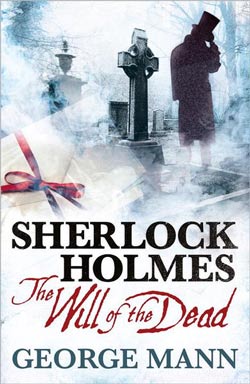

Enjoy this exclusive excerpt of the first two chapters of Sherlock Holmes: The Will of the Dead by George Mann, a brand-new adventure for the detective and Dr. John Watson (available November 5, 2013).

Enjoy this exclusive excerpt of the first two chapters of Sherlock Holmes: The Will of the Dead by George Mann, a brand-new adventure for the detective and Dr. John Watson (available November 5, 2013).

A young man named Peter Maugram appears at the front door of Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson’s Baker Street lodgings. Maugram’s uncle is dead and his will has disappeared, leaving the man afraid that he will be left penniless. Holmes agrees to take the case and he and Watson dig deep into the murky past of this complex family.

Chapter One

From the testimony of Mr. Oswald Maugham

I woke to the sound of shattering glass.

Startled, I sat up in bed, my heart thudding. It was dark – well past midnight – and my first thought was that someone had put out a window and was attempting to enter the house.

I blinked the sleep from my eyes, waiting for my vision to adjust to the stygian gloom. The house was silent, save for the distant ticking of the grandfather clock in the hallway below. I held my breath, listening nervously for any sounds of movement. Nothing.

The moment stretched.

My thoughts seemed sluggish – whether from being dragged so unceremoniously from sleep, or from the copious amount of claret I’d consumed during the evening’s festivities, I could not say. I closed my eyes, feeling the pull of unconsciousness. I told myself the sounds had been imagined. There was no need to get up, no need to trouble myself. A mere dream…

I was close to drifting off again when I heard movement on the landing – footsteps, accompanied by the low murmur of a mumbling voice. I sat up, knowing now that my earlier fears were not unfounded.

I am not, by nature, a brave soul, but I could not allow a potential intruder to go unchallenged. I slid from beneath my eiderdown, shocked by the sudden cold of the floorboards against the soles of my bare feet.

I crossed to the door, cautious and quiet. I paused for a moment, listening. There was more murmuring, coming from along the landing.

I turned the key in the lock and pushed the door open, cringing at the creak of the ancient hinges. I peered out. A shadowy figure stood at the top of the stairs, surrounded by a diffuse globe of lamp light.

It turned at the sound of my movement, and I realised, with a sigh of relief, that it was only Uncle Theobald.

“Oh, thank God,” he called, his voice wavering. “Is that you, Oswald? Lend me your arm, will you? I’m not sure what the devil’s come over me tonight.”

I pushed the door open and, pulling my dressing-gown around my shoulders and tying the sash about my waist, I emerged onto the cold landing. I saw Jemima, Uncle Theobald’s black and white cat, dancing around his feet. She mewed noisily as she rubbed against his shins.

“Yes, yes, Jemima. Just a moment longer. Oswald’s here to help.”

I crossed the hallway, the floorboards creaking. “Uncle?” I asked, concerned. “What are you doing out of bed at this hour?” He looked haggard, his eyes lost in shadow. “You look unwell. Here, let me help you.” I put a reassuring hand under his arm, supporting him.

Uncle Theobald was an elderly man, and his ailing health over recent months had been a cause of great concern for my cousins and I. Nevertheless, that night he seemed rather more out of sorts than usual. I took the lamp from him, holding it up so that I could see properly. His face looked pale and craggy, the myriad lines cast in stark relief. He narrowed his eyes at the sharpness of the light, and I lowered the lamp again.

“Thank you, my boy. Thank you. I’m feeling rather light headed. I spilled my drink… I…” he faltered, his shoulders sagging. He expelled a long, heartfelt sigh. “I’m old, Oswald. Old and feeble.” He sounded bitter, as if he were carrying a great burden, frustrated by his inability to carry out tasks that, only a few months earlier, had seemed like second nature.

“Uncle, those stairs are treacherous and you’re clearly in no condition to attempt them unaided. You really should know better,” I said, gently admonishing, but careful to avoid patronising him. “You could have called for Agnes. Or one of us.” I sighed. “Look, I’ll fetch you another glass of water myself.”

Uncle Theobald smiled sadly. “You always were a thoughtful child, Oswald,” he replied, patting my arm. “I’ve promised Jemima here some of that chicken, too. See to that, would you, while you’re downstairs?”

“Chicken?” I asked, rubbing my eyes. I was still half asleep and desperate to return to my bed, but I couldn’t allow Uncle Theobald to go running about the house in the dark.

“Quite so. The leftovers from the party. I had Agnes put some aside on a plate in the pantry.” He grinned. “Didn’t want Jemima to miss out, you see.”

I glanced down at the cat, which was still mewling around his feet. “He spoils you, Jemima,” I said with a chuckle. I stooped and ruffled the fur behind her ears. “I’ll see to it, Uncle.” I straightened up, taking his arm. “First, however, allow me to escort you back to your bed.”

“Very well,” he replied gratefully, allowing me to take some of his weight. We shuffled slowly across the landing to his chamber, where I ushered him towards his bed, careful to avoid any fragments of broken glass. The floorboards were damp where he’d dropped the tumbler, but the water had mostly drained away, leaving scattered shards of glass that shone when they caught the fleeting light.

Jemima had followed us, and jumped up onto the bed as Uncle Theobald pulled the heavy blankets over his legs, propping himself up on the pillows. She meowed loudly.

“I’m sorry, Jemima,” said Uncle Theobald, conspiratorially. “You heard him. I’m under orders. If you go with Oswald, though, he’ll fetch you that chicken I promised.”

I hesitated for a moment, as if stupidly waiting to see if the cat would acknowledge what Uncle Theobald had said and follow me, but it seemed she was set upon haunting the poor chap all night. She didn’t seem to want to leave his side, as if – and I realise this sounds ridiculous – she was exhibiting some sixth sense, some foresight of what was to come.

Of course, at the time I knew none of this, and put it down to the vagaries of the animal, who had always been Uncle Theobald’s pet and no one else’s, trailing around after him as he drifted from one empty room to the next, stirring up the dust and the memories in the old house. Sometimes, it was as if Uncle Theobald himself was a relic of the past, and Jemima his only reason for living.

“There. Now you make yourself comfortable and I’ll return momentarily with a drink,” I said.

I left the room and made for the stairs, holding on to the banister as I descended into the murky gloom of the hallway. It didn’t seem worth lighting the wall lamps, so I made do with the flickering oil lamp, traipsing across the cold marble floor and along the passageway to the kitchen. The inky darkness was eerie, the only sounds the swishing of my dressing-gown, the soft thud of my bare feet and the rattle of my breath as I hurried through the kitchen and into the pantry.

I found the plate of chicken and placed it on the floor in the kitchen beside Jemima’s water bowl. Then, leaving the lamp on the table, I filled a glass with water from the tap, and drained it. I then replenished it for Uncle Theobald. I collected the lamp and hurried back to the stairs, eager to return to my bed.

“I know, I know. I’m disappointed too, girl. Can’t even fetch myself a ruddy glass of water without causing a fuss.” Uncle Theobald was talking to Jemima when I knocked gently on his open door, and he looked up, beckoning me in. “Ah, thank you, Oswald. You’re a kind boy.”

“I haven’t been a boy for many years, Uncle,” I chided, grinning.

“No, no, of course not,” he replied with a chuckle.

“Right. Here you are,” I said, placing the glass on his bedside table. “We’ll have Agnes clear this mess away in the morning.” I indicated the remnants of the previous glass. “You get some rest, and be careful not to stand on any of this when you rise.”

Uncle Theobald sighed. He reached for the water and sipped at it slowly. “Very well.” He returned the glass to the bedside table and sunk back into his pillows, his eyes already fluttering closed. “Goodnight, Oswald.”

“Goodnight, Uncle. Sleep well,” I said, turning down the oil lamp. “And goodnight to you, too, Jemima.” I crept from the room and along the landing to my own chamber, where I hastened to bed, and soon after fell into a deep, restful sleep.

I woke to the sounds of someone stirring; a door opening and closing, water running, footsteps on the landing. It was still early – around six o’clock, I estimated, and I groaned wearily as I propped myself up on one elbow, blinking away the last vestiges of sleep.

I started at the thud of something landing upon my chest, and looked down to see Jemima staring up at me with plaintive eyes.

“Oh, hello, Jemima. What are you doing here? Is it morning already? I must have left the door ajar.” I stroked the fur on the top of her head, and she mewled happily. “Where’s Uncle Theobald, eh? Well, I suppose it’s almost time for breakfast. Did you polish off that chicken?” She looked at me curiously, tilting her head to one side. I sighed. “Look, you’ve got me doing it, now. Talking to a cat –” I stopped abruptly at the sound of a dreadful, ear-splitting shriek. It was perhaps the worst sound I have ever heard; the raw, terrified, primal scream of a woman.

“Agnes!” I called, throwing back the covers and sending Jemima sprawling on the bed. I ran out onto the landing. “Agnes?”

I could hear her whimpering in the hallway below, and I hurried to the top of the stairs. She was huddled at the bottom, her back to me, slowly rocking back and forth on her knees. I could see she was bent over something bulky, but it was obscured from view.

“Agnes? What’s wrong? Whatever’s happened?” I asked, with trepidation. I started down the stairs toward her. Behind me I could hear doors being flung open as the rest of the household, woken by the screaming maid, came rushing out to see what had occurred.

“Oh, Mr. Oswald, sir,” gasped Agnes, between sobs. “There’s been a terrible accident. Sir Theobald…” She drew a deep intake of breath, moving to one side so I could see. There, on the marble floor, lay the broken remains of my uncle. His head was resting at an unnatural angle and blood had trickled from his nose, forming a glossy pool beside him. One arm looked broken, and his eyes were open and staring. I felt a creeping sensation of dread in the pit of my stomach.

“Good God!” I cried, hurtling down the remaining steps to his side. “He must have fallen in the night!” I dropped to my knees, meaning to search for a pulse, but found I could not bring myself to touch him. He looked so pale, and I could see that he was no longer breathing. “Is he…?” I stammered, already knowing the answer.

“Yes, sir,” sobbed Agnes, unable to control her tears. “He’s… he’s…” she whimpered. “Sir Theobald is dead.”

Chapter Two

Of all the many adventures of Sherlock Holmes that I have chronicled these long years, the mystery surrounding the death of Sir Theobald Maugham still lingers in my mind as perhaps one of the most unsettling, and certainly one of the most affecting.

For many years I had thought not to set it down, in part due to the sensitivities of that fateful family, but as much – in truth – because I could not even begin to see how to record such a complex web of betrayal and deceit.

I hope that perhaps, with the benefit of time, I may finally be able to present it here, if not only to once again demonstrate the deductive cunning of my friend and associate, but also to set straight the record of what truly occurred.

It began on a grey evening in late October 1889. Domestic duties had kept me away from Baker Street for nearly two full months, and the long summer had given way to a fruitful, mellow autumn. The streets were wreathed in a low-lying mist that curled around the gas lamps and softened the harsh lines of the city. I’m not ashamed to admit that I was happy and enjoying married life, and my thoughts had been far from murder, blackmail, or any of the other forms of criminal activity that typically punctuated the time I spent with Holmes.

Holmes himself, on the other hand, unable to find a case that could hold his attention, had once again retreated into one of his insufferable black moods. He had taken to lounging about the apartment in his tatty, ancient dressing-gown, smoking his pipe incessantly and indulging in his deplorable chemical habit. In his drug-induced lethargy, he had abandoned all sense of cleanliness and propriety. The apartment was cluttered with abandoned teacups, heaped plates and a landslide of discarded newspapers. Mrs. Hudson had, for the last week, refused to enter his chambers, and it had been her hastily scrawled missive that had brought me to town, and to Baker Street, that very morning.

I had bustled into the apartment with the intention of admonishing Holmes for his lackadaisical behaviour. Although I had learned from experience that my chastisement was unlikely to stir him from his ennui, I felt obliged to make the attempt all the same, both for his sake, and for that of the long-suffering Mrs. Hudson.

He had his back to me when I entered the room, propped up in his armchair by the fire. His bare feet were resting up on a small table, and he was drawing his violin bow steadily back and forth across the strings of the instrument in an apparently random fashion, causing it to emit a violent, disharmonious screeching – rather, I considered, echoing my own present temperament.

“Holmes?” I said, full of bluster. “What the devil do you think you’re doing, man? Poor Mrs. Hudson is beside herself! Stop torturing that damn instrument for a moment, will you, and listen to an old friend.”

To my satisfaction, the screeching came to an abrupt halt.

“Ah, Watson!” replied Holmes, delighted. “Yes, I was rather expecting you,” he continued, in a more languorous manner.

This somewhat took the wind from my sails. “You were?” I said, a little indignantly.

“Naturally,” replied Holmes, with a dismissive wave of his hand. He lowered the violin and turned about in his chair to regard me. I could see he was wearing his crimson dressing-gown over a tatty black suit, both of them pitted and pockmarked with tobacco burns and chemical stains. His eyes were hooded and lost in shadow; he was evidently not in the best of ways.

“Then you knew of Mrs. Hudson’s letter?” I prompted, resignedly. The fight had already gone out of me. Now, I could think only of how I might assist my friend, to set him once again on the path from which he had strayed.

Holmes removed his feet from the table and set the violin down in their stead, fetching up his briar and tobacco slipper. He began filling the pipe, tamping the weed down into the bowl with his thumb. “Yes, yes, Watson. Mrs. Hudson is nothing if not predictable, and you, my good doctor, are a creature of simple habits. The letter was the least of the matter.” He struck a match, puffing on the end of the pipe as the flame took to the tobacco with a dry crackle.

“What on Earth are you talking about, Holmes?” said I, more than a little frustrated by his games. I wished to speak earnestly with him regarding his recent behaviour. I couldn’t help but feel he was engaging me in such trivialities in order to distract me from my goal. “Stop being so dashed opaque. I haven’t called in weeks. It could only be the letter that gave you warning.”

“It really is a trifling matter. Hardly worthy of discussion,” he said, with a shrug. Yet his tone of barely suppressed superiority belied his true intention – to toy with me.

“Holmes…” I said, testily.

He emitted a playful sigh. “Mrs. Watson is away visiting her mother in Sussex, is she not?”

“Yes…” I said, perplexed. “But… how did you know?”

Holmes laughed. “Really, Watson. It’s a simple deduction. Was it not the happy occasion of your mother-in-law’s birthday this last week? As it has been, on the twelfth of October, ever year for the last seventy-three?”

“Indeed it was…” I confirmed.

“And since I am aware that you and Mrs. Watson were away taking the air in Northumberland last week – you mentioned your impending constitutional in your last letter – it seems only logical that Mrs. Watson should wish to pay a visit to her mother directly upon your return.” Holmes took a long draw on his pipe, and allowed the smoke to curl from his nostrils as he regarded me. “Therefore,” he went on, “knowing you are a conscientious man, and that you would feel obliged to return forthwith to your patients, it is but a simple leap to assume you would take the decision not to join your wife on her call.”

“I cannot deny it,” I said, with a shrug.

“Left, then, to your own devices, I’d wager that yesterday evening you dined alone at your club, enjoying the company of your fellow medical men. Then, this morning, having discharged your duties – and before you had ever set eyes on Mrs. Hudson’s no doubt rather melodramatic missive – you had already decided to take the opportunity to pay a visit to your old lodgings, and to your friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes.” He finished his oratory with a flourish of his hand, before clamping his briar once more between his teeth and sinking back into the depths of his armchair, his gaze fixed upon the leaping flames in the grate.

I let out a heavy sigh. “As usual, Holmes, you explain it in such a logical fashion that it seems entirely obvious you should expect my call. But listen here, this destructive behaviour has got to stop. And as for that poison you insist on sinking into your veins… well, you know my feelings on the matter. I mean… look at this place. Look at you!” I gestured around me in dismay, aware that the timbre of my voice had altered as I’d spoken. It was not often that I found myself raising my voice to another – particularly a dear friend – yet I believe Holmes understood that my agitation stemmed purely from my concern for his health and wellbeing.

Holmes took his pipe from his mouth, cradling the bowl in the palm of his left hand, as if weighing it. He glanced up at me, his eyes shining with amusement. When he spoke his voice was level, his manner genial, as if my outburst had already been forgotten. “Calm yourself, dear Watson. You wouldn’t want to scare away our visitor. He’s evidently a rather indecisive example of his class.”

“Visitor, Holmes?” I mumbled, somewhat flustered.

“Indeed, Watson,” replied Holmes, with a flourish of his pipe. “Your timing is, once again, impeccable.”

“This is too much, Holmes. You mean to say you’re expecting a caller? Other than myself, I mean.” I found this somewhat hard to believe, given Holmes’s careless appearance and the state of his rooms. I couldn’t believe that even hewould countenance admitting a client to the premises with the place in such disarray.

“In a manner of speaking. It is my belief that within the next few minutes a man will call at the door, seeking my advice. A man with a grievous problem indeed. He is around six foot tall, in his thirties, and walks with a limp. He was never a soldier, suggesting his leg was afflicted by a childhood illness or accident. He is indecisive and of a nervous disposition. Two days ago, something terrible occurred that has today caused him to take a cab across town to seek my assistance.” Holmes had grown steadily more animated as he spoke, and was now sitting forward on the edge of his seat, clutching the bowl of his pipe between thumb and forefinger, eyeing me intently.

“You know this man?” said I, wondering at his game.

“Not at all, Watson,” said Holmes, with a chuckle. “We have not yet been introduced.”

“Then what gives you cause to anticipate his arrival?” I sighed, resigned now to indulging my friend in this little bout of sparring. At the very least, it had stirred him from his brooding. “Really, Holmes, your games can be quite infuriating.”

Holmes grinned wolfishly. “All in good time, Watson. All in good –” He stopped short at the sound of the doorbell clanging loudly from the street below. He sprang from his chair, suddenly animated. “Ah-ha! There he is.” He threw open his dressing-gown, thrusting his hands into his trouser pockets, his pipe clenched between his teeth. He paced back and forth before the fire for a moment. The doorbell rang again, and I heard the sound of Mrs Hudson’s hurried footsteps in the hallway below. A moment later the front door creaked open and the sound of a man’s voice – indistinct but most definitely hesitant – followed.

Holmes almost leapt over a pile of heaped leather-bound tomes, crossed the room towards me, and clapped his hand heartily upon my shoulder. “Now Watson,” he said, around the mouthpiece of his pipe, “be a good fellow and keep him busy for a moment, while I slip away and change.”

“I… I…” I stammered, but to no avail; he was already making a beeline for the bedroom door. “But Holmes!” I cried after him, despairingly. “The state of the place!”

My pleas fell on deaf ears, however, and the door slammed shut in abrupt response, leaving me standing amidst a scene that felt more akin to the battle-scarred ruins of Kabul than a British gentleman’s drawing room. I was surrounded by detritus, with the sound of our visitor’s footsteps already starting up the stairs.

“Well, I suppose I’ll just have to do it myself,” I muttered, in abject consternation. I glanced around in dismay. I have never been one to relish domestic chores, and the condition of Holmes’s quarters was decidedly shameful. Nevertheless, someone had to make the place presentable if Holmes was going to secure himself another case to investigate.

I set about hurriedly tidying away the filthy plates, stuffing them into the sideboard to hide them from view. I hoped that poor Mrs. Hudson would forgive me. I then gathered the abandoned newspapers into a large, irregular heap, and dumped them unceremoniously behind the sofa. There was very little I could do about the dust, but I crossed to the window and heaved it open, inviting a gust of cold – but clean – air into the room.

“There. That’ll have to do,” I muttered beneath my breath.

As if our visitor had read my thoughts, there was a polite rap at the sitting room door. I smoothed down the front of my jacket, took a deep breath and tried to dispel the harried feeling within me. I crossed to the door and opened it to see a man almost exactly matching the description Holmes had given. I smiled politely. “Oh, ah… come in,” I said, standing to one side and ushering him past me.

“Mr. Sherlock Holmes?” he asked nervously, extending his hand.

“I rather fear not,” I replied, with an apologetic shrug. “My name is Watson, Dr. John Watson, an associate of Mr. Holmes.”

The newcomer looked relieved, and turned back towards the stairs as if to depart. “Oh. Then perhaps I should call another time…?”

“Not at all,” I said, reassuringly. “Mr. Holmes will be along presently. Please, make yourself comfortable.”

To my relief, I heard footsteps behind me and turned to see Holmes, looking immaculate in a black suit and white shirt. He smiled brightly. “Good evening to you, Mr…?”

“Maugham,” replied the man, his shoulders dropping in what I took to be either relief or resignation. “Peter Maugham, sir.”

“Well, Mr. Maugham,” said Holmes. “Pray take a seat by the fire and warm yourself. Dr. Watson here will fetch you a drink for your nerves.”

“What?” I said, caught off guard. “Oh, yes. Quite.”

“Thank you, Mr. Holmes. I fear my nerves are, indeed, in tatters. I am close to the end of my endurance,” said Maugham, unbuttoning his overcoat and handing it to Holmes. He lowered himself into the seat I had previously occupied, and I sighed.

I crossed to the sideboard and fumbled for a clean glass, hoping I wouldn’t have to open the doors and reveal the terrible mess of dirty plates inside. Thankfully, there was a clean tumbler beside the decanter on a silver tray. I splashed out a measure of brandy and handed it to our visitor, before finding a perch amongst the detritus on the sofa. Holmes offered me an amused grin.

“Much obliged, Dr. Watson,” said Maugham. He sipped at the drink and nodded appreciatively.

“Now, Mr. Maugham, I see that something is clearly preying on your mind. I can assure you that Dr. Watson and I will hear your case without prejudice, and we ask only that you speak frankly and with as much accuracy as you can muster,” said Holmes, returning to his own chair opposite Maugham. “Leave out no detail, no matter how small or insignificant it may seem.”

“I shall do as you ask, Mr. Holmes, for I am indeed in need of your help,” replied Maugham, solemnly.

“Very good. Now, in your own time, would you care to elaborate on the reason for your call?” Holmes retrieved his pipe and settled back to listen.

Maugham cleared his throat. “Two days ago, Mr. Holmes, something terrible occurred to change my fortunes forever. I have lost everything. I am ruined.” He took another sip of brandy, and I noticed that his hand was trembling.

“Two days ago, indeed…” Holmes shot me another glance, with a raised eyebrow. “Pray continue, Mr. Maugham.”

“It was the occasion of my cousin’s birthday. The whole family, such as it is, was gathered at the home of my uncle, Sir Theobald Maugham. Sir Theobald is – was– a lonely man, with no children of his own. The Maughams, you see, have not been blessed with the sturdiest of constitutions. Sir Theobald’s siblings all died some time ago – my mother from a severe dose of influenza, an uncle from a wasting disease, and another to the war in Afghanistan.” Maugham looked pained as he listed the terrible fates that had befallen his relatives.

“An unfortunate family indeed,” I said.

“Quite so,” agreed Maugham. “As a consequence, Sir Theobald lived alone, rattling around in that big house of his. He doted on his niece, however – my cousin, Annabel – and on the occasion of her birthday he called us all together for a party.

“Well, we had a pleasant enough time of it, Annabel, Joseph, Oswald and I. Sir Theobald had become a rather eccentric figure in his dotage, but it pleased us all to see him in such high spirits. We retired late, each of us rather rosy cheeked and merry, and I saw Sir Theobald to his bed.” Maugham paused for a moment, as if collecting his thoughts.

“The next morning, however,” he went on, “I was woken by the sound of the maid’s screams. The same was true of my cousins, whom I encountered on the landing as I came barrelling out of my room. What we found was a sight none of us will ever forget. Agnes was at the bottom of the stairs, kneeling over the twisted body of my uncle, her face stricken with shock.”

Holmes was silent for a moment, respecting the gravity of the man’s words. “I’m very sorry for your loss, Mr. Maugham,” he said quietly. “Can you tell me, was it deemed that he had fallen?”

“Yes,” replied Maugham, gravely. “Yes, absolutely. The police doctor who came out to the house said that it was clear he’d fallen during the night. A terrible accident. We were always warning him about that staircase. It’s particularly treacherous.”

“You heard nothing to rouse you during the night?” asked Holmes.

Maugham shook his head. “No. But then I had been rather over zealous with the wine. We all had. When the police found the empty bottles from the party they were quick to conclude that it was likely Sir Theobald had tripped and fallen in a drunken stupor. The doctor confirmed as much when he examined the body. He said there was clear evidence that he’d stumbled and banged his head, breaking his neck on the way down. The smell of alcohol upon him served to support the theory.”

“But you doubt this conclusion?” I prompted. It was clear from Maugham’s tone that he did not entirely agree with the police doctor’s report.

“I don’t know what to think, Dr. Watson,” Maugham replied, unsure. “It’s just… given the events that followed… well, to be honest, I simply don’t know.”

“Please, continue then, Mr. Maugham,” said Holmes.

“As I’ve already explained, Mr. Holmes, my uncle lived alone, and my cousins and I were his only remaining relatives. He’d set it out in his will that the estate was to be divided equally amongst the four of us upon the occasion of his death.” He looked at both of us in turn. “I hope you’ll forgive me for discussing such vulgar matters, gentlemen, and I assure you that – at the time – thoughts of such matters were far from my mind. Nevertheless, my cousins and I have all grown used to living on my uncle’s generosity, and my sole income these last years has been an annual allowance from Sir Theobald.”

“We understand, Mr. Maugham,” I said, glancing at Holmes, who appeared to be observing Maugham intently.

“Thank you, Dr. Watson.” He sighed. “So it was that, later the same morning, once the police had removed my uncle’s body, the family solicitor, Mr. Tobias Edwards, came to the house to offer his condolences and to begin the necessary proceedings.”

“I assume that things proved not to be in order?” ventured Holmes.

“Quite correct, Mr. Holmes,” said Maugham, with a sad smile. “Mr. Edwards discovered that the will had been removed from its place in my uncle’s writing bureau. We turned the whole house upside down, but there was no sign of it.” He drained the rest of his brandy, placing the empty glass upon the table.

“Surely Mr. Edwards must maintain a copy at his offices?” I asked.

Maugham shook his head. “I fear not. Mr. Edwards explained that my uncle was quite specific about the matter – the only copy of the will, the original, was to be held at the house.” Maugham’s shoulders sagged. “Without it, I am ruined. I stand to lose everything.”

“Hmmm,” murmured Holmes, thoughtful. “I imagine your cousins must likewise have been frustrated by this unexpected development, Mr. Maugham?”

“Oh yes, indeed,” confirmed Maugham. “It is on behalf of us all that I sit before you today, Mr. Holmes, to beg for your assistance in locating the missing document.”

“It is this missing document that gives you cause to doubt the claims of the police regarding your uncle’s death?” asked Holmes.

“It is,” replied Maugham.

“You believe your uncle’s death and the missing will are connected, Mr. Maugham?” I queried, seeking clarification. “That the alleged thief is also a murderer?”

Maugham frowned. “No… Well…” he said, searching for words. His shoulders slumped in defeat. “Oh, perhaps, Dr. Watson. The trouble is, as much of a coincidence as it seems, I cannot see to what end the two things are connected. Only Joseph would gain from the loss of the will. Being the oldest surviving relative of Sir Theobald, he stands to inherit everything if my uncle dies intestate. Yet I cannot believe for a moment he was involved in my uncle’s death, even if he did prove to be responsible for the theft of the will. Even then, it is most unlikely, for he was the one who most strenuously supported my proposal that we come to Mr. Holmes for assistance in retrieving it.” He shook his head. “The entire matter is most distressing.”

“I quite understand, Mr. Maugham,” said Holmes. He stood, folding his arms behind his back and adopting a reflective pose.

I could see from the look on his face, and from the manner in which his brow furrowed in thought, that something about Peter Maugham and his story had captured my friend’s attention. I did not yet know what it was – why Holmes should deem this family’s affairs a worthy focus of his not inconsiderable intellect – but I knew at that moment that he would take the case on.

“Your story is certainly intriguing,” said Holmes, removing the pipe from his mouth and holding it by the polished mahogany bowl.

“Then you’ll take the case, Mr. Holmes?” replied Maugham, hopefully.

“Indeed I will.” Holmes gestured in my direction with his briar. “First thing tomorrow morning, Dr. Watson and I will make haste to the morgue to inspect Sir Theobald’s body, following which I should like to pay a visit to his house. Perhaps if you could arrange for us to be granted full and unequivocal access, Mr Maugham?”

“Of course,” replied Maugham. “I’ll send word to Mrs. Hawthorn, Sir Theobald’s housekeeper, to expect you.”

“Very good. There we shall no doubt begin to get to the root of your problem,” said Holmes.

The relief on Maugham’s face was palpable. “My thanks to you, Mr. Holmes,” he said, hurriedly. “It is a great comfort to my cousins and I to know you are investigating the matter on our behalf.” He stood, extending his hand to Holmes, who took it and shook it firmly.

“Well, until tomorrow, Mr. Maugham,” said Holmes.

“Yes, good evening to you, Mr. Holmes, Dr. Watson.”

I helped Maugham into his heavy woollen overcoat and showed him to the door. The change that had come over him since his arrival at Baker Street was quite remarkable. Where earlier I had taken him to be a nervous, uncertain man with a timid disposition, now he appeared to be confident and assured. I marvelled at the impact of Holmes’s brief statements, the affect he could have upon a person simply by agreeing to help. If nothing else, he had done this man a service.

I stopped Maugham by the arm, just as he was stepping across the threshold. “Mr. Maugham? One last thing, if you’ll humour a medical man. May I enquire how you injured your leg? Did you see military action in your youth?”

Maugham laughed, for the first time since his arrival. “Military action?” he echoed. “Why, not at all, Dr. Watson. I fear I was afflicted by polio as a child. Why do you ask?”

“Oh, curiosity, that is all,” I replied, avoiding eye contact with Holmes. “Good evening to you.”

“Good evening, Doctor. And thank you once again, Mr. Holmes.”

I closed the sitting room door behind him and returned to my seat on the sofa. A moment later we heard footsteps on the stairs, and then the front door banged shut as Maugham took his leave.

Holmes laughed, at first softly, and then more vigorously, throwing back his head as he revelled in his amusement. I felt myself flush. I knew it was at my expense. I allowed him his moment of triumph.

“Well, Holmes. You were right,” I admitted. “On every count. But how the devil did you know two days had elapsed since the incident in question?”

“Don’t look so startled, Watson,” he replied, playfully chiding. “You know my methods. The man had been pacing back and forth along Baker Street all afternoon. He’s indecisive, unsure of himself. I reasoned it had most likely taken a couple of days for him to pluck up the nerve to consult me.”

“A guess!” I exclaimed.

Holmes grinned.

“And what of the fact you knew he wasn’t a military man? I assume that had everything to do with the manner of his step?” I prompted.

“Very good, Watson!” said Holmes, surprised. “That and the fact a military man would never have been so indecisive.”

He was pacing back and forth before the hearth, animated and restless.

“I see you have that familiar gleam in your eye, Holmes. Something about this case has captured your attention,” I said. “Although I’m damned if I can see what it is.”

“Indeed,” replied Holmes. “Tell me, Watson – do you suspect that Mr. Peter Maugham is entirely what he seems?”

“I take it, then, that you do not?” I asked.

“Indeed I do not. Lies and falsehoods, Watson. Those agitated gestures were, I believe, the result of more than a simple nervous disposition. There’s more to that fellow than meets the eye. Mark my words: this is a dark business we’re embarking on.” His words were ominous, and I had no doubt they were the truth.

“So what now, Holmes?” I asked.

“Now, Watson?”

“Well, yes. I’d rather hoped Mrs. Hudson might be persuaded to set an extra place for dinner. If it’s not too much of an imposition, of course? With Mrs. Watson away… Well, I suppose I could always head back to the club if you plan on making a start on the case.”

Holmes laughed again, kindly. “My dear Watson! The corpse will keep until morning. I’m sure Mrs. Hudson will be only too happy to oblige her favourite culinary critic. And besides, I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

“Thank you, Holmes,” I said, with a satisfied sigh. I pulled myself up off the sofa. “I suppose in that case, then, I better ask Mrs. Hudson to see to those dirty dishes.”

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

George Mann is the author of The Affinity Bridge, The Osiris Ritual, and Ghosts of Manhattan, as well as numerous short stories, novellas, and an original Doctor Who audiobook. He has edited a number of anthologies including The Solaris Book of New Science Fiction, The Solaris Book of New Fantasy, and a retrospective collection of Sexton Blake stories, Sexton Blake, Detective. He lives near Grantham, UK, with his wife, son and daughter.