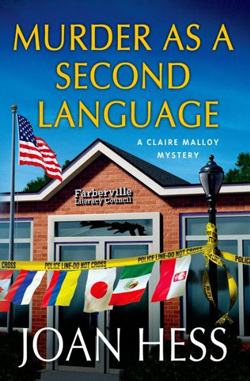

Claire Malloy—now a married woman of leisure—tries her hand at volunteering, but instead lands her right in the middle of another murder investigation

Longtime bookseller and single mother Claire Malloy has recently married her long term beau and moved out of her less than opulent apartment into a sprawling, newly remodeled house. Her daughter, Caron, is making plans for college. All of which leaves Claire with something she hasn't had in quite a while: spare time.

When her attempts to learn French cooking start getting “mixed” reviews, she agrees to help Caron and her best friend Inez in fluffing up their college applications by volunteering as an ESL tutor with the Farberville Literacy Council. But her modest effort to give back quickly becomes a nightmare when she’s railroaded onto the Board of Directors of the troubled nonprofit. Vandalism, accusations of embezzlement, epic budget problems, and a cacophony of heavily-accented English speakers are just the tip of the iceberg. Just as she decides that it might be best to extricate herself, Claire gets a frantic call from her husband, Deputy Chief Peter Rosen. One of the students, an older Russian woman named Ludmilla, famed for her unpleasantness, has been murdered in the offices of the Farberville Literary Council. For the first time ever, Peter actually asks Claire for her help.

Chapter 1

“Why’s your shirt covered in blood?” Caron asked as she sat down at the kitchen island and held up her cell phone to capture the moment.

“It’s mostly tomato sauce,” I said, peering at the recipe. There were twenty-two ingredients, and I was facing number sixteen: “easy aioli.” Apparently, it was too easy to suggest directions. I did not have Julia Child on speed dial. Number seventeen in the recipe was one cup of dry white wine. An excellent idea. I poured myself a cup and leaned against the counter, temporarily stymied but not yet defeated.

“Mostly?”

I waggled my index finger, which sported an adhesive strip. “I’m working on my knife skills. Cooking is not for sissies.”

My darling daughter wrinkled her nose. “It smells fishy in here. What on earth are you making?”

“Bouillabaisse. It’s a classic French fish stew. I intend to serve it tonight with”—I glanced at the cookbook—“crusty bread and a salad with homemade vinaigrette. For dessert, Riesling-poached pears.”

“Are we eating at midnight?”

I refused to look back at the horrendous mess that encompassed all the counters, the sink filled with bowls and utensils, the vegetable debris, open jars and bottles, and a splatter of tomato sauce, sweat, and tears. “I’m making progress,” I said loftily.

“Whatever.” She took a few more photos, then put down her cell. “You will be relieved to know that I may be able to go to college in a year, despite your lack of guidance. Otherwise, I’m doomed to survive on an annual income of less than twenty-five thousand. I won’t be able to go to the dentist, so all my teeth will fall out. No matter how badly I’m bleeding, I’ll have to tie a dirty rag around the wound and limp into work. My last manicure will be for graduation. Do you know how expensive fingernail polish is—even at discount stores?”

“I have no idea.” I went into the library and looked up “aioli” in a dictionary. “Garlic, egg yolk, lemon juice, olive oil,” I chanted as I returned to the kitchen and opened the refrigerator. Once I’d found eggs and lemons, I set them on the counter. “What specific lack of maternal guidance has imperiled your future education?”

“Community service—and I don’t mean the kind that some judge orders you to do. It has to be voluntary. You didn’t tell me that you have to show the college admissions boards that you’re committed to helping the less fortunate.”

“I applied to college in the Mesozoic era. I did so by filling out a form and submitting my transcript and ACT scores.” I paused to replay what she’d said. “Shall I assume you’re planning to fill that gap in your résumé? Did you volunteer at the homeless shelter or a soup kitchen? I can’t quite see you adopting a mile of highway and picking up litter in an orange vest.”

“Inez found this really cool place where we can volunteer to teach English as a second language to foreigners. It’s like four hours a week, and we arrange our own schedules. I figure that if we’re there from eleven to noon, we’ll have plenty of time to go to the lake and the mall.” Having rescued herself from a lifetime of cosmetology or auto mechanics, she moved on to a more crucial topic. “Can I have a pool party this Saturday afternoon? I want everybody to see our new house. I may even invite Rhonda Maguire and her band of clueless cheerleaders.”

“Our new house” was also known as my perfect house—a hundred-and-fifty-year-old Victorian gem, spacious yet cozy, with bits of gingerbread trim, hardwood floors that gleamed with sunshine, and twenty-first century indulgences. It was located at the far edge of Farberville, with a stream, a meadow dotted with wildflowers, and an apple orchard. There had been a few problems with the resident Hollow Valley family members involving malfeasance and murder, but I’d solved the case for the Farberville Police Department (and vacated the valley of the majority of its occupants). We’d moved in two weeks earlier. Now Peter, my divinely handsome husband who had been blessed with molasses-colored eyes and an aristocratic nose, had his own tie rack, his own wine cellar, and his own chaise longue on the terrace overlooking the pool. I’d claimed the library as my haven and spent a lot of time playing on the rolling ladder that allowed access to the highest shelves of books. I’d also arranged the contents of the walk-in closets, added artwork, located most of the light switches, and mastered the washing machine and the dryer. I’d barely seen my beloved bookstore, the Book Depot, since Peter hired a grad student to be the clerk. My presence was tolerated as long as I approved orders and invoices and signed checks. Lingering was not encouraged.

After a few days of reading poetry in the meadow, I felt the need to do something of importance. It was too early to make cider, and the idea of knitting made me queasy. Thus I had decided to master the art of French cooking. My boeuf bourguignon had been a success, as had the coq au vin; the terrine de filets de sole had been less so. My soufflé au chocolat had sunk. My petites crêpes aux deux fromages had been met with derision. C’est la vie.

“Yes, you may have a party,” I said as I attempted to separate an egg. “You handle the food—unless you want to serve tapenade noire and mousse de saumon.”

“How do you say ‘yuck’ in French?” Caron was too busy texting to wait for a response. “Do you care how many people I invite?”

I picked up another egg. “I suppose not, as long as you clean up afterward. I don’t see what’s so easy about aioli. Is there a utensil to crush the garlic? What’s wrong with garlic powder?”

“Oh, no!” she shrieked so loudly that my hand clutched the egg with excessive force. “I can’t believe this! I’ve already sent thirty e-vites. Everybody’s going to think I’m an idiot!”

I held my hand under the tap and let the gloppy mess dribble down the drain. “What’s wrong? Did Rhonda decline?”

“I got a text from Inez. We have to attend a training session at the Literacy Council on Saturday from ten in the morning until six. Eight hours of training to point at a picture and say, ‘Apple.’ It’s not like I’m going to explain the difference between the pluperfect and the imperfect. I don’t care, so why should they?”

“You can always be an aromatherapist.”

Caron gave me a contemptuous look over her cell phone. “You are so Not Funny.”

* * *

During the week, I attempted to conquer, with varying results, gratin de coquilles St.-Jacques, quiche Lorraine, and vichyssoise. My second soufflé went into the garbage disposal. Peter was so impressed by my relentless enthusiasm that he insisted on taking me out to dinner on Saturday. As we lingered over bifteck et pommes de terre (aka steaks and baked potatoes), he suggested that I might want to spend more time at the Book Depot, learn to play bridge, take a class at the college, or volunteer for a worthy cause. It was very dear of him to worry that I was expending too much time on housewife duties and would enjoy a respite. I gazed into his eyes and assured him that I was having a lovely time in the kitchen, although cooking and cleaning up could be wearisome. My eyes almost welled with tears as he spoke of the wealth of knowledge and experience I could share with the community, were I to sacrifice my nascent culinary goal.

I was thinking about our conversation the next day when Caron and Inez slunk in and collapsed on the sofa. Caron was fuming. Inez, her best friend, looked pale and distressed, and she was blinking rapidly behind the thick lenses of her glasses. I wiped my damp hands on a dish towel and joined them. “Problems at the Literacy Council yesterday?” I asked.

“Yeah,” Caron muttered. “The training session was interminable. The teacher basically read aloud from the manual while we followed along, like we were illiterate. We broke for pizza and then listened to her drone on for another four hours. After that, the executive director, some pompous guy named Gregory Whistler, came in and thanked us for volunteering. I was so thrilled that I almost woke up.”

“Then it got worse,” Inez said. “The program director, who’s Japanese and looks like she’s a teenager, told us that because of the shortage of volunteers in the summer we would each get four students—and meet with them twice a week for an hour.”

“For a total of Eight Hours.” Caron’s sigh evolved into an agonized moan. “We have to call them and find a time that’s mutually convenient. It could be six in the morning or four in the afternoon. We may never make it to the lake.”

I noticed that her lower lip was trembling. It was oddly comforting to realize that she was still susceptible to postpubescent angst at the très sophisticated age of seventeen. Caron and Inez had provided me with much amusement in recent years, along with more than a few gray hairs and headaches. Their antics had been inventive, to put it mildly, and always under the guise of righteous indignation. Or so they claimed, anyway. In the last month alone, they’d figured out a way to bypass a security system to get inside a residence. They’d abetted a runaway, hacked into a computer, and perfected the art of lying by omission. There may have been a genetic predisposition for that last one.

“Do you know who your students will be?” I asked.

Inez consulted a piece of paper. “We have their names and telephone numbers. We’re supposed to call them and schedule our sessions. I have a woman from Colombia, a woman from Egypt, and a man and woman from Mexico. I wish I’d taken Spanish instead of Latin.”

“And I,” Caron said, rolling her eyes, “have to tutor an old lady from Poland, a Chinese man, an Iranian woman, and a woman from Russia. How am I supposed to call them on the phone? They don’t speak English. Like I speak Polish, Chinese, Russian, and whatever they speak in Iran. This is a nightmare, and I think we ought to just quit now. I say we set up a lemonade stand and donate the proceeds to some charity.”

I looked at her. “That’ll impress the admissions boards at Bryn Mawr and Vanderbilt. Of course, you can always stay here and attend Farber College.”

She looked right back at me. “Yes, and I can live here the entire four years. Imagine the size of the pool parties when I meet all the freshmen. They can come out here to do their laundry and graze on bouillabaisse. You’ll be like a sorority and fraternity housemother. Won’t that be great?”

I went into the kitchen and leaned against the counter. I do not sweat, but there may have been the faintest perspiration glinting on my flawless brow. I’d created some lovely fantasies to explore after I recovered from the empty nest syndrome—which would be measured in hours, if not minutes. In the foreseeable future, scissors and tape would be in their designated drawer, my clothes would remain in my closet unless I was washing or wearing them, my makeup would lie serenely on the bathroom counter, and I could cease putting aside cash for bail money. I’d resigned myself to one more year—not five more years.

“All right, girls,” I said as I returned to the living room, “here’s my best offer. I will volunteer at the Literacy Council and take one student from each of you. You can decide which ones after you’ve worked out your schedules.”

Caron pondered this. “That means you only have to be there for four hours a week, while we have to be there for—” She stopped as Inez elbowed her in the ribs. “Ow, why’d you do that?”

“I think that’s a fine idea,” Inez said to me. “You have to do the training, though, and I don’t know how often it’s offered.”

I shrugged. “I have a graduate degree in English, and I was a substitute teacher at the high school. My grammar is impeccable, and my vocabulary is extensive. I’m likely to be better qualified than this teacher you had yesterday. This will not be a problem. Trust me.”

* * *

The adolescent Japanese girl purported to be the program director gave me a dimply smile. Her deep brown eyes twinkled as she said, “I am so sorry, Ms. Marroy, but the next training session will not be held until the third week in August. I hope to see you then. Now if you will be so kind to excuse me, I must return some phone calls.”

“If you want me to read a manual and discuss the material, I will do so, although it’s a waste of time for both of us.” I kept my voice modulated and free of frustration, although I was damned if I was going to twinkle at her. “I speak English. Your students want to learn to speak English. I fail to see the need for eight hours of training to grasp the concept.”

“It’s our policy.”

This was the third round of the same dialogue. Keiko Sakamoto, as her nameplate claimed, had feinted and dodged my well-presented arguments with “our policy.” I felt as if I were at the White House, trying to persuade the secretary of state to abandon the prevailing foreign policy. My chances in either situation fell between wretched and nil.

Keiko picked up the telephone receiver and with yet another twinkle said, “We always need volunteers for our fund-raisers. Please take this brochure with information about our program. Have a nice day, Ms. Marroy.”

I left her office with as much dignity as I could rally. The Farberville Literacy Council occupied a redbrick building in the vicinity of the college campus and had been designed well. The central area had clusters of cubicles equipped with computers, and a lounging area with chairs, tables, and freestanding bookshelves. On one side of the front door was a reception desk, unoccupied. On the other, the interior of Keiko’s office was visible behind a large plate-glass window. Rooms with closed doors lined the periphery. The passageways had black metal file cabinets under piles of boxes, books, and unfiled files. Everything was well lit and clean. As I hesitated, a classroom door opened and a dozen students emerged, talking to each other in several different languages. I recognized Spanish, German, and Arabic. Three young Asian women stared at me and giggled.

A tall, lean, fortyish woman shooed them out of the doorway, then hesitated when she spotted me. Her white blouse and khaki trousers would have suited her perfectly on safari, although Farberville had a dearth of exotic animals. I suspected she was trying to determine my native tongue as she walked across the main room. I was interested to find out how she would address me, so it was a letdown when she merely said, “May I help you?”

“My daughter and her friend are new tutors. They’re still trying to get in touch with their students. I was hoping that I could help out, but the next training session isn’t until the end of the summer.”

“You must be Caron’s mother. I’m Leslie Barnes, and I was the trainer on Saturday. It was a very, very long day for all of us.”

I had no trouble interpreting her look, but I wasn’t about to apologize. “The girls are excited about meeting their students, but leery of calling them on the phone because of the language barrier.”

“All of their students speak some English, as I told them. However, if they want to come here this afternoon, Keiko can help them make the calls and set up their schedules. I have another class in a few minutes. Nice to meet you, Ms. Malloy.” She went into a corner office and closed the door. I hoped her residual scars from the training session had not driven her to drink in the middle of the morning.

Two people emerged from an office beyond the reception desk. The man wore a dark suit, a red tie, and an annoyed expression. His hairline was beginning to recede, and his features seemed small on his tanned face. The woman had short blond hair, blue eyes, and deft makeup. She was wearing a tailored skirt and jacket and high heels, and she carried a briefcase. “Gregory,” she said as though speaking to a wayward child, “we’re still waiting for the receipts from your trip to D.C. two months ago. Are you going to claim your dog ate them? If so, you’d better have that dog at the next meeting.”

“They’re in my office somewhere,” he said. “Why don’t you ask Rick where they are? He’s been coming by after work to paw through the files. It’s a friggin’ miracle I can find my desk, much less the manila envelope with the receipts. You’ve got the credit card statement. I don’t see why you want a bunch of bits of paper.”

“Willie wants them, not me,” she said.

The man now identified as Gregory took her elbow and tried to steer her toward the front door. “You can’t have a meeting until you have enough board members present to make a quorum. That won’t be until August, will it? I’ll find the receipts before then—okay?” There was a hint of mockery in his voice.

The woman stopped and pulled herself free. “I suppose so. I need to have a word with Keiko before I leave.” She swept past me and into the office, muttering under her breath.

Gregory glanced at me before he returned to what I presumed was his office. I stood there for a moment, feeling as inconsequential as I did at the Book Depot. It might be the time for the third stab at a soufflé, I finally decided and headed for the door. Purportedly, it was the charm.

Before I could get into my car, the blond woman came outside and said, “Claire Malloy?” When I nodded, she held out her hand and said, “I’m delighted to meet you. I’ve read all about your involvement with the local police. Tell me, what’s it like to confront a murderer?”

“Unpleasant,” I replied. “And you are…?”

“Sonya Emerson. I’m on the board of the FLC—the Farberville Literacy Council. In my spare time, I work for Sell-Mart in the corporate office in the Human Resources Department. What’s more fun than a sixty-hour workweek?”

I wondered if Mattel had released MBA Barbie in the last few years. “It’s nice to meet you, Sonya. I came by to apply to be a tutor. It appears that I’ll have to wait for the next training session.” I opened my car door, but the subtlety escaped her.

“Keiko mentioned it. She’d love to make an exception in your case, but our executive director is adamant about sticking to our policy. We have to be certain that our tutors are committed. Some of them sign up, but then lose interest and abandon their students.” She frowned faintly and then brightened. “We’d love to have you volunteer in some other capacity. You’re so well-known and respected in Farberville. Having you involved in the FLC would enhance our reputation in the community, as well as in the state organization. You’re so intelligent and articulate.”

I enjoy flattery, but she was shoveling it on. “If you have a bake sale, let me know and I’ll whip up a batch of profiteroles au chocolat.” I waved as I got in my car and drove away at a speed appropriate for someone who was well-known, respected, intelligent, and articulate. If I ever needed a letter of recommendation, I’d call Sonya.

In the meantime, I was all dressed up with nowhere to volunteer. I parked in the Book Depot lot and went inside. The clerk, Jacob, gazed morosely at me from his perch behind the counter. “Good morning, Ms. Malloy. A shipment came in Friday, paperbacks for the freshman lit classes. They sent fifty copies of Omoo instead of Typee. I’ve already sent them back. Everything else was as ordered. Shall we have a sale for the remaining stock of beach books? Perhaps twenty percent off or three for the price of two?” His lugubrious voice reminded me of a funeral director displaying pastel coffins to the mourners.

“Whatever you think, Jacob.” I went into my office, which was disturbingly neat and sanitized. Even the cockroaches had lost interest. I thumbed through a pile of invoices, but nothing required my scrutiny. I toyed with the idea of stopping by the grocery store to pick up the ingredients for profiteroles au chocolat (after I found a recipe online), but I envisioned the mess I’d make and therefore be obliged to clean up. Volunteering at the public library was not an option; everything was computerized except me. I pulled out the telephone directory and found a list of organizations under the heading “Social Services.” Safety Net, the battered women’s shelter, declined my offer and suggested that I send a check. The Red Cross suggested that I take a class in first aid. The thrift stores suggested that I send gently used clothes and a check. Residential facilities for children and at-risk teenagers declined my offers—and, yes, suggested that I send a check.

It seemed as if my only option was to operate a charitable trust fund. I would have spare time to perfect magret de canard and galette des rois. Admitting failure to Peter would be painful. To distract myself, I called Caron and left a message on her voice mail, telling her what Leslie Barnes had said about making the calls. Which, I have to admit, sounded daunting even to Ms. Marroy.

Having devised no clever way in which to make a meaningful contribution to the community, I drove home and read a book by the pool.

* * *

Peter came home early and invited me for a swim. Since Caron wasn’t around, we indulged in some adult hanky-panky in the shallow end. After we were more modestly attired and armed with wine in the chaise longues, I told Peter about my dismal excursion into volunteerism. He commiserated, although I detected an undertone of amusement. I gave him a cool look and said, “I think I’ll talk to the police chief about setting up a victims advocacy program at the department. Someone needs to listen to them and steer them to the proper agencies. We can have lunch together. Is there a vacant office next to yours?”

“Not one in the entire building,” he said in a strangled voice.

I used my napkin to blot wine off his chin. “Maybe we can share yours. All I need is a tiny little desk, a computer, and a separate telephone line. I promise I won’t eavesdrop when you’re interviewing suspects. By the way, we’re having leftover quiche for dinner. Tomorrow I’m going to try to make avocat et oeufs à la mousse de crabe. That’s avocados and eggs with crab mousse. Sounds yummy, doesn’t it?”

Peter poured himself another glass of wine.

* * *

Caron and Inez arrived as we were finishing dinner. “We already ate,” Caron said as she went into the kitchen and returned with two cans of soda and a bag of corn chips. Inez nodded and sat down at the table.

“Did you talk to your students?” I asked them.

“Sort of,” Caron said through a mouthful of chips. “We went to the Literacy Council and let Keiko help. It was weird. She understood everybody—or pretended she did, anyway. Ludmila, who’s this ninety-year-old obese woman from Poland, about five feet tall, with squinty little eyes and a voice like a leaf blower, came in the office. Guess what? She happens to be my student. Lucky me.”

“She was kind of hard to understand,” added Inez. “Maybe because she was so upset about something. Keiko took her to the break room for tea. I met my two students from Mexico, Graciela and Aladino. They both speak some English.”

“As opposed to my students,” Caron cut in deftly. “Besides Ludmila, I got to meet Jiang, who’s from China and in his twenties. He talks really fast. I smiled and nodded, but I didn’t have the faintest idea what he was saying. For all I know, he was telling me where he buried the bodies or what he did with the extraterrestrials in his attic. The Russian woman’s English is pretty good. Anyway, we both have our teaching schedules. C’mon, Inez, let’s go to the pizza place in the mall.”

“I thought you’d already eaten,” I said.

Inez lowered her eyes, but my daughter had no reservations about mendacity. “We did, Mother. Joel and some of his chess club friends are celebrating their victory at a tournament in Oklahoma. Inez has a crush on this guy who turns red when you look at him.”

“Rory’s shy,” Inez protested. “Why do you always stare at him, anyway? He thinks that you’re going to scream at him.”

“That’s absurd. I am merely waiting for him to say something coherent, which may take years.”

Peter produced a twenty-dollar bill. “Have a good time.”

After they scurried away, he insisted on cleaning up the kitchen. I sat on a stool at the island, admiring his dexterous way with plates and silverware. We were idly speculating about Inez’s potential boyfriend when the phone rang. Since Peter’s hands were soapy, I answered it.

“Is this Claire Malloy?”

“Yes,” I admitted.

“I don’t believe we’ve met, but I have encountered Deputy Chief Rosen several times,” the woman continued. “My name is Wilhelmina Constantine. I’m a member of the Farberville Literacy Council board of directors, and I was told that you might be interested in volunteering for our organization. We’re delighted.”

“I was told that I have to wait for the next training session before I can be a tutor.”

“To be a tutor, yes. However, I’d like you to consider becoming a member of the board. You’re well-known in the community and have a background in retail. Although the FLC is a nonprofit, we’re forced to run a business as well. Raising funds, making payroll, dealing with vendors, all those petty nuisances. Your experience will be invaluable.”

“I doubt that,” I said. “Today was the first time I’ve set foot in the building. After I’ve been trained and have tutored for a few months, I’ll think about the board. You may not want me. Thank you for asking, Ms. Constantine.”

“I wish you’d reconsider, Ms. Malloy. If this wasn’t an emergency, I wouldn’t be asking. I’m afraid it is, and we’re desperate.”

I made a face at Peter, who was watching me. “An emergency?”

She remained silent for a moment, then said, “I really can’t discuss it on the telephone. We have an informal board meeting tomorrow night at seven o’clock. Would you please at least attend?” Her voice began to quaver. “Otherwise, the FLC may not survive the summer. Our students will have no place to go.”

“I’ll attend the meeting,” I said, aware that I was capitulating to emotional blackmail, “but only as an observer.”

“Wonderful.” She hung up abruptly.

“Ms. Constantine?” Peter murmured. “As in Wilhelmina Constantine, better known as Willie?” I nodded. “She’s a federal judge. Tough lady.”

“Her name is familiar, but I’m not sure why.”

“She made a controversial ruling a few years ago, but at the time you were distracted by Azalea Twilight’s unseemly death.”

“I was distracted because I’d been accused of murder and was being stalked by a certain member of the police department.”

“You were never accused of murder,” Peter said.

“Well, I was most definitively stalked. No matter where I went, you were lurking in the bushes, spying on me.”

The certain member of the police department raised his eyebrows. “I was not lurking. You went to extremes to make yourself unavailable for interviews, and the few times I cornered you, you flounced away like Scarlett O’Hara.”

“Fiddle-dee-dee,” I said. “I have never flounced in my life.”

“And I’ve never lurked.”

I thought about it for a moment. “Deal.”

Chapter 2

Thursday evening I arrived at the Farberville Literacy Council building a few minutes before seven. Students were chattering as they came out to the parking lot. Keiko waved at me as she climbed into a turquoise VW. Two women wearing hijab headscarves drove out of the parking lot in a silver Jaguar, followed by a carload of boisterous Latino men. A dozen students walked toward the bus stop on the corner. Sonya swooped in on me as soon as I stepped inside and, babbling with delight about my limitless virtues, escorted me into a classroom with tables arranged in a U formation. In one corner was a counter with a coffeepot, a minirefrigerator, and a sink. A chalkboard in the front of the room was covered with words, phrases, and primitive drawings that might have been found in caves in northern Spain. Maybe some of the students were neo-Neanderthals (although I hadn’t seen any woolly mammoths tethered outside).

“You must be Claire Malloy,” said a sixtyish woman carrying a coffee mug in one hand and several papers in the other. “I’m Wilhelmina Constantine, and I do want to thank you for coming. Please call me Willie.” I’d expected someone tall and regal, as befitting her lofty position in the judiciary, but she was short, pear-shaped, and, well, a tad frumpy. She was wearing a pink blouse that was missing a button, and her skirt reminded me of a washboard. Her frizzy gray hair had not withstood outbursts from prosecutors and defense attorneys. Her eyes were close-set, and her nose was as sharp as a beak. Despite her smile, she had the look of an offended songbird.

“I don’t know how I can be of help,” I said, resisting the impulse to chirp.

“We’ll get to that in a minute. Sonya, introduce Ms. Malloy to the others so we can get started. I’ve been on the bench all day and haven’t had a martini, much less dinner.”

Sonya assessed the situation and gestured to a thirty-something-year-old man, who promptly stood up. He was attractive and expensively packaged, with broad shoulders, a clean jaw, and a friendly expression. His light brown hair was carefully tousled. I wondered if he might be MBA Ken. “Ms. Malloy, this is Rick Lester. He’s a recent addition to the board.” The lack of warmth in her voice caused me to scratch my theory.

Rick’s blue eyes met mine as if he were auditioning for the role of earnest young man of impeccable integrity. “I’m Claire,” I said.

“The fabled sleuth of Farberville,” he said with a bow. “I’m delighted to meet you, Claire.”

“Ah, thank you.”

“I’ve only lived in Farberville for a couple of months, but I’ve heard of your exploits.” He smiled at Sonya, but she turned her back to speak to Wilhelmina. “Are you working on a case now?”

“Not that I know of,” I replied. “Are you enjoying Farberville?”

Rick chuckled. “It’s quieter than Hong Kong. It’s hard to fall asleep without the incessant cacophony of horns blaring and neon lights flashing. Before that, I was in Manila, also a busy place. I worked for an international financial outfit. Now I’m only a small-town banker.”

“Why Farberville?”

“I know some people who used to live here, and they loved it. I’m still adjusting to the pace. My previous jobs came with a chauffeur and full-time help, so I haven’t owned a car since I was in college—or scrubbed a toilet. Now I’m learning how to drive myself around town. It seems to be a nice place to settle down.”

Sonya swooped in once again and said, “Let me continue the introductions.” We approached a middle-aged man wearing dark-framed glasses, slacks, and a beige cotton sweater. “This is Drake Whitbream, our vice president. He’s the dean of the business school at Farber College. Perhaps you’ve already met him.”

He held out his hand. “Ms. Malloy and I have met at a few functions. It’s so kind of you to join us.” He was a big man who’d probably been an athlete in decades past. Years in academia had softened him and added a sprinkling of gray hair.

He was somewhat familiar, I thought, trying to find his face in a memory. “Yes, at a reception at the Performing Arts Center. You and your wife…?”

“Becky,” he supplied promptly. “Aren’t you married to a police detective?”

“Something like that. Your son plays football at the high school. My daughter and her friend are big fans.”

His face tightened briefly. “Toby will be the starting quarterback this season. He’s determined to get a football scholarship at one of the big universities and then go pro. With his grades, an athletic scholarship is the only way he’ll get accepted.”

I shrugged for lack of a better response.

“Can we get started?” asked a woman who’d entered the room and was now seated at the head table. She spoke with such authority that everyone hastily found a chair. “Where’s Austin? Has anyone heard from him today? Sonya, call his cell.” She looked at me as if I were responsible for Austin’s absence. Her firmly curled hair and predominant chin made her face look round, but far from jolly. Saggy jowls gave her an air of perpetual dissatisfaction. None of her buttons would dare go missing. “Welcome, Ms. Malloy. I am Frances North, the president of the board. It is very kind of you to join us on such short notice.”

“Austin will be here in five,” Sonya reported as she put down her cell phone.

“I’ll bet he stopped at a liquor store,” Rick said, lacing his fingers behind his neck. He smiled at me. “Austin is our bad boy. Frances would love to kick him off the board, but she needs his vote.”

Frances was not amused. “Don’t be ridiculous. Austin has done an excellent job publicizing the Literacy Council’s programs and events. I certainly do not dictate his vote. Now let’s get started.” She shifted the papers and files in front of her for a moment. “Here is the situation, Ms. Malloy. Currently there are twelve members on the board. Due to illness and vacations, only six of us are active this summer. According to the bylaws, this does not constitute a quorum, which means we can take no action in regard to certain sensitive issues. However, we do not require a quorum to increase the size of the board. If you agree, we will vote to add your name to the board. With thirteen members, seven will make a quorum. All you’ll have to do is attend any meeting that requires your vote. You needn’t concern yourself with these issues.”

“I haven’t agreed to anything,” I said, “and I certainly won’t unless I know what I’m getting myself into. Why can’t this be resolved when the other board members are back?” I began to wish I’d sat closer to the door.

Frances shook her head. “It’s time-sensitive, and we cannot risk any leaks if the FLC is going to survive. That’s why we’re here—and why we need you. Where is Austin?”

“At your service,” a young man said as he entered the room, a bottle of wine in each hand. “Rick, will you get the cups out of the cabinet? Good evening, everyone. Willie, you’re looking especially fine. I hope this doesn’t mean you’ve been frolicking with your clerk.” He wore pale blue slacks with pink suspenders, a short-sleeved dress shirt, and a pink bow tie. His teeth were very white against his dark skin. A metrosexual nerd, I concluded, although I was aware that snap judgments were unreliable. Other people’s, anyway.

Willie sputtered while Austin opened both bottles of wine, but she eventually accepted a cup of white wine, as did Sonya and I. Drake declined. Frances North sat in silence, emanating disapproval until Rick and Austin sat down. I was relieved that I was not a member of their oenological conspiracy.

“Claire, this is Austin Rodgers.” Sonya said, tersely. He and I nodded at each other—tersely.

“Austin, I informed you at the last meeting that we would no longer have wine,” Frances said. “Keiko told me that some of the Muslim students were upset when they found empty bottles in the trash. Our primary concern is our students.”

He took a sip of wine. “So I’ll take the empty bottles home with me. If there’s to be no wine, then there’s to be no Austin. I didn’t get away from my office until six thirty, and I need a fix. Why do you have your pantyhose in a knot, Frances? Did the third graders march on your office, protesting cafeteria food?”

Frances stood up. “Shall we proceed? Do I hear a motion to nominate Ms. Malloy for membership in the Farberville Literacy Council board of directors, pursuant to article six, paragraph four of the bylaws?”

“Wait just a minute—” I began.

“I so move,” Sonya said quickly.

“Second,” Drake said even more quickly.

“All in favor please raise your hand.” Frances avoided looking at me as she glanced around the table. “The motion passes unanimously. Welcome to the board, Ms. Malloy. If you choose, you may resign at the first official meeting in September, but of course we’ll be delighted to keep you.”

I wondered if I was supposed to give an acceptance speech. “I’m honored,” I said without enthusiasm. They could elect me in a nanosecond, but I could always resign in half of one.

“Why wouldn’t you be honored?” Austin refilled my cup. “I propose a toast to Ms. Claire Malloy for her courage. Not everyone would willingly embroil herself in such a maelstrom.”

“Don’t exaggerate, Austin,” Willie said. “It’s more of a bother than anything else, and Claire needn’t worry about it.”

“Until she gets sued,” he said.

I found my voice. “Wait just a minute! I’m going to be sued? What’s this about?”

Drake stood up and closed the door. “She deserves to know, people.”

That was the first sensible thing anyone had said since my arrival. I placed my hands on the table and looked at Frances. “Well?”

“A small problem with our finances,” she said. “Rick?”

Rick cleared his throat. “I joined the board this spring. Although Willie is our treasurer, I looked into the grants, expenditures, and so forth. There are some subtle discrepancies that suggested further analysis. The FLC hasn’t had a full audit in five years, and the board budgets according to Gregory’s monthly reports.”

“He’s talking about embezzlement,” Austin said as he winked at me. “Bankers are incapable of using the word. It sticks in their throats like a whalebone.”

“We will not use that word,” Frances said. “The books are a mess, and the bank statements are confusing. Right now Willie, Keiko, Gregory, and I are authorized to write checks. Some of us are sloppy about noting the details of the expenditures. I received a notice earlier this week that we were in arrears with the electric company. I paid it from my personal account so they wouldn’t turn off the lights. Gregory swears that Keiko is responsible for the bills, but she said that he takes them into his office and loses them in the clutter. As for the credit card statements…”

“We might as well shred them,” Sonya said. “The real problem is that those of you who write checks reimburse yourselves without, as you said, noting the details of the expenditures. Gregory can’t keep the accounts organized without receipts.”

Willie did not look pleased with the discussion. “I bought office supplies because they were on sale. I did not have an FLC credit card or checkbook with me, and I wasn’t about to drive all the way over here. I felt entitled to reimburse myself. If you have a problem with that, you can reimburse me the seventy-nine dollars I spent.”

“Don’t push your luck,” Sonya replied. “Seventy-nine dollars is a drop in the bucket—or should I say, your budget?”

Surprised at Sonya’s flippancy, I waited for Willie to bash her with a concealed gavel, but she sat back and picked up her cup of wine. I decided to take my new position seriously. “Why not have an audit? That should identify the source of the discrepancies. Aren’t nonprofits obliged to have yearly audits?”

“Full audits cost thousands,” Drake said. “We don’t have enough cash in the account to pay for the audit and stay open this summer. Because of the economy, our grants are shrinking, and they have to be used for specified programs. A few of our benefactors have told us that we won’t be receiving anything from them.”

“Then a bake sale it is!” said Austin. “And the next weekend, a car wash. After that, we can rent out students for housecleaning and yard work.”

“Your suggestions will not be noted in the minutes,” Frances said coldly.

Rick waggled his fingers. “I could use a chauffeur and a houseboy.”

“While Willie,” Austin added, “definitely could use a lady’s maid to stitch on buttons. It’s a good thing that you cover yourself with a long black robe, Your Honor.”

“You’d better pray you never end up in my courtroom, young man.”

“Enough.” Frances thumped her fist on the table. “This meeting was called to elect Ms. Malloy to the board. Our official meeting is next Monday at five o’clock. Austin, you need to arrange to leave work early. Sonya, please have the minutes typed up. Do your best with a financial report, Willie. Let us hope that we can behave in a more decorous fashion. Meeting adjourned.”

She scooped up her papers and left the room. Sonya and Willie retreated to a corner to speak in hushed tones. Neither of them appeared amicable. Drake wished me a pleasant evening and left. I looked across the table at Austin. “Where do you work?”

“At a local TV station, in the advertising department. I produce some of those memorable messages from used car dealerships and carpet stores.”

Rick laughed. “Last night I caught the one with the flying sheep, and I must say it was brilliant, my friend.”

“I agree,” he said, handing Rick one of the wine bottles. “Where do you work, Ms. Malloy? I envision you as a medical examiner, or perhaps an insurance appraiser.” He squinted at me for a moment. “No, neither of those. Are you a covert agent for the CIA?”

His crack about the CIA startled me, since Peter did have some sort of relationship with the agency. He’d never explained, and I’d long since given up asking him. “I own a bookstore on Thurber Street called the Book Depot. My degree is in English literature, and the sight of blood makes me dizzy. I have also been described as ‘a loose cannon,’ rendering me useless as a covert anything.” I picked up my purse. “I’ll see you on Monday.”

Now the main room was lit only by a dim light over the receptionist’s desk. Although there was daylight outside, the scarcity of windows left the interior gloomy. The cubicles looked like dark stairways into the basement, if there was one. I made my way around them, mindful of the boxes piled on top of file cabinets that lined the wall. I may have been a bit nervous, but I could hear voices from the room behind me. If I’d been alone in the building, I would have been more than a bit nervous—but only because I was unfamiliar with the floor plan. I was pleased to arrive at the exit, and was scolding myself for being a ninny when the door opened abruptly.

I gulped at the towering figure, his face obscured by shadows. “Good evening,” I managed to say.

The figure moved into the light. He was, I realized, a teenager with floppy hair and a sprinkle of freckles who might live on the Jersey Shore. He wore tattered denim shorts and a T-shirt emblazoned with an advertisement for a brand of beer. His grin was lopsided and disarming. “Good evening. Who are you?”

“I’m here for the board meeting.”

“Shit, nobody told me or I would have waited.”

“Are you a tutor?”

“I’m the janitor, four nights a week. I clean the toilets and mop the floors and empty the trash—and I don’t even get paid. It sucks, lemme tell you. The students toss banana peels and half-eaten oranges in the wastebaskets. I found a moldy tangerine in a cabinet in the women’s restroom. I about barfed.”

“It must be a brutal job,” I said, more interested in getting past him to the parking lot. “I guess somebody has to do it.”

“Well, I’m that lucky somebody.”

“Perhaps you should quit.” I sidled to my right, hoping to dart around him. I’d listened to more than my fair share of whiny teenagers. Caron, precocious child that she is, stormed home from first grade to demand that I have her teacher fired for tyranny. By middle school, she was filing complaints in the principal’s office.

“Like I can quit? That’s a joke.”

“Toby,” Sonya said as she emerged from the maze, “enough of this. You’re wasting Claire’s time—and yours. Keiko told me that you haven’t vacuumed the classrooms this week. Make sure you do the offices, too.” She reached up to brush a lock of hair out of his eyes. “And no more pouting, okay?”

He flashed us a quick grin, then continued on his way. I gazed at Sonya until she finally said, “Drake’s son. He had, uh, a spot of trouble with the police and was sentenced to a hundred hours of community service. Drake arranged for him to work it off here instead of picking up trash along the highway. Toby’s a good kid, just clunky and rebellious like all teenagers these days.”

“I’m sure he is,” I said, then smiled and went out the front door. To my annoyance, she stayed on my heels like a nascent blister, asking me what I thought of the board of directors and “interpersonal dynamics.”

I opened my car door. “To be honest, I didn’t pay that much attention. I was too busy being manipulated. At the first hint that I’m somehow personally liable for this financial mess, I’ll nail my resignation to the door.”

“Don’t worry about it. I’m so glad you came, Claire.”

She may have said more, but she would have been talking to my taillights. When I was safely out of sight, I decided to stop for coffee before I went home. Peter was at yet another meeting in Little Rock, and Caron and Inez were off with their friends. I wondered if they knew that their idol was working off his community service at the Literacy Council. Quarterback, in the restroom, with the mop. I’d barely seen the girls in the last few days. They’d managed to schedule their students between eleven and two, which meant they could sleep late, grab breakfast on the way out the door, and drag home from the lake just in time for a shower before heading for the mall or a pizza place. I’d not heard complaints about their tutoring sessions—or much of anything else.

I parked at Mucha Mocha and went to the counter. The menu board was so complicated that I ordered unadulterated coffee, to the barista’s disdain, and then sat down on the back patio. I’d hedged the truth with Sonya; I’d been quite interested in the so-called interpersonal dynamics. Only out of curiosity, I assured myself. I’d already encountered more than enough murders for the summer, and embezzlement was entirely too mundane.

The patrons did not provide much entertainment. Most of the students were entranced with their laptops, their hands flickering over the keyboards like dragonflies over a pond. A few were engrossed by electronic readers and cell phones. They might glance up if a bomb exploded nearby, but I doubted I could gain their attention by standing on a table and ripping off my clothes. The coffee shops of my college days were loud and raucous places where philosophical arguments competed with poetry slams and subversion. This place resounded with clicks.

I glanced up when a voice said, “Do you mind if I join you?”

It took me a few seconds to recognize Gregory Whistler, the executive director of the Literacy Council. Flustered, I said, “Please do.”

He introduced himself, requiring me to do likewise, and then said, “I saw you the other day, and then at seven o’clock, going into the building. Keiko told me that you wanted to become one of our tutors. We’ll look forward to having you once you’ve gone through the training. I know it’s silly, but the state Literacy Council insists. Were you dropping off the application form?”

“No one has mentioned an application form,” I said. I knew precisely what information he was after, but I wasn’t in the mood to enlighten him. “My daughter is a tutor. Although it’s hardly urgent, I’ll ask her to pick up one for me. The next training session is at the end of the summer.”

“Yes, good point. I was leaving when you arrived. Did you want to speak to me about volunteering in another capacity? Next month we’re having a potluck picnic for the students, their families, and the tutors. We need all the help we can get. A lot of the students have large families, and they allow their kids to run wild. Last year we had an unfortunate incident involving alcohol, sushi, mustard, and couscous. No one was arrested, but I’m afraid that we might have a repeat this year.”

“I’ll have to check my calendar.” I was aware that I was being uncooperative, but I’m always in the mood to outwit the witless. I finished my coffee. “It’s been lovely chatting with you, Gregory. Perhaps I’ll see you at the FLC sometime in the future.”

“Please let me offer you another cup of coffee,” he said. Before I could decline, he added, “I’m aware of your reputation, Claire, and I’d be deeply appreciative if you’ll hear me out. Something’s going on at the Literacy Council, and I’m afraid.” He reached for my mug. “Ten minutes, okay?”

I nodded and sat down. Gregory took our cups inside for refills. If what I’d heard at the meeting implicated him in an embezzlement scheme, he had every right to be anxious. I could think of no reason why he might want to share this with me. He had come to the obvious conclusion that I’d attended the board meeting in some capacity, and surely he’d realized by now that I wasn’t going to pass along what had been said. If he was hoping to buy my allegiance with overpriced coffee, he was out of luck.

He eventually returned, bearing two cups, and resumed his seat. “Thank you, Claire. This has nothing to do with whatever took place at the board meeting.” He paused for a long moment. “This may sound paranoid. I’ve been the executive director for four years, and until recently, there have been no problems. I’ve pulled in a lot of grant money and donations, and done my best to see that the funds are allocated to the proper programs. Our immediate financial situation is grim, but I’m confident we can continue to operate on a reduced level until the economy improves. We’ve cut back on evening classes and close at one on Fridays.”

“That seems reasonable,” I said.

“I think so, but apparently I’ve stirred up resentment from an unknown person or persons. A couple of months ago I went into my office and found red splatters on my desk and the files I’d set out the previous evening.” He held up his palm. “No, not blood. It was paint, but meant to convey the message that it might be my blood the next time.”

“Are you sure? Were there painters in the building? One of them might have wandered into your office and made the mess. Or what about Toby’s cleaning supplies?” Not that I could truly believe either scenario, since cleaning solutions are rarely bright red.

Gregory shook his head. “It was a message, the first one. The second was a dead bird in my wastebasket. It didn’t open a window and fly inside.” He crossed his arms and stared at the tabletop, his forehead creased. When he finally picked up his cup, his hands were trembling. “Maybe I’m paranoid, but I’ll be damned if I can come up with a reasonable explanation. Last week my name plaque disappeared. Yesterday someone got into one of my desk drawers and made off with my flask and a box of antacids. That may be nothing more than petty theft by one of the students. I don’t know.”

Toby sprang to mind as the culprit. He might have taken the flask, but I couldn’t envision him pocketing the antacids. If he had a grudge against Gregory, he was capable of mischief. However, it seemed more likely that he was angry at his father for forcing him into menial labor.

“Have you told the board?” I asked.

“I asked Keiko about the paint, but she was mystified. I didn’t see any point in mentioning these nasty pranks to any of the board members. I’m in enough trouble with them without being perceived as a whiner.”

“Trouble over receipts? When I dropped by yesterday morning, I overheard the conversation between you and Sonya.”

He rolled his eyes. “That’s the reason, for the most part. I admit I can be disorganized when I’m up to my chin in paperwork, but I have saved all of my receipts in manila envelopes labeled accordingly. Either I misplaced them or they’ve vanished. It shouldn’t be Sonya’s problem, anyway. Willie is the treasurer.” He stirred his coffee with a wooden stick as he sighed. “Someone is out to get me.”

“Why?”

“I wish I knew, Claire. My position is hardly prestigious or lucrative. I suppose I could find a management position elsewhere, but I want to make a contribution to the community. With our assistance, our students are able to get better jobs, communicate with their children’s schools and doctors, and integrate into the culture.”

I noted that his eyes were moist. He was either very sincere or very talented. “That’s admirable, Gregory.” My reply was lame, so I tried to rally. “Your background is in management?”

“After I graduated, I worked for my father’s company, a medium-sized pharmaceutical manufacturer headquartered in Europe. Ten years ago Father retired to a tropical island to continue his campaign to hold the record for most marriages and divorces in one lifetime. His current wife is twelve years younger than I, and never met a mirror that didn’t love her. I can’t recall her name offhand.”

“How did you end up in Farberville?”

“My wife went to college here, and she loved it. She—well, she died two years ago. I’m still trying to deal with it. Rosie was such a wonderful person, generous, caring, and very sensitive. She taught math at a middle school, but she was looking forward to having a houseful of children. We agreed to wait for a few years so we could settle into the community. When I went through her things, I found a folder filled with magazine articles about decorating nurseries and making baby clothes.”

“I’m sorry for your loss,” I said.

“Thank you.”

We sat in silence for a few minutes. I finished my coffee and gathered up the torn sugar packets and stirrers. Gregory looked up, almost startled, when I said, “I need to go home now. I suggest you keep your office door locked when you’re not there. These pranks seem juvenile at best.”

“Yeah, I suppose so,” Gregory said as he stood up. “I shouldn’t have bothered you with my petty problems. Our students are adults, but they bring their children from time to time. I’ll take your advice and lock my door. If that offends anyone, he or she will have to get over it. Thanks for hearing me out, Claire. I don’t seem to have any friends these days. Rosie was the one who drew friends like a magnet. They tolerated me.” He tried to chuckle. “Not that I’m a total bore. I just don’t seem to have the energy to make an effort to get back out there and start dating.”

If he was hitting on me, he was miles away from making contact. I smiled and went back into the café. As I squirmed through the crowd, I saw Rick seated alone at a table in a corner. He looked away, but not before we’d made fleeting eye contact. I continued out to my car and fished in my purse for my keys, feeling a sudden urge to leave before any other members of the board popped up behind a bush—or slid into my backseat. While I drove home, I composed a letter of resignation to the board, replete with gratitude for the honor of being elected and expressing dismay that I’d suddenly remembered I had to wash my hair on Monday night. I had no desire to embroil myself in their skullduggery and angst and pettiness. I wondered if Meals on Wheels would allow me to deliver bouillabaisse to the elderly and disabled. I would be an adorable candy striper. It might not be too late to enroll in summer school and take a class in nineteenth-century poetry. I’d always wanted to take up pottery. Pottery and poetry could be my salvation.

Or there was always culinary school.

Copyright © 2013 by Joan Hess.

To learn more about, or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Joan Hess is the author of both the Claire Malloy and the Maggody mystery series. She is a winner of the American Mystery Award, a member of Sisters in Crime, and a former president of the American Crime Writers League. A long-time resident of Fayetteville, Arkansas, she now lives in Austin, Texas.