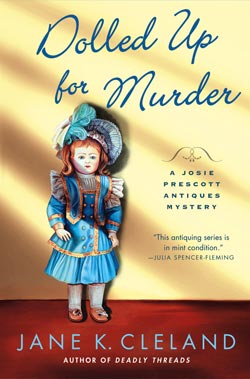

On a sparkling spring day in the cozy coastal town of Rocky Point, New Hampshire, with the lilacs in full bloom and the wisteria hanging low, antiques dealer Josie Prescott is showing a stellar doll collection she’s just acquired to Alice Michaels, the queen of the local investment community. Moments later, Josie watches in horror as Alice is shot and killed. Within hours, one of Josie’s employees, Eric, is kidnapped. The kidnapper’s ransom demand is simple—he wants the doll collection. Working against the clock with the local police chief, Josie discovers that the dolls hold secrets that will save Eric and uncover the truth behind Alice’s murder.

Chapter 1

Gretchen, administrative manager of Prescott’s Antiques & Auctions, spread the photographs over her desk. “I can’t decide,” she said. She looked up and smiled at us, her expressive green eyes reflecting her pleasure. “What do you think? Should I go with the blue hydrangeas and paperwhites? Or the veronicas and baby’s breath?” She angled the two photos so we could see them.

“I love hydrangeas!” Cara, our receptionist, said. Cara was grandmotherly in appearance, with curly white hair and a round pink face that grew pinker when she felt pleasure, embarrassment, or sadness.

“Me, too,” I said, leaning over to see the images. “Especially the blue ones—and the paperwhites in this bouquet are beautiful.” I looked at the other photo Gretchen was holding and laughed. “You’re going to hate me because I’m not going to be of any help at all. I love these veronicas, too!”

“They’re so delicate,” Cara agreed. “Really lovely.”

“I don’t know,” Gretchen said. She gathered up the photographs and jiggled them together. “Luckily I have a week before I have to decide.”

The wind chimes Gretchen had hung on the back of the front door years earlier jingled. Lenny Einsohn stepped inside.

“Josie,” he said. He nodded at Gretchen and Cara, then looked back at me. “Do you have a minute?”

Lenny looked awful, pasty white and too thin. I wasn’t surprised. Wes Smith, the incredibly plugged-in local reporter, had just broken the story that Alice D. Michaels, the founder and CEO of ADM Financial Advisers Inc., was being investigated for running a mega-Ponzi scheme, with or without her associates’ knowledge. The associate most often mentioned as the brains behind the scheme was Lenny. Alice had fired him three months earlier, at the first hint of trouble.

I knew Lenny because his oldest son, now away at college, had caught the stamp-collecting bug in junior high school, and after witnessing his elation at several tag sale finds, his parents had joined in the fun. Lenny started collecting Civil War maps and ephemera and his wife, Iris, fell in love with Clarice Cliff jugs.

“Sure. Let’s go up to my office.”

I pushed open the heavy door, stepped into the warehouse, and led the way to the spiral staircase that led to my private office on the mezzanine, our footsteps echoing in the cavernous space. I considered directing Lenny to the yellow upholstered love seat and Queen Anne wing chairs but didn’t. A little voice in my head warned me I should keep our interaction all business.

“Have a seat,” I said, sitting behind my desk as I pointed to a guest chair. “What can I do for you?”

Lenny looked as if he’d rather be at the dentist getting a root canal without anesthetic than talking to me.

“I was going through my Civil War documents the other day. I’ve acquired some nice things over the last few years. Some original maps showing forts and so on. I have two letters signed by Lincoln, too. I paid thirty-five thousand for one of them—a thank-you to Ulysses Doubleday for information about Fort Sumter.” He crossed his legs, then uncrossed them. “I’d like to sell the entire collection.”

I didn’t want any part of it. If Lenny was charged with larceny or fraud or anything related to financial improprieties at ADM Financial, the courts would freeze his assets until the case was settled one way or the other. In situations like this, the authorities often went back ninety days or even longer, trying to recoup monies for victims.

My window was open, and a stack of papers fluttered in the soft , warm breeze. I moved a paperweight—a water-smoothed gray rock my boyfriend and I had picked up from a purling brook during a hike in the White Mountains last summer—onto the top of the pile. Lenny kept his eyes on me, waiting for me to speak.

“Do you want me to appraise the collection for you?” I asked.

“No. I’m hoping you’ll buy it.”

If I purchased his collection and he was subsequently convicted, the courts might decide that the proceeds of the sale should have benefited his victims, not him. Thinking through the worst-case scenario, the powers that be might even confiscate the collection on the theory that it had been originally purchased with stolen money. I’d be out the cash I’d paid him, and the public might think I’d conspired with Lenny to snooker them. That scenario had ugly written all over it. I tried to think how I could extricate myself without offending him but couldn’t. There was no easy way out.

“Sorry, Lenny. I have to pass.”

He bit his lip and tapped the chair arm. “I’ll give you a good deal.”

I shook my head. “Sorry.” I stood up. “Let me walk you out.”

Back upstairs in my office, I picked up my accountant Pete’s good-news quarterly report, then put it down, my interest in revenue streams and profit margins waning as the breeze wafted through my window. I put the report aside and started reading my antiques appraiser Fred’s draft of catalogue copy for an auction we were planning for next fall on witchcraft memorabilia, thinking it would be more engaging than financial data, but within minutes, I found myself staring at the baby blue sky. I was suffering from a serious case of spring fever.

“Come on, Josie,” I told myself. “Concentrate.”

I reached for a media release we planned to send to doll magazines, blogs, and book reviewers announcing the purchase of Selma Farmington’s doll collection.

Selma Farmington had died just a week earlier in a horrific car accident, and now her daughters, up from Texas, were facing the daunting task of clearing out the sprawling home that had been in their family for generations. When they’d called me in to buy some of the antiques, they’d been frank about feeling shell-shocked and overwhelmed. I’d encouraged them to let me take the time to appraise the doll collection so they could sell the dolls individually at full retail, the best way to command top dollar, but they weren’t interested.

They hadn’t even wanted to consign the dolls. When I explained that in order to buy the collection outright, I had to offer them a wholesale price, they’d understood. After a brief discussion, they’d asked me to raise my offer from one-third of their mom’s carefully recorded expenditures to half, and I’d agreed. The $23,000 sales price was fair. Once the dolls were properly appraised, cleaned, and repaired, I’d be certain to make a good profit, and they had one less collection to worry about. While Selma’s doll collection wasn’t of earth-shattering quality, I thought it was varied enough to be of interest to collectors and dealers. My fingers were crossed that we’d get good media coverage. I finished reading the release, e-mailed Gretchen that it was good to go, then considered what to do next.

Nothing appealed to me. I was about to struggle through another few pages of Fred’s catalogue when Gretchen IM’d me. Alice Michaels had called for an appointment, and she’d scheduled her at three. First Lenny, now Alice, I thought. I glanced at the time display on my computer monitor. It was three minutes after two. I gave up trying to work, pushed the papers aside, and headed downstairs. I decided to walk to the church about a quarter mile down the road to the east, in the hopes that indulging my need to be outside for a little while would enable me to buckle down when I returned. Cara was on the phone giving someone directions to Saturday’s tag sale. I told Gretchen I’d be back in half an hour or so.

I stood for a moment in my parking lot enjoying feeling the sun on my face and listening to the birds chat to one another, then started down the packed dirt path that wound through the woods, a shortcut from my property to the Congregational Church of Rocky Point. Everything was blooming or in bud, filled with the promise of renewal, of hope.

May was my favorite time of year in New Hampshire. The wisteria and lilacs were in full bloom, the wisteria hanging low over lush green grass and the lilacs scenting the roads and fields. Violets and lilies of the valley dotted the forest floor. Queen Anne’s lace and heather grew in wild abandon near the sandy shore. May was idyllic. So was June when the dahlias and peonies were in bloom. September was dazzling, too, with its fiery colors and crisp evenings. As was October, with pumpkins as big as wheelbarrows proudly placed on porches and golden and cordovan colored Indian corn hung on doors. The fresh-fallen snow in January created a winter wonderland that to my eye rivaled the postcard-perfect Alpine slopes. I smiled, realizing how much I loved New Hampshire in all seasons, how fully my adopted state had become my home. I paused to admire a clutch of Boston fern, their new fronds just unfurling.

As soon as I stepped onto the church grounds, I spotted Ted Bauer, the pastor, standing by the side garden. I walked to join him.

“Hey, Ted,” I said as I approached.

He looked over his shoulder and smiled. Ted was of medium height and stout. His blond hair was graying, and he’d gained some weight over the last year or so. He looked his age, which I guessed was close to fifty.

“Hi, Josie. You caught me playing hooky. I have an acute case of spring fever.”

“Me, too. I don’t want to do anything but wander around outside admiring plants and flowers and birds.”

“I understand completely. I’ve been standing here looking at the impatiens for way too long. I should be inside preparing next Sunday’s sermon.”

“It’s only Monday. You have time. I should be reviewing catalogue copy Fred wrote. He can’t continue his work until he hears from me.”

“I wish I had plenty of time, but the truth is that it takes me all week to write a sermon. When’s the auction?”

“September. Which, despite being months away, will be here before we know it. We have to start promoting it soon.”

“We share a good work ethic, Josie.”

“That’s true,” I acknowledged.

“But you know what?” he asked, his smile lighting up his eyes. “It’s all right to take a little time now and again to appreciate things like flowers and birds.”

“I know you’re right, but I still feel guilty.”

“Me, too. How’s this? I won’t tell on you if you don’t tell on me.”

“Deal,” I said, grinning.

I circled the church and waved good-bye to Ted as I entered the pathway for my return journey. I stepped onto the asphalt outside Prescott’s in time to see Alice Michaels pull into a parking spot near the front door. I walked to join her. I felt the muscles in my upper back and neck tense as I braced for another difficult conversation.

Chapter 2

I don’t know what it is, Josie,” Alice Michaels said, gently stroking the antique doll’s feather-soft auburn hair, “but just touching this little beauty takes my mind off my troubles.”

The Bébé Bru Jne doll from Selma’s collection was a beauty, marred by a poorly repaired ragged crack on the back of her head. I tried to think how to respond to Alice’s comment. Her troubles were no longer private, that was for sure, not after Wes published all the gory details, yet I was surprised she was talking about her situation so openly. She sat across from me at the guest table in the front office where everyone could listen in. From Gretchen’s expression, I could tell that she was all ears. She loved being in the know. Maybe, I thought, Alice didn’t care what anyone thought. Or maybe she felt that she was among friends, that at Prescott’s, she’d be safe from criticism. Regardless, she looked fine, the same as always. Her dyed blond chin-length hair was newly coiffed. Her makeup was subtle and flawless. Her navy blue gabardine suit and white silk blouse fit her like a dream.

“Have you heard anything more?” I asked, hoping my tone conveyed my genuine concern, not just my curiosity.

She looked up from the doll and met my eyes. “No, but they always say the victim is the last to know, right?”

She thinks of herself as a victim, I noted, wondering if it was true. Was she being set up as a scapegoat? Was Lenny? In his article, Wes had quoted an unnamed senior official in the district attorney’s office as saying the two of them, and maybe additional employees and vendors as well, were going to be indicted within days, maybe within hours. Grim. Alice was watching me, gauging my reaction to her words. I tried to think of something kind or supportive to say.

“It’s no fun waiting for someone else to make a decision about your future.”

“Especially for a control freak like me,” she said, trying to smile. “Whatever. Instead of spinning my wheels, I’ll admire this young lady’s complexion—classic peaches and cream. What talent the makers had! Tell me about her.”

“With pleasure. How about a cup of tea? Would you like one?”

Her nose wrinkled. “Tea—awful stuff. Maudles your insides. I never go near it. I’ll take a coffee, though, if any is available.”

“Absolutely,” Gretchen said. “I’ll bring some gingersnaps, too.”

“Thanks, Gretchen.” I turned my attention back to the doll. “This doll, which is one of twenty-three that make up the Farmington collection, is a Bébé Bru Jne.” I pronounced the tongue-tangling word as a cross between June and gin. “Her coloration is typical for the style, and as I’m sure you know, nineteenth-century dolls in unused condition are as rare as all get-out. Her head is made of bisque, pink tinted and unglazed, a proprietary formula. Her wig is made of human hair, probably original to the doll. Ditto her clothes—the white underdress appears to be fine cotton. The blue overdress is probably made of silk. Once we complete the appraisal, we’ll know for certain what the materials are and whether they’re original. Both dresses are hand-stitched. Unfortunately, at some point her head got cracked and someone repaired it, not well. They didn’t use archival-quality products, and significant yellowing has occurred. The only good news is that the crack is hidden by her wig.”

“A cracked head! The poor girl. Still, I think she’s spectacular, cracked head and all. I look forward to holding her very frequently.” Alice paused and sighed. “My mother never let me play with her doll collection, did I ever tell you that? They were to be admired from afar, but never touched.” She snorted, a humorless sound. “Now here I am doing the same darn thing, building a collection to give to my granddaughter, knowing that her mother, Ms. Attila the Hun, won’t let her play with them.” She shook her head. “Funny how what goes around comes around, isn’t it?” She waved it away. “Old news is boring news—throw it out with the trash. All I can do is hope that Brooke loves the collection as much as I do—even if she won’t be allowed to play with it.”

“I bet she has other dolls, not collectibles, that she can use,” I said, hoping it was true.

“Dozens,” Alice acknowledged. She looked at me as an impish smile transformed her countenance from polished adult to mischievous child. “When I was about seven, I sewed myself a sock doll. I used cotton scraps from my mother’s quilting basket for the stuffing and for her dress. I named her Hilda, after my favorite teacher, Miss Horne. I painted Miss Horne’s face on her, too—big blue eyes and a bright red heart-shaped mouth. I even stitched brown yarn on her head for hair. I loved that doll. I loved that teacher.” She smiled wider. “When my sister saw it, she wanted one, too.” Her eyes twinkled. “I charged her a dollar.” She chuckled. “I left a little opening in one of Hilda’s seams, a hidey-hole under her dress for my diary key. My sister searched and searched for that key and never found it. Ha!” She shook her head, a rueful expression on her face. “Jeesh! That’s more than fifty years ago, Josie, and I remember it like it was yesterday. Fifty years ago. Life was simpler then, that’s for sure. All I had to worry about back then was hiding my diary from my sister.”

“Hilda wasn’t included in the collection we appraised, was she? Do you still have her?”

“You betcha! And she’s still my favorite. I didn’t include her because I know she has no value—she’s just a handmade kid’s toy.” Alice handed over the Bébé Bru Jne with a sigh. “I know you can’t say what you’ll charge for Selma’s dolls until you’ve finished the appraisal, but are you confident it’s a good investment?”

“Absolutely. While there’s no guarantee, prices on dolls have been going up steadily for years, and I have no reason to think that will change anytime soon.” I smiled at her. “I know you’re impatient, but these things take time. We’ll know more soon.”

Gretchen set a tray on the guest table. As I thanked her, Alice reached for her coffee.

“Do you think my granddaughter will like them?” she asked.

“Of course!” I said, surprised at the question. “What little girl wouldn’t?”

“I suppose.” She sounded unconvinced. “Can you guess which doll is most valuable?”

“Until the appraisal is complete, I really can’t. That said, Selma kept meticulous records, so I know how much she paid for each doll and where she purchased them. It appears that none is unique, and most of them have flaws, like that Bébé Bru Jne’s poorly repaired head. Of course, you know what a lack of scarcity and poor condition do to value.”

“I sure do.” Alice turned to assess the dolls lined up on Sasha’s desk. Sasha, my chief appraiser, was about to begin the complex appraisal. “Those are Selma’s dolls, too, right?” Alice asked, pointing at the far end of Sasha’s desk where a rugged-looking, decked-out-for-jungle-combat male doll leaned against Sasha’s monitor next to a dramatically carved and boldly painted cottonwood doll with a fierce expression. “What are they?”

“According to Selma’s inventory, this one is a second-round prototype of G.I. Joe.”

“Which I suspect is less valuable than a prototype from the first round.”

“Much. Assuming it is what I think it is, instead of being worth a quarter of a million dollars, which is what an original prototype would sell for, it’s worth about five thousand.”

She whistled softly. “That’s quite a difference. Isn’t it amazing that collectors are willing to pay that much for a doll?”

“Dolls have proven to be a solid investment over the years. By the way, as an aside, G.I. Joe has never been called a doll. G.I. Joe is an action figure.” I smiled. “When this fellow was made, he wasn’t even called G.I. Joe. Three prototypes were created: Rocky the Marine, Skip the Sailor, and Ace the Pilot.”

Alice smiled, too, a small one. “He looks like a Rocky. How about that other one? What is it?”

“It’s called a kachina. It’s native to the Hopi.” The doll’s face was hand-carved with an open mouth and bug eyes. It appeared to be half mythical beast and half bovine. Horns and feathers shot out from its head like rays of sun. Green serpentine swaths were painted across the nose and cheeks. The chest was dark red. The doll had presence, conveying drama and a sense of danger. “The dolls were created to represent and honor ancestors. The elders used them to teach younger generations about their ancestors’ spirits and to solicit their blessings.”

“It looks like you’ll be expanding my horizons, Josie. Up ’til now, I’ve limited my collection to European dolls.”

“Nothing says you have to buy the entire lot. I’ll let you cherry-pick.”

“Thanks, Josie! That’s sweet of you, but I want the whole kit and caboodle. Who knows which ones my granddaughter will fall in love with. For all I know, it might be that kachina. Just because I prefer traditional dolls, traditional, that is, to me, doesn’t mean she will.” She sighed, maybe thinking of her granddaughter. “How much is it worth, do you think?”

“Not so much. It’s about a hundred years old, but only kachinas that are three hundred years old, or older, have significant value. Kachinas from the seventeenth century in fine condition go for nearly three hundred thousand dollars. I expect that this one will sell for around a thousand.”

“The differential is astonishing.”

“Supply and demand.”

She kept her eyes on the dolls. “Poor Selma,” she said. “Did you ever meet her?”

“No. I just met her daughters this week for the first time.”

She nodded. “That’s how I knew to contact you. I asked about buying the collection directly from them. They told me they sold you the dolls. Smart girls, I told them. Josie’s the best. I’m just as glad, to tell you the truth. I hate doing business with heirs.”

“It can be challenging . . . all that emotion. Jamie and Lorna seem to be having a tough time deciding what to keep and what to sell, and who can blame them? Clearing out a house is difficult enough under any circumstances. It’s extra hard when your mom’s only been dead a week and everywhere you look you see memories.”

“Especially when she dies so suddenly. Drunk drivers . . . they make me so mad I could spit.”

“Me, too,” I agreed. “It’s got to be extra challenging for them so far from their own homes. They need to get everything settled this week so they can get back to Houston.”

Alice shook her head. “It’s a terrible situation no matter how you cut it. So the girls called you in and now they’re having a hard time deciding what to sell. I bet Lorna’s the holdup, isn’t she? She’s a weeping-willow sentimentalist. Jamie’s no waffler, that’s for sure.”

I laughed. “In your job, I guess you have to be able to read people in nothing flat, right?” I said, using the trick my dad had taught me back when I was in junior high school and found myself scrunched between a gossipy rock named Cheryl and a tattletaling hard place named Lynn. Never gossip, he warned me. When in doubt, talk about process, not content.

“In less than nothing flat,” she said. “So what did they decide?”

“To sell a collection of cobalt glassware that had been packed away in the attic forever and some old wooden tools, you know, planes and levels and the like. The tools belonged to their grandfather who dabbled in carpentry, and just as with the glassware, they feel no emotional connection to them. An old collection of teapots, too, nothing rare.”

“I know those teapots. They’re ugly, if you ask me. I never understood why Selma liked them. That’s why they make chocolate and vanilla ice cream, right? Who knows why any of us like anything in particular. One of the mysteries of life.” She shrugged. “And the girls sold you the dolls?”

“Most of them,” I repeated, nodding. “There are some they’re holding back, sentimental favorites, they said, like your Hilda.”

“Good for them. What do you think, Josie? Shall I give you a check now?”

Let’s wait until we know how much we’re talking about before we do anything,” I said, wanting to avoid agreeing to a deal that might soon be voided by a court.

“Sounds reasonable,” she said.

Eric, my facilities manager, stepped into the office from the warehouse. In his mid-twenties, he still looked and carried himself like a teenager; he was tall and gangly and reed thin. Eric had worked for me since I opened Prescott’s Antiques and Auctions seven years earlier, part-time while he was still in high school, then full-time as soon as he graduated. He was conscientious and dedicated, sometimes too much so, treating even the most routine or mundane task as if it were his top priority.

“I just unloaded those rocking horses,” Eric told me, after saying hello to Alice, referring to a set of three I’d just bought from some empty nesters looking to downsize. “I’ll head to the Farmingtons’ now.”

“Great. Bring plenty of newsprint for the glassware and tools, and wrap each doll in flannel, okay?”

“And I’ll cushion everything in peanuts.”

“Eric!” Gretchen called as he turned to go. “I wanted to let you know that Hank loved Grace’s catnip heart.”

He flashed an awkward smile. “I’ll tell Grace.”

Gretchen giggled as Eric, obviously embarrassed, slipped away.

“What’s that about?” Alice asked.

“Grace is Eric’s girlfriend,” Gretchen explained. “Hank is our cat. Grace made Hank a big, heart-shaped, burlap toy, filled with catnip. With a feather.” She laughed. “Eric is a complete dog person, or he used to be.” She turned to me. “You should have seen him tossing the heart to Hank this morning and chattering away as if Hank and he were old friends.”

“Eric?” I asked in mock amazement.

“I know!” Gretchen said. “It must be Grace’s influence.”

“Combined with Hank’s charm,” I agreed. I turned to Alice. “Hank’s a lover-boy, a real sweetheart.”

“Nice—but can we veer back to the central issue?” Alice asked. “My radar is beeping. Did I hear Eric say he was going for more of the Farmington dolls?”

I smiled. “Yup! I only had enough packing material to bring back the teapots and eleven dolls this morning. Eric will get the rest now, along with the other collections I bought—the glassware and tools.”

“I don’t know how you do it, Josie. Glassware . . . teapots . . . tools . . . you seem to know everything about everything.”

I laughed. “Hardly! I just know the questions to ask and have secret weapons in the form of Sasha and Fred, my appraisers.”

“Modest as ever.” She turned to Gretchen. “Your big day is close, I hear.”

“Three weeks, five days, and three hours—but who’s counting!”

Alice calculated for two seconds. “That’s June fifteenth, around six thirty. I love June weddings!”

“Me, too,” Gretchen said, giggling. “It’s going to be fabulous—homey and intimate—about fifty people in my fiancé’s folks’ backyard up in Maine.”

“They toyed with eloping to Hawaii,” I remarked, “and robbing all of us who love them the opportunity to witness their marriage.”

“A thousand years ago, I eloped,” Alice said. “Not to a beach, cry shame, just to City Hall. Back then, girls who got pregnant got married pronto.” She shook her head as if she were shaking off a bad memory. “I don’t recommend it, but it’s probably better than those pretentious megaweddings, all staged pomp and no personality. Better to be with people you love, and no one else. Fifty people sounds about right.”

The chimes sounded as Sasha stepped inside.

As soon as she saw Alice, she said, “Sorry,” her voice barely audible, as if she’d intruded into a private conversation and expected to be chastised.

“No problem,” I said, just for something to say.

Sasha’s manner changed as abruptly as if a switch had been flipped the second she spotted the eleven dolls lined up on her desk. Place an antique in Sasha’s orbit and she was transformed from scared mouse into confident expert.

“Wow!” Sasha said. “Are these from the Farmington collection? They’re gorgeous!”

“Eric just left to get the rest.”

“I’m buying them all from Prescott’s,” Alice said.

“Which means that appraising them is your new top priority,” I told Sasha.

“Okay,” Sasha said with a quick smile. She tucked a strand of lank hair behind her ear.

“So where do you start?” Alice asked her.

“By authenticating and valuing each doll.” Sasha picked up a character doll, another Bru. “She’s spectacular, isn’t she?”

“Well, I look forward to calling them my own. Right now, though, I’ve got to mosey. I’m off to my lawyer’s office, no doubt to hear more bad news. Are you sure you don’t want some earnest money to guarantee that I get first dibs? I don’t want someone else to swoop in while I’m not looking.”

I laughed. “You collectors! There’s no need.”

“I insist,” she said. “I’ll sleep better if I leave a deposit. How about if we label it a refundable right of first refusal, so if there’s some problem with provenance or you discover one of the dolls had been owned by Queen Victoria, or something equally lofty, you’re not on the hook for any certain price, or even to sell it at all, and if I change my mind for what ever reason, I’m not committed to buy something I no longer want.”

I thought about it for a few seconds. Until I knew which way the prosecutorial wind was blowing, I didn’t want to commit to selling her the dolls even with a we’ll-figure-it-out-later price, and this seemed to be a face-saving, nonconfrontational way to achieve that objective.

“Done!” I said.

She pulled a brown leather checkbook folder from her purse and sat at the round guest table to write out the check. I asked Gretchen to prepare a receipt. The second Gretchen’s eyes were fixed on her computer monitor, I turned to Cara, caught her attention, and winked.

“I have an errand,” I said and winked again. “I’ll be back in about an hour.”

Cara, her blue eyes twinkling, winked back. She knew what I was up to—I wanted to find some Hawaiian-themed goodies for Gretchen’s surprise bridal shower. I had ten days, but I didn’t know how much trouble I was going to have finding what I had in mind, so I wanted to check out the local party store pronto.

“Thanks,” Alice told Gretchen as she accepted the receipt, tucking it in her purse without even glancing at it. “Now I have bragging rights.”

The wind chimes sounded. A tall green bean of a man with a mane of sandy brown hair and earnest brown eyes walked in. I knew him by sight; everyone did. He was Pennington Moreau, the intrepid adventurer, award-winning athlete, and on-air legal personality for Rocky Point’s TV station, WXFS.

Penn, as he was known, was as well regarded for his record-setting, multimillion-dollar, long-distance balloon rides, iron man triathlon wins, and high-stakes poker games as he was for his illuminating commentary. Penn had a gift for translating complex legal issues into common English, using engaging examples and self-deprecating humor. He used his twice-weekly two-minute segments to explain things like the city’s responsibility to repair beach erosion after a brutal nor’easter (“Where people like me keep rebuilding, an example of hope trumping experience”); how a restaurant dishwasher had used his computer skills to set up shop selling fake IDs (“Using computer skills so sophisticated, it makes you wonder why he stayed washing dishes”); the government’s right to regulate gambling in private homes (“Like last month’s poker game where I lost my shirt”); and the long-term impact on building the new high school if voters turned down the proposed bond issue (“Ultimately, lower property values, even for those of us who keep adding real property by trucking in tons of sand to counteract the effects of beach erosion”). Although he had to be in his late forties, his loose-limbed gait, full head of hair, and unlined face made him appear younger.

“What on earth are you doing here, Penn?” Alice asked, leaning in for a butterfly kiss.

He kissed Alice’s cheek. “I’m looking for you, gorgeous! Got a sec?”

“For you? Of course. Anytime.” Alice pointed to the dolls on Sasha’s desk. “Look what I just bought! Twenty-three beauties.”

“Nice! Are they rare?”

“Rare enough,” she said proudly.

“I like your style, Alice. Always have.”

She smiled. “Do you know Josie?” she asked him, and when he said he hadn’t had the pleasure, she introduced us.

“I enjoy your reports,” I told him.

“Thanks,” he said, grinning broadly. “Can I steal Alice for a sec?”

“We’re done anyway,” she said. She waved around the office. “ ’Bye, all!”

Penn held the door for her, and she followed him out into the warm afternoon. Glancing at the thermometer fastened to the outside of the big window overlooking the parking lot, I saw it was seventy-five degrees, a glorious May day. I watched them walk to the center of the lot and stop. Penn said something, opening his arms and flipping his palms up—I have no choice, the gesture communicated. Alice shook her head, no, no. He spoke again, grasping her upper arms and shaking her a little, then dropping his hands and waiting for her reply. She looked away, toward the stone wall across the road, then smoothed her hair, though not one strand was out of place. She inhaled so deeply I could see her chest move. She pulled her shoulders back and raised her chin as she said something, pride stiffening her spine, it seemed. She reached a hand out to touch his arm, an appeal. He shook his head, brushed her arm aside, and strode off to his car, a cream-colored vintage Jaguar. She stood and watched. Poor Alice, I thought.

I said good-bye to everyone in the office and stepped outside. Penn was just pulling out of the lot, turning right, east, toward the church, toward the ocean. Alice watched him until his car was out of sight, then turned to face me. We stood, the silence lingering awkwardly between us. A muscle twitched in her neck. I guessed Penn had been the bearer of more bad news. If I were her, I wouldn’t want to talk about it, at least not with a relative stranger like me.

“Bye-bye,” I said aiming for a light tone. “I’ll let you know when the appraisal’s done.” I turned away and hurried toward the last row of the parking lot, where I’d parked.

“Penn didn’t want to blindside me,” she said in a brittle monotone.

I stopped and looked at her. Her eyes burned into mine. Earlier she’d sounded philosophical. Now she sounded angry.

“He said he came to tell me in person because we’re friends. Ha. Some friend. His segment tonight will explain what my impending indictment for fraud means to the alleged victims, and whether they have any recourse against me personally. They’re giving him double time. Four whole minutes.”

“Oh, Alice,” I said. “I’m so sorry.”

“Don’t you agree it was thoughtful of him to come?” she asked sarcastically. “He didn’t want to tell me on the phone, but he wanted me to know. So considerate! He even went to the trouble of tracking me down. Not so much trouble, of course. All he had to do was call my office. My assistant told him where he could find me. Still, he didn’t have to do it. Penn’s a peach, all right. A real peach. Damn him. Damn his eyes.”

“Isn’t there anything you can do to stop him?”

“No. He said he has a source at the attorney general’s office. Apparently I’m about to be arrest—.” She broke off as a crack reverberated nearby. “What was that?”

I recognized the sound. Gunfire. Someone was shooting at us.

“It’s a gun!” I shouted as I dropped to the ground. “Get down, Alice!”

Another loud, sharp clap shattered the quiet. Then another. Think, I told myself. Where are the shots coming from? I knew that sound traveled and reverberated and bounced off solid objects, making it hard to trace under the best of circumstances and probably impossible now, but concentrating on finding the shooter was all I could do to try to save us. I peered into the closest slice of forest and saw only pines and brambles and forsythia bushes swaying in the light breeze. More shots were fired. I scooted to the front of my car and looked across the street, past the stone wall, into the dense growth that stretched from the road to the interstate almost a mile to the north. No glint of silver or unexpected movement caught my eye. I crawled around my car until the dirt path that led to the church came into view. Nothing. I looked back at Alice. She hadn’t moved. She looked half shocked and half confused, as if she simply couldn’t process what was happening.

“Get down!” I yelled again, patting the air for emphasis.

She didn’t move. She wasn’t looking at me, and I wasn’t certain she heard me. It was as if she were a million miles away, frozen in some private memory.

“Alice!” I hollered as another shot rang out. “Get down! Duck!”

She grimaced and grunted. She rocked forward, falling against her car as she uttered a low guttural groan. As splotches of red spread over her chest and stomach, her eyes found mine, and she sank to the ground.

Copyright © 2012 by Jane K. Cleland.

Jane K. Cleland once owned a New Hampshire-based antiques and rare books business and now lives in New York City. An Anthony Award and two-time Agatha Award finalist, she is a board member of the New York chapter of the Mystery Writers of America and chair of the Wolfe Pack’s literary awards.