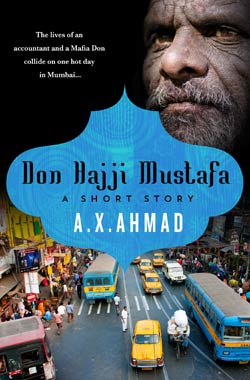

In “Don Hajji Mustafa” by A.X. Ahmad, a humble and desperate accountant meets an international crime boss on a hot day in Mumbai that will change his life.

In “Don Hajji Mustafa” by A.X. Ahmad, a humble and desperate accountant meets an international crime boss on a hot day in Mumbai that will change his life.

It is just five in the morning but the desert sun is already a ball of fire.

Mahmood Momjee stumbles onto the flight from Dubai to Mumbai, laden down with bags, sweat fogging his bottle-thick glasses. From behind, his wife Zeenat gives him a shove. She says, “Oof, Mahmood, get a move on, you’re holding up the whole bloody line.”

A man sitting alone in first-class hears Zeenat’s voice and looks up sharply. Mahmood’s skinny arms quiver with the weight of five duty-free bags of perfume, while his wife clacks empty-handed behind him in her lacquered red high heels.

The man in first-class raises his eyebrows questioningly, as if to say, You let your woman treat you like that?

Mahmood smiles weakly and shrugs, What can I do? Then he stops and stares.

The man is perhaps fifty, with dyed black hair and intelligent, hooded eyes set in a thickened face. He wears an expensive gray silk suit, and his hands rest awkwardly in his lap, covered by the tent of a glossy Vogue. But the magazine has shifted a little, and underneath, his wrists are visible. They are handcuffed tightly together, the silver bracelets gleaming in the early morning light.

The man sees Mahmood looking and smiles, a smile like a grimace. Mahmood ducks his head and hurries into the economy cabin, Zeenat huffing behind him.

As Zeenat settles into a window seat, Mahmood pulls a newspaper from one of the bags. A large headline screams, “DON HAJJI MUSTAFA EXTRADITED FROM DUBAI”, and underneath is a picture of the Don, a younger version of the man in first class: he was less jowly then, and his arm was draped around the shoulder of a bosomy Bollywood starlet.

Mahmood turns to his wife, his thin face flushed with excitement. “Zeenie, that man in first class, that was Don Hajji Mustafa, did you see today’s paper?”

But Zeenat isn’t interested. She is angry, and the small diamond stud in her nose glints with reflected light. “Really, Mahmood, I don’t know why you’re making all this bloody fuss, that man is just a common criminal. Here’s my passport. Put it away.”

He takes her blue-and-gold Indian passport, and gasps. Its cover is all warped, the ink on the inside pages running like mascara.

“What happened to it? In God’s name, are they even going to let you into India with a passport like this?”

Zeenat is busy twisting up her long auburn hair and slipping a sleeping-mask over her face.

“I must have left the damn thing in my bag when I went swimming. Just bribe the immigration people in Mumbai, everyone knows they’re corrupt. That’s what Daddy would do. Now don’t disturb me, I’m very tired.”

She tucks a pillow under her head, and instantly falls asleep. Mahmood takes off his sweat-smudged glasses and wipes them in his shirt, sighing deeply.

It’s all very well for Zeenat’s father to go about bribing people. Ali Joojebhoy is an old-style Mumbai businessman who turned his dried-fruit business into an international corporation, using a judicious combination of hard work and tax evasion. Mahmood is just a simple accountant who has lived outside India for many years; he has absolutely no idea how to bribe the greedy, khaki-clad immigration officials in Mumbai. Does he simply hand them the money, or is there some hidden protocol?

Whatever it is, he must get it right, because there is no time to get Zeenat a new passport. After spending the day in Mumbai with her father they’re taking an evening flight to Thailand. It’s their first wedding anniversary, and Mahmood has booked them into an expensive beach resort, the kind where a drink with an umbrella in it costs twenty dollars.

Mahmood looks over at his wife. Asleep, she seems at peace, her long dark eyelashes casting soft shadows on her round cheeks; there is no trace of the woman who has cried for the entire first year of their marriage. Mahmood wonders for the millionth time why Zeenat’s father had chosen him for an arranged marriage. The Joojebhoys are high-society Mumbai millionaires, and Mahmood is just a lowly bank clerk in Dubai. True, there are few eligible, fair-skinned boys in their Khoja Muslim community, but still… Why him?

To distract himself, Mahmood glances down at the newspaper in his lap, and the Don’s dark eyes stare back. He reads the article: “In an unprecedented show of cooperation, the Dubai Government today announced that Raouf Ameer Mustafa (AKA: ‘Don Hajji’ Mustafa) is being extradited to India. The title ‘Hajji’ was bestowed upon him when he completed the pilgrimage to Mecca. The title ‘Don’ he brought with him when he fled from Mumbai to Dubai a decade ago, wanted by the Indian police for gold smuggling. Mr. Mustafa has kept a low profile in Dubai all these years, operating as a legal businessman, but an international investigation has found that he is doing business with countries on the terrorist watch list….”

The poor bastard, to get deported like this.Dubai is full of crooks, has always been a grey zone with money flowing through, and no questions asked. Fertilizer from Iran is sold to Sudan, polyester trousers from Eastern Europe make their way to Libya; the money is routed through Azerbaijan or Malaysia, and everybody goes home happy. But now the Americans have declared their ‘war on terror’, and what used to be normal business practice is suddenly terrorism. Under these standards, half of Mahmood’s customers at Dubai Bank would be criminals.

There is the whine of engines and the plane taxis down the runaway, hurtling into the air. Mahmood sees the glass skyscrapers of Dubai disappear and the plane heads out over the glittering Arabian ocean, flying straight as an arrow to Mumbai.

* * *

The smell of India assaults Mahmood the moment he steps into the immigration hall: dust and sweat mixed in with the faint, pungent odor of toilets.

A plump immigration official is sipping tea from a cracked cup as he reaches for both their passports. He freezes when he sees the edge of a hundred dollar bill protruding from Zeenat’s warped booklet.

“Aare! What is this? This passport is all damaged and whatnot. Are you trying to bribe a government official?”

Mahmood’s voice takes on the half-whining, half-pleading tone he uses when faced with bureaucracy. “Sir, there is a little problem, but maybe, if you can overlook it…”

Just then there is a commotion. The Don emerges from the gate, hands still handcuffed, suit jacket draped over his shoulders like a cape. He is flanked by armed policemen who have the nervous air of bodyguards protecting a celebrity. A flash goes off and reporters shout questions at the Don, but he just smiles his grimacing smile and saunters through the airport.

The immigration official is staring, too. Then he remembers what he is doing and turns to Mahmood. “Take back your filthy money. You’re lucky I don’t arrest you.”

He stamps both of their passports with a thud. The ink is still wet when he returns them: Mahmood’s passport has the usual entry stamp, but Zeenat’s says ‘DAMAGED -NOT VALID FOR TRAVEL’ in large red letters.

Mahmood groans, and turns to appeal, but the official has ostentatiously turned away. Zeenat stares hard at Mahmood, tosses her hair, and heads through the exit, disappearing into the crowd. He struggles after her, pushing through knots of beggars, to find her standing with her father, a chauffeur-driven silver Mercedes idling behind them. Five-foot four, with a few painful strands of hair combed across his bald head, Ali Joojebhoy holds his daughter at arm’s distance and examines her lithe form, his proud smile saying it all: I may be from the bazaar, but look at what I have created.

Then he leans forward, taking in the dark circles under Zeenat’s eyes, the acne that has marred her once-pearly complexion, and starts to mutter under his breath.

Sighing, Mahmood heads towards the pair.

* * *

The air-conditioning in the Mercedes is ice-cold. Mahmood, sitting up front next to the driver, feels his damp shirt turn clammy.

Zeenat is talking loudly in the back. “Papa, it’s so good to be home. This Dubai is such an awful place. There is nothing to do there. All people do is have affairs with their Filipino maids. There’s no culture. And to make everything worse, this silly little man at immigration said my passport was ruined, and now I need a new one and Mahmood tried to give him a hundred dollars, but…”

Joojebhoy leans forward. “Mahmood did what?”

“Sir, I tried to bribe the man, but I think I got an honest one-”

“You fool! You don’t just shove money at them, you talk about the ‘expediting fee’. Then you pay the man sitting in the corner. Don’t you know anything?” Joojebhoy sits back, his trousers making a sucking noise on the leather seat. “This is a mess. The police, I can fix. I can even get the government to reduce income tax. But those immigration people, oh, they’re impossible.”

The back of Mahmood’s neck burns with shame; he’s never been spoken to so rudely. He knows that as the poor son-in-law, he’s in no position to talk back, but before he can help it, he reacts.

“Sir, don’t worry. I will take care of it. I have contacts in Bombay.”

“You? You have contacts?” Joojebhoy smiles, showing yellow, shark-like teeth.

“Yes, sir, I will fix it.”

“We’ll see. But I don’t think you’re going to make the evening flight to Thailand. I think you will be staying in Mumbai for a while.”

Mahmood thinks of spending the weekend in Joojebhoy’s vast, marble-clad mansion, and looks frantically out of the window. Just then, a slum dweller walks onto the road, drops his pants, and squats over an empty drain, his bony bottom pointed at Mahmood.

Welcome to Mumbai.

* * *

The noon air is shimmering with heat. Mahmood is alone in a taxi and he can smell each passing neighborhood: fish frying at Kemp’s Corner, the brine of the sea along Breachcandy, the fermented tang of garbage at Hajji Ali. He recognizes the smells, and the ocean looks the same, but all the rest has changed so rapidly. The old mansions and bungalows are being replaced by high-rise buildings, and the old bazaars are being bulldozed to make way for shopping malls with mirrored carapaces.

Money has always ruled Mumbai, but it is different now, more blatant. In the socialist years there was nothing to buy, so people remained contented. Now there are things everywhere, and shiny-lipped women on giant billboards sell color TV’s, washing machines and cars. People want it all, right away, and the old, tolerant languor of the city has been replaced by a sullen discontent.

Mahmood feels a pang of homesickness for the peeling, shabby city he had grown up in, for the tiny two-room flat he had shared with his father. Back then, he couldn’t wait to escape from this hot, smelly city, and live an air-conditioned life in Dubai. He’d never dreamt that one day he would return here, married to the daughter of a rich Mumbai businessman.

It was old man Joojebhoy who had contacted Mahmood with the marriage proposal. Mahmood had been hesitant, wondering why he’d been chosen, but then Joojebhoy had sent him a photograph of Zeenat. She was as pretty as a Botticelli painting, with shining, liquid brown eyes, long, glossy hair, and a curvy figure. Mahmood was smitten, and they were married with great pomp in Mumbai, and within three months Zeenat was his, arriving in Dubai with many suitcases and a large dowry in cash.

She’d wept loudly every night for the first three months, and a year later still slept in a separate room, and sobbed herself to sleep. Embarrassed, Mahmood had hidden this fact from his friends, telling himself that it was a huge adjustment for her, that she would eventually come around. After all, an arranged marriage united two strangers, and it took time for trust and intimacy to grow. He tried to cheer Zeenat up, renting a flat in the fashionable Jumeirah district, and furnishing it with modern, tubular steel furniture, but Zeenat remained inconsolable. She shut herself up in the darkened apartment all day, ate boxes of milk chocolate and watched again and again Hindi movies from the seventies, in which heroes wearing bell-bottomed trousers sang songs about unrequited love. Her beautiful cheeks became marred with acne, her long hair hung limp and lackluster, and she began to put on weight at an alarming rate.

The taxi has now crossed into the run down part of Mahim and Mahmood can smell open drains; it seems that the poor in Mumbai have remained in the same condition. He alights outside the police station, a brick fortress from British times, complete with crenellations and barred windows.

The lobby inside has rows of hard wooden benches and the dark-green paint on the walls is blackened by human contact. Mahmood remembers coming here years ago with his father to visit Captain Nazeem, a distant relative. Chain-smoking Nazeem knows everyone in the city, high and low; with any luck, he’ll have some contacts in the Passport Office.

The duty sergeant is seated at a high desk, the bulletin board behind him covered in rustling, yellowed notices. When Mahmood asks for Captain Nazeem, the cop looks at him with bored, piggy eyes, and asks what business he has with the Captain.

“Personal business. We’re related.”

“Well then, you’ll have to go to Matunga.”

“Matunga? But this is Captain Nazeem’s precinct.”

The Sergeant’s face creases into a big smile. “Matunga graveyard, that is. Nazeem died of lung cancer last year. If you’re related, you’d know that, right?”

The cop’s hooting laughter follows Mahmood as he turns away. Nazeem, dead. That’s the end of that. He can clearly see old Joojebhoy’s pinched, scornful face.

Mahmood’s glasses are streaked with sweat and he stops at the doorway to wipe them in a corner of his shirt. A jeep roars up outside and two policemen—high-ranking officers in peaked hats—walk into the police station, escorting a prisoner between them.

As they pass by, Mahmood puts on his glasses and Don Hajji Mustafa swims into view. His suit jacket is gone, his white shirt is torn and dirty, and purple bruises mark his bare wrists.

The Don pauses for an instant, a flicker of recognition in his eyes. As the police officers drag him away, he gives Mahmood a quick smile, showing clenched teeth.

The three men disappear into a room across the lobby. Its iron door clangs shut, and Mahmood hears muffled voices, followed by the sound of fists thudding into flesh.

“Hey, you. Why are you still loitering?” The desk sergeant peers down crossly from his perch. “Get out of here, before I arrest you.”

Mahmood shudders as he hurries out of the police station. The Mumbai police are know for their brutality, and their prisoners occasionally turn up as bloated corpses, buried among the garbage dumps of Santa Cruz.

Well, the Don is a criminal, he’s chosen to live this life. But still.

Leaving the police station, Mahmood knows that he has just one more contact left: Rohini Khandelkar, his sweetheart from accounting college. She is married now, to an official, someone high up in Customs and Immigration. Rohini used to be very fond of him, surely she’ll help. But it is going to be tricky.

* * *

Mahmood rings Rohini’s doorbell—her apartment is on the sixteenth floor—and waits, remembering with a pang her thin girl’s body and sweet, round face. When the door opens it takes Mahmood a second to recognize the thick, matronly figure wearing a white salwaar-kameez. But Rohini gasps in surprise, and her smile is the same, wide and delighted.

“Mahmood Momjee, after all these years. Just like that. What are you doing in Mumbai?”

Oho, the old magic still works. Mahmood explains that he is passing through on business, but does not mention Zeenie or her passport. Rohini nods vigorously and ushers him in.

“What a wonderful home you have.” Mahmood takes in the marble-floored living room, the antique bronze statue of Nataraj, the fake leather couches.

“Yes, it’s nice. Suraj is doing well at work, God be thanked. It’s so nice to see you. Sit, sit.”

Mahmood sinks down into a couch. “Well, I just wanted to stop by for a few minutes and ask you if-”

“You look wonderful, Mahmood. So youthful. Just as I remember.” Rohini stares at him with unmasked joy.

“Why thank you. I can’t believe you look so…grown up.”

“I’ve become fat. The weight won’t come off, no matter what I do.”

“No, no, you look wonderful. Wonderful.” Mahmood has the pleasure of watching her blush.

“But Mahmood, you must be starving, it is lunchtime.”

“Oh, no, no, I don’t have time for food, I wanted to ask you-”

“Well let me at least make you a cup of tea.”

Before he can protest, she has hurried down a corridor and is out of sight. Mahmood slumps deeper into the leather couch and looks out: a sliver of Arabian Ocean is visible between the massed high-rise buildings.

He tries to remember why he had broken up with Rohini, why he had thought she was not good enough for him. After his accounting degree, he could have proposed to her; they could have had a small wedding, started out in a tiny apartment in Bandra. He could have taken a government job, made money—not large bribes, just small ones—and by now he could have bought a flat just like this one. If he had gone down that path, he now would have a wife who cared for him, whose face brightened when she saw him…

Rohini returns with a silver teapot on a tray and a plate piled high with deep-fried savory samosas. They are delicious, with a flaky casing and soft potato filling.

Watching him eat, Rohini smiles again. “Home made, you know. But this is nothing. If I had known you were coming, I would have made some proper food-”

A loud wail comes from an adjoining room. Mahmood startles, and the plate jumps in his hands.

“Aare, sorry Mahmood, one second, I’ll be right back.”

Disappearing down the hall, Rohini returns a minute later, carrying a small bundle in her arms. “Here, just hold him for a second. I have to heat up some milk.”

Stunned, Mahmood is left holding a tiny baby, surprisingly warm and heavy. Rohini has a child? He rocks the child back and forth, and it looks up at him. It looks nothing like Rohini, it resembles a wizened old man, with sparse hair and small, curious black eyes.

She returns with a bottle of formula and feeds the baby who sucks greedily, making smacking noises.

They talk some more, about Dubai and Mahmood’s important job at the Dubai Bank, but Rohini is only half-listening, distracted by the baby, who gurgles and spits milk. Mahmood cannot get over the baby, and it becomes a wedge between them, a reminder of Rohini’s absent husband.

There is no way now that he can tug at her heartstrings, and ask her for help. Soon Mahmood says that he really must be going, that he has a business meeting across town, and stands up, brushing samosa crumbs from his lap. Rohini grows more and more confused, but she does not dare to broach the past and ask him the real purpose of his visit. Ten minutes later, Mahmood finds himself descending in the elevator, the samosa he had eaten sitting like a brick in his stomach.

He has no choice now but to try his last approach.

* * *

It is three-fifteen, and very hot outside, the sky empty of birds. Mahmood stands sweating on the third-floor verandah of the Passport Department. An endless line of people snakes along it, holding numbered tickets, a lethargic bureaucrat at the far end calling out for the lucky few.

Mahmood barges to the front of the line, past the glaring eyes and the whispered threats.

“Do you have a number?” The bureaucrat’s eyes are dull with fatigue.

Mahmood thrusts Zeenat’s warped passport forward. “No. But I am willing to pay the expediting fee.”

The man seems to wake up. “Expediting fee? I’ll see what I can do. Wait here.”

Mahmood stands in the verandah, feeling the still heat. Tall palm trees rise from the courtyard below, their tattered heads silhouetted against the glittering sky.

The bureaucrat comes back and gestures Mahmood into a dark back room. Another man, trim in a starched white shirt, sits under a whirling ceiling fan.

“So, you are willing to pay the expediting fee? This is a very complicated situation. Damaged passport. Will take at least two months.”

“I need it by this evening. We’re travelling tonight.”

“Let me see what I can do.”

The man disappears into a rear office. A few minutes later, the door opens a crack, and a hand gestures Mahmood in.

This office is chillingly air-conditioned, and the official behind the mahogany desk wears a blazer with polished brass buttons. The inner sanctum: Mahmood feels a rush of success.

“Mr. Momjee, so good to see you,” the official says, as though they are old friends. “Do you have the required payment? That will be fifty thousand rupees. Mind you, I cannot give you a receipt.”

“That’s not a problem.” Mahmood triumphantly hands over the money. He has stopped at a bank along the way and drawn on his dwindling credit line.

The man bows, and leaves through a side door. Left alone, Mahmood looks out of the large window. There is an expansive view of the courtyard below, its scraggly flowerbeds and palm trees giving way to a small metal gate and the street beyond.

The man in the blazer returns, his smile slightly strained.

“So, Mr. Momjee, do you have the clearance from the Tax Office?”

“No, I’m afraid not. Can you take care of it?”

The man purses his lips and stands at the window, looking down absently into the empty courtyard. “I’m afraid if you do not have the requisite documentation, we will need to double the fee.”

“A hundred thousand rupees? That’s insane!”

The official holds out his arms, showing his empty palms, as if to say, It is out of my control.

Just then Mahmood sees a man emerge into the courtyard below. His grey suit jacket is slung over his shoulder, and he stops to rub at his wrists before getting into a white Ambassador that speeds away. Mahmood cannot believe his eyes.

“That’s Don Hajji Mustafa,” he blurts out.

The official’s face grows pale. “What? You… you know the Don?”

“We came in early this morning. On the same plane from Dubai.”

The official looks as though he is going to faint. “You are part of the Dubai group? Oh my God.”

Mahmood is about to protest, is about to say that the man is completely wrong, but then he doesn’t. He simply nods his head.

“Mr. Momjee, please forgive me. Everything was done in such a rush. I thought there was only one new passport, not two. But of course, if the Don needs this lady to travel with him, there is no problem, no problem at all…”

Motioning Mahmood to wait, the official scuttles out of the room. Mahmood sits on a rattan chair and holds his breath.

In twenty minutes, he has a new passport for Zeenat. The money he’d handed over is tucked neatly into its pages.

The official in the blazer accompanies Mahmood down to the street. As they part, he whispers urgently in Mahmood’s ear.

“Please, sir, do not mention this mistake to the Don. Please forgive me.”

Mahmood nods and hurriedly hails a taxi. He shrinks down in his seat, expecting to be found out at any moment. But as the taxi turns onto Marine Drive he sits up straight, fear replaced by giddy triumph. He chuckles to himself as he fingers the new passport with its crisp blue cover.

Ha. What is old Joojebhoy going to say when he sees this!

* * *

It is almost five by the time Mahmood reaches the Joojebhoy mansion. He finds Zeenat and her father in the gloomy living room, drinking tea under a darkened oil painting of a clipper ship. They sit close together on a couch that has ornately carved feet, and when Mahmood enters the room, both of them stare blankly at him, as though they cannot remember exactly who he is.

Mahmood strides towards them, brandishing the passport. “I have managed it,” he says. “Take a look at this.”

Zeenat looks startled. Old Joojebhoy reaches out and takes the passport between thumb and forefinger, as though handling a dead fish.

Mahmood stands before them, feeling the silence grow. “Zeenie, we have to pack and head for the airport. There’s a lot of traffic and the lines for these Thailand flights…”

Joojebhoy coughs. “Sit down, please, Mahmood. I need to talk to you. Zeenat has been telling me all afternoon about how unhappy she is. I think it’s better if she doesn’t go with you.”

“Not go with me? Why?”

“Mahmood, as you know, Zeenat has been unhappy in Dubai for quite some time…”

“Yes! That’s why we’re going to Thailand! It’ll cheer her up!”

“Mahmood.” The old man says his name gently. “What I’m trying to say is that… I hurried Zeenat into this marriage, and she is very unhappy.”

“But sir, if she doesn’t like Dubai, we can move somewhere else. I can find a job in America. Texas! California-”

“Just listen, Mahmood. You don’t understand the situation. A few years ago, my daughter was involved with an older man, not of our community…someone I did not approve of. So I arranged her marriage to you, thinking that it would all work out. But it has been a year, and Zeenat is not happy. I cannot bear to see my daughter like this. It is best—while there are no children—to call it off. The divorce will be quick, painless. I will pay for all the legal expenses.”

Mahmood’s voice is a whisper. “This is not fair. You approached me with the wedding proposal… it’s not my fault she’s in love with someone else-”

Ali Joojebhoy draws himself up to his full height. “Enough. No more talk. There is nothing more to say. My car will take you to the airport.”

Mahmood’s head is spinning as he turns to Zeenat.

“Zeenie, please. This is madness. I’ve been patient with you, but enough is enough.”

Zeenat gets up from the couch. “Husband? You call yourself a husband? You are a mouse, not a man. We’ve been married for one year, and we have not consummated our marriage. What kind of man are you?”

“I was trying to be considerate, I thought that-”

“Mouse! You are afraid of me! Afraid of a woman!”

“Please!” Ali Joojebhoy’s face has turned red, and he looks wildly from his daughter to Mahmood. “Enough. Mahmood, I know this is sudden, but I will compensate you, I will make sure that you have-”

“To hell with you people. I don’t want your bloody money!”

As Mahmood stalks out of the room, he catches a glimpse of Zeenat’s crisp new passport lying on the coffee table.

* * *

There is no way that Mahmood is going to Thailand now. The smiling woman at the ticket counter says that he is in luck; the very plane he had taken this morning is returning to Dubai in an hour, and there is one free seat.

Mahmood goes through the security check, passing through the metal detector. He stands in one of four parallel lines moving slowly towards the immigration booths. The thump-thump-thump of the officials’ stamps fills the air.

He feels like he is in a dark, badly lit dream. He thinks about returning to the empty apartment in Dubai, Zeenat’s hair tangled in the sink, her shelves full of cosmetics, her DVD collection of Hindi films strewn about. What is he going to do now? He looks around desperately, as though trying to wake up.

And that is when he sees the elderly man in the line next to him: grey-haired, wearing a badly cut suit jacket and the heavy, black-framed glasses of the socialist years. Not an unusual type, a retired army office perhaps, or a minor bureaucrat.

The old man is sweating, and seems anxious, his hands trembling faintly as he looks at his passport. It is the crisp blue passport that makes Mahmood look again: a brand new one, of the type he had procured for Zeenat just hours ago.

The old man’s face is lined, his hair convincingly thinned out, but when he looks up, his eyes, sharp and intelligent, are a dead giveaway.

Don Hajji Mustafa and Mahmood stare at each other.

Both lines shuffle forward another step. They are seconds away from the immigration booths.

The Don stares steadily at Mahmood, his eyes resigned. It’s your decision, his eyes seem to say. I know that I am trapped. Do what you have to do.

The Don’s face is impassive, but Mahmood sees the beads of sweat trickling down from his hairline, smells the high, hormonal stink of fear.

Mahmood is exhausted, so tired that he can hardly stand. The day has been endless, he and the Don like pilgrims on an arduous journey, bruised and battered at every turn. Mahmood feels a wave of hatred for those who run things, who are fickle and careless with human lives.

Without thinking, Mahmood lifts his chin slightly upwards, and signals to the Don, Go ahead. I won’t stop you.

An official shouts, “Next!” and when the Don steps up to the immigration booth, he is suddenly an old man again, smiling the weak, watery smile of the aged.

The Don is stamped through quickly, the bored official barely glancing at the grey-haired old man, but Mahmood’s passport is examined closely, and questions are asked about his daylong stay in India. Mahmood provides a long, rambling explanation, and the official nods slowly, fingering the passport, before reluctantly placing an exit stamp on the same page as that morning’s entry.

By the time Mahmood emerges into the departure area, the Don is far ahead, halfway up a long escalator, heading towards flights that leave for Zurich, Lisbon and Moscow.

Mahmood stands at the bottom of the escalator, watching the figure of Don Hajji Mustafa grow smaller and smaller. He knows that the Don will now vanish like a ghost, never to be seen again, and he feels an inexplicable sense of loss.

Just then the Don reaches the top of the escalator. He turns and waves at Mahmood, a small, furtive flap of his hand. He mouths the words, Thank you.

Mahmood waves back, a cavalier swoop, as if to say, No big deal, my pleasure, anytime.

Even after the Don is gone, Mahmood stands stock still by the escalator, feeling a sudden, wild elation. The great Don Hajji Mustafa, who has people killed with the flick of a hand, who is the mastermind behind a global network, has appealed to him, Mahmood Momjee, for mercy. And he has been merciful.

He becomes aware that a disembodied voice is calling the Dubai flight. He walks to his gate, hands thrust deep into his pockets, head held high, shoulders back. It is the walk of a man who has seen the worst that life has to offer, and is no longer afraid of it.

Copyright © 2014 by A.X. Ahmad.

A. X. Ahmad was raised in India, educated at Vassar College and M.I.T., and worked for many years as an international architect. He splits his time between Washington, D.C. and Brooklyn, New York. He is the author of The Caretaker and the upcoming novel in the Rajit Singh series, The Last Taxi Ride, available June, 2014.

Excellent and very exciting site. Love to watch. Keep Rocking.