off the trunk, turned, and started again through the woods.

Joe followed. He knew he had just witnessed something profound, something that should have given him a flash of insight into the human condition, or some glimpse of a universal truth. Instead, he just felt dull. His head hurt, memories of Christine still fighting to get back in. He trudged on, following the young officer, weaving between trees both living and dead.

They hiked the next ten minutes in silence, Bluehorse in front, maintaining an easy pace; Joe, some distance behind, breathing hard, trying to keep up. Finally they arrived, quietly, solemnly, forgoing any discussion that might herald the journey’s end.

Between two dead piñon trees, surrounded by sage and rabbitbrush, painted in shadows, out of place in this seemingly untouched wilderness, sat the remains of a bone white Lincoln Town Car.

Bluehorse had not downplayed its condition. There was little left. The doors were angled open, seats missing. The dash had been ripped apart, its wire innards dangling. Only brittle shards remained of the rear window. All the tires were gone, the axles resting on an assortment of logs and stones.

Joe made a slow circle around the remains. He detected the faintest scent of engine oil, surprising considering all the years the vehicle had rested there. Yet, at the same time, he knew the longevity of odor. He had been to many body recoveries over the years. And he knew how strong the smell of decay could be even after a decade under the earth, as if the dead refused to break their connection with the living.

The vehicle’s vinyl roof was shredded and its four headlights broken. Its front bumper lay lopsided, like a stroke patient’s smile. Three evenly spaced bullet holes cut across the windshield. Possibly some idiot’s idea of target practice, but it challenged the idea that Edgerton had simply skipped out with the money, which had always seemed a little too storybook for Joe.

He bent down by the rear bumper. On the left, faded, peeling, barely legible, was a sticker that read EDGERTON FOR CONGRESS. To the right of that was DUKAKIS FOR PRESIDENT IN ’88.

“Nice work.” Joe was being honest, but he wished the officer had waited three months to call it in. That way, Joe could have read about it at his new job. If he could find a new job.

“Thanks, sir.”

“Call me Joe.”

“So what’s all the fuss over Edgerton? I mean, I know he ran off with some money, but it’s not like he killed anyone.”

“At the time, it was pretty big. Right after the Iran-Contra scandal. People were upset about political corruption. I think Edgerton became everyone’s target. Also, it was sort of a mystery. What happened with all the money? Sort of like D. B. Cooper.”

“Who’s D. B. Cooper?”

Joe grinned. “When were you born?”

“1990.”

“Forget it.” Joe turned his attention back to the Lincoln. “Why don’t you give me your take on this?”

Officer Bluehorse straightened. “Yes, sir—I mean, Joe.” He walked to the engine compartment.

“The whole car’s been stripped, even the engine.”

Joe looked under the hood. In place of the motor was a pile of sticks and shredded bark. A pack rat’s nest.

“At first I thought the vehicle may have been put here after being stripped somewhere else. But I found an old trail right over there.” Bluehorse pointed north. “It’s overgrown now, but that must be how they got the engine out. Also, I found some of the engine parts under the car, so that told me they dismantled it here. Same with lug nuts and some dashboard pieces.

“I can’t be sure, but it looks like those three shots through the windshield were fired from a downward angle. My guess is the shooter was standing on the hood and fired down into the dash.”

Joe poked his head inside. A gouge ran down the front edge of the dashboard, over the missing radio console, showing the trajectory of a round. It seemed unlikely the shooter had been aiming for the occupants.

“And there’s something else,” Bluehorse said. He closed the driver-side door and then walked around to the passenger side. Joe followed. They squeezed between the piñon tree and the front passenger door. They crouched down. Joe looked to where Bluehorse pointed, at the now-closed driver-side door. The door’s plastic panel had long since been removed, and Joe could see the fabricated metal frame and mechanical components inside. A single bullet hole, round, jagged, had ripped into the frame at the base of the window, just below the pop-up lock lever. He hadn’t noticed them on his walk around the vehicle, but he had noticed that the paint had peeled at the top of the door and that rust had begun working its way down from that same corner.

“I don’t know the caliber,” Bluehorse said. “But it’s big.”

Joe walked around and examined the hole. After a moment he said, “Forty-five.” This bullet hole was interesting—and troubling. It was larger than the rounds in the windshield. He looked down. At first he thought he was looking at a brown carpet, but then he realized the entire floorboard was covered in rodent droppings. The rug had been removed.

“You want to stay involved with the investigation?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You’re going to have to keep quiet about what we do, even to your supervisors. Is that going to be a problem?”

Bluehorse hesitated. “The chief asked me to keep him updated.”

“You can keep him updated, but we’ll have to agree on what those updates will be. If that makes you feel uncomfortable, tell me now. I can’t have any more leaks to the press.”

“I don’t think the chief would leak to the press.”

“That’s the deal, Bluehorse. I like how you’ve handled it so far. I think you should be part of the investigation, since you’re the one who found the car, but it’s your call.”

“Are you going to bring out a crime-scene team?”

Joe shrugged.

“Okay. I’m in,” Bluehorse said, smiling. “But please give my chief decent updates, so I don’t lose my job.”

“Welcome to the team.”

“What’s next?”

“Well, we have no idea if the bullet holes are related to Edgerton’s disappearance. It could’ve been some hunters having fun.”

“What if it wasn’t?”

“That’s why we cover our asses and bring in an FBI evidence team.”

SEPTEMBER 24

FRIDAY, 12:49 P.M.

JONES RANCH ROAD, CHI CHIL TAH (NAVAJO NATION), NEW MEXICO

Officer Bluehorse watched Joe’s Tahoe disappear down the road. He couldn’t help but grin. He was on the case. Only a rookie and he was going to be working one of the biggest cases to hit the reservation since … since he didn’t know when.

He wanted to tell someone, but he didn’t know who. He’d have to wait until he got home tonight. He saw himself sitting around the dinner table with his folks, forking a few peas, offhandedly mentioning the investigation. Oh, by the way. That Edgerton case. The BIA wants me to work it.

He couldn’t wait.

But for now, he’d have to satisfy himself by telling someone else. He took out his cell phone.

“Chief, this is Officer Bluehorse. We just finished.” He told the chief about Joe’s inspection of the Lincoln, grinning the entire time. “He said I could assist with the investigation, if that’s okay with you, sir.”

His good mood soured slightly. “I’m not sure what his plans are, sir. He’s going to call me tomorrow.”

After he disconnected, he stood there for a bit, not moving, still flying high, but beginning to see the ground. Joe had given him a chance; he wouldn’t let him down.

He punched in his grandmother’s number.

“Shi másání,” he said. “I’m in Chi Chil Tah and was thinking of Shi chei.”

They talked a little about family and about why he hadn’t been out to see her the past couple weeks. He didn’t mention the case to her, though. She didn’t follow the news, and it would have taken too long to explain its importance. But he did have a reason for calling.

“Shí másání, do you still have any of Shi chei’s oak kachinas?”

SEPTEMBER 24

FRIDAY, 2:18 P.M.

EDGERTON FOR GOVERNOR HEADQUARTERS, SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO

For the past month, the two dozen volunteers who staffed Grace Edgerton’s campaign headquarters buzzed with the excitement of an impending win. The polls predicted it. Her staff echoed it. In four weeks’ time, Grace Edgerton would be elected governor of the great state of New Mexico. And she was ready. Ready to lead New Mexico to a prosperous future that would embrace the multiethnic population and leverage the state’s technological centers, the backbone of its economy. She would also protect the border, not to keep Mexicans from following their dream and coming to the United States, but to stop the flow of drugs and violence. Those were her campaign pledges. And any one of her volunteers there in the office would swear she planned to do just that. She loved New Mexico. To her, it was the Land of Enchantment.

But yesterday, things had changed. Brooding silence descended upon her headquarters. Volunteers spoke in hushed whispers as they stole furtive glances toward Grace Edgerton’s office and the battalion of senior staff dashing in and out. The change began right after Channel 13 reported her husband’s vehicle had been found.

In less than a month, voters would go to the polls and decide which lever to pull—or rather, which button to push. Her volunteers started talking about defeat. That morning, two had called in and said they could no longer volunteer because they had found jobs.

Now, Congresswoman Grace Edgerton rocked back and forth in her tufted high-backed burgundy office chair. That morning’s edition of the Albuquerque Journal lay on her desk. The photograph above the fold showed a smiling Arlen and Grace Edgerton, their hands joined and raised in a victory pose. Arlen’s first election, in 1986.

Gabriella Soyria Cullodena Sedillo-Edgerton began to cry.

Cullodena was her grandmother’s first name on her mother’s side, the Gilchrist side. A proud Scottish family. Her father, Gustavo Alejandro Sedillo, came from a wealthy Mexican family. Both sides opposed her parents’ union. But when Grace was born, their families put aside their ethnic differences and doted on their pequeño joya, their little jewel.

Grace’s parents lived in Matamoros, a city on the U.S.-Mexico border, across from Brownsville, Texas. But a few months before Grace was due, her mother moved to Brownsville and delivered her first baby at Mercy Hospital, or La Merced, as the locals called it, ensuring Grace’s birthright citizenship. Grace grew up attending the best private schools in America. Later she attended the University of New Mexico, which wasn’t the best, but it did have the largest Hispanic population in the country and was close enough for Gustavo Sedillo to check up on his only daughter. At age twenty-two, she met an older man, Arlen Edgerton, a transplanted blue blood from Massachusetts, who became a campus activist and her college lover. At age twenty-six, she was the wife of Congressman Arlen Edgerton, the beloved New Mexican, the celebrated liberal, and her political role model. At age thirty, she was Congresswoman Grace Edgerton. And now, at an age that she tried her best never to divulge, she would be Governor Grace Edgerton.

Her office door flung open. She wiped away a tear.

“We’ve got trouble.” Christopher Staples, her campaign manager, strode into the office, an invisible cloud of cheap aftershave in tow. He plopped his two-doughnut-a-day bottom onto the burgundy leather couch she kept in there for those long nights during the campaign. “Big trouble. Godzilla sequel–size trouble. King fucking Kong–size trouble. This is the shit you can’t foresee. The shit that can torpedo a run at the last minute.”

Her chest fluttered. “What is it?”

“This could sink us. Sink you.”

“Chris, calm down and tell me.”

“So close. So freakin’ close.”

“Chris!”

“Arlen’s vehicle was riddled with bullets.”

“Oh God.”

“See what I mean. A shitstorm is about to hit and stink up your campaign.”

“Oh God.”

“You can say that again.”

She whispered, “Arlen.”

Chris stared at her.

“I’m sorry,” he said, but his tone didn’t agree. “I shouldn’t have dropped it on you like that. But we need to move.”

Grace took a deep breath and wiped away another tear.

“Why?”

“Kendall called. There’s a Washington Post reporter already sniffing around, working the angle that you knew about the affair and maybe you put a hit out on your husband and that tramp.”

“Her name was Faye and she wasn’t a tramp and they weren’t lovers. I shouldn’t have to be telling you this. You’re supposed to be on my side.” She looked down at the paper on her desk. At the picture of her and Arlen holding hands. “Those rumors are old. No one cares about them now.”

“This is the Washington fucking Post. You know, the Watergate folks. They put the FBI to shame.” He shook his head in disbelief. “Damn it, Grace. Take your blinders off. Arlen’s disappearance never amounted to much back then because no one had any answers. No one knew what happened. Anything goes now. They could find the gun in your desk drawer, for all I know.”

She sprang to her feet. “What the hell do you mean by that?”

“Kendall’s concerned, and I don’t blame him. If he endorses you now, there can be blowback later. He wants you in office so you can return the favor when he announces his run for the White House. But you go up in flames with this, he gets burned.” He leaned his head back, pressing the palms of his hands against his eyes. “Shit. You may have been considered for the VP ticket. I so wanted out of this state. You know, I was even checking out condos in D.C.”

“Knock it off. I’ll talk to him.”

He dropped his hands and met her gaze. His expression suggested he was witnessing humanity’s fall from grace. “Look, I’m neither your priest nor your lawyer. I was hired to get you elected. If you had anything to do with it, I don’t care. But if you, by some wild chance now, do get elected and the feds come knocking at the governor’s mansion someday, perhaps it would be in your best interest to start planting a few seeds of marital discord. It might help you later. I get paid either way; just give me the word.”

“Let me make one thing perfectly clear. I love—loved—Arlen, and I want to know what happened to him, just like everyone else. And if you don’t believe me, then maybe you need to consider joining Percy’s camp.”

“Don’t think I haven’t.” Chris struggled to his feet. “And remember what I said. Marital problems make you sympathetic.”

SEPTEMBER 24

FRIDAY, 2:59 P.M.

BANK OF ALBUQUERQUE TOWER, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO

Joe parked in a no parking zone. He tossed his placard on the dash. The laminated card read FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY—FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT VEHICLE. He hurried into the building.

Inside, he scanned the tenant directory posted on the wall.

THE HAMILTON GROUP … 17th Floor.

He checked the time. He was late.

SEPTEMBER 24

FRIDAY, 4:37 P.M.

MICKEY’S BAR & GRILL, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO

On the drive over, Joe had received a call from Bluehorse. The Gallup newspaper had printed a story about Edgerton’s vehicle being found bullet-riddled.

With his finger, Joe wrote the words shit happens in the condensation on his mug of beer. He appraised his work. Andy Warhol had nothing on him. Pop art at its finest.

“Wanna talk about it?” Mickey Sheehan said as he sorted through the quarters in the bar’s register, forever on the lookout for rare coins.

“Not right now. I’m finding my muse.”

“Ask her if she’s got a sister.”

“You need a bingo partner?”

“One of my waitresses quit.”

Mickey started on the nickels. Joe watched. Back in August, Joe had been sitting on the same stool when Mickey yelled, “I’ll be damned. No P.” He repeated that a few times, slapping the mahogany bar top and laughing. He later told Joe that all the dimes minted in Philadelphia after 1980 had a P, designating the city. In 1982, the mint accidentally omitted the P from a small batch. Mickey’s dime would fetch a couple thousand dollars, though he’d never sell it. “I got a spot for it right next to my 1955 doubled-die penny.” Joe had no idea what a 1955 doubled-die penny was, but he appreciated Mickey’s enthusiasm, especially when he gave the bar a round of drinks on the house.

Mickey finished his coin hunt and limped to the other end of the counter to check on the only other customers at the bar, two men in suits and ties who huddled together and talked in whispers, as though they were discussing trade secrets. Maybe they were.

Mickey’s Bar & Grill had the feel of an old-time saloon. The walls were of wood panel and exposed brick, and the thick oak tables and chairs were covered with liberally applied coats of varnish. The place smelled of smoked ribs and frothy ale. War photographs decorated the walls. Mickey had served in Vietnam with the Screaming Eagles. He once told Joe how he’d earned his Purple Heart. “During the war—and don’t believe that conflict bullshit; it was a goddamn war—I was at Firebase Ripcord when the shit hit the fan. We was getting pounded by mortars. I jump in a foxhole and feel a sting on my right calf. I reach down to rub it, thinking I got nicked by a flying stone or something, and the son of a bitch is gone.” He looked Joe in the eye. “Now my foot powder lasts twice as long.” He’d winked then, but Joe had been too involved in the story to laugh or smile, or whatever the old war vet had expected.

Joe liked Mickey and he liked the bar. It relaxed him. He sipped his beer and enjoyed the relative quiet of pre–happy hour. Mickey would turn the music on around 4:30, sometimes Tony Bennett, sometimes something more current. And then the after-work regulars would start to trickle in, most sitting at the bar, a few grabbing tables for dinner. Joe knew the routine of the regulars. He’d become a member two years ago, ever since Christine’s …

He downed the mug and set it at the end of the counter, indicating to Mickey he wanted—no, needed—another. Mickey hobbled over, took out a fresh mug from under the counter, and filled it.

“Ready to talk?”

“Yeah. Just needed to get one down.”

“I’m listening.”

“Had a job interview today. I was late and it didn’t go too well. The guy was younger than my daughter.”

“Don’t worry about it. You got a good reputation and you know your shit. It’ll work out. But next time, don’t forget to shave.”

Joe stroked his face. Shit. Actually, he’d hadn’t forgotten. He just hadn’t bothered. Shaving was one of those things that didn’t seem so important anymore.

Mickey went on: “How’s Melissa?”

“Top of her class, as always. Just like her mom.” He took a swallow of beer, a long swallow. “Nothing like her dad. At least I can be thankful for that.”

“Snap out of it, Joe.” Mickey’s voice was serious. “I don’t mind your business. Hell, I appreciate it. But you got more going for you than coming in here and drinking by yourself every night. You’re still young—younger than me, anyway. Get out and meet people. Meet some women.”

“You’re a broken record, Mick.”

“See what I mean. You’re outta touch. They ain’t got records no more. You gotta say, ‘Mick, you sound like a skipping CD.’”

Joe smiled. “I don’t think anyone says that.”

“They should. ‘Broken record’ sounds old-fashioned.”

Joe wrote skipping CD in the condensation on his mug, wrapping the letters all the way around so they started and stopped at the handle. No, it didn’t have the same ring as “broken record.”

“We may have a prospect,” Mickey said.

Three women walked toward the bar. They didn’t look over. Joe knew two of them, Linda and Sue. Two very nice, and very loud, married women who came to Mickey’s a couple times a week to grab a drink and do battle with the bar’s sound system. They worked for a large development company down the street. Joe liked them because they were fun to listen to. He didn’t know the third woman, a blonde. She walked between the other two, laughing a nice laugh, a friendly laugh. Joe immediately liked her. She filled out her beige pants like roses fill out a bouquet—and she wore sensible heels. If she had been wearing high heels, he’d have pegged her as high-maintenance. Christine, his wife, had never worn stilettos, but she’d always had great legs and never needed the extra sculpting.

Joe returned to his beer. This time he wrote stilletto in the condensation, not sure how to spell it. He tried to remember if he’d ever written the word before. He didn’t think so. He couldn’t remember writing high heels, either.

Joe took another long swallow of beer. He was about to draw a high heel, when a woman spoke behind him.

“It’s only one l.”

Joe turned and saw the blonde standing next to him. She offered a smile. He turned on his charm.

“Huh?”

She pointed to his mug. “Stiletto has one l. Why did you write that on your mug?”

Joe had an answer, but not one that made sense. Oh, hi. I noticed you weren’t wearing stilettos, so I knew you weren’t high-maintenance. Why, no, I’m not crazy. Why do you ask? Instead, he lied. “Reliving my fifth-grade spelling bee. I got it wrong then, too.”

“You’d think you would have come to terms with that by now.”

“Some losses are harder to get over than others.”

“I’m sure.” Their eyes locked for a moment. “I came over to thank you for the drink.”

Joe searched out Mickey. The old bastard winked.

“Welcome to the neighborhood,” Joe said. “Linda and Sue are a lot of fun.” Lame.

“They are.” She leaned in and whispered, “But they’re so loud.”

“Loud? I never noticed.”

She laughed and held out her hand. “I’m Gillian.”

“Joe. Nice to meet you.”

“Would you like to join us?”

“No, I wouldn’t be great company tonight. And besides, I have a failed geometry test from ninth grade I have to revisit. Still can’t figure how I botched that one.” He drew a triangle on his glass.

“You’re funny.” She turned and went back to her friends. Linda and Sue both looked over and waved. “Hi, Joe,” they shouted almost in unison, but not quite. He waved back and placed his half-empty mug on the end of the counter. Mickey came over.

“She thanked me for the drink,” Joe said.

“You’re a real sweetheart.”

“Yeah, I surprise myself sometimes.”

“Another?”

“One more. I don’t want to ruin my nice-guy impression by staggering out of here.”

“Too late. Linda and Sue already know you. But I’ll see what I can do with the new girl.”

SEPTEMBER 24

FRIDAY, 7:23 P.M.

LOS DANZANTES, CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, DISTRITO FEDERAL, MEXICO

Cedro Bartolome swirled his glass of Chianti. He examined its legs, sniffed, and then took a sip. Plums and Mother Earth.

“Excelente,” he said.

The waiter poured wine for the other three guests.

Tonight was special. For the last three weeks, he’d been courting a new client for the firm, a conglomerate with sizable holdings in both Mexico and the United States. A few hours earlier, the conglomerate’s in-house counsel had notified him it had selected his firm, so he had called his wife, Daniela, and told her they would go out tonight to celebrate. Then he invited Ernesto and his wife. Ernesto was one of Cedro’s five partners at the firm, and he rarely refused an opportunity to enjoy good food and spirits.

“Have you been following the news in America about Edgerton?” Ernesto asked in Spanish.

Almost two decades had passed since Cedro had last heard the name.

“It’s not good,” Ernesto said. “The authorities found his car. They could start asking you questions again, maybe put some pressure on the firm. We should be ready.”

Cedro sipped his wine. He detected the pedestrian flavor of sour berries.

SEPTEMBER 25

SATURDAY, 9:11 A.M.

JONES RANCH ROAD, CHI CHIL TAH (NAVAJO NATION), NEW MEXICO

It took Joe a few minutes to find Bluehorse’s trail, two tire tracks turning north off Jones Ranch Road. He got out and stuck a small orange flag into the clay by the path. Then he climbed back in his vehicle and drove into the tree line.

The way was rough. He switched to four-wheel drive. As he weaved around trees, he glanced occasionally in his rearview mirror, catching the brilliant rays of sunlight that penetrated the thin canopy and gave the clouds of dust behind him a surreal glow, as though he were passing through a magical gateway, a rift through worlds. Perhaps he was. Many have described the Navajo Nation as a mystical place, a place where superstition and the substantive world fuse into a new reality.

The trail ended in a small clearing, perhaps fifty feet at its widest. He parked next to Bluehorse’s unit, then got out. They shook hands.

“The others are on their way,” Joe said. “Should be here by ten.”

“I called the chief a few minutes ago. He said he was upset I didn’t know about this yesterday.”

Joe had asked Bluehorse not to tell his chief the FBI would process the vehicle today. He hadn’t wanted any press showing up at the road. He’d suspected the chief was the one behind leaking the story about the bullet holes.

“Don’t worry. You’ll have enough to update him on after we finish here.”

“Did you tell your boss?” Bluehorse asked.

“We don’t talk much.”

SEPTEMBER 25

SATURDAY, 9:30 A.M.

THE CONSTITUTION ROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C.

Kendall Holmes touched his lips to the gold-rimmed china cup and sipped the Earl Grey tea, letting it bathe his palate. The soft bergamot tang excited his mouth yet calmed his body. He relaxed into the oversized poppy-colored leather chair in the waiting lounge of the Constitution Room, an exclusive power dining spot in D.C. Anyone who was anyone kept this number on speed dial, and anyone who mattered had standing reservations. More legislation was finalized here than on the Senate and House floors combined. And, to be honest, the Constitution Room offered the proper atmosphere to run a country, rivaling the White House in elegance and grandeur—no, exceeding the White House. On his last visit to the home of the supposed most powerful man in the free world, he had noted how shabby the place looked. The radiators begging for paint, the plaster walls bulging and out of shape. Unacceptable. He might have an opportunity to do something about that in a couple of years. The Constitution Room, however, was flawless. Even the silver and crystal chandeliers hanging from the twenty-foot ceiling gleamed with a perpetual polish. Never a speck of dust or the taint of tarnish. More important, these dangling islands of light cast the perfect illumination. As with every decision inside the Beltway, it was likely the product of a three-hundred-page report prepared by a consultant who had studied the exact number of lumens required to attract venerated statesmen—as well as the reviled.

Holmes looked over at the waiter, who stood off to the corner, visible to the eye yet distant to the ear. Eavesdropping does not attract politicians. Kendall held up his tea and nodded, indicating it was a fine cup. The young man returned the nod with a quick smile. The waiter was new. Holmes would develop him over time. Sources were important. A waiter at the Constitution Room was gold, maybe even platinum. A tidbit here, a morsel there. Holmes called it “mosaic intelligence.” Individually, the pieces were meaningless, but together, they made a picture. That was the purpose of his meeting this morning. To gather intelligence. But with caution.

He checked his watch, a Blancpain. Nine-thirty-two. The roman numerals circling the face appeared blurry. He’d stayed up late last night, leaving in his contacts, something he rarely did because his eyes were sensitive. The Edgerton mess was not only disrupting his usual calm but also his sleep. His phone vibrated, a text from his head of security—and longtime bodyguard—who waited in the lobby. His guest had arrived.

A minute later, Helena Newridge, a journalist for the Washington Post, waddled through the lounge, her head bobbling about, no doubt spying for gossip. The bulky jewelry around her neck and wrists gave off a rattle as she walked.

Holmes hid his disgust. “Ms. Newridge, over here.”

She sat down across from him. “I haven’t been here in a while. Budget cuts—unlike the government.”

He gave her his win-over laugh, one he’d perfected for his community-outreach meetings with constituents. “Allow me to grant you an appropriation. This will be my treat.” He slipped on his D.C. smile.

“You’re very smooth, Senator.”

“I enjoy people.”

She gave a smirk. “Uh-huh.”

“But before we begin, we have to agree on the terms. Yes?”

“We covered that on the phone.”

“We did, but for my own peace of mind, I would like to confirm our arrangement. You’re new to certain circles, so I need to know if you can be trusted to keep a confidence.”

“It’s my bread and butter.”

“I’m sure.” He smiled, showing his laser-whitened dental work, and his slightly pointy canines. “So we agree to background only. No quotes and I am not to be mentioned in the piece, correct?”

“Correct.”

“And no recording.”

She looked disappointed. “Fine, no recording.”

“Okay, shall we eat now?”

“Sure, as long as we talk, too.”

SEPTEMBER 25

SATURDAY, 9:56 A.M.

JONES RANCH ROAD, CHI CHIL TAH (NAVAJO NATION), NEW MEXICO

Two midnight blue Suburbans pushed through the tree line. The first parked beside Joe’s vehicle. Behind the wheel was Andi McBride. She burst from her vehicle and strode up to Joe like a hungry bear greeting a hiker.

“What do you have, Joe? And I hope we aren’t parked in the scene.”

“Hello to you, too, Andi. How have you been? How’s the family? Go anywhere interesting on vacation this year?”

“Cut the crap. You know we’ve got all day to catch up. But if you want to know, I missed my jujitsu class this morning, so I haven’t relieved all my stress”—she looked Joe up and down and cracked a knuckle—“yet. I got food poisoning on my cruise and was sick for three days. And if I don’t get back to Albuquerque by six, my ex- is going to go apeshit, because I promised to take Pauly to the movies tonight. Other than that, I’m great.”

Bluehorse, who was standing next to Joe, took a step back.

“Happy to hear it—I mean that you’re great,” Joe said, trying to suppress a smile.

“You doing all right?”

“My boss is on my ass, the job is telling me to retire, and there’s a vehicle just over there”—he gestured to the east—“that’s probably going to be a giant hemorrhoid. And I have another tuition payment due in two weeks. Other than that, I’m great.”

“Happy to hear it—about you being great, I mean.”

They shook hands.

“All right. Give me the nickel summary and skip the Edgerton part. I’ve been watching the news.” She held her pen and clipboard at the ready.

Joe let Bluehorse tell about his find and the bullet holes. As he spoke, two more agents joined them, one male and one female. The female agent was reserved and stayed off to the side of the group, filling out what Joe guessed was a crime-scene form. He recognized the man.

“It’s Joe, right?” said Mark Fisher, a young candlewick of a man constantly burning nervous energy. “We did the Lujan case together in Sandia.”

Joe recalled the case. A fired railroad worker went home and lodged an ax in his son’s head because the teen had left a carton of milk on the counter to spoil. The drunken father had wanted a bowl of cereal.

“It’s been a while, Mark.”

“I read the father got seventeen years. Good job.”

“Thanks,” Joe said. “We appreciated your help with it.”

“Did they set a date for your retirement party?” Andi asked Joe.

“Not yet. Stretch is on it, though.”

Andi assigned Mark to evidence collection, and the other agent to photos and sketching.

Before they started, Mark went back to the Suburban. He returned a few minutes later carrying a long black plastic case, a camera bag, a camo backpack, and a tripod. Then they all followed Bluehorse to the once-forgotten hunk of metal sitting a short distance in the woods.

The milky white paint of the Lincoln glowed rather than radiated from the morning sunlight, giving its edges a fuzziness that seemed to ripple as though alive. The group circled the plundered vehicle. Criminologists suggest that stripping a vehicle is an act of vandalism, representing a breakdown of law and order, society’s failure at self-policing. Joe saw it as a symptom of social cancer. The doers, like mutated cells, ate away at a neighborhood, spreading, infecting others, until the mass got so large that the community collapsed. He was sure some of these cancerous cells lived nearby. They had taken what they could from this vehicle over the years, rather than reporting it to the police so a proper investigation could have been completed back when the congressman went missing. Now Joe had to deal with it.

Bluehorse showed them the bullet hole in the driver-side door and offered his theories.

“Let’s see you work some magic, Mark,” Joe said. He didn’t feel hopeful, but he knew he had to cover every angle in order to uncover any possible clue.

“That’s why I get paid the big bucks.” Mark passed out breathing masks and gloves to Joe and Bluehorse as the other agent took photographs of the vehicle and the surrounding area. Over the next hour, they shoveled out the rat droppings from inside the vehicle and ran metal detectors over the piles, looking for slugs or shells or anything else out of place that might potentially be a clue. They found nothing other than nuts and bolts, bottle caps, and metal brackets.

When they finished, Mark climbed into the vehicle to examine the bullet holes in the windshield and door. He and the female agent photographed and measured them all. When they were done, Mark focused on the door, placing his left cheek to the hole. He peered through.

“Oh yeah. This is going to be fun.”

Joe could hear a slight giddiness in his voice. He knew evidence guys—and gals—got excited by challenges at a scene.

“I feel pretty confident we can find this round,” Mark said. “No guarantee, of course. But definitely possible.”

Mark went to work. He opened the long black case and extracted a small box, a long metal rod, and a tiny tripod, all of which he handed to Bluehorse.

“Hold on to these until I get inside.”

Mark slid back inside the vehicle.

Bluehorse handed Mark the equipment.

Mark placed it on the battered dashboard, opened it, and withdrew several small white plastic cones with holes running lengthwise through them. He held them to the bullet hole in the door, inserting each one gently, and then removing it to try the next, searching for a cone that fit snugly into the hole and was oriented in the direction the round would have traveled. He seemed to find the one he wanted and placed the others back in the box.

He grabbed the long rod and pushed it through the bottom of the cone, sliding the small white plastic halfway down its length. Angling the rod, he inserted it through the bullet hole until the cone seated. He wiggled the rod assembly a few times until he appeared satisfied. He looked up. The rod pierced the driver’s door like a magician’s sword through a magic box.

“Now for the angle finder,” Mark said, more to himself than to the others.

Mark held a yellow plastic device at the back end of the rod. He read the dial and then made a notation on a small notepad he pulled from the cargo pocket of his pants.

Joe was absorbed by the process. He’d seen this technique used only once before, in an accidental shooting involving elk hunters.

Mark extended the legs of the tripod so they touched the now somewhat clean floorboard and then placed the rod in a small U-shaped clip at the tripod’s top. After making a few adjustments, he leaned back and appraised his work.

“This is not going to be perfect, but it’ll give us a good search vector.”

“You got my attention,” Joe said. “What’s next?”

“Do you have any idea if the vehicle was moved over the last twenty years? Maybe pushed or towed? Even a few feet?”

Because of the car parts under and around the vehicle, they didn’t believe it had been moved. It appeared to have been stripped in place.

“There are three unknowns we’re dealing with here,” Mark began. “First, was this vehicle parked here when the shot was fired? Second, was there anything on the outside of this door that could have intercepted the round and subsequently changed its direction, like a person or a tree that’s been cut down since? And third, was the round an ice bullet and has it since melted away?”

Bluehorse looked surprised.

Joe laughed.

“Okay, we only have two unknowns. But one of these days someone will try something tricky like that, and I’ll be ready.”

“I pity the fool,” Joe said in a poor imitation of Mr. T.

Mark and Bluehorse both looked at him, heads cocked.

“The A-Team?” Joe waited for a response. Nothing. He shook his head. “Young’uns.”

Mark went on: “So we could do an entire three-part mathematical equation to calculate the round’s time aloft, maximum height, and horizontal distance traveled, taking into account wind resistance and the Earth’s rotation, but…”

Bluehorse bit. “But?”

“But we don’t know the round’s velocity, and without that, I can’t do the calculations.”

Dramatic pause.

Bluehorse bit again. “Oh.”

“So we’re left with one option. The string technique.”

No one said anything.

Mark continued, possibly a little disappointed by the lack of response. “I connect a laser to the rod and shoot out a beam for about two hundred yards or until something stops it—something that could have stopped a round. That’s our trajectory. Then we run a string from here to that point and use a metal detector along the string’s path. If the shot was fired from this vehicle while it was sitting here, and if my angle of travel is correct, the round should be within five to ten feet on either side of that string.”

Bluehorse clapped his hands together. “I’m game.”

“Let me make two disclaimers. First, the car is at a lower angle because the tires are gone. Second, if my angle of travel through the door is off, or if the car shifted to the side over the years, that round may not be in our search area.”

“Fair enough,” Joe said.

“Let’s find ourselves a bullet.” Mark rifled through the little black box on the dash and pulled out a small penlike tube. He placed it at the back end of the rod and screwed it to the tip, making slow, careful twists, as though he were assembling a bomb. When it was connected, he checked the angle finder again and made an adjustment to the tripod.

“Bluehorse,” Mark said. “In my backpack you’ll find several sheets of white card stock. Grab a piece and hold it in front of the rod.”

Bluehorse unzipped the bag.

A gunshot shattered the relative quiet of the woods.

SEPTEMBER 25

SATURDAY, 11:43 A.M.

RESIDENCE OF WILLIAM TOM, FORT DEFIANCE (NAVAJO NATION), ARIZONA

William Tom dipped the last piece of wheat bread into the mixture of egg yolk and green chili. As he lifted the soaked morsel to his mouth, he felt the light patter of liquid on his shirt. He shoved what remained between his fingers into his mouth and used his forefinger to catch the runaways on his stretched and yellowed T-shirt, smearing them into a single large stain. He called out to his wife.

“Chllarrr!” Swallowing, he tried again. “Char!”

“Ha’átíí?” Charlene replied, annoyance apparent in her voice. She was sitting in the living room, watching cartoons.

“I need a new shirt.”

“Biniiyé?”

“Because I got a stain on it.”

“Biniiyé?”

“Damn it! I need a new shirt.”

“T’ah.”

“Stop watching that shit and get me a shirt.”

“T’ah.”

“You’re a disgrace to your Navajo ancestors, woman. Don’t speak the language if you can’t live by the traditions.”

“Go get it yourself, old man,” she said, switching to English.

He pushed himself away from the kitchen table, his wheelchair sliding easily over the linoleum floor. He wheeled into the living room, looking at the back of Charlene’s head as he went. At forty-two, she was twenty-five years his junior. Her liver was probably older than his, the way she drank, but that was probably all. She would surely outlive him.

He never touched alcohol and always ate well, but that hadn’t made a difference. His whole body had given up on him a decade ago when he’d developed type 2 diabetes. He’d lost his right foot from a complication eight years ago. Then they took his lower leg. Last year, they took his thigh. Two months ago, a sharp tingling started to come and go in his left foot, but he kept that quiet. He’d lost most of the sight in his right eye and had been surprised that the doctors hadn’t offered to cut that out, too.

In the bedroom, he maneuvered himself to the dresser and opened the middle drawer. The bottom three drawers were his, the top three hers. He pulled out a once-white T-shirt, now a sickly shade of piss.

William had left the Navajo reservation at the age of ten to attend boarding school in Vermont. He stayed there until he was eighteen, with few trips back home during those years. He went on to study archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania, and only after graduation did he return to the reservation. He wanted to bring his education back to his people. He was appointed as director of Navajo Antiquities, a department of government that safeguarded the Navajo Nation’s cultural history, and a place where he tried to make a difference. But that position offered little opportunity. So, many years later, he ran for president of the Navajo Nation. One requirement for presidency was fluency in Navajo. Because he’d left the reservation so young, he’d never mastered the language. But when he wanted something, he did what was needed to attain it, so he’d studied hard for most of a year to gain fluency. He was elected in 1991, the same year he met Charlene, his third wife. His first two wives had become too traditional for him. Now, in his later, wiser years, he wished Charlene would become more traditional.

He pulled off his stained shirt and placed it on his lap. It took him a little time, but he put on the new shirt and adjusted it down around his back. His body had grown weak these last few years and simple tasks like getting dressed tired him quickly. He wheeled over to the laundry basket. The clothes were piled high, overflowing onto the floor. The pile would grow much larger before Char got around to doing the wash. He rolled up the soiled shirt and was about to toss it on the mound, when he saw a pair of her panties on top.

She had gone out the night before and hadn’t returned home until after two, waking him up when she stumbled through the front door. She’d gone to Gallup, she’d said, with a few friends and had some drinks at the American Bar. When he asked her how she had gotten home, she said a friend drove her. She would not name the friend. He looked at the panties now, tempted to examine them for evidence of infidelity, to prove once again that she was cheating on him. But he realized it wouldn’t do any good. He’d confronted her before, and she hadn’t denied it.

“What do you want me to do?” she’d said. “I’m a woman. I’m young. You just want to sit home and read your stupid books. I can’t do that.” She hadn’t spoken Navajo that time.

That was the first of a dozen arguments they’d had about her sleeping around. His family would tell him from time to time that they’d seen her here or there with this guy or that guy. He’d tell them to mind their own business. Once, he told his brother, “What am I supposed to do? I can’t run after her.” He’d stopped driving when he started to lose his sight, so he just sat at home like a good invalid. He still wielded some power on the reservation, still had some friends—still had some enemies, too. He could find someone to pay a visit to one of her friends, but that would imply he still cared. He didn’t. Let her have her fun. He wouldn’t be around much longer. Didn’t want to be around much longer. Living was too much work now. Work and pain. As for him, they could put him in the ground tomorrow. A relic to be uncovered sometime in the future. A fitting end for an archaeologist.

He tossed his shirt on top of the pile and spun his chair around. He wheeled through the living room, out the front door, and onto the porch.

The Navajo Times lay there, wrapped with a rubber band. He bent and scooped it up, the effort making him breathe hard. He coughed. He smelled the air. The sage was strong and clean, energizing. As president, he had often told his constituents how much he loved the high desert and beautiful mesas, and how blessed the Navajo were to occupy their ancestral lands between the four sacred mountains. But after leaving office, he started telling the truth. He missed Vermont. He missed the deep greens and the vibrant colors of the Northeast. And more important, he missed the world-class hospitals there.

He sat for several moments, enjoying the warm sunshine. Then he pulled off the rubber band and unfolded the paper. He focused on the top story. “Clue to Congressman Edgerton’s Disappearance Found on Reservation.” His hands shook as he read.

SEPTEMBER 25

SATURDAY, 11:43 A.M.

JONES RANCH ROAD, CHI CHIL TAH (NAVAJO NATION), NEW MEXICO

Joe dropped to one knee, gun drawn. The sound of the shot had been close. Too close. He checked on the others. Bluehorse knelt by the fender. Mark’s head eased up to the driver-side window from within the car.

Joe scanned the woods. Who the hell was shooting? And what were they shooting at?

“Police! Stop firing your weapon!”

Another gunshot roared.

It came from the east.

Joe and Bluehorse moved behind the vehicle.

“Police! Stop shooting!”

Silence.

“Get out of there, Mark.” Joe said.

Mark crawled through the passenger door on his hands and knees, staying low, below the dash.

Bluehorse pointed in the direction of the shooter. “Maybe forty yards.”

“Sounds like a shotgun,” Mark said.

Joe swept his weapon across the tree line.

“Andi,” Joe shouted over his shoulder. “You all right?”

Her voice came back immediately. “Right as rain!” She and the other agent were a little ways back, crouched behind trees. “Hunter?”

“Probably,” Joe said.

Another gunshot.

“This is the police! Stop firing your weapon!”

“What do you want to do?” Mark asked.

“Let’s move to contact before this asshole sends one our way,” Joe said. They made a quick plan. He would head toward the shooter. Bluehorse and Mark would flank right. Andi would stay behind to secure the scene, along with the other agent.

He had worked with Andi many times over the years and would have preferred to go into the woods with her, but sometimes a situation dictated differently. Thankfully, Bluehorse and Mark both seemed more than capable of handling themselves. Some officers he’d encountered would have given him cause to worry. And he guessed his own squad may have felt that way about him.

Another gunshot went off.

“Let’s go.”

They sprinted for the tree line.

Joe’s adrenaline surged. Twenty steps and his heart was already hammering. His thoughts turned dark. Would he have a heart attack or catch a stray bullet from some yokel shooting cans? With less than ninety days till retirement, what the hell was he doing out here? This was the type of story cops shared in the locker room. Hey, you remember old Joe from BIA. He was only ninety days out when …

He ran on, trying to clear his head. When was his last conversation with Melissa? Wednesday? Had he told her he loved her? He wasn’t sure.

Another gun shot. Much louder. Closer. Like he was on the range without ear protection. He yelled for Bluehorse and Mark to hold up. He needed to get his bearings.

“See anything?” he asked.

Nothing.

He yelled again into the woods.

No answer.

Another gunshot. He zeroed in on the sound and rushed forward, jumping over sage and rabbitbrush. He smelled cordite in the air. That and freshly turned soil. Maybe a little burned wood, too.

He saw a figure no more than two dozen steps ahead of him. It appeared to be a man. He held a double-barreled shotgun, his back to Joe.

“Police! Stop firing!”

The man held the gun to his shoulder. It pointed down to the ground, to a fallen oak in front of him. Another round went off. Deafening. What the hell was he firing at?

Joe slowed, gun at his chest, muzzle lowered. He didn’t expect to use force, but the man had a firearm. Bluehorse and Mark moved up from Joe’s right. Good. Less chance of cross fire.

“Police! Stop firing!”

The man made no movement to indicate he’d heard the command. Instead, he broke the shotgun open and began to eject the two shells. Joe ran up behind him. With his left hand, he grabbed the man’s wrist, disabling the hand that held the shotgun. The man turned and let out a startled yelp. Joe was glad the man hadn’t dropped right there from fright. He was old enough. The warranty on his heart had surely expired a decade earlier. From the deep lines in his face and his urine-colored eyes, wide now from surprise, Joe guessed the old man had watched eighty pass him by a few years back. Hell, maybe even ninety, from the looks of his barren gum line. How had this decrepit old soul been firing a shotgun?

Bluehorse and Mark came to stand next to Joe.

They all looked down at the hole in the ground under the oak. A burrow.

The old man stared at Joe and then at Bluehorse. He gave Bluehorse’s uniform the once-over.