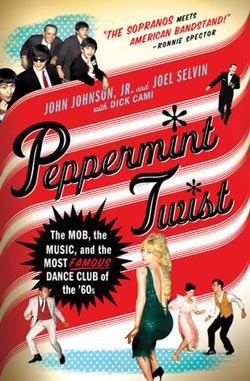

The never-before-told story of The Peppermint Lounge, the famed Manhattan nightspot and mobster hangout that launched an era.

The Peppermint Lounge was intended to be nothing more than a front for gambling and other rackets, but the club became a sensation after Dick “Cami” Camillucci began to feature a new kind of music, rock and roll. The mobsters running the place found themselves juggling rebellious youths alongside celebrities like Greta Garbo and Shirley MacLaine. When the Beatles visited the club, Cami’s uncle-in-law had to restrain a hit man who was after Ringo Starr because his girlfriend was so infatuated with the drummer.

Working with Dick Cami himself, Johnson and Selvin unveil this engrossing story of the Go-Go ’60s and the club that inspired the classic hits “Twisting the Night Away” and “The Peppermint Twist.”

Ground Zero

Dick Cami was lounging by the pool at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach mid-October 1961 when he got the call from New York. Something about celebrities, socialites, and other A-listers crowding into the off-Broadway dive that his father-in-law and his boys owned on West 45th Street.

The teen dance club didn’t have a phone. The boys were smart enough not to have one because that way it couldn’t be tapped. When Dick called back, he had to dial a pay phone that rang in the Knickerbocker Hotel lobby, which was right outside the club’s back door. He was not surprised to hear a flirtatious woman’s voice come on the line. The Knickerbocker these days rented as many rooms by the hour as they did to the luckless out-of-towners, the unemployed, and those only a week away from living on the streets.

“Hi, honey,” Cami said. “Do me a favor and stick your head in the door behind you, the one to the Peppermint Lounge, and ask for Louie or Sam.”

The girl hesitated. “There’s a big guy blocking the door.”

“Tell him to come to the phone—please.”

A moment later, the gruff voice of the Terrible Turk came on the line.

“Who is it?”

“Turk, it’s me, Dick.”

“Dickie, holy shit, you can’t believe what’s happening here.”

The Turk was a former professional wrestler with a shaved head and a body that looked like it’d been stamped out on a truck assembly line. In a tuxedo, he looked official, and officially dangerous.

“It’s fucking unbelievable, I tell you. They put me on the back door because we got so many people trying to sneak in through the fucking hotel lobby. You guys coming up or what?”

“Soon,” Dick said. “Get me Louie, will you?”

“Sure, hold on. He’s on the other side, giving an interview to a newspaper guy.”

Holy shit, Cami thought. Louie Lombardi giving an interview? About what? Breaking arms? Making book? Buying swag? Jesus, that’s all we need.

Finally, Louie’s voice came on the phone. “You guys don’t want to listen to me? I’m telling you, this joint’s exploding. You know who I was just looking at?”

“Who?”

“Greta Garbo. That broad that wants to be left alone.”

This was too much for Cami, who laughed and said, “Greta Garbo? She doesn’t go anywhere; it must be a look-alike.”

“Look-alike my ass,” Louie said. “This broad is Greta-fucking-Garbo, I’m telling you. And she’s here tonight. You guys are the only ones that ain’t here.”

Dick looked up to see his father-in-law coming into the beach cabana. Dressed immaculately in a black silk shirt, custom ivory trousers, alligator belt, and matching shoes, Johnny Biello created a barely noticeable ripple of excitement among the pool boys and sunbathers. They couldn’t know that he was a high-ranking mafioso, caporegime of the Genovese crime family, at one time considered the most likely heir to Frank Costello’s unofficial title of prime minister of the Mob.

But they did know, by the way he carried himself, that he was somebody you stepped out of the way for.

“It’s Louie again, I think we better go up,” Cami said.

Johnny nodded. “Okay. Get the tickets,” he said.

After Dick and Johnny landed at LaGuardia and grabbed their bags, Dick hailed a cab. When he leaned forward to give directions, Johnny put his hand on his shoulder and cut him off.

“Take us to the Peppermint Lounge,” he said.

Dick shot him a look of disbelief. What airport cabbie was going to know the Peppermint?

“You kidding me?” the driver said. “We won’t get within blocks of that place.”

After deciding to take the cab into Manhattan and abandon it on the East Side, the two men made their way across 45th Street. Traffic was stopped dead between Fifth Avenue and Broadway. Long before they got to the Peppermint, they could see what looked like a street riot up ahead. Floodlights cut the night sky and the sounds of the noisy crowd bounced off the skyscrapers.

Cops had erected barricades and a small battalion of mounted police tried to steady their spooked horses while driving back an exuberant, barely controllable mob onto the sidewalk. At the entrance, a parade of limos dispensed women in gowns and men in tuxes.

The line waiting outside the candy-striped awning was a full sidewalk wide. It stretched all the way down to Broadway and beyond. The din of rock-and-roll music grew louder and became more distinct as the line approached the Peppermint’s entrance.

Johnny led the way to the front door, where they were met by Lenny Montana, a six-foot-six flesh monolith known as “the Bull” during his time as a professional wrestler. Years later, he would be better known as the murderous Luca Brasi, Marlon Brando’s bodyguard in The Godfather. Montana flashed a big grin and cracked open the door, leaving the waiting throngs buzzing with curiosity over the identities of the two men. Politicians? Movie moguls? High rollers?

Inside, the dim light made it hard to see. They made their way along the rope separating the long mahogany bar in the front. Three bartenders worked as fast as they could, shouting themselves hoarse and opening bottles of Chivas every few minutes. Customers were too thrilled to have made it inside to notice the acrid taste of the cheap booze Scatsy had substituted for the Chivas—a practice from his bootlegging days in the twenties, when he and his brother Johnny worked for the Dutch Schultz mob.

At the end of the rope was the back of the club, where Joey Dee and the Starliters were blasting “The Twist” from a raised bandstand. The dance floor, just eight by twenty feet, was packed with shuddering, shimmying bodies. Mirrored walls bounced their images to infinity, jammed together, asses to elbows, moving to deafening rock-and-roll music. No two dancers moved the same way, but all were doing a version of the Twist.

As Dick’s eyes adjusted, he could see that Louie was not imagining things. Sitting at the edge of the dance floor with several handsome young hangers-on was Ava Gardner, one of Hollywood’s leading screen queens. Gardner got up and nearly shook the bolts out of her chassis. Dick decided she’d had too much to drink. At the next table was Shirley MacLaine, one of the day’s best young actresses. MacLaine laid claim to the dance floor, shaking and twisting like a pro. Spotting her, Joey Dee jumped down from the bandstand and wriggled alongside her.

If the Peppermint burns down tonight, Dick thought, only half of New York society will go with it. The other half was still waiting on line outside.

Johnny had connections to numerous businesses. Some he had on the arm, which meant the owners paid him to keep anyone else from doing to them what he was doing to them. Some he owned, often registering a legitimate partner’s name on the license. Some he used as fronts, holding strategic meetings and conducting his illegal activities in the back rooms. The Peppermint Lounge he owned and used as a front. When the club became the most-asked-about New York City attraction at the Times Square information booth, the attention was neither expected nor welcomed. Drawing squads of cops, hordes of teens mixed with society types, and noted celebrities to this club or any of his business connections was never in his plans. Johnny Biello lived quietly, respectably, and always in the background.

The reason he had moved to Miami three years earlier, uprooting not only his family but also son-in-law Dick’s was to distance himself from day-to-day life in gangland New York. After Frank Costello was shot, Johnny knew things in the Mob would never be the same for him and he wanted to retire. He had a great business opportunity in Florida and, while not entirely legit yet, that was the dream.

At age fifty-five, he had survived a lifetime of Mob wars, FBI investigations, and criminal prosecutions. He wanted out, but extricating oneself from the highest levels of organized crime in the Five Families of New York was no simple matter. Having the entire Western world’s eye trained on the teenage rock-and-roll dance club he owned on 45th Street was not going to help. Johnny decided that it would be better to play it safe and stopped any illegal activities out of the Peppermint. But Johnny was no fool, either. Sensing an opportunity after witnessing firsthand the nightly madness that followed the club’s meteoric rise, he decided to return to Miami Beach and open a second, all-new and completely legitimate Peppermint Lounge as quickly as possible.

October 1961

The new president and his glamorous wife had not been installed in the White House ten months yet and the Cold War was heating up to a brisk boil. Soviet troop buildups in Berlin were reported. As tensions grew between the two former allies, New York governor Nelson Rockefeller called for fallout shelters to be built in public schools.

President Kennedy dispatched General Maxwell Taylor to a small Asian country called South Vietnam to study means to assist the country’s struggle against communism, although the general hinted on the eve of his departure that he would be reluctant to commit U.S. troops.

October began with New York Yankees outfielder Roger Maris breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record on the last day of the season. The Yanks went on to defeat the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series, with ace Whitey Ford pitching fourteen shutout innings. Downtown, New York City mayor Robert Wagner and attorney general Louis J. Lefkowitz were locked in a bitter election brawl, each claiming the other was not qualified to run the city.

The 1962 automobile models were in the showrooms. The new Rambler Ambassador V-8 Custom Cross-Country offered optional Lounge-Tilt driver’s chairs. The 1962 Chrysler Newport featured torsion-bar suspension and unibody construction for $2,964. The age of jet air travel was dawning; Pan Am asked $350 for round-trip airfare to Europe.

Old-timer Rudy Vallee was making a comeback attempt with a new musical opening that month on Broadway, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. British playwright Harold Pinter was opening his play The Caretaker at the Lyceum with a cast that included Donald Pleasence, Robert Shaw, and Alan Bates.

The film version of West Side Story starring Natalie Wood was opening at the Rivoli. Breakfast at Tiffany’s with Audrey Hepburn was already a big hit at Radio City Music Hall. The Devil at 4 O’Clock was the new Spencer Tracy–Frank Sinatra movie. Bonanza, starting its third season that September, was the most popular show on television, but it would soon be challenged by newcomers The Dick Van Dyke Show and Ben Casey, a series about a young hospital intern, starring Elvis Presley look-alike Vince Edwards.

Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird topped bestseller lists, along with Irving Stone’s fictionalized life of Michelangelo, The Agony and the Ecstasy. Hot nonfiction tomes included Theodore White’s The Making of the President 1960 and William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.

But a fever gripped New York in October 1961. The most important pop music event between the emergence of rock and roll and the arrival of the Beatles—a new dance called the Twist—hit Manhattan that fall. In a matter of weeks, the craze altered the social landscape. Everybody—adults, kids, politicians, and garbage collectors—was suddenly doing the Twist.

A deceptively simple dance consisting of swiveling hips and shifting feet, the Twist was the real beginning of the sixties. The seeds to the black power movement, student protest, psychedelics, draft card burnings, Woodstock—everything that became the sixties—can be seen in the coming of the Twist, and the breaking-the-mold freedom it promised.

Dance crazes had come and gone before, almost always greeted with some measure of controversy. Fifty years earlier, the Turkey Trot was an obsession with youth of the gilded age. The editor of Ladies Home Journal was reported to have fired fifteen young ladies for Turkey Trotting during their lunch hour. The Tango was denounced when it appeared in 1914. Vernon and Irene Castle, a popular brother-sister dance team, introduced the Castle Walk, in part to stem the orgy of Turkey Trotting.

The Charleston, from a song by pianist James P. Johnson in the 1923 Broadway musical Runnin’ Wild, became the dance craze of the Jazz Age, a raucous fling with lustful abandon to a ragtime beat. The Lindy Hop burst out of Harlem in the thirties, incorporating some of the swivels and steps of the Charleston, but strictly within the context of Lindy Hopping, which was a hallmark of swing-era dance floors.

None of them generated the combination of frenzied excitement and moral outrage with which the nation greeted this new dance. Black Panther Party firebrand Eldridge Cleaver credited the Twist with teaching white America to shake their asses. Canadian sociologist Marshall McLuhan, not averse to doing the Twist himself, pronounced the dance “very cool, very casual, like a gestural conversation without words.”

By changing the way people danced with each other, the Twist had ramifications beyond the dance floor. Because each dancer was an independent contractor, women were liberated from having to follow their partners and, in that way, the dance cracked open the door ever so slightly to the women’s movement and sexual liberation yet to come.

The Twist was sexy. At a time when coyly posed topless models in Playboy magazine were racy fare indeed, the sight of a woman churning her hips and spreading her legs in public was something new to polite American dance floors. The dance’s proponents loudly and unconvincingly proclaimed innocence—describing the dance as good exercise and wholesome fun—but its erotic content was not the least of its secret appeals and maybe the most. It was not open rebellion—not yet—but the Twist represented the stiffest challenge to the established order and the rules governing public behavior since the end of the Second World War.

The list of detractors was long and vocal. “Not for me,” said Fred Astaire, America’s foremost dancer, whose nationwide chain of dance studios soon enough began offering Twist lessons. Television’s Jackie Gleason called it “a silly jiggle for amateurs that will last about as long as chlorophyll.” Nat King Cole sang “I Won’t Twist” on the Dinah Shore TV variety show. The dance was not allowed at society events.

“The Twist is not a social dance and we won’t permit it,” said Mrs. Douglas Williams of the Grosvenor Ball.

Lou Brecker, proprietor of Midtown’s Roseland Ballroom, also banned it. “It is not, in our opinion, a ballroom dance,” he said. “It is lacking in true grace and since we have previously outlawed rock-and-roll as a feature at Roseland, we likewise will not permit the Twist to be danced.” The education writer of The New York Times fumed, “Instead of youth growing up, adults are sliding down.”

Critics went so far as to declare the Twist a health hazard. The Chiropractic Research Council noted that forty-nine cases of “Twisters back” were reported in a single week in New York. “The dance puts unusual stress on the soft tissues of the lower spine just below the pelvis and can cause serious damage,” said Dr. Thure Peterson of the Chiropractic Institute of New York. “Twisters are leaving themselves open to charley-horse-like pains and spinal spasms.”

The issue was debated in side-by-side columns in The New York Times Magazine. “The Twist? I’m sitting this one out,” wrote Trinidad-born dancer Geoffrey Holder. “It’s dishonest. It’s not a dance and it has become dirty. Not because it has to do with sex. Everything does. But it’s not what it’s packaged. It’s synthetic sex turned into a spectator sport. Not because it’s vulgar. Real vulgarity is divine. But when people break their backs to act vulgar, it’s embarrassing.”

“In defense to the charge that the Twist is lewd and ‘dirty,’ I can only say that any movement can be made to appear suggestive, depending on the dancer himself,” responded Chubby Checker, whose recording of “The Twist” was rocketing up the charts that winter. “I have often watched couples Waltzing or doing a Fox-Trot and have been more embarrassed than when viewing the most uninhibited Twisters.”

Besides being a signal event in the history of American popular dance, the Twist was a landmark in the history of popular music. It arrived at a time when the rock-and-roll movement, which had struck so forcefully five years earlier, was losing momentum, pandering to a strictly teenage market in ever more venal, insipid ways. The fierce warriors of rock-and-roll’s initial assault—Elvis, Little Richard, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers, Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, and the others—had largely fallen by the wayside. In their place, freshly scrubbed, homogenous white males with sculpted hair were paraded before an eager public tuned to television’s American Bandstand, a three-hour after-school broadcast from Philadelphia hosted by an equally clean-cut, clear-eyed disc jockey named Dick Clark.

Old-time, blue-chip music publishers couldn’t get arrested and kids barely old enough to drink were writing hit after hit. The power shifted from the old guard at the Brill Building, where big bands from Duke Ellington to Tommy Dorsey kept their offices alongside music publishers of the era, to 1650 Broadway, an office building two blocks away that housed the budding rock-and-roll empires like Aldon Music, a firm that signed young songwriters such as Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield, along with Gerry Goffin and Carole King, scarcely older than the teens who bought the records. The firm had more than one hundred songs recorded in 1961.

Independent record labels had largely captured the hit parade from staid majors such as Columbia or RCA Victor, but rock and roll, the independent label’s specialty, was losing vitality, showing signs of waning. Typical of the show business mentality that pervaded was Bobby Darin. He ditched rock and roll for big-room swing and “Mack the Knife” as soon as he could, telling interviewers that rock and roll was only for teenagers and he was an all-round entertainer. With the music business almost entirely centered in New York, conservative forces worked to marginalize this new, uncontrollable music. Under their noses, the Twist would finally demolish those barriers to rock and roll. The Twist gave rock and roll its first adult constituency.

The Twist hit like an atomic bomb, and the Peppermint Lounge was ground zero.

Grown-ups in fur coats waited in line alongside gum-chewing teenagers. Newspapers and magazines stumbled over one another covering the phenomenon. No less an authority than Newsweek reported that the Twist “a rock ’n’ roll comedy of Eros, has suddenly turned the Peppermint Lounge, a run-of-the-ginmill, into a melting pot for socialites, sailors, and salesmen.”

The Manhattan swinging set abandoned cobwebbed, old outposts such as El Morocco, Toots Shor’s, the Stork Club, and the Harwyn Club for the Peppermint Lounge. The simplicity of the dance was greatly in its favor when the adults joined in. Anyone could learn it. The Stork Club instituted Twist dancing. “I love to watch them dance,” said owner Sherman Billingsley. But the El Morocco banished actress Janet Leigh, fresh off her shocking shower murder scene in Psycho, for Twisting in her stocking feet.

One regular visitor to the Pep—as it was called—was man-about-town Ahmet Ertegun, the son of the Turkish ambassador to the United States and the founder of Atlantic Records. Ertegun rented a bus every night to ferry around his wealthy friends and hangers-on. They started with dinner at the El Morocco and invariably wound up at the Peppermint Lounge. Always a trend-setting playboy, Ertegun started frequenting the club in July 1961, ranking him among the first trickle of swells slumming with the rock and rollers. Almost overnight that fall, the little Theater District bar was turning away a thousand customers a night.

Other clubs were twisting, but the center of the Twist universe was the Peppermint Lounge, where six NYPD patrol cars were parked nightly, trying to control the crowds and cars. Fire marshals were permanently assigned. The street was so packed, crosstown traffic stopped at Broadway. Bob Hope, hosting a black tie dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria, looked over the audience that included President Kennedy, General Douglas MacArthur, and Cardinal Spellman and joked, “I have never seen so many cop cars or limousines outside. What is this—the Peppermint Lounge?”

Night after night, celebrities and socialites in furs and jewels crammed together with the teenagers in leather jackets and bouffant hairdos. The kids were a varied group, from suburban girls with their hair teased and blown to motorcycle toughs like Big Daddy, who parked his bike right in front of the club. He later owned a junkyard in Jersey where it was suspected for a time that Jimmy Hoffa was buried.

The club retained its rough-hewn style. The ham-fisted Peppermint Lounge doormen recognized and ushered in some of the celebrities—Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo. Others they didn’t recognize and denied entrance—Ethel Merman, Tennessee Williams, even Chubby Checker. When the New Yorker reporter visited, he found American Bandstand host Dick Clark standing next to dance instructor Arthur Murray and his wife, Kathryn.

There was no surer sign of the Twist’s acceptance by the broader society than the presence of Arthur Murray, the patriarch of American dance and proprietor of a nationwide chain of dance studios. “Any new dance craze will stimulate all kinds of new business,” said Kathryn Murray.

The two hosted a television program that catered to the white-gloves cotillion set, but they soon started haunting the Peppermint Lounge. “We wanted to observe the dance in its native habitat,” Murray said. “After a while even we felt the urge come across to us. And so, we got up and Twisted along with the others.”

Still, Murray didn’t think much of the Twist as dance. “No steps, pure swivel,” he sniffed. But that didn’t stop him from sitting next to the dance floor, studying every move. Within a week, the Arthur Murray Dance Studios took out a large newspaper advertisement. “Quite frankly, the Twist is not our favorite dance,” began the ad. “But, if you’re young at heart, you just have to dance it these days. It’s all the rage, and you can become a Twist expert in six easy lessons…”

When the sixty-six-year-old fuddy-duddy started coming in, Louie Lombardi was alarmed. “He looks like he’s going to drop dead any minute,” Louie said. “I told Captain Lou (one of the bouncers) to take him outside if he starts to go. I don’t want anyone dying in here.”

It was maitre d’ Joe Dana who told Louie who Murray was. “He’s here to learn all the new dances for his studios.”

“You’re kidding, right?” Louie said. “These kids dance so far from their partners, you need a search party to find them when the song’s over.” Around the Peppermint Lounge, Murray was known as a lousy tipper.

If the Murrays represented one end of the spectrum of popular American dance, Killer Joe Piro was at the other end and he, too, took up residence at the Peppermint Lounge. A former champion Jitterbugger, the athletic Piro was the master of ceremonies at the Palladium and presided over New York’s Mambo craze through the fifties. He taught New York bluebloods to dance in his West 55th Street studio, where he quickly started giving Twist lessons. Unlike Murray, Piro was an enthusiastic Twister.

Broadway, just around the corner, was not immune. Actor Phil Silvers, starring in the musical Do Re Mi at the St. James Theatre, came by the club one night and immediately whisked the Twist into the production. Three dancers did the Twist to a jukebox in the show. Hal March, star of the Broadway play Come Blow Your Horn, swapped out the Cha-Cha-Cha in one scene in the show for the Twist after a visit to the club.

Life magazine shot photos of Senator Jacob Javits with Jean Smith, President Kennedy’s sister, and Tennessee Williams, tie loosened, fingers cradling a cocktail glass.

Joey Dee and the Starliters, the house band, had been the hottest band in northern New Jersey when they landed the Peppermint Lounge job a year before and had honed the band’s act razor sharp.

Dee’s band was the hit of the society season in New York. Earl Blackwell, publisher of the Celebrity Register and a Peppermint Lounge habitué, booked the band to play a Girls Town benefit at the Four Seasons restaurant that was hosted by Eleanor Roosevelt in November. They appeared the next night at the victory celebration for Mayor Robert Wagner, played the Bourbon Ball at the Plaza Hotel and a $100-a-plate Party of the Year fund-raiser at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met’s director, James J. Rorimer, fumed when he saw “photographers hastening to photograph the guests doing the Twist at the shrine of Rembrandt and Cezanne,” wrote Gay Talese in The New York Times.

“I did not invite them,” he said. “I was not aware of this.” His wife was in the other room, getting Twist lessons.

In playing midwife to the Twist and the adult liberation of rock and roll, the Peppermint Lounge laid the blueprint for all future rock nightclubs. It may not have been the first rock-and-roll club, but it was the first famous one, the fountainhead of every rock-and-roll nightclub that would follow.

The club employed its own set of dancers, the Peppermint Twisters. The waitresses danced when they weren’t serving drinks (and sometimes when they were). In a sense, Go-Go dancing was invented at the Peppermint Lounge. One of the cute, young waitresses who offered impromptu demonstrations and casual lessons, in between carrying trays of drinks from the bar, was Janet Huffsmith, an underage girl from Pittston, Pennsylvania, who was known as Granny Peppermint because she’d used her older sister’s ID to land the job. She was an inspired Twister. “If you couldn’t shake your fanny you weren’t hired,” she explained decades later. In a moment of abandon one night, Huffsmith leaped up on the chrome railing that surrounded the dance floor and inadvertently invented rail dancing, almost immediately adopted as a signature trademark of the raucous scene. Later on, she couldn’t recall what inspired her. “I just got up there and did it,” she said.

That was really the beginning of a new kind of professional dancing—untrained, acrobatic, rock-and-roll dancing. The power of the Twist was such that Huffsmith became a celebrity herself, doing the Twist on The Ed Sullivan Show, at Carnegie Hall, and then on a tour of South America.

Within a few years, the Peppermint’s rail dancers would be transformed at French discotheques into the prototypical sixties Go-Go dancers, clad in thigh-high white boots, ponytails flying, suspended high above club stages in cages.

As the elite of New York society flocked to the dingy dive, sending out shock waves that reverberated around the world—London, Paris, Tokyo—few of the patrons of the Peppermint Lounge gave much thought to the management of the club. Ralph Saggese, a former NYPD lieutenant, thirteen years off the force, acted as the owner. His name was on the records. He was there every night and usually did the talking when the reporters came around. In his midnight blue suit and white tie, Saggese radiated the kind of genial authority expected of a nightclub owner. Only he wasn’t really the owner.

The world-famous Twisters and high-society dilettantes who converged on the West 45th Street rock-and-roll bar would have been surprised to know that the club was actually owned by a powerful figure in New York’s criminal underworld, a capo in the Genovese family, Johnny Biello. Few knew that the Peppermint Lounge had been the headquarters and hangout for Biello and his men, who operated loan sharking and gambling rackets out of the back room. Waitresses like Huffsmith never knew, either, although there was a lot of whispering when they saw “these big men” come in and huddle with Sam Kornweisser, Johnny’s man on the scene, in the back room.

Mob associations with New York nightclubs were hardly big news. Birdland, the top jazz spot on 52nd Street, was owned by Morris Levy, who also ran the Roulette Records label, fingered by the FBI as the front man for the syndicate in the record business. He and Joe (The Wop) Cataldo, another known crime figure, also operated the Roundtable, where the risqué Jewish comedienne Belle Barth was playing when they decided to convert to a Twist program. They brought in a rock-and-roll band from Memphis, Bill Black’s Combo, whose latest hit was “Twist-Her.” Keyboardist Earl Grant, booked to follow Barth into the club, suddenly found himself with a hole in his schedule.

The Peppermint was not really a major part of Biello’s business. After moving to Miami to free himself from his Mob entanglements, he had invested in a carpet plant with the hope of lying low and easing into a mellow retirement, forgetting and forgotten.

Never a murderous criminal, Biello’s fate lay balanced between shifting powers and shaky loyalties, none of which was what it seemed. He wanted to slip away quietly. Easier said than done. The son of Italian immigrants, Biello had spent his entire life on the other side of the law, having grown up with the founders of the modern Mafia, Frank Costello and Charles (Lucky) Luciano. The life was something Biello was practically born into.

Copyright © 2012 by John Johnson, Jr., Joel Selvin, and Dick Cami

The 60’s were the most influential years of my life. I have to buy this book.

I loved reading the excerpt from your book and can’t wait to download the entire book and read more……

I grew up with the Peppermint! Sam Konwiser (FYI his name was misspelled in your book!!) was my grandfather!

I would love to hear from you and share some stories!

Gail

I love reading books that have my era and places I know brought to life again. Some good, some bad, but all the way it was.

GothamGail, I noticed the same, Sam Konwiser is spelled wrong in the book. He was my Uncle and married to my Aunt Anna. Write me if you read this I would to hear from you. [url=mailto:Sgtfl@hotmail.com]Sgtfl@hotmail.com[/url] is my email.

GothamGail, I noticed the same, Sam Konwiser is spelling wrong in the book. He was my Uncle and married to my Aunt Anna. Write me if you read this, I would like to hear from you. [url=mailto:Sgtfl@hotmail.com]Sgtfl@hotmail.com[/url] is my email.

When I was a sophomore in college, three or four of us took the train to NewYork one weekend, on one night of which we had a beer at the Peppermint Lounge. I recall it being wall-to-wall people and loud music.