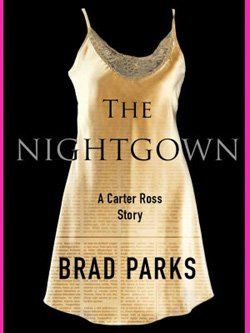

An exclusive short story, The Nightgown by Brad Parks, featuring Carter Ross, is now available on Criminal Element for members.

An exclusive short story, The Nightgown by Brad Parks, featuring Carter Ross, is now available on Criminal Element for members.

Only 24 years old and still a wide-eyed reporter for a tiny backwater newspaper, Carter Ross is getting his crack at the big leagues with an interview at New Jersey’s largest paper, The Eagle-Examiner. If—that is—he nails the interview and the on-the-spot writing test. Ross has never had a problem spinning a story, but provided with notes he didn’t take and quotes he didn’t hear it feels flat, and he’s not so sure about his chances. So when a car crashes into a building in a nearby town and Carter overhears the assignments editor complaining that there’s no one left in the building whom she can send out to cover the story, Carter jumps at the chance and quickly finds himself dangerously close to being in over his head.

The Nightgown

A Carter Ross Short Story

When ranking life’s more pointless exercises—and I’m including things like ironing your underwear, flossing your dog and watching daytime television—the newspaper writing test deserves special consideration.

It is a time-honored and ritualized form of journalistic hazing wherein a job applicant, after a day of meeting with editors in glass offices, is made to write a fake story on fake deadline. They sit you down with a pile of notes (which you did not actually take), quotes (which you did not actually hear) and color (which you did not actually see) and expect you to produce an article about some imaginary homicide/city council meeting/girl scout jamboree—and craft every sentence as if your future depended on its brilliance.

The idea, of course, is to simulate what the candidate would do with an actual story on an actual deadline. The only problem is it doesn’t really simulate anything—besides, perhaps, how well you take writing tests.

Any journalist worth his ink understands great writing begins with great reporting: the keen eye for detail, the ability to ask the right question at the right moment, the mental horsepower to quickly absorb new information, the narrative instincts to understand what’s pertinent and what isn’t. Writing a story with someone else’s notes is a bit like baking a cake with someone else’s batter.

Nevertheless, there I was, with several sheets of gooey slop in front of me, making like Betty Crocker.

I was interviewing for a staff writer position at the Newark Eagle-Examiner, New Jersey’s largest and most respected news-disseminating organization. This was eight years ago, back when newspapers were still hiring and I was a young cub of 24. Up to that point in my life, the largest newspaper to carry the byline “Carter Ross” was a 40,000-circulation daily out in the hinterlands of Pennsylvania.

Merely walking into the doors of the Eagle-Examiner—whose circulation was roughly ten times as large—was a huge deal for me, especially since I’m a New Jersey native who grew up reading it. Plus, as an ambitious sort of fellow, it was either a perfect steppingstone to something bigger or, even if it never took me anywhere, a pretty good place to end up.

I had managed to get its editors’ attention with some of my recent work, most notably a series of stories that came about when I uncovered a small-town pastor who was inventing imaginary winners to his church’s 50-50 raffle so he could keep all the proceeds for himself.

He got indicted. I got a job interview.

That’s the way it works in journalism, where stars are often made on the stupidity of others. (Even my hero, Bob Woodward, would today be a talented-though-little-remembered reporter for The Washington Post if the Committee to Re-elect the President was any good at breaking and entering).

So, thanks largely to one greedy minister, I found myself in the Eagle-Examiner newsroom, slogging through a writing test. I was trying to take it seriously, inasmuch as it could help change my career trajectory. But I also kept hearing a running dialogue between Assistant Managing Editor Sal Szanto—the guy who would most likely be deciding whether I got hired—and a woman on the night desk. She seemed to be some kind of lesser assignment editor but what I noticed most is that she was a knockout: an attractive, long-limbed, curly haired brunette. She was almost certainly on the other side of 30, a few years older than me, but that didn’t strike me as a big deal—legs like that tend to discourage any thoughts of age discrimination.

From what bits of conversation I heard, I could sense she was growing agitated about something. I just couldn’t tell what. There was news breaking, that much was clear. Someone important had done something of interest and Szanto wanted a reporter dispatched to chase it down.

And, apparently, at 6:30 at night, they didn’t have an extra warm body. As I began eavesdropping more assiduously, I heard the brunette say, “… can’t send Petersen. The last time he left the office we were still using hot type. Besides, he’s doing rewrite tonight.”

“What about Hays?” Szanto asked.

“He left twenty minutes ago, which probably means he’s drunk already.”

“Whitlow?”

“Vacation,” the brunette informed him.

“And there’s seriously no one in the Union County bureau who can hop on this thing? Come on, we’ve got to have someone,” said Szanto, signaling his concern by throwing down a handful of Tums and crunching noisily on them.

As I rose from my chair and walked toward them, I heard the woman protest, “I know, but what am I supposed to do, pull a reporter out of my…”

“I’ll go,” I interrupted.

The woman studied me like I had just fallen out of the Dummy Tree.

“I’m sorry, who the hell are you?” she asked.

“This is Carter Ross,” Szanto said. “He’s a reporter with the Pitts County Patriot. He’s interviewing for Millstein’s old job.”

“Nice to meet you,” I said, extending my right hand toward the woman and flashing the smile I usually reserved for bar pickups. “What’s your name?”

“Tina Thompson. But unlike you, I actually work here.”

“And I don’t. Yet. But there’s no reason to hold it against me.”

“If you’re here for a job interview, shouldn’t you be, I don’t know, interviewing with someone?” Tina asked.

“I’m just over there doing some fake writing. Why don’t I do some real writing instead?”

Szanto, who had turned his mouthful of antacid into fine chalk, kept swiveling his attention between the two of us, then turned back his office.

“What the hell,” he said as he passed through the door. “Give the kid a chance.”

Tina was fixing me with a look that registered a 9.75 on the Incredulity Scale, which normally only goes to 8.

“One of these days, I want to know what it’s like to work for a real newspaper,” she grumbled.

I once again gave her my best barstool smile.

“Oh fine,” she said. “That little rag in Pennsylvania give you a laptop and a cell phone?”

“Yeah.”

“You got them with you?”

“Always,” I said, giving her my number.

“Good. Get in your car and start driving toward Carteret. I’ll call you on the way.”

Having grown up just a few towns away from Newark, in a McMansion-intensive suburb called Millburn, I knew the way to Carteret, even if it wasn’t the kind of place where my prep school took regular field trips. Carteret was part of New Jersey’s rust belt, that corridor north of Exit 12 on the Turnpike that the state tourism commission forever wished could be moved somewhere less visible. Like Pakistan.

I had barely settled into my car, an aging Chevy Nova with brakes that could almost stop a 10-speed bicycle, when my phone rang.

“Carter Ross,” I said.

“You already sound too smug,” Tina informed me. “This is a job interview, remember? You should sound deferential and nervous.”

“You mean like: C-C—C-Carter R-R-Ross?”

“Better. Okay, here’s the deal, someone crashed his car into a building at the corner of Roosevelt and Jefferson in Carteret. Ordinarily, that wouldn’t be a big deal, except we’re hearing the someone was Lenny Ryan. You know who Lenny Ryan is?”

“Not really.”

“He’s a State Senator, but he’s more than that. Lenny Ryan has the entire Democratic portion of Union County trapped under his thumb. All the patronage hires, all the municipal contracts, all the political appointments, they all go through Lenny one way or another. And Lenny always gets his piece.”

“Sounds like a real charmer,” I said.

“He is, actually. He’s a classic Irish politician. He’s smart, charismatic, great in front of a crowd and smooth as a baby’s ass. A few years ago, we put one of our best investigative reporters on him for three months. We were going for Lenny’s scalp, but we didn’t even touch a hair on his head. We ended up running this 3,000-word puff piece on him. He’s got it hanging in his office like a trophy, from what I’m told.”

I was speeding down Broad Street in Newark by this point, slaloming between lanes. Yeah, I had spent my last two years in Pennsylvania, but it hadn’t taken the Jersey out of my driving.

“So the fact that he’s hit a building means…?”

“Maybe nothing, maybe everything,” Tina said. “I mean, was he drunk? Was he high? Was he speeding? You just have to keep in mind this guy is a major player in this state. Anything he does is news.”

“What if it was just an ordinary accident?”

“Then it’s not very interesting news, but it’s still news,” Tina said. She furnished me with directions to the location of the crash, finishing with, “If you get anything good, call me immediately.”

I drove south on the Turnpike, through the more aromatic sections of Elizabeth and Linden, until I reached exit 12. I wound around on Roosevelt Avenue, through commercial and residential areas and into an industrial stretch. Just past a trucking depot, I found what I was looking for: a brick building with a noticeable chunk taken out of its corner and a variety of lesser car parts still strewn around it.

It took me a moment to take it in, but when I did, I nearly hopped out of my Nova and did a victory jig—which is saying a lot, given that my pasty Northern European lineage is not known for its dancing skills. I pulled out my phone and dialed the last number that called me.

“Examiner, this is Tina,” I heard.

“Tina, it’s Carter Ross. I know this may sound presumptuous, because I don’t even work for you, but you may want to reserve a spot for me on the front page.”

“Why?”

“Because, the building at the corner of Roosevelt and Jefferson is not just a building,” I said, giving a quick pause before I delivered the punch-line:

“It’s a go-go bar.”

Tina quickly concurred that a powerful State Senator careening into an establishment that offered exotic entertainment—it was called Roxy’s Go-Go, if that wasn’t perfect enough—had significant news potential.

I terminated the call and began trying to figure out what happened. This, however, did not prove as simple as I hoped. The manager of Roxy’s Go-Go was inexplicably publicity shy, a member of the “we don’t want no trouble” school of media relations. He wouldn’t even give me his name, perhaps sensing that if he was seen as too forthcoming about the Senator’s mishap he would suddenly be visited by a very dogged health department inspector.

All I could cajole out of him was that around 5 o’clock he heard a loud noise and felt the building shake. He went outside, saw the car—a black Lexus—crumpled against the building. And he called the cops.

Since that was his first call, I figured it should be mine as well. I got bounced around until I ended up talking with the Police Director, who was about as forthcoming as the manager had been. Yes, he could confirm there had been a single car accident at 5 p.m. at the corner of Roosevelt and Jefferson. Yes, the car in question was registered to Leonard R. Ryan of Clark. No, he wasn’t saying anything else.

His official excuse for reticence was that it was a “pending investigation” but I knew the unofficial reason was that he wasn’t born stupid. He knew the score: The Carteret Police Director served at the pleasure of the mayor, who owed his position to the support of the Carteret Democratic Party. The Carteret Democrats, meanwhile, leaned heavily on the Union County Democratic Party, which was essentially a cult of Lenny Ryan’s personality. So while Lenny may not have been very good at controlling the steering wheel of his Lexus, he was quite adept at controlling everything else in a town like Carteret.

Hence, I was being stymied by Lenny Ryan’s perceived power. And I was starting to run out of time. It was already 7:15. I didn’t know the Eagle-Examiner’s deadlines, but as a rule the larger the paper, the earlier you needed to have copy in for first edition.

Just to have something to feed Tina, I pulled out my pad and started taking note of the detritus left scattered about the corner of the building by Lenny Ryan’s automobile—a piece of headlight covering, shattered bits of glass, some green viscous liquid. I was concentrating on a piece of random metal, which I decided I would call an L-bracket, when a tow truck with “Walter’s Auto Body” painted on the side slowed to a halt in the street.

The driver rolled down his window and hollered, “Hey, you with the insurance company? I got that car in my lot, if you want to take a look at it.”

It briefly occurred to me to say, Yes, I’m with State Farm, tell me everything. Except, of course, if the bosses at The Eagle-Examiner heard I had done it, they’d fire me before they even hired me: it’s unethical for reporters to misidentify themselves. So I trotted over to his truck and said, “Actually, I’m here doing a story for The Eagle-Examiner. Mind if I have a look at the car, anyway?”

“Yeah, I guess,” he said, then gestured to the other side of the street. “It’s right over there. You can see it from here.”

Sure enough, across the street and mid-way down the block, I could see Walter’s Auto Body. And there, hiding in plain sight, was a black Lexus with a seriously mangled front end. I could see the crease where building had met car. The front bumper was nowhere to be seen. The hood was crumpled about halfway up. The windshield no longer existed. It was clear that while a little bit of the energy of the collision had gone into knocking out a chunk of the go-go bar, most of it had transferred into the car.

“Is it totaled?” I asked.

“Don’t know yet. Takes a lot to total a new Lexus. But I don’t even know if I’m working on the thing. The police called and asked me to tow it. I haven’t heard from the owner.”

Which meant it was possible the tow truck driver didn’t know who the owner was. That was a break for me, to finally get a source who wouldn’t be worried about angering the mighty Lenny Ryan.

“Did you see the accident?” I asked.

“No, but I heard it. It was loud. I thought a truck dropped a load or something. It was a nasty hit. I just hope whoever was driving it is okay.”

I collected the guy’s name and tried to pump some other information out of him, but he didn’t have much for me.

“Did you see the driver?” I asked.

“No, just the ambulance. It got here pretty quick and carted the guy off.”

“Where would an ambulance around here take someone?”

“It was from Carteret Rescue Squad. Unless you tell ‘em otherwise, they take you to Robert Wood Johnson.”

I would probably have to call Robert Wood Johnson but, as a rule, hospitals are worthless to reporters. Ever since the invention of this infernal thing called HIPAA—the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which includes privacy regulations that are the absolute bane of the Fourth Estate—hospitals had become virtual black holes of information: nothing, not even light itself, escapes.

As such, I knew what little time I had left would be wasted there. No, given the apparent reluctance of secondary sources, I had to go to the home of the man himself. Maybe he had been treated and released. Maybe there would be a relative who could tell me what happened. Maybe a concerned neighbor would be dropping off a casserole. Something.

I phoned Tina en route to Clark, exchanging what shreds of information I had gotten for an address and directions to the domicile of Leonard R. Ryan. When I arrived at his nicely appointed home—two stories, three garages—and knocked on the door, I was surprised to see it opened by a tall, smiling, silver-haired gentleman.

“May I help you?” he said, calmly.

“Good evening, Senator,” I said, taking an educated guess this was the man himself and not his twin brother. “I’m Carter Ross. I’m doing a story for The Eagle-Examiner about your accident.”

The Senator smiled pleasantly and, without a hitch, replied, “I think it’s best I not comment. Let’s leave it to the police.”

He wasn’t drunk—or, if he had been at 5 o’clock, he had sobered up in a hurry. He wasn’t high, either. He was as unruffled as if he had just come away from a day at the spa.

“With all due respect, Senator, the police know who you are,” I said. “They don’t want to risk saying the wrong thing, so they’re not saying anything.”

He smiled again. “Well, far be it from me to second guess the police. You’ll have to put me down as a no comment. Now, if you’ll excuse me, tonight is my anniversary and my wife and I are getting ready to go out to dinner.”

Lenny Ryan gripped the door and began pushing it in the direction of my face, which I wasn’t about to let happen. I couldn’t walk away from this encounter with nothing. Sal Szanto would send me packing to Pitts County with an encouraging word about how I should reapply for a job in five years, when I had a bit more seasoning. With all due respect to the fine people of Pitts County, I’d rather eat nails.

So I stuck my foot in the door.

“Look, Senator,” I said. “Here’s how this works. I have only so much time between now and when I need to start writing this thing. Either I fill that time talking to you, or I go back to Roxy’s and keep showing your picture to the dancers until one of them has some faint inkling that she may recognize you from somewhere. Then I call you, ‘Senator Ryan, described by a dancer as a frequent visitor to Roxy’s’ with every chance I get.”

I’ll give Lenny Ryan credit: his tell was very small. Just a brief grinding of his teeth. I was bluffing like hell—that go-go-bar manager wasn’t going to let me within fifty feet of his dancers—but Lenny didn’t know that. I had him.

“Young man, are you threatening me?” he said quietly.

“Senator, I would never threaten anyone. It’s unethical. But as a reporter playing fair, I feel I have an obligation to tell you what might be written about you in the paper. Don’t worry, I’ll call you to get your response. Maybe I’ll even ask Mrs. Ryan for her thoughts here on her anniversary night—for journalistic balance and all.”

He coughed gently into his right hand, then rubbed his neck for a moment.

“Well, I always do pride myself on being cooperative with the media,” he said. “So. Very well.”

He coughed again, then continued: “I was trying to drive while handling a constituent matter—finding an out-of-work father of three a job, if you must know—and I’m afraid I took my eyes off the road. The next thing I knew my car jumped the curb and crashed into the building. That the building was a gentleman’s club was, I assure you, a coincidence. I’ve never been there before. I’m just thankful no one inside was hurt. As an elected official, I ought to be held to a higher standard, and I’m afraid I set a very bad example. I’m embarrassed by my actions, and I’m going to ask the police to cite me for reckless driving. Then I’m going to plead guilty and pay my fine.”

He began closing the door again.

“Now,” he said. “I believe that’s more than enough mea culpa for you to write your story. And I’ll be sure to tell my good friend Harold Brodie the next time I see him that you’re a very determined young reporter.”

Harold Brodie was The Eagle-Examiner’s legendary executive editor. Ryan was returning my threat with one of his own: If I pushed too hard, he’d complain to Brodie. I got the hint.

“Thank you, Senator,” I said as the door closed. “Sorry for your accident. Try to enjoy the rest of your evening.”

I was sure as heck going to enjoy mine. I had stared down one of the state’s most powerful politicians and gotten him to admit to reckless driving. It would make for a good story, one that would show the editors at The Eagle-Examiner I had some serious reporting chops.

Still, something about it wasn’t quite right. One of the toughest things as a reporter is taking the known facts and intuiting what should be there, but isn’t. If you can figure it out, it’ll often point you to a flaw in your story that you otherwise couldn’t see. As I hit the sidewalk in front of the house, the flaw finally occurred to me:

Lenny Ryan had just been in a major car crash. And he didn’t have a scratch on him.

I climbed into my Nova, pointed it back in the direction of Carteret and called Tina, feeding her the Senator’s verbal self-immolation.

“Thanks, Carter,” she said when I was done. “This is terrific, really terrific. I appreciate your help. I’ve got some extra bodies in for the night shift now. We can take it from here.”

“No you can’t,” I said. “I’m not done yet. I’ll call you later with more.”

I hung up before she could dispute me. In later years, ignoring the wishes of editors—Tina, in particular—would become a fairly routine part of my life. Back then it still felt a little dangerous, especially when I was trying to convince the paper I was worth hiring.

But this wasn’t just about getting a job anymore. This was about getting a story. And there was some part of me, perhaps written in a series of A’s C’s G’s and T’s in every one of my cells, that felt compelled to figure out what it was.

It wasn’t at the hospital. That was for sure. And at this point I had a better chance of finding Sasquatch at a tanning salon than finding eyewitnesses. If anyone had seen it firsthand—and it’s not like there were a lot of pedestrians in that part of town—they’d be long gone.

That left me with one unturned stone: the Carteret Rescue Squad.

I pulled off the road just long enough to scam wireless—God Bless people who use Lynksis routers without password protection—and ascertain the Carteret Rescue Squad was housed on Leick Avenue. According to Google maps, it was near Goumba Johnny’s restaurant and something called Yeshiva Gedola. Say what you will about New Jersey, but if there’s strength in diversity, we could beat the snot out of anyone. Especially Pitts County, Pennsylvania.

The rescue squad’s headquarters was an unassuming white rectangular building with a large bay garage and room for two ambulances. It being a nice spring evening, one of the bays was open, which any good journalist takes as a standing invitation to enter.

“Can I help you?” I heard a female voice inquire.

I turned to see three people—two guys and a woman—seated around a small folding table, holding playing cards.

“Hey, sorry to bother you,” I said. “I’m doing a story for The Eagle-Examiner about the man you took to Robert Wood Johnson earlier tonight? The guy who crashed his Lexus into the go-go bar?”

I purposefully didn’t say the name “Lenny Ryan” in case they were somehow unaware they had been carting a VIP. But I was treated to the same Dummy Tree look Tina had given me earlier in the night.

Finally the woman said, “We didn’t take a guy to Robert Wood Johnson.”

“You didn’t?” I said, wondering if I got the hospital wrong.

“No,” she replied. “We took a woman.”

I tried not to smile. I may or may not have succeeded. “A woman?” I asked. “You mean the driver wasn’t a distinguished-looked silver-haired gentleman?”

“No, it wasn’t that creep Lenny Ryan, if that’s what you’re asking,” she said. “Lenny Ryan wasn’t even there. The driver was a… how do I put it…”

She was struggling for the right words. The second guy, who hadn’t spoken yet, helped her: “It was one of the dancers.”

Now I was really having a hard time holding back my smile. Not only had I caught the righteous Senator Ryan in an outrageous lie, I had caught him with what appeared to be a stripper for a girlfriend.

“She got a name?” I asked.

“Come on, you know we can’t tell you that,” the woman said.

“But you took her to Robert Wood Johnson?”

“Sure did,” the woman said. “You can’t use our names in your story, though. We’d get in trouble.”

“Tell you what: you give me the name of the dancer, and I’ll get the whole story from her. I’d never have to mention you guys.”

The three EMT’s exchanged glances, struggling momentarily with their collective consciences, then the woman said: “Lenny Ryan has let our funding get cut three years in a row. Screw him.”

That was how I left the Carteret Rescue Squad a short time later armed with the name Jessica Martin. I knew I couldn’t use it in the newspaper yet—not without better sourcing—but I could at least use it to find her.

And the first place to look was Robert Wood Johnson Hospital. It was true that hospitals couldn’t tell you squat anymore, but there was no gag order on their family or friends, the kind of people who just might be hanging around the emergency waiting room.

I started my search outside, where a few nicotine addicts were sating their cravings, asking each person, “Excuse me, are you here for Jessica Martin?”

Then I moved inside, working slowly around the large, crowded room. If a hospital PR person got wind I was working the waiting room, fits would be thrown, security would be called and a reporter would be expelled. So I kept it quiet.

I was three-quarters of the way through when a dark-skinned Hispanic woman, who was maybe a little younger than me, said, “Yes, I’m her roommate.”

“I’m Carter Ross. I’m working on a story for The Eagle-Examiner. What’s your name?”

“Alison Coutinho,” she said, seemingly accepting that the newspaper must do stories on all car accidents and that it wasn’t at all unusual to be approached by a reporter in an emergency room.

“Is Jessica okay?” I asked.

She let her shoulders slump. “Someone from the hospital called and told me Jessie asked for me. But now that I’m here, the nurses won’t tell me anything because I’m not related.”

I somehow resisted the smartass question about how they figured that out. Alison continued: “But they did say I should stick around and give her a ride home, so that must mean she’s going to be released soon.”

I looked at Alison Coutinho, trying to figure her out. She had on jeans and a T-shirt, hardly what you would call stripper attire. And, without being unkind, I wouldn’t exactly say her figure it was suited to exotic dancing. It was what my very polite mother would call “full.”

“So how do you and Jessica know each other?”

“We go to Kean,” she said.

I’ll be damned. A stripper who really was working her way through college. And a good college, too. Kean University was a small, well-regarded liberal arts school in Union.

“And Jessie, uh…” my voice trailed off, as I tried to be delicate. “She, uh… dances… on the side?”

“I don’t blame her. She makes a lot more money than I do working at the library, that’s for sure,” Alison said. “If I had a body like she does, I’d probably dance, too.”

“Right,” I said. “And how long have she and Senator Ryan been an item?”

Alison slid back in her chair and sat more upright. “You know about that?”

I gave her a lopsided smile. “I’m a newspaper reporter, ma’am, it’s what we do.”

“Well, I’ll let Jessie tell you about that, if she wants to. That’s none of my business.”

“Fair enough. You mind if I slip out and make a quick phone call? I’ll be right back.”

I could feel my hands shaking as I dialed Tina. This was big. Huge.

Tina was, as expected, a little peeved about being hung up on. But she got over it quickly enough when I told her what I had, to the point where she was nearly as excited as I was. Still, her final edict was firm:

“We can’t skewer a prominent man’s reputation on the say-so of three unnamed sources and someone’s roommate,” she said. “You need Jessica Martin on the record, or we’ve got nothing.”

By the time I returned to the waiting room, Alison was in the midst of being joined by a tall, finely boned women with long, straight blond hair. She looked far too high class to be working at a go-go bar in Carteret, which is probably why Lenny liked her in the first place. She had a few superficial cuts on her cheeks and forehead and the beginnings of a nasty black eye, presumably from where her face had mashed into an airbag. She also had her left arm in a sling.

None of which hid the fact that she was stunning.

I’m not saying Jessica Martin’s beauty made it okay for Lenny Ryan to cheat on his wife. I’m just saying she would have made a lot of men question their marriages.

I could feel my heart pounding as I introduced myself, partly because gorgeous women had that effect on me but more because Jessica held my future as a newspaper reporter in her long, delicate fingers.

“Hi Jessie, I’m Carter Ross,” I said. “I’m really sorry about your accident. I’m doing a story about it for The Eagle-Examiner.”

Between her red eyes and runny nose, it was clear Jessie had been crying a lot already this day, and I feared my pronouncement would prompt more sniffling. Or she was getting ready to bury her purse in the side of my head. She was tough to read.

Either way, I knew this was my moment to win her over. It was brief. And there could be no mistake in what I said next. So I went for the kill:

“Lenny Ryan tells me he was trying to find a constituent a job when he lost control of his car and ran it into a building,” I said. “He told me this as he was getting ready to take his wife out for an anniversary dinner. Do you maybe want to tell me a different version of the events?”

A long-dead playwright once warned about the dangers of a woman scorned. Much has changed about the world since he made that observation, but thankfully for this reporter, the fundamentals of it have not.

“Lenny Ryan,” Jessica Martin said, “is a miserably lying worm.”

“Noted,” I said, as I pulled out my pad.

She winced as she adjusted her sling-covered left arm, then calmly said: “You know what that prick told me? He told me he loved me. He told me he was going to leave his wife for me. For six months he had been telling me that. He said he was just going to wait until after the next election, so he could do it quietly. And I believed him. Then he gave his wife a nightgown for their anniversary. A nightgown!”

“This all… this is about a nightgown?”

“Yeah. He had let me borrow his car to run an errand and I found it in the backseat. It had a note attached and everything: ‘To my darling Priscilla, Thank you for 38 wonderful years. Love, Leonard.’ It was from Victoria’s Secret. What kind of man gives his wife a Victoria’s Secret nightgown and writes a note like that if he knows he’s going to leave her?”

“So you found the nightgown in the backseat and… drove his car into a wall to get back at him?” I asked, already dreaming of the headlines that could result from this. Whether it’s Monica Lewinsky’s blue dress or O.J. Simpson’s bloody glove, a big story often needs a small image to make it pop. Mrs. Ryan’s nightgown would serve nicely in that regard.

“He loved that car. He probably loved that car more than me and his wife combined,” she said, then stopped and smiled wickedly. “The fact that I drove it into a wall was purely an accident, of course. I was just so distraught I must not have been paying attention.”

“Of course,” I concurred. “And that will be noted in whatever I write.”

“Thank you.”

“I am curious, though: Why drive it—accidentally, of course—into the go-go bar?”

“Well, you know he owns that place, right?”

For at least the third time that night, I utterly failed at tamping down a grin. “No,” I said. “I was unaware of that. And I’m pretty sure his constituents are unaware of it, too.”

“I know they are. He told me he had it hidden and that the press could never find it. He had made me a part owner and was going to let me manage it so I could stop dancing. I’ve got the paperwork in my purse. Want to see it?”

Within ten minutes we had left the hospital and found a Kinkos, where I made photocopies of all the incriminating documents I needed. Leonard Ryan was assigning a 10 percent stake in the Roxy’s Go-Go to one Jessica E. Martin.

I got Jessie’s cell phone number and a few more pertinent facts about her relationship with the Senator. It had started when the club manager showed Ryan a picture of their newest dancer, this breathtaking blond. The next thing she knew, she was the object of Lenny Ryan’s rather relentless affections—which included everything from poetry and love letters to cash and jewelry.

And, yeah, she promised to dig up some of the poetry for me in the morning. I figured this story was going to have some serious legs. It would be nice to have fresh fodder for the follow.

We parted with an exchange of cell phone numbers and promises to keep in touch, and I pushed my Nova to the very limits of its dubious engineering to make good time back to the Newark offices of The Eagle-Examiner. It was 10 by the time I arrived, and while I had already dictated most of the good stuff to Tina—who had sent it along to her rewrite guy—we had agreed I should do a write-through for the final edition, so I could put it all in my own words.

It was a writing test, all right. But it was a real one. This was my own batter, my own cake. And if I can risk mixing baking metaphors, I was going to turn it into a huge chunk of humble pie for Senator Lenny Ryan.

I was given until 11:30 to write, and I took every second before sending it over to Tina. As she read it, I don’t mind admitting I may have ogled her a little bit. She was sitting in a contorted position, doing some kind of thoroughly impossible stretch that was inspired by either modern Yoga or ancient torture. She had swept her hair up into some kind of clip, allowing me to admire a lovely little cleft where her jaw bone and neckline met. It was the kind of place I decided would require further study someday, if circumstances allowed.

“Not bad for a rookie,” she announced when she was done, shipping it over to the copy desk, which was going to slam it into the three-star edition just before it went to press.

“Thanks for all your help,” I said. “If I may say so, we made a pretty good team.”

She smiled—a broad, full-lipped, lovely smile—but followed it with, “Don’t start liking me. No journalist should want anyone to like them. It makes for bad reporting. You want someone to like you in this business? Buy a cat.”

“I thought it was, ‘If you want someone to like you, buy a dog,’” I said.

“That works for politicians in Washington, but not for reporters at this newspaper. Dogs need people to return home on a regular schedule and walk them. If you get a job here, I guarantee there’d be a lot of nights when you’d come home late to find Rover has peed the rug. Cats are a better fit for reporters.”

“Okay, I’ll get a cat,” I said. “I think I’ll name him Deadline.”

She gave me another alluring smile and we settled into chatting—the where-ya-from, how’d-ya-get-here kind of stuff. Soon, one of the clerks brought up a stack of freshly printed newspapers, making a straight line for me.

“Sal Szanto asked me to give this to you,” she said, then handed me my very own copy of the next day’s edition of The Eagle-Examiner.

It was still slightly damp. And, sure enough, it had a story stripped across the front page with my byline on it. It also had a piece of Sal Szanto’s stationery taped to it. Szanto, like most good newspapermen, apparently valued brevity. Because his note consisted of just two words:

“You’re hired.”

Copyright ©2012 Brad Parks

Brad Parks’s debut, Faces of the Gone, introduced the world to investigative reporter Carter Ross and became the first book ever to win the Nero Award and Shamus Award. His third Carter Ross book, The Girl Next Door, releases this March. For more, sign up for Brad’s newsletter, follow him on Twitter @brad_parks, or go to Brad Parks Books on Facebook.

Good call, Sal. That kid has the chops.

Nice job, Brad. See you in a few weeks!

Fun read, Brad; coupla typos in there though…

See you Friday in Maplewood!