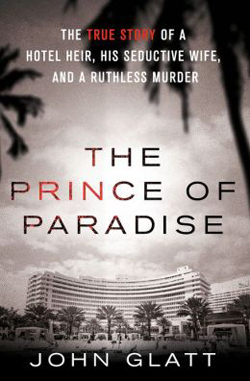

The Prince of Paradise by John Glatt is narrative nonfiction, the true crime story of the murder of Ben Novack, Jr., in Miami Beach (available April 16, 2013).

The Prince of Paradise by John Glatt is narrative nonfiction, the true crime story of the murder of Ben Novack, Jr., in Miami Beach (available April 16, 2013).

Introduction

When retired police chief James Scarberry heard in July 2009 that Ben Novack, Jr. had been brutally murdered, with his eyes gouged out, he was not surprised. On the contrary, he had foreseen the event seven years earlier, when he told his old friend to leave his beautiful wife, Narcy, or he would die. Scarberry’s warning came after the former Ecuadorian stripper hired thugs to beat up her wealthy forty-six-year-old husband, whose father had founded the legendary Fontainebleau hotel in Miami Beach. After mercilessly binding and gagging him with duct tape, the hired hands had held him at gunpoint for twenty-five hours while Narcy ransacked the family home. On her way out, Novack’s forty-five-year-old wife boasted that she could have him killed anytime she chose. “If I can’t have you, then no one will have you,” she snapped at him. “You’re not dead now because I stopped them.” Then she disappeared with more than $400,000 in cash and Novack’s collection of Batman collectibles, worth millions. After breaking free, Novack first called Chief Scarberry, who had once worked security for Ben Jr.’s father at the Fontainebleau. Scarberry then used his contacts in the Fort Lauderdale Police Department to launch a criminal investigation.

An active member of the Miami Beach Police Department Reserve and Auxiliary Officer Program for more than thirty years, Ben Jr. told detectives that Narcy had organized the home invasion and that he still feared for his life. Then he hired a lawyer and initiated divorce proceedings.

When brought in for questioning, Novack’s statuesque wife told detectives another story. She claimed that they were both into hardcore sexual bondage and had been role-playing. The one-time exotic dancer then stunned detectives by emptying out onto a table a brown accordian file full of her husband’s huge collection of amputee porn magazines, including his own photographs of naked disabled women.

Within hours of Narcy’s police interview, Ben Novack Jr. had called off the divorce, refusing any further cooperation with detectives. Then he welcomed his wife back into their home, explaining to police that they had started marriage counseling to get their relationship back on track.

Baffled friends wondered if Narcy was blackmailing him by threatening to reveal his bizarre sexual secrets and ruin his thriving $50-million-a-year convention business.

“I told him,” recalled Scarberry, “Benji, you’re nuts. This girl could have had you killed, and you’ve got to get out of that relationship.”

Ben Novack Jr. had refused to listen, so Chief Scarberry ended the friendship, and the two had not spoken since.

It was ironic that Ben Novack Jr. should die in a hotel room, for, a half century earlier, his father, Ben Sr., had built and run the legendary Fontainebleau hotel, transforming Miami Beach into the glamour capital of America and drafting the blueprint for today’s Las Vegas.

Benji, as everyone knew him then, had grown up in the luxurious seventeenth-floor penthouse, pampered by nannies and fussed over by the likes of Frank Sinatra, President John F. Kennedy, Bob Hope, and Ann-Margret.

“He was the Prince of the Fontainebleau,” explained his cousin Meredith Fiel. “Anything that Ben Jr. wanted, Ben Jr. got.”

Chapter 1: Coming to Miami Beach

One hundred and ten years before the home invasion, Ben Novack Jr.’s paternal grandfather, Hyman Novick, first arrived in New York from Russia, seeking a new life. The poor Jewish teenager, who spoke only Russian and Yiddish, married a girl named Sadie, who was six years his junior. Sadie was first-generation American, born in New York from Russian parents. The young couple settled down in Brooklyn, and Hyman, a cloth cutter by profession, opened a clothing store. In 1903, when Hyman was twenty-?ve and Sadie nineteen, they had their ?rst child, Miriam. A year later they had a son they named Joseph, followed in 1905 by another daughter, Lillian. Two years later, Sarah gave birth to Benjamin Hadwin, who completed the family. Between the 1910 and 1920 censuses, Hyman Novick lost his clothing shop and was reduced to driving a New York City taxi cab. Sadie was a homemaker, but their eldest daughter, Miriam, age seventeen in 1920, supplemented the family income by working as a stenographer. According to the 1920 census, twelve-year-old Benjamin and his older siblings could all read and write. A few years later, Hyman moved his family to the Catskill Mountains and went into the resort hotel business. He and Sadie founded and operated the Laurels Hotel and Country Club on Sackett Lake, five miles from Monticello, in the heart of what would soon become the “Borscht Belt.”

All the Novick children helped out with the hotel, which was soon thriving. They worked in various capacities, with Ben at the front desk and his big sister Lillian in the kitchen.

As a young boy, Ben almost drowned in the Laurels outdoor pool, an incident that resulted in his having to wear a hearing aid for the rest of his life.

After their father died in the mid-1930s, Ben and his elder brother, Joseph, took over the hotel. But they argued and soon split up, with Ben moving to New York City and going into the retail haberdashery business with a man named Kemp.

The handsome Ben arrived in the city in the midst of the Great Depression. To get ahead, he Anglicized his name to “Novack.”

He and Kemp opened a clothing store on Sixth Avenue called Kemp and Novack, but it was short-lived. Brusque and arrogant, Ben Novack soon fell out with his partner, and the two sold the store and went their separate ways.

It was during this time that Novack first met a young retail store designer named Morris Lapidus, who would later play a pivotal role in designing the Fountainbleau hotel.

“I believe [Ben] was also in the black market tire business,” said Lapidus’s son, Alan. “But my father never elaborated on that.”

Two thousand years ago the Tequesta tribe ?rst settled South Florida. They stayed until the sixteenth century, when explorer Juan Ponce de León arrived, claiming the land as a Spanish colony. In 1763, Spain handed Florida to Great Britain in exchange for Havana, Cuba. Twenty years later, Britain returned Florida to Spain in return for the Bahamas and Gibraltar. After the American War of Independence, Spain ceded Florida to America as part of the 1819 Adams-Onis Treaty, making it part of the United States.

Seventy years later, a rich Cleveland widow named Julia Tuttle bought 640 acres on the north side of the Miami River. In 1895, Tuttle persuaded Standard Oil tycoon Henry Flagler to bring his railroad to Miami and build a new town with a luxury hotel. On July 28, 1896, a few months after the railroad arrived, the City of Miami was officially incorporated.

If Julia Tuttle was Miami’s mother, Carl Fisher was undoubtedly the father of Miami Beach.

Born in Indianapolis in 1874, Fisher made a fortune co-inventing Prest-O-Lite, the acetylene gas used in car headlights for night driving. After selling out to the Union Carbide Company for millions, Fisher devoted himself to the new sport of auto racing, buying the Indianapolis Speedway in 1909 and making a second fortune.

Three years later, Fisher moved to Miami, coming to the rescue of a New Jersey avocado grower, John Collins, who had begun constructing a two-and-a-half mile wooden bridge between mainland Miami across the causeway to Ocean Beach, to bring his avocados to market. Unfortunately, when the bridge was only half finished, Collins ran out of money. So Fisher struck a deal to lend him the $50,000 he needed to finish, in return for two hundred acres of uninhabited swampland Collins owned on the island.

Thus, on a handshake, was Miami Beach born.

Jane Fisher would later claim that the first time her husband set foot on the beach, he picked up a stick and drew a diagram in the sand, declaring that he would build the world’s greatest resort on that very site.

Although the conditions were daunting (horseflies, snakes, and rats), Fisher’s vision knew no bounds. He purchased another 210 acres and, over the next few years, set about taming the wild, primeval terrain. First he drained the swamps, pouring in acres of sand to form solid new ground on which to build. His motto: “I just like to see the dirty.”

At ?rst Fisher couldn’t even give his Florida real estate away, as nobody wanted to live there. So he staged a whacky publicity stunt to turn Miami Beach’s fortunes around.

In 1921, president-elect Warren Harding was vacationing in Miami Beach when Fisher arranged to have a baby elephant named Rosie be Harding’s golf caddy as a photo opportunity. The press loved it, and a picture of the smiling future president and his pachyderm caddy on Miami Beach made the front pages coast to coast. The shot caused an immediate sensation, transforming Miami Beach overnight into “a place you had to see to believe.”

Fisher also persuaded his eclectic circle of friends—which included mobster Al Capone, newspaper publisher Moe Annenberg, and racehorse owner John Hertz—to build spectacular winter homes on the beach.

From 1920 to 1925 there was an unprecedented land boom in Florida,with Miami’s population almost quadrupling. In 1925, Fisher’s estate was valued at $100 million, and he celebrated by constructing Lincoln Road as the jewel of his Riviera resort.

The following year, Fisher turned his sights on replicating his success in Montauk, at the eastern tip of Long Island, New York. But this endeavor never took off and, along with the Great Depression, virtually wiped him out.

By the time Ben Novack arrived with his new wife, Bella, in February 1940, using the $1,800 he had received from liquidating his and Kemp’s New York clothing store, Miami Beach was thriving. The rest of America might have been struggling in the Great Depression, but Miami Beach had become the winter retreat for the rich and famous. In 1941 the Duke and Duchess of Windsor vacationed there, attracting worldwide publicity in the wake of Edward’s abdication from the British throne. Other famous regulars included Walter Winchell, Damon Runyon, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Miami Beach had recently been dubbed “the ultimate Babylon” by influential New York Tribune columnist “Luscious” Lucius Beebe, and Ben Novack was determined to exploit it for all it was worth. But, initially, he was uncertain where to begin.

Legend has it that he started out selling expensive watches to the wealthy tourists and snowbirds now flocking to Miami Beach in the winter. He also dabbled in the import-export business, reportedly running a fleet of banana boats to and from Cuba. Before long, he gravitated back to the hotel business he had grown up in.

With his silver tongue, Novack easily persuaded some business partners to put up $20,000 for a one-year lease on the Monroe Towers on Collins Avenue at Thirtieth Street. He then spent a year fixing up the 111-room hotel, while Bella worked as a chambermaid.

Then everything changed.

World War II broke out, making Ben Novack rich beyond his wildest dreams.

In February 1942 the U.S. Army took over Miami Beach, using it as a basic training center for troops before they were shipped off to Europe. With its perfect weather conditions, Miami was the ideal place to train pilots and rehearse the Normandy invasion.

Almost overnight, an estimated hundred thousand men from the Army Air Corps and the U.S. Navy invaded Miami Beach, and nearly two hundred hotels were requisitioned to billet them. The U.S. government generously compensated hotel owners up to $10 a night ($141 today) for each room, not including food.

“Boy, did my dad clean up,” Ben Novack Jr. told author Steven Gaines in 2006. “He raked in the pro?ts, and he did so well that he got another hotel and did the same thing, and then another hotel with an army contract.”

Ben Novack used his pro?ts to buy a share in the Monroe Hotel before snapping up the Cornell Hotel and then the Atlantis, which became an army reception center. Over a five-year period, he bought up five hotels.

Of Ben’s housing soldiers, Novack’s future sister-in-law, Maxine Fiel, remembered, “He told me, ‘I don’t have to feed them. I don’t have to give them anything. Just a bed.’ And that’s how he made his money.”

As he prospered, Novack carefully cultivated his own unique sense of style, becoming rather a dandy. He began wearing elaborate bow ties and draping custom-made brightly colored suits over his lithe five-foot, six-inch frame. Every morning, his personal barber trimmed his thin mustache the French way.

Novack took great pride in his appearance. It would be the same approach he would later bring to his hotels.

At the end of the war, Novack went into partnership with Harry Mufson to build the Sans Souci, boasting that the new hotel would “wow” guests. Novack envisioned it as the last word in elegance on the ocean, with its own restaurants, shops, and a penthouse nightclub with fabulous views. Its French name, Sans Souci (meaning “without care”), he felt, would add a touch of class.

Ben Novack saw hotels as pleasure palaces straight out of a Busby Berkeley musical. He dreamed of transforming Miami Beach into an unparalleled paradise, like no other place in the world.

In the spring of 1945, his ambitions knew no bounds when he strolled into Manhattan’s La Martinique nightclub and first set eyes on top photographic model Bernice Stempel.

Chapter 2: Bernice

Bernice Mildred Stempel was born on December 2, 1922, on New York’s Upper West Side. Her father, William Jack Stempel, had emigrated to America from London some years earlier.

The Stempels settled in New York and young William, whom everyone knew as Jack, grew up to become a successful furrier, dressing Manhattan’s elite. Handsome and athletic, he was a welterweight boxing champion and a bon vivant, who liked the good life.

“He was a playboy,” recalled his youngest daughter, Maxine Fiel.“He was a guy that knew all the politicians in New York and had his own card games.”

One day, Stempel was in Gloversville, in upstate New York, during one of his frequent fur-buying trips to Canada. He stopped off at Worth’s department store, where he saw a beautiful young Irish salesgirl named Rowena Sweeney Burton.

It was love at first sight.

“He thought she was just unbelievably gorgeous,” said Maxine. “Red hair and blue eyes. And when my father wanted something, he was like a dog with a bone.”

Over the next few months, the thirty-six-year-old Stempel, who was Jewish, assiduously courted the twenty-one-year-old devout Irish Catholic. When he proposed marriage, she readily agreed.

After the wedding, he moved his new bride to Manhattan, installing her in his spacious West End Avenue brownstone. He then went into the insurance business and made a fortune.

In 1922 their ?rst daughter, Bernice, was born, followed by Maxine, two years later. Rowena insisted on having the babies baptized Catholics.

Now a father, Jack Stempel did not allow his new family to cramp his playboy lifestyle in the slightest. He was already well known in New York society, cultivating influential friends and gambling away his nights in the speakeasies during Prohibition.

“He’d go out,” said Maxine, “and do the same things as if he was unmarried. So he left [our mother] alone.”

One day, Jack asked his best friend to keep his wife company nights, while he went out on the town.

“That was fatal,” said Maxine. “He left her alone, and his friend, who was a salesman, was interested in her.”

When Stempel discovered that his wife and best friend were having an affair, he threw Rowena out of the house and filed for divorce.

“It was all over the papers,” said Maxine, “because my father was very prominent.”

Jack Stempel won custody of his young daughters, but sent them to live with his two sisters. He refused to let their mother have any further contact with them. Rowena tried to ?ght for custody, but she had no money to challenge her ex-husband’s expensive attorneys.

After a few months, Bernice and Maxine’s aunts could no longer take care of them, so the sisters were sent to an orphanage. They were eventually fostered out to a German family named Reiser, who owned a restaurant in Far Rockaway, in Queens.

Bernice was a nervous child, and was so traumatized by her parents’ bitter divorce that she withdrew into her own world.

“Bernice was older, but I always took care of her,” said Maxine. ”She wouldn’t speak up, and I always had to.”

In the early 1930s, divorce was rare. Most people stayed together, making the best of a miserable marriage. Bernice and Maxine Stempel, therefore, had a difficult childhood, growing up under the stigma of their parents’ divorce. This tough childhood took a toll on Bernice, leaving scars for years afterward.

Their foster parents sent the girls to public school in Washington Heights, where their mother would try to visit them.

“She would come to the schoolyard to see us,” recalled Maxine. ”She was gorgeous. I adored her.”

They missed their mother terribly, but spent the holidays with their father and his family. He would never let them see their mother, who eventually ended up in a mental health facility.

Both Stempel girls were unusually beautiful, turning heads wherever they went. They were skinny and pale, with striking red hair and freckles that they had inherited from their mother.

When Bernice was ten years old, an uncle recommended that she and her sister become millinery models for the big New York department stores.

“He was a buyer for a big ?rm,” said Maxine, “and he suggested we go into [modeling], because he said you girls are so beautiful.”

The uncle found them jobs modeling hats, jodhpurs, and other riding out?ts for society out?tters in Manhattan, but they were paid a pittance.

At public school, Bernice was a good student with a talent for stenography. She was also a natural rebel, and often cut classes.

When she left school, Bernice was headed for a secretarial career, until she was spotted in the street by a talent scout for the famous Conover Model Agency, who immediately signed her to their books.

By 1940, Conover was the top fashion model agency in New York. It was founder Harry Conover who had invented and trademarked the term cover girl, and who headed a stable of the most beautiful models, specializing in the “well-scrubbed” natural American girl look.

The handsome and charismatic Conover turned his “girls” into the ?rst supermodels, giving them suggestive professional names such as Choo Choo Johnson, Jinx Falkenburg, Dulcet Tone, and Frosty Webb.

After signing with the Conover agency, Bernice Stempel soon went to the top. Her natural red hair and cream skin made her one of his most sought-after girls. Overnight, the once-insecure girl was reborn as a poised, sophisticated young woman whose breathtaking beauty won her a string of lucrative modeling assignments.

“It helped her get self-esteem and to be validated,” explained Temple Hayes, later to became a close friend. “She and her sister had started out in an orphanage, so it was wonderful for her to have those kind of doors open. And she was proud of surviving such a horrific [childhood].”

In the mid-1940s, Bernice moved into her own apartment with another model, and started going out on the town with her new, glamorous friends. At one party, she was introduced to Salvador Dalí, who immediately invited her to come to his studio and model for him.

When she arrived and the middle-aged surrealist ordered her to strip naked for a portrait, she fled.

“He wanted her to pose nude, and she refused and walked out,” said Estelle Fernandez (not her real name), who would later become Bernice’s best friend. “She told me he was absolutely crazy and he tried [to take advantage of her]. She would never use her body or do anything to [get ahead].”

Although many advertising directors employed the casting couch approach, Bernice Stempel never resorted to these measures to get modeling assignments.

Throughout the 1940s, she regularly modeled for Coca-Cola, as the clean-cut American girl in many of its ad campaigns. She also worked for Old Gold cigarettes, with her long shapely legs tap-dancing under a king-size pack in a popular commercial of the time.

Bernice was a regular at the ultra-exclusive Stork Club, becoming a favorite of its charismatic owner, Sherman Billingsley. She was also pursued by a string of admirers, some of whom proposed marriage.

“She went out with some very wealthy guys,” recalled her sister, Maxine, “but she ended up marrying a nice middle-class good guy.”

Arthur “Archie” Drazen was anything but a playboy, but Bernice fell for his charm. After they married, they settled down in a modest apartment at One University Place, Greenwich Village, overlooking Washington Square Park.

Then Drazen went off to Europe to ?ght in World War II, leaving his beautiful model bride alone in Manhattan, with all its temptations.

Copyright ©2013 John Glatt

For more information, or to buy a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()