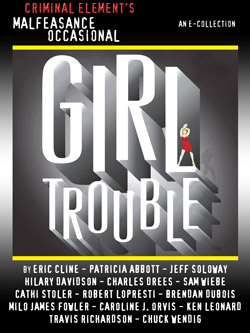

“Her Haunted House” by Brendan DuBois appears here in its entirety, and is joined by 13 other short crime stories in Criminal Element's inaugural e-collection, The Malfeasance Occasional's Girl Trouble issue (available for $3.99).

“Her Haunted House” by Brendan DuBois appears here in its entirety, and is joined by 13 other short crime stories in Criminal Element's inaugural e-collection, The Malfeasance Occasional's Girl Trouble issue (available for $3.99).

After enjoying this Halloween treat, try another complete story from this collection or learn more about the issue's contents and contributors.

I was early so I parked my rental car in front of the haunted house and tried to get some work done before my real estate agent showed up. This small neighborhood in Mullen, New Hampshire, was both foreign and familiar to me, like seeing your best friend from high school twenty years later: you see shadows and features that are familiar, overlaid by new life, new experiences. Here, I recognized two houses on either side of the haunted house—though they now bore different paint schemes—and I saw the narrow street to the left that I had played on many years ago. The pine and oak trees were larger, there was new shrubbery here and there, but the place was not foreign to me.

Yet the old large farmhouse and barn that had belonged to my grandparents down the narrow street was gone. In its place, and covering the pasturelands where grandpa had raised a few milk cows and some horses, were plain two-story homes in dull pastel colors, looking like they had been designed by an architect who learned his craft from a mail-order school.

The haunted house, though, pretty much looked like it did when I had last seen it, nearly forty years ago. It was an old Victorian, with peeling yellow paint, lots of impressive scrollwork and woodcarvings along the roof and beams, and a wide porch that was reached by a set of stone steps. The stone steps were uneven and crooked. I remembered them well. I still didn’t like them. On either end of the severely pitched roof were brick chimneys. A sign from a local realtor was plugged into the sloping lawn, at an angle, like it didn’t want to be there. I didn’t blame it, though it was odd, I know, to have traveled so far and so long to see this place up close.

From the passenger’s seat I took up the loose unbound galleys of my next novel, and on the third page in was the title of the book, The Forgotten Horror, and underneath it, my name, Holly Morant. Even after scores of published short stories and this, my tenth novel, I still find it strange to see my name listed as an author. It’s like either I’m fooling the world, or there’s another Holly Morant out there, pretending to me. I still haven’t figured out which is which.

I started going through the pages, black ink pen in hand, and after ten minutes of going over page one about a dozen times, I gave up and put the printed pages aside. I looked out again at the streets, now well-paved and with the nearby lawns and shrubbery well-groomed. I tried to look at the place through the mind of a nine-year-old, and remembered those long summer days and nights that seemed to drag on forever. Back then, of course, no cell phones, no MP3 players, no video games, no home computers, no texting, no chatting… hell, Grandma and Grandpa still made do with a black and white Zenith television set, and I was their remote control. It was always, “Holly, go to channel four now, will you?” and I’d scamper over and turn the knob. And sometimes I’d get to jiggle with the rabbit ears to pull in a better reception.

After breakfast, unless I wanted to help Grandma with the chores, I was tossed outside, where I’d play with the neighborhood kids until it was lunchtime, and then I was tossed out again. Back then, kids were trusted to be kids, and no one worried about kidnappers or criminals or strangers. Bad people, in the village of Mullen? Please. So it was just me and the local kids.

I’m sure at one time I remembered their last names, but now I just remember Greg and Tony and Sam, and Sam’s younger sister Penny…. we weren’t a gang or anything like that, just a group that hung out together. Greg was the oldest, eleven that summer when I was nine. And I guess he was the leader, always setting the plan for the day, but it wasn’t organized. It was just loose, lots of fun, and filled with days of play and adventure. No soccer league, or Little League, or field hockey, or day camp, or anything like that. Just running in the fields, looking in the local sandpit for fossils, collecting tadpoles in the shallow water of nearby streams, playing kickball or building a tree fort, or biking a mile to the local Dairy Queen, and… kid stuff. That’s all. At nighttime, we’d watch the stars, play hide and go seek, try to capture fireflies, or play flashlight tag.

I remembered. And I wished I had brought along some water, for now I was terribly thirsty.

I looked over at the haunted house. Sometimes, we’d sneak up on the haunted house, and torment the old man who lived there, who claimed he was a warlock and put spells on naughty children.

A honk of a horn startled me. I looked up at my rearview mirror.

Behind me a white Subaru had pulled up, and a woman with a too-wide smile was waving at me. I got out of the car and went further back in time.

• • •

I remembered the road in front of Grandpa and Grandma’s being dirt that had been sprayed down with a mix of oil and asphalt, meaning it got sticky during the days of July and August. It was always hot, it seemed, and I had a bedroom upstairs that was small and just stifling. Oh yes, the days before air conditioning, you know, though I had a whirring fan to keep me company at night, the fan moving back and forth, not doing much more than just stir the air around some. But if I was deprived, I sure as hell didn’t know it. All I knew that it was so much fun to spend the summer with my grandparents, far away from the Boston suburb where I was growing up.

Of course, I learned there were dangerous things out here as well. Snakes whispering their way through the tall grass, fisher cats at night that would howl and screech, and make you curl up in your bed in a little ball, hoping they wouldn’t tear through the front porch door screen. Ghosts, of course, and flying saucers with aliens ready to grab you. The cows were usually dumb and slow moving, but the previous summer, Greg had gotten too close to one and his left foot got stepped on, broke a few bones. And one day Grandpa came from one of the far pastures, cursing loudly, holding his left arm up, blood streaming down his wrist, after getting his hand sliced trying to cut a new fence post.

But nothing was as scary as the haunted house up by the T-shaped intersection and the warlock that lived there. His name was Henry Lee Atkins, and all summer long, he wore baggy green chino trousers or khaki shorts and sleeveless white T-shirts stained on the front. He smoked cigarettes all the time, and had white bushy eyebrows and little patches of hair that grew out of his ears. He never smiled, not once that I remembered, and another thing I remembered is that he liked to mow his lawn all the time, at least once or twice a week. After mowing it, he’d spend hours watering it. And God, did he hate having us running over his lawn, which we did a lot, because he owned a good chunk of pine forest at the rear that was a great place to explore.

We’d race by his house sometimes, while he was sitting on the porch, and Henry Lee would call out, “You kids slow down ‘fore you break your necks!” Greg, the bravest of us, of course, would yell back, “You stay away from us, you warlock!”

Another thing about Henry Lee was that he was missing his right foot. He had a prosthetic leg that he never bothered to cover with a sneaker or sock, and a couple of times, when he was hauling out trash to the side of the road—no sidewalks in this small town—he would pause and point at his leg and say, “That’s what I got for fighting the slant-eyes back in Korea. I was in the First Marine Division, nearly froze to death, and lost my foot at the Frozen Chosin. You’d think I’d’ve gotten a medal or something but no, the Marines and the government screwed me over good…”

One time I told Grandma and Grandpa about that story. It was late at night and we were watching Laugh-In on the Zenith, and Grandpa—working on his third Narragansett beer of the night—snorted and said, “That’s a hell of a story, and that’s all it is, a story. Lance Jenkins, down at the American Legion, he told me what really happened… old Henry Lee was in Korea but he lost his foot when he went on leave to Tokyo and met up with a couple of whores. He wouldn’t pay them and their pimp got payment by going after Henry Lee with a sword… sliced his foot… and Henry Lee was too stupid to get it looked at by a doc or a corpsman, so it got infected and they had to cut it off…”

Grandma, knitting, looked up and said quietly, “Roger.”

Grandpa took another swallow of his beer. “Damn it, Millie, that’s the truth. You know it. Don’t be bothering Henry Lee none, okay? Something about him… just ain’t right.”

Oh, I remember.

• • •

The real estate agent tumbled out of her Subaru, eager to be alive, very eager to see me, and very, very eager to seal the deal. I got out as well, my oversized black leather purse hanging from one arm. This was the first time I had met her face to face—our previous dealings having been done over the phone and e-mail—and after giving my outstretched hand a severe shaking, she said, “Clara Woodson, Holly, and I’m so glad to meet you.”

“Thanks for coming to see me here,” I said, getting my hand back and giving her a smile in return that was about eighty watts less than hers in intensity. She was plump, about ten years younger than me, her brown hair styled nicely with highlights. Above her black slacks, she wore an ugly yellow jacket, which bore an oversize name tag that had her name and the name of her real estate firm. I have many things to be thankful for, I know, and one is that at my age, I don’t have to wear a nametag.

Clasped to her chest by her thick hands was a leather binder, and she said, “Before we start, Holly… I have to say, what a thrill it is to have you up here. Now, I can’t say that I’ve read any of your books, but my daughter has, and I’m hoping you don’t mind autographing your latest for her when we’re done.”

“That’d be fine,” I said, waiting for the next inevitable question, and I was certainly not disappointed, for Clara said, “Your books… I know they’re bestsellers and all, but they’re really scary, aren’t they. With blood and horror and monsters and all that.” She giggled self-consciously. “I mean, you look so… chic. So nice. Hard to believe a pretty woman like you writes such dark tales.”

From inside my purse I took out a lighter and a pack of Marlboro’s. “Like we say in my world, you can’t judge a book by its cover.”

We went up the flagstone path to the steps, and Clara started talking about the house and its history and when it was built. I just lit a cigarette, took a deep, satisfying drag, and then dropped the cigarette down on the stone and squished it out, like the foul bug it was.

That brought another giggle from my real estate agent. “Didn’t taste right?”

“Tasted fine,” I said. “But I’m trying to quit, by cutting back.”

Clara said, “Oh, I hear that’s so tough.”

“Oh, no,” I said. “Quitting’s easy. I must have done it about a hundred times. Look, before we go into the house, I want to take a quick walk around the yard, all right?”

“Whatever you say, Holly,” she replied. “You’re the client.”

I walked up the slight slope of the lawn, to the right of the house, where the stone foundation was revealed, and something in my chest went thump-lump as I saw the two small and narrow windows built in the foundation. They were covered with wire mesh, and as I looked at the windows, thinking of what they kept in and what they kept out, I reached in my purse for another cigarette.

• • •

One cool dusk, I was out on the pasture to the rear of Grandpa’s house. Four Morgan horses were still at play at the far pasture, and the milk cows had been brought back to the barn. Grandpa didn’t feel like milking them anymore, so a young boy about a half-mile away came every morning and afternoon to milk them, and three times a week, the local dairy spun by to pick up the milk.

On this night, Greg and me and Tony and Sam and Penny were just racing around, playing tag, pushing and shoving, and Greg stopped and said, “Let’s go see what the warlock is up to.”

I remember laughing, saying, “He ain’t no real warlock.”

Tony and Sam both piped up, “Oh, yes he is, he really is, he’s a man witch,” and Penny rubbed a fist against her mouth and said plainly, “I don’t wanna go to the warlock’s house.”

Funny, I don’t remember much what the kids looked like. Greg was tall with blond hair, and Tony and Sam were shorter, more dark-skinned, and Penny had red hair and plenty of freckles. Penny’s hair was always in a braid, and the boys wore standard flat-top crew cuts. We all wore the summer uniform of T-shirts and shorts, or if it was cool, T-shirts and jeans.

So even though I was a bit scared—maybe Henry Lee really was a warlock—I said, “Okay, let’s go see what the warlock’s doing.”

We ran up the pasture and out to the road—about every twenty minutes or so, a car or truck would come by, so we really could play in the road without being worried—and went up to Henry Lee’s house. There were a couple of small lights on upstairs, but the cellar was lit up so that it looked like little searchlights were coming out of the basement windows. Greg led the way, and we scampered up the lawn and to the right, where Greg flattened himself down on his belly. We all did the same, except for Penny, who was standing back on the road, not daring to join us crazy older kids.

Greg moved on the grass, digging in his elbows—he claimed he had learned that from his oldest brother, before he was shipped off to Vietnam—and I went to his side, doing the same. My heart was racing along and the grass felt cool against my legs, but I also remember being excited that we were doing something scary.

It was hard to see inside the mesh screen. The lights inside were bright and I saw wooden shelves, and beams, and piping, and that was about it. I whispered to Greg, “So what do you think he’s doing down there?” and Sam answered for his friend, saying, “Potions and spells. That’s what I think. Potions and spells.”

Then all of the lights in the cellar suddenly went off, and I almost ran away, and then I really, really wanted to run away, when a deep, ghostly voice called up from the dark cellar, “Who dares come to my home uninvited?”

Greg called back, “You know who we are… what are you doing down there anyway?”

A cackling laugh came out that made me whimper—though later, as a teenager, I heard the laugh again and knew Henry Lee was doing a lousy imitation of Bela Lugosi—and he said, “My spells, my magic, to do terrible things to snoopy kids.”

I wanted to leave and even Sam and Tony were slowly sliding back on the grass, but Greg bravely—or stupidly—called out, “We don’t believe you, old man! You ain’t no warlock!”

“Come closer,” he murmured near the basement window, “and I’ll show you what kind of warlock I am!”

I don’t know if Greg was being stupid again, or was trying to show off to us younger kids, but he crawled up and said, “Here I am, old man!”

One more cackle, a voice: “Here’s magic acid to burn your face!” and something liquid sprayed out, and Greg grabbed at his face, screamed, and we all got up and ran out of there, yelling and shouting, Greg still screaming, both hands on his face, young and smart Penny leading the way back to Grandpa’s farm.

• • •

I stubbed out the cigarette again after two more puffs, and then put my lighter back into my large purse. The yard looked pretty good, all things considering, especially since Henry Lee Atkins had been dead for a number of years. Way I learned it, he got older and frailer with each passing year, and then a wound opened up in his amputated leg, and then he had to move into the state veteran’s hospital, where he lingered for a while before dying. Then the house and property was tied up in probate for another number of years, as various second cousins and other relatives fought over who got to have what, since Henry Lee didn’t have a will.

I stopped underneath an old clothesline stand, built like a wooden crucifix, with droopy clotheslines hanging low, and it was like my real estate agent knew what I was thinking about, when she said, “If I can ask, Holly, why are you so interested in this house, anyway? I mean, well, I know about you and your success… I wouldn’t think you’d be interested in having a residence here, so far away from everything.”

Success. A polite way of saying that for some reason, the sun, planets, stars and distant galaxies aligned themselves such that my first novel became an unexpected bestseller, and all of my subsequent books hit the New York Times list, and that because of my book sales, my foreign sales, audio rights, and the HBO mini-series in production, I could buy the entire town of Mullen and have enough money to maintain my homes in western Massachusetts, Idaho, and the British Virgin Islands without breaking a sweat.

I said, “I have a lot of memories, growing up here… and I was too late to buy my grandparents’ place, so I thought I’d do the next best thing, and buy this property instead.”

She nodded. “I see what you mean. Good memories and all that.”

I turned so she couldn’t see my face. When in God’s name did I say the memories were good ones?

• • •

By the time we got halfway to Grandpa and Grandma’s house that night, Greg had stopped on the bumpy road and made all of us stop running as well, and he said, “Shut up, you sissies. It was water. That’s all. The old bastard just splashed me with some water.”

I was breathing so hard I thought my chest would seize right up, and Penny was sniffling and Sam and Tony giggled, like they knew all along that it was just water that got sprayed on Greg, and Greg made us promise never to tell anyone what had just happened, and that’s what we did.

But I remember other things, too, bits and pieces that didn’t make sense at the time, but were important enough that the nine-year-old me would file it away, to be examined later as she got older.

Another night, up in my bedroom just over the living room, I woke up hearing something screaming out there in the darkness. It lasted only a few seconds—just long enough to know I wasn’t dreaming—and I wondered if it was a fisher cat out there, killing for its dinner, or maybe it was something else.

I was going to roll over and go back to sleep, when I heard the murmur of voices. Grandpa and Grandma were still awake, and I snuck out of bed and went to my open bedroom door. I could just make out a few words of what they were saying downstairs, and it was something like this:

“… you heard it too, Roger, don’t lie to me…”

“… an animal, that’s all…”

“…like hell…” which really scared me, because I had never heard Grandma curse before, and she went on, saying, “…you know that scream came from Henry Lee’s place…”

“…maybe he was having a bad dream… television too loud…”

“…you might think so, but tonight, the doors get locked…”

“…Millie…”

“….don’t Millie me…. the doors get locked…”

Then the voices were lowered, and I didn’t want to hear anymore, and I went back to bed.

• • •

So we went around the front of the house, and up the stone steps, and I was craving another cigarette but managed to push it aside. From Clara’s jacket pocket, she took out a huge key and worked it into the front door, which had an ornate handle that looked about a hundred years old and several glass panes covered by a curtain from the other side. The lock made a heavy chunk sound as it was undone, and the door creaked as she pushed it open.

“Here we are,” she said, like she was announcing the opening of a long forgotten Egyptian tomb, and being chicken, I know, I let her go in first. She went in and I followed, and she made to close the door behind us and I said quickly, “No, I’d rather have it open, please.”

“Whatever you say, Holly.”

What I wanted to say was let’s turn around and get the hell out, but I bit the proverbial tongue and walked in another couple of steps, memories roaring through my mind like a Cat Five hurricane. The kitchen was before me, the old and cracked linoleum still in place. There was a refrigerator in some ghastly green avocado color that was popular at a time when the nation’s sense of taste obviously went numb for a number of years, and there was still an old black stove, once a coal burner, that had been converted to natural gas.

Wallpaper on the walls had started peeling away in long, weeping strips. Clara started talking about the wonderful features, the hardwood floor that was underneath the linoleum, and how her brother-in-law could remove that wallpaper at hardly any cost at all. She went on with her selling points—and I was too polite to tell her that the sale had been made about a month ago, when I had first learned that the house was on the market—and I tried to calm down the memories that were coming at me. Over there had been a round kitchen table, I remembered that. To the right, the living room, where at night one could see the blue glow coming through the windows as Henry Lee watched his programs by himself. The living room was bare, save for a sickly yellow-looking shag rug that looked like a herd of baboons had urinated on it, and an old brick fireplace that had been swept clean, if years earlier.

Clara paused. “Would you like to go upstairs?”

Hell, no, is what I thought. “Why not?” is what I said.

• • •

About a week after the water-spraying incident, I remembered our little gang were sitting in a circle on a rise of land in Grandpa’s rear pasture, and Greg said, “Let’s go back to the warlock’s house.”

Penny started whimpering and said, “I’m going home now. No way I’m going back there.”

Even Sam and Tony didn’t seem too thrilled with the idea, but Greg being Greg said, “Anyone who doesn’t come is a chicken. C’mon.”

I remembered looking at Sam and Tony and standing up to say, “I ain’t no chicken,” then Sam and Tony suddenly recalled that they had to get home to help their dad with moving some firewood, so it was just me and Greg.

He trotted along the oil-covered dirt road until we came to the intersection where Henry Lee’s house was. It was early evening, right after dinner, and Greg said, “Look. He’s got the lights on again in his basement.”

Greg scampered across the street and I followed him, and like before, we crawled along the finely-mown grass until we reached the stone foundation. Greg whispered to me, “I’ll take the far window, you take the nearest one. We’ll spy for a while, okay?”

“Sure,” I whispered back, and I crawled closer and closer to the screen of the open window, knowing no matter what I saw, I sure as hell wouldn’t yell at Henry Lee. That had been dumb.

I got closer and closer and peered in, feeling my heartbeat bouncing off the ground that I was lying on. The light was strong and I blinked a few times, and then I had to bite my lower lip not to whimper. I looked down into the basement and could only see part of it, but I saw a long wooden worktable, with lots of brown bottles and small metal dishes. And tools. And old rags. Then Henry Lee limped into view, and he was naked. I saw his white skin and flab and scars, and his prosthetic leg, and I squirmed some, afraid I was going to pee myself. He was muttering something and he turned, and there were brown stains on his face and hairy chest.

Then he looked right up at me.

Right at me.

Stared. His lips curled back some, like an angry dog, but he didn’t say a word.

Just stared.

I knew I shouldn’t move, or do anything, but I couldn’t help myself. I slowly slid back until mercifully, Henry Lee and the inside of his basement went out of view. Greg slid over to me and said, “See anything?”

“No,” I lied. “I wanna go home.”

So we got off the lawn and trotted back, and then I remembered Greg saying, “Man, that’s strange. The warlock must be burnin’ something.”

I turned and from one of the chimneys, sparks and smoke were rising up into the night sky.

• • •

Upstairs wasn’t that upsetting, which pleased me. The rooms were empty and again, there was the peeling wallpaper, and more cracked linoleum on the floor. I remembered similar linoleum back at my grandparents, where they would put throw rugs down on the floor to make it easier to walk on in the winter, though in the summer, having cool linoleum on your feet felt so fine. Anyway, I was glad that whatever beds and other furniture had been up here had been taken away.

Despite Clara’s invitation, I refused to check out the upstairs bathroom.

And one more surprise. I looked to my eager real estate agent and said with a surprisingly strong voice, “Let’s go to the basement, all right?”

• • •

The summer dragged on, with that special delight that only happens when you’re young and out of school, with no real responsibilities or obligations. It was during one of the last weeks of August when it all fell apart, like one of those games you play with a deck of cards, trying to make a tower. You can make the tower, but it always falls down. That’s a given. Everything will eventually fall down.

It started out one dusk, as we were all sitting around in a circle again, except for Penny, who was out at some 4-H meeting. I don’t know how the talk started, but Sam was feeling frisky or something and started teasing me about being from Massachusetts. He said that his brothers all thought people from Massachusetts were soft, were losers, were real wimps who didn’t know how to drive, and who drank too much, and were sissies. Tony and even Greg chimed in, and I made the big mistake of saying something like, “Yeah, and who was the sissy who screamed like a girl when he got water splashed on him?”

So Tony and Sam and Greg started raising their voices, calling me names, calling me out, and I got mad, too, and Greg said, “You wanna prove you’re no sissy?”

“You bet,” I said. “I can do it.”

Greg looked pleased with himself, like he had caught me in something. “Then right now. You go up to the warlock’s house, to the porch, and you ring his doorbell. You do that, and then we’ll know you’re no sissy.”

I felt small and outnumbered and trapped, and I looked over at the lights of Grandpa’s farmhouse, where it was so very safe. I could walk back to that house right now and ignore it all, but the rest of the summer… I would be a sissy. That’s all. How could I come back next summer, with that insult stuck to me?

So sounding braver than I was, I said, “Sure, I’ll do that. And you can watch.”

Trying to get it done before I lost my nerve, I remembered I started running out of the pasture, up the dirt road to the warlock’s house, thinking all it would take would be to run up the porch, ring the bell, and then run back across the street, dive into some lilac bushes. That’s all. Then I wouldn’t be a sissy.

There. The house was right there. Lights were on upstairs, meaning that’s where Henry Lee—warlock or no warlock—was, so it would be simple to pull it off.

I looked back. The three boys were huddled together, watching. Greg stuck his hands in his ears, wiggled them, and with that, I trotted up the stone steps to the wide porch. The doorbell was right there, but I remembered feeling put off, to be shoved into doing something like this. So I turned around and wiggled my hands in my ears and stuck out my tongue at Greg and Sam and Tony, and when I turned to ring the doorbell and then safely run away, something grabbed my left shoulder.

• • •

The air coming up from the basement was cool and damp. Chickening out again, I let my enthusiastic real estate agent go ahead of me. The stairs were wooden and old, and creaked with every descending step. I followed her down, with each step the pressure on my chest increasing, like I was in some sort of submarine, going hundreds of feet down below the ocean. I had to duck my head at one point, and then I got to the bottom of the stairs, my legs actually trembling, and—

Nothing.

I looked around.

Well, not nothing, but there wasn’t much. The long wooden table I remembered from almost forty years ago was still there, but it was bare. No bottles, no tools. There were some old cans of paint on the cracked cement floor, but that was about it. Under the wooden stairs was a collection of firewood for the upstairs fireplace and a bag of kindling. There was a large pegboard on the other wall with rusty tools hanging from it. In one corner, there was an oil furnace and an oil tank. The posts that held up the floor, I found, were made from tree trunks.

It was an old, old house. I touched one of the posts. It didn’t look haunted, down here, not a bit.

Clara was talking some more, and I was tuning her out as I bit my lip and looked around the basement that had haunted me for so many, many years. There were the rough stones of the foundation, the two screened windows that I now found myself looking out of—instead of looking in—and not much else.

“So,” Clara finally said. “Anything else you’d like to see?”

“Not really,” I said. “Why don’t we go upstairs and sign the papers? Make this a done deal.”

If she played for the other team, I’m sure Clara would have kissed me full on the lips, that’s how happy she was, but she just grinned, and we went upstairs. I took one more look at the basement, empty and sad-looking, and felt almost a bit disappointed.

Outside, the sun felt good and we stood on the porch. I wrote Clara a check and we did some paper passing, and when the formal paperwork was over, I was given the heavy key. She looked a bit sheepish and handed over my latest published novel, Blood On the Floor, which I signed for her daughter: “To Mona, all best wishes, Holly Morant.”

Standing there, I felt the craving for a cigarette pass through me and go away, and I thought that was a pretty good sign. I saw a couple of kids, listlessly pedaling their bicycles back and forth, back and forth on the pavement, and I said to Clara, “When I was younger and came here, the roads were dirt and covered with oil, but you know what? We could play in the fields and the woods and have lots of fun. Now, it’s all developments and such. Where else could those kids go?”

Clara zippered up her leather bag with practiced ease. “Nowhere else, that’s for sure.” She looked over to me. “What do you plan to do with your house now?”

“Take some time to let it sink in. Then call you again. Maybe your brother-in-law could start working on the interior.”

Oh, that cheered her up some, and when it came time for me to leave, she shyly asked, “Can I ask you one more question?”

Even though I knew the question that was coming, I decided to be polite. “Go ahead.”

“Where on earth do you get your ideas?” she asked. “I mean… from what I know… all your books are full of nasty things, and blood, and terror, and death…”

The craving for a cigarette roared right back at me, and I snapped off an answer. “Oh, I subscribe to an idea service out of Poughkeepsie, New York. For five dollars a week, they send me a postcard with an idea for a novel. It works really well.”

When I was done with those words, I regretted it, for I could tell by the color in Clara’s face and the pursing of her lips, I had hurt her feelings. I briefly touched her wrist and said, “That was a wise-ass answer. I’m sorry. Look, tell me the most expensive restaurant in Mullen, and I’ll buy you lunch. As thanks for putting this deal together.”

Her mood quickly changed, like snapping from the History Channel to the Lifetime Channel. We both walked down the stone steps, and when I got to the bottom, I just had to do it. I turned and looked back up at the door.

• • •

I remembered screaming when the hand grabbed my shoulder, and I tried to pull away and run free, but it didn’t work. Henry Lee Atkins dragged me off the porch and into his kitchen. I twisted around, his hand firm on my T-shirt, and he bellowed, “What the hell do you think you’re doing, sneaking up on my porch!”

I couldn’t catch my breath, I was so scared. I was in his kitchen and he had on stained khaki shorts, no shirt, and his flab was old and leathery and furrowed with scars. Up close, his prosthetic leg looked scary, like some metal and plastic insect had grabbed hold of his leg and was chewing him up. His face had gray stubble on his cheeks and chin, and I tried to pull free again, but his hand was too strong, wrapped up in my T-shirt.

He shook his hand, making me tremble. “Who the hell are you? Are you one of the local kids, or are you from away? Hunh? Tell me right now!”

I managed to take a deep breath by then, and stammered out, “I’m from away… I’m not local… I didn’t mean to come up on your porch…” and I started crying, and said, “Please… let me go… I’ll go away… please let me go…”

My tears and pleas seemed to make him happy, for he grinned and said, “You’re from away? Really? Then no one’s gonna miss you, will they…”

He pulled hard on the T-shirt, started dragging me across the linoleum floor. One of my Keds sneakers popped free from my right foot. I was screaming, twisting, crying, and with his free hand, he opened the door to his basement. “Nope,” he said, “no one ‘round here’s gonna miss you…”

I saw the open door and it looked so dark and scary down in the basement. Then I remembered feeling paralyzed and ashamed and suddenly warm and wet, as my terrified bladder let go and I peed all over his kitchen floor.

Another bellow. “You stupid little bitch, what the hell did you just do?”

Right then, his hand loosened, like he was disgusted at what I had just done. I pulled hard one more time, and the T-shirt tore. I broke free and raced out of the kitchen, throwing the door open, and still screaming, and with a torn shirt, one sneaker and soiled shorts, I made it out of Henry Lee’s yard and out into the darkness, where I wrongly thought I would finally be safe.

• • •

By our parked vehicles, I lit up a cigarette, and inhaled it, and didn’t toss it down. Clara paused and I said to her, “I apologize for what I said back there, about ideas. That was a rude thing of me to say. What I should have said is… ideas come from everywhere. They really do. A half-remembered conversation. A newspaper clipping from a year ago. Old memories, sometimes ones you don’t want even to think about. But those old memories, they hang out and make trouble, and sometimes, the only way you can tame them is to write about them.”

Clara still stood there, like I was suddenly speaking in Vulgate Latin, and I said, “Do you know what I mean?”

She seemed embarrassed. “No, not really.”

I took another satisfying drag from my cigarette. “That’s fine. Let’s go have lunch.”

• • •

Twelve hours later, here I was, back at my haunted house after spending some time at my motel room. I had pulled my rental car some into an open space among some nearby trees, so it wouldn’t be spotted, for I didn’t want anybody in the neighborhood to know I had come back. I walked quickly along the back yards and now I was on the porch, heavy key in my hand. I waited, the craving for a cigarette slumbering inside of me.

“Okay,” I whispered. “Let’s do it.”

I unlocked the door and went inside. The kitchen flickered there before me, the now of a dusty room, lightly illuminated by a streetlight, and the then of a terrified nine-year-old girl, certain she was being dragged to the cellar, never to be seen again.

I took a deep breath. From inside my purse, I took out a small flashlight, switched it on. I went to the cellar door, opened it up, and went down a few steps, before I sat down on one of the wooden stairs. I slowly moved the small light around. Here is where it all began, I thought, where it all started. From the ghostly voices coming up here, to the time Greg thought he had been splashed by acid, to the night I saw a naked Henry Lee ambling about his basement, to that horrifying dusk when I had been captured, violated, almost dragged in here…

Damn. My knees were quivering. And for what? I’m no psychologist or psychiatrist, but from this house and this basement, I knew how it all came about. My two failed marriages, where I found it so hard to trust somebody, found it hard to enjoy the touch of another. To a life of being single, of being the kind daughter and the slightly nutty and spoiling aunt. To a writing career full of terrors that no doubt made my college instructors shudder at what they helped bring into the world, but which brought me financial security and fame.

I brought my legs up, hugged my knees, rocked back and forth.

And for what? Because of a brave little girl who had the bad luck to cross path with an old, cranky and one-legged vet, who probably just wanted to be left alone, and have a life of peace… and who was tormented and teased by the local kids. That’s all. No warlock. No evil. No badness.

Just an old guy who wanted to be left alone.

I looked around the basement again. It was now mine. Whatever my plans, whatever my desires to exorcise whatever ghosts or demons existed here by taking the place over and making it my own… it was beyond silly. It was now pathetic. I had a house I neither wanted nor desired, all to come back and face a demon that had never existed.

It was like being brought to the scariest place on earth, after years of wanting to face your deepest, darkest fears, and learning it had been entirely built and operated by the Walt Disney Corporation.

I wiped at my eyes. Felt sorry for the nine-year-old girl who had made a choice that had echoed over the years, that had ended up with this solitary woman, nearly ready to start her fifth decade alone.

I got up and went upstairs, looked to the kitchen and to the empty living room and its fireplace, and I started to walk out and—

Stopped.

Something was wrong.

Something wasn’t right.

Something didn’t make sense.

I turned again. One fireplace in the living room. Built right over the oil furnace in the basement.

But the house…. it had two chimneys.

Two.

I went back into the basement.

Breathing hard, hands shaking, I finally had to put the small flashlight in my mouth to keep the beam of light secure. I went to the other side of the basement, to the large pegboard. It took time, two broken fingernails, and a lot of cursing, but the pegboard finally swung open on hidden hinges. I flashed the light again to the interior, to the open woodstove, to a damp brick wall, to the—

Scarred and stained wooden table. Leather restraints. Chains. Handcuffs. Knives. Surgical instruments. At the base of the open woodstove, charred bones.

I stood there for what seemed to be forever.

And a voice from four decades ago, ringing in my ears: “You’re from away? Really? Then no one’s gonna miss you, will they…”

• • •

Twelve hours later, I was back at the address again, though this time, I had a hard time finding a parking spot. Before me were police cruisers, pickup trucks with flashing red lights in their grills, and pumper trucks from the Mullen Volunteer Fire Department, as well as from two other local towns.

I stepped over the rigid fire hoses and puddles, and looked up at the smoking rubble. It didn’t look like a house anymore. Just a heap of charred wood, shingles, and billowing clouds of smoke. My real estate agent found me and started talking. About how the fire had been going on for a while before anyone saw it. How strange it burned down just after we had visited it. And that her brother-in-law thought the old electrical wiring might have shorted out due to the lights we had switched on and off. And… and…

I looked at Clara and smiled. “Act of God. Don’t worry about it, Clara. I won’t back out on the deal. We negotiated in good faith. Something like this just happens, right?”

Clara nodded, looking suddenly relieved. She wiped at her brow and said, “What are you going to do now? Rebuild?”

Oh, how happy I was, looking at the rubble, the flames shooting up, thinking of how purifying fire can be when it’s used right. I looked across the street, to where a group of the neighborhood kids had gathered. I said, “Your brother-in-law. Does he know landscaping?”

“Some,” Clara said.

“How does a park sound, for the local kids? Get the debris razed, put in a playground or something. Someplace fun.”

I unzipped my purse, took out my lighter and cigarettes. “And safe. Whatever’s built here, has to be safe.”

Clara nodded. “I understand. Oh, Holly, I’m so sorry…” She looked over at the fire crews, wetting down the charred timbers. “Do you think they’ll ever find the cause?”

I took out my lighter, flicked it open and saw the tiny flame shoot up. “I doubt it.”

Then I lit my cigarette, and for the first time in a long time, let it fall to the ground, unsmoked.

To order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Brendan DuBois of Exeter, New Hampshire, is the award-winning author of nearly 130 short stories and sixteen novels. His short fiction has appeared in Playboy, Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and numerous anthologies including The Best American Mystery Stories of the Century, as well as the The Best American Noir of the Century. His stories have won two Shamus Awards from the Private Eye Writers of America and three Edgar Award nominations from the Mystery Writers of America. He is also a one-time “Jeopardy!” gameshow champion.