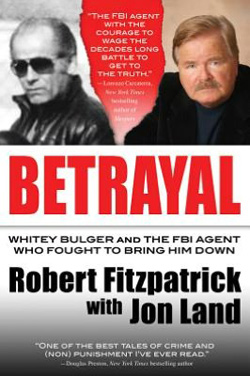

A poor kid from the slums, Robert Fitzpatrick grew up to become a stellar FBI agent and to challenge the country’s deadliest gangsters. Relentless in his desire to catch, prosecute, and convict Whitey Bulger, Fitzpatrick fought the nation’s most determined cop-gangster battle since Melvin Purvis hunted, confronted, and killed John Dillinger.

A poor kid from the slums, Robert Fitzpatrick grew up to become a stellar FBI agent and to challenge the country’s deadliest gangsters. Relentless in his desire to catch, prosecute, and convict Whitey Bulger, Fitzpatrick fought the nation’s most determined cop-gangster battle since Melvin Purvis hunted, confronted, and killed John Dillinger.

In his crusade to bring Bulger to justice, Fitzpatrick faced not only Whitey but also corrupt FBI agents, along with political cronies and enablers from Boston to Washington who, in one way or another, blocked his efforts at every step. Even when Fitzpatrick discovered the very organization to which he had sworn allegiance was his biggest obstacle, the agent continued to pursue Whitey and his gang . . . knowing that they were prepared to murder anyone who got in their way.

Prologue

South Boston, 1984

A few hours before he was murdered on a raw November night in 1984, John McIntyre thought he’d been invited to a party. At least that’s what drew him to a South Boston house owned by Pat Nee, a top associate of Boston’s Irish crime boss James “Whitey” Bulger.

Two weeks earlier, McIntyre had been aboard a ship called the Ramsland when it sailed into Boston Harbor carrying thirty tons of marijuana that would have netted Whitey somewhere between one and three million dollars. But the cargo was seized, putting a sizable dent in whitey’s pocketbook. And it was seized because McIntyre had told federal authorities about the shipment to keep himself out of jail. Believing his informant status still to be safe and secure, McIntyre agreed to go to the party, figuring he’d be able to strengthen his hand with law enforcement even further. Only when he arrived at the house, Bulger stepped out of the shadows and stuck a machine gun in his gut.

McIntyre was thirty-two, of average height and weight, and bearded with dark blue eyes that belied the hardscrabble life of a man who made his living at sea. He had rough, callused hands from handling fishing nets with the texture of razor wire. But in addition to fish McIntyre was also known to carry marijuana, bringing most of his supplies into the Boston area by boat. Small time mostly and not on anyone’s radar, until he caught the attention of the murderous Bulger and his Irish Winter Hill Gang, who were determined to muscle in on Boston’s drug trade in the 1980s.

Whitey was also involved in smuggling large shipments of weapons to the Irish Republican Army in Northern Ireland, for which he commandeered McIntyre as an engineer on a boat called the Valhalla. A military veteran, McIntyre kept his wits about him and didn’t view the criminal lifestyle as anything more than a means to supplement his fishing and boat-building jobs. The money was just too easy and plentiful to turn away from, and McIntyre rationalized his actions by the need to support the young family he was struggling to hold together.

In September of 1984, the Valhalla set sail into the Atlantic with its holds full of guns and ammunition instead of marijuana, or iced swordfish and halibut. The voyage was smooth and uneventful, ending when McIntyre supervised the transfer of arms at sea onto a trawler called the Merita Ann. A few days later, off the coast of Ireland, British authorities boarded the Merita Ann. The weapons were seized and the crew was arrested.

The ramifications of the seizure reverberated all the way back across the Atlantic. Once the Valhalla docked back in Boston, Customs officials took McIntyre and another crewmember into custody on suspicion of gunrunning charges. After routinely questioning McIntyre, they released him. But a few weeks later the Quincy, Massachusetts, police arrested McIntyre on a domestic assault beef. Facing a potential prison stretch, McIntyre agreed to become a government informant and cough up the information on the infamous Irish gang leader’s criminal activities. The feds assured McIntyre he’d be safe, that his informant status would be revealed only to those officials associated with the case.

Now, though, on an autumn night that felt more like winter, John McIntyre found himself staring at the machine gun barrel propped over his belt. Stephen Flemmi and Kevin Weeks, two more of Whitey Bulger’s most trusted lieutenants, grabbed him and threw him on the floor. Then McIntyre watched in horror as Bulger opened his duffel bag of death. He took out a rope, chains, and an assortment of weapons that gleamed slightly beneath the naked lightbulbs with strings dangling from their outlets like spaghetti. Flemmi hand-cuffed McIntyre to a chair and then chained him to it as well for good mea sure.

“We’re gonna have a talk, you and me,” Whitey told him. “I think you’re a rat. Are you a rat, Johnny?”

According to testimony given in court years later by both Nee and Flemmi, Bulger proceeded to break McIntyre’s fingers one at a time until he finally confessed to his role as informant. Between shrieks of pain, McIntyre apologized for being “weak,” claiming he’d panicked, had no choice. Give him another chance and he’d prove himself loyal. He’d tell Customs and the FBI he’d made it all up to keep himself out of jail on that domestic assault charge.

But Bulger, having been told otherwise by at least one of those McIntyre thought was protecting him, wasn’t buying it.

“I think you’re full of shit, Mac.”

“No, no! I fucked up, but I’ll make things right, I swear!”

“Swear to God?”

McIntyre just looked at him.

“ ’Cause God’s not here. I’m here. You believe in God, Johnny?”

McIntyre nodded.

“You go to church?”

McIntyre didn’t say anything.

“Yeah,” Bulger picked up. “What’s God done for you anyway, compared to all I’ve done? And this is how you pay me back. By fucking me”—Bulger backhanded McIntyre across the face—“in the ass.”

He was grinning now, enjoying himself. Bulger knew that John McIntyre had already told him everything, but that didn’t stop him from continuing the mental and physical torture for another five or six hours. When he finally tired of the process, Bulger placed a boat rope around McIntyre’s neck and tried to strangle him. But McIntyre refused to die. Bulger then slammed him repeatedly in the skull with a chair leg. McIntyre still refused to die.

“You want a bullet in the head?” Whitey asked, leaning in close to his ear.

McIntyre nodded, rasping out “Yes” through the blood and spittle frothing from his mouth.

Whitey shot him as promised. The impact threw him over backwards, still strapped to the chair and, incredibly enough, still alive. Flemmi grabbed his hair and pulled his head up while Bulger shot him again, repeatedly.

“He’s dead now,” Whitey said, and then went upstairs to take a nap.

Part One

Coming To Boston

Washington, D.C., 1980

“Fitz,” Assistant Director Roy McKinnon said the day he summoned me to his office at headquarters in Washington in late 1980, “we need an Irishman to go to Boston to kick ass and take names.”

I laughed but he didn’t.

“Any suggestions?” he asked instead, staring me in the eye.

McKinnon was the ultimate straight shooter. He had a square jaw and wore his salt-and-pepper hair cropped military close. I seem to remember he’d been a Marine; either way, there was a directness of purpose about him befitting a military mind-set, right down to the orderly nature of his office, in which nothing, not even a single scrap of paper, was ever out of place. He told me the assignment was important for a variety of reasons. He sounded grave about my new adventure and talked about difficult problems in Boston without specifically outlining what those problems were. Right out of the gate, loud and clear, he ordered me to put Boston on the “straight and narrow.” My initial reaction was it sounded like déjà vu, having had an assignment in Miami in the mid-to-late 1970s where, in fact, I did kick ass and take names in the ABSCAM investigation that nabbed numerous public officials, including a sitting U.S. senator. ABSCAM was a sting operation that targeted corrupt politicians and possible law enforcement personnel. I supervised the sting undercover, getting targets, including Senator Harrison Williams (D-NJ), to implicate themselves on tape. It was, in all respects, the FBI at its best.

I was Miami’s Economic Crimes (EC) supervisor at the time and also worked undercover on our yacht, the Left Hand. I had procured the sixty-foot yacht from U.S. Customs, which had acquired the boat as part of their seizure in a major drug sting. We needed a “comeon” for our undercover gig and the Left Hand fit the bill beautifully. Before we docked the boat in Boca Raton, my squad cleaned it and installed surveillance equipment around the large foredeck, which was perfect for entertaining, and inside a trio of well-appointed cabins for private meetings. Soon, the Left Hand became an attraction and developed a notorious reputation in South Florida, fostered in large part by our undercover persona.

ABSCAM became the biggest case ever on the EC squad, recovering millions of dollars in fraudulent securities and various white-collar crime scams. We decided to have a final party and invited all of the criminals we had evidence on to attend. We equipped the boat with additional surveillance equipment and captured our future arrestees on tape. The “Sheik,” an undercover agent, was posing as the wealthiest person in Miami, a connected Arab. While I sat up in the control room with the Strike Force chief, we encountered a problem. Senator Williams had appeared and demanded that he be allowed to attend our party. We declined and he demanded to see the Sheik anyway.

Under orders from FBIHQ we were told in no way could the senator board the boat. The Strike Force chief insisted we finish the sting, but FBIHQ demanded we close the operation down. HQ’s concern was that allowing the senator to come aboard a boat laden with druggers, prostitutes, and criminals might be seen as a form of entrapment.

Afer much deliberation with FBIHQ, the FBI Special Agent who was playing the sheik, told me, “Bob, I won’t allow alcohol, drugs, or anything that could harm the senator aboard my boat!”

I laughed at him and said, “You’re crazy. What kind of party are we supposed to throw?”

He looked at me and, in the dignifi ed role and manner of a true sheik, said, “I am the sheik and I won’t let it happen!”

The party went forward on the pretext its host, our undercover sheik, could not be in the presence of drugs or alcohol for Muslim religious reasons. The recorded conversation and surveillance tapes played at Harrison Williams’s trial dispelled any inclination that we had entrapped the senator, and he was found guilty and convicted in federal court by his own voice. I took no pleasure in taking down a sitting U.S. senator; to me, he was a criminal who was extorting agents of the federal government sworn to uphold the law.

In this unique experience, I became no stranger to corruption, learning how to dig it out and destroy it. And that’s why I supposed I was being transferred to Boston.

Tom Kelly, my former boss in Miami and an FBIHQ deputy at the time, had filled McKinnon in on my experience in ABSCAM, making it plain that I had cleaned up Miami and could probably do the same in Boston. Contrary to what was apparently going wrong up there, a key factor in the decision to send me north was my ability to pursue investigations without anyone tipping off the press or the target. ABSCAM was successful because all FBI agents working for me diligently did their jobs and, in spite of the high priority of investigating high-ranking government officials in a major scam, we brought it off without a single leak. Not one.

I was on a career fast track, groomed, I anticipated, for even bigger things to come. Not bad for a kid who’d grown up in a church- run institution, an orphanage on Staten Island called Mount Loretto. But that’s where my dream, this very FBI dream, was born.

Chapter 2

Astoria Queens, 1944

“I have to pee,” I whined to the cop. Then I screamed, “I really have to pee!”

The cop, whose name was O’Rourke, looked at me indifferently. I thought he could care less until he knelt, picked me up, and carried me to the kitchen sink. After I relieved myself, he carried me back into the living room of my New York City apartment demanding clean underwear and clothes from my warring parents. Officer O’Rourke, who came from the 14th Precinct, had five kids of his own, so I guess I should consider myself fortunate he was the one who responded to yet another fight between my parents that was loud enough to rouse the neighbors.

“You guys better calm down in there,” he called to my mother and father. “Your son’s coming with me. Pack some clothes in a bag.”

They’d been warned what the upshot of one more complaint would be, but that hadn’t stopped their constant onslaught in the least. This time O’Rourke had responded after some neighbors complained that “the people next door were going to kill each other.” O’Rourke knew if he couldn’t stop my parents from doing that, he could at least stop them from doing it to me.

boxes were attached to the cottage wall—these held our school clothes, shoes, and field clothes sometimes. All of our clothes were hand-me- downs, not at all fashionable or comfortable but better than nothing. In the lavatory we had stations that held toothbrushes, soap, and a towel on a hook. There were eight commodes and six urinals for sixty-six children. Half the cottage took showers at a time.

For sleeping, each of us had a cot on either the second or third floor. Bed wetters, all thirty of them, were crammed into the third floor, and the stench of urine wafted throughout the cottage, and was especially bad in the summer months when the heat putrefi ed the stench further and in the dead of winter when the windows were all closed. I would pass through all six cottages as I grew older, the stench evolving with the years too, though the routine and accommodations otherwise remained unchanged.

My two older brothers, Larry and Gerard, and older sister, Diane, had been moved to the Mount as well. But I hardly ever saw them. The older children almost never mixed with the younger under any circumstances, siblings or not. I’d often stare out the windows or across the fields, hoping I’d spot one of them. In my mind I saw myself lighting out toward Larry, Gerard, or Diane. But even if I’d glimpsed them, I’d never have done it. I was much too scared to dare challenge authority or break the rules. We were sometimes able to sit together in church on Sundays, but that was it. Regimentation and regulation were everything. Corporal punishment was the rule, not the exception.

Well, not quite. There was also the brutality in this world where power was the only currency. I remember walking across the bridge that ran near a drainage ditch between the dormitory and dining hall. The bridge’s structure was worn and it shook a bit when packed with young boys rushing to lunch to beat the February cold.

One wind-blown dreary day, as our counselors led us across the bridge, one of the ten-year-olds from my cottage yelled out, “Fuck you!”

“Who yelled that?” the counselor named Scarvelli demanded, stopping everyone in their tracks.

All of us remained silent.

“I’m gonna ask youse guys again: who yelled that?”

“Last chance,” another especially sadistic counselor, Farber, chimed in. “Or you all pay.”

But there were no rats in this group, so the counselors marched us straight back to our cottage where we were told to stand fast near our “boxes” directly beneath the hissing steam pipes that heated the buildings—or at least were supposed to.

“All right, you little assholes, grab the pipes,” counselor Farber ordered. “Everybody holds on until somebody talks. Let go and we’ll beat the shit out of you.”

The pipes clanked and hissed as the hot steamed water coursed through them. I held tight, feeling my hands beginning to blister, and watched my first cottage mate drop to the floor to be beaten and interrogated, then the second, followed by a third and a fourth.

When the bulk of us finally dropped, it was too much for the counselors to handle. They had us stand at our boxes and demanded each boy come into the wash-up area where one by one we were system atically berated and beaten again. Since I was the last to fall, they beat me only once but twice as hard. They had the power.

No supervisor interceded. Either they didn’t know what was going on or they didn’t care. Scarvelli and Farber beat some of the boys worse than others, including me since I was one of the youngest and smallest. But I didn’t tell them what they wanted to know. No one did.

And neither did anyone rat out Scarvelli and Farber. We all knew that if we ratted out the counselors, we’d be beaten much worse and end up longing for the blisters the steam pipes left on our small hands. The message was clear and all of us got it: They were bullies and we were helpless against them.

My escape from times like these came in the form of the old-time radio programs playing over Sister Mary Assumpta’s radio. She was kind enough to leave her door open after lights out so the sound filtered out into the dormitory. It was often garbled and not very loud, but I was entranced, whisked away to a world dominated by heroes where the good guys always won and the bad guys, the bullies, lost.

I’d lie in my second-floor dormitory bed listening to The Lone Ranger, The Shadow, and especially, This Is Your FBI. I say especially because I was already “old” and jaded enough by experience to know the difference between what was real and what wasn’t. Neither the Lone Ranger nor the Shadow could swoop in and save me, because they weren’t real, but the FBI was. I would lie there and imagine myself becoming a swashbuckling, crime-fi ghting hero someday, in large part because my life up to that point had been so bereft of them. In all of the “cops and robbers” games, I was always the FBI agent who got his man. I thought of O’Rourke and the others at the 14th and how kind they were.

It might sound corny, but in the Mount’s big, Gothic church there was a huge stained-glass window. It showed Jesus with children around him and the inscription read, “Suffer the little children come unto me for their’s is the Kingdom of Heaven.” Jesus became my rescuer, to be replaced later, in my “cops and robbers” game, by the FBI.

In those minutes, as I lay with my eyes closed listening to the garbled tales of This Is Your FBI, I was spirited far away from the Mount to places where I was happy and secure, reliant on no one and fearing not a single soul. And maybe someday I was going to become for the world, and the country, what no one had ever been for me.

I’d found my dream, and through the years and pain that followed, I never let go of it.

Chapter 3

Boston, 1981

The FBI had lacked an authoritative face since the heyday of J. Edgar Hoover’s reign as chief. His fall from grace had exposed plenty of what was thought wrong with the Bureau and unfairly dwarfed much of what was right. Certainly no one individual could restore the lost luster and repair a tarnished image. But appointing successful, high-profile agents in top-level positions seemed the next best thing. My wife and two young boys, unfortunately, were less thrilled about the prospects of moving yet again. It seemed as if, in my fifteen years with the Bureau since my marriage, every time we’d just about get settled, I was transferred. Coming to a top-ten office like Boston to take over as ASAC (Assistant Special Agent in Charge) represented the pinnacle of my career, and I could see myself staying in the city for some time.

But my wife wasn’t buying that, and my marriage dissolved. My wife was tired of sharing me with a dream that knew no end. I tried to convince her that Boston could be just that, the final stop. But she feared I’d end up returning first to Washington en route to yet another promotion and posting. She believed I loved the Bureau more than her.

She was both wrong and right, something I considered often on long, lonely nights in my small apartment, where it always seemed dark outside.

My entry into Boston had been through the proverbial back door. On the face of it I appeared to have a routine FBI transfer with no ulterior motive; there was no paperwork about my “official” mandate. Just an Irish guy going to an Irish city on another assignment.

I came to Boston straight from my post as head of the investigative nerve center of the FBI in Washington, D.C., the Special Agent Transfer Unit. SATU, an unusual sounding acronym, was the FBI unit from which agents were transferred from particular offices throughout the U.S. and abroad to other assignments, and from where investigative resources and funding were allocated to the FBI fi eld offices worldwide. Not a single major case unfolded without my knowledge and involvement. As a bureau chief I had the responsibility to make recommendations after reviewing requests for manpower, investigative resource allocation assistance, and “specials.” Major cases and specials were defi ned as the most important investigations, demanding supplemental manpower and sometimes extraordinary technical assistance in the form of surveillance equipment as advanced as any in the world at the time.

That’s how I first became acquainted with the problems in Boston. Word was the agents there had taken their mandate to bring down the Italian mafia too far by allowing their informants, including one named James “Whitey” Bulger, free rein on the streets in return for providing intelligence that often produced nothing. Some in the Massachusetts State Police were livid that the FBI was letting a former street thug, like Whitey Bulger, currently running the vicious Winter Hill Gang out of South Boston, get away with murder— literally. Specifically, the execution of a major bookie and FBI informant named Richie Castucci. The Massachusetts State Police (MSP) didn’t buy the Boston FBI office’s conclusion that the Italian mob was responsible for Castucci’s murder, not for one minute. More specifically, the MSP even accused a pair of FBI agents, John Morris and John Connolly, of feeding intelligence directly to Bulger, protecting him and aiding his ascent up the ladder of criminal power in the New England underworld.

The Bureau took its motto—Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity—seriously. But in Boston, if suspicions about Richie Castucci’s murder were true, that motto had become more option than mandate.

My new job as Assistant Special Agent in Charge (ASAC) of one of the top ten Bureau offices in the country was to handle all organized crime for New England and command the Drug Task Force. Other duties that co-mingled with the organized crime investigations included WCC (White Collar Crime), Public Corruption (PC), and so-called nontraditional Organized Crime (OC) involving the Irish thugs who roamed free through the closeted, insular society of Charlestown, Somerville, and South Boston.

Larry Sarhatt, the Special Agent in Charge (SAC) of the Boston office, picked me up at the downtown hotel that served as my temporary residence on a damp chilly day in early 1981—the rain that had been forecast had yet to come. He drove me to the FBI offi ce at Government Square, near the Italian North End in the heart of the former Irish bastion, Scolley Square, where we occupied the whole of the sixth floor. My office overlooked the front of the building, the infamous Boston traffic jams leading to snarled streets virtually all day long, the honking of horns and blowing of sirens providing a background din that became as familiar as the clanking of the corner radiator or the soft hum of the air conditioner. I could walk out my door and view the workings of most of the agents serving on any number of the squads I’d been placed in command of. Some of the more junior ones worked out of spaces that were little more than cubicles or shared cramped offices—well, smaller than mine. The office fl oor was always busy but never frantic, since so many of the agents spent their days in the field on active investigations, of which there were plenty. We had agents who lived for the blue lights and sirens, and those who did not. I’d met a number of them and knew others by reputation, enough to be sure they made for a good lot with plenty of solid casework and convictions to their credit.

Larry Sarhatt was eager to get on with business and welcomed any assistance, especially in the manpower area. He went through the prospective “priority one” La Cosa Nostra (LCN) cases on deck in Boston, specifically the investigation of Gennaro “Jerry” Angiulo, who reported directly to the head of the New England mob, Raymond Patriarca, out of Providence, Rhode Island.

Jerry Angiulo was the underboss of the New England LCN, presiding over sixteen ranking members who reported directly to him. Everything about these wiseguys was steeped in their own bloody traditions, such as the initiation ceremonies that offered a sense of code and moral backing to their actions, as loathsome and reprehensible as they were. The Godfather movies and “mafia” pulp fiction glamorized the culture, enticing wannabes to emulate the fi ctionalized images.

Not so the case for the members of the Winter Hill Gang. These Somerville wiseguys were decidedly Irish muffs tagged by the FBI as a nontraditional group of the organized crime element. We knew approximately twenty of these guys were in leadership positions, supervising three hundred soldiers and grunts, all under the auspices of Bulger and his right-hand man, Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi. It was abundantly evident that both groups had their preferred methods of violence and murder. The Irish wiseguys would “frag” a bunch of people to get their target, while the Italian wiseguys would just garrote the one target and stuff him in the trunk of some car. The Irish were definitely more homegrown, all in all, than the Italian mob, which led them to be even more insular.

I knew Bulger as a thug, a street enforcer who’d spent a quarter of his life behind bars, including a stretch at Alcatraz and another at Leavenworth in Kansas. I’d heard he prided himself on being a tough guy who inspired fear in allies and enemies alike. Ruthless and brutal, his rise to the top of the Winter Hill Gang in the wake of Howie Winter’s imprisonment attested. He wasn’t a big guy physically, and word was he wasn’t just street smart; he was smart, period, capable of playing chess while those around him opted for checkers. But he played for real, to which the forty-three murders he’s allegedly responsible for more than attest.

Sarhatt briefed me on the informant situation, explaining that a major informant against the Angiulo family, Bulger himself, was be ing videotaped and surveilled at a mob garage on Lancaster Street in downtown Boston by the Massachusetts State Police (MSP). MSP grew incensed when Bulger and his associates suddenly and inexplicably clammed up, claiming that FBI agents John Connolly and John Morris, Bulger’s Bureau handlers, had leaked word of the investigation to their prized informant. Sarhatt informed me that Colonel John O’Donovan, the much decorated and current head of the MSP, suspected as much and was livid over the fact that nothing had been done about it. Worse, he was convinced this was an ongoing problem.

An old-fashioned cop to whom a bad guy was a bad guy, O’Donovan was a stout, rangy man with sinewy muscles born of boxing as a kid and old-fashioned weightlifting into his fifties. He had a shock of balding gray hair that shifted with every toss of his head, and a single piercing blue eye that looked tired whenever I saw him.

He had been shot in the eye by a gangster early in his career, earning him a much-deserved deserved reputation. The real deal when it came to tough. In O’Donovan’s mind, Bulger and Flemmi were nothing short of stone killers and the last people the FBI should be doing business with. He followed protocol by informing the Boston FBI office of his intentions to find incriminating evidence against Bulger and Flemmi in any number of crimes, specifi cally murder.

Sarhatt’s and the FBI office’s dilemma was that they could not officially tell the MSP that their targets were informants for the FBI. Politics and internecine conflicts never entered the picture for O’Donovan or, if they did, were superseded by the bad blood Bulger was tracking through the city.

Larry Sarhatt was caught in the middle of this dilemma between loyalty to his own agents and his greater responsibility to the Bureau. The only way he could reconcile things was to determine whether to keep Bulger on the FBI books as an informant or “close” him. In his heart, I knew he wanted Bulger cut loose. He’d come to that conclusion after interviewing Bulger himself barely a year before, only to be overruled by Jeremiah O’Sullivan, the prosecutor running the federal Organized Crime Strike Force. O’Sullivan, along with FBIHQ in Washington, wanted Bulger to remain open as a top echelon criminal in for mant as long as he continued to provide information about the mob families out of Boston and Providence. He was, in their minds, too valuable to close. But the real question was just how valuable was Whitey Bulger, and answering it became my first mandate.

I wasn’t a fan of O’Sullivan from the get-go. He seemed too much the button- down bureaucrat who wore his ambition on his sleeve. He was thin and pale, fond of flashing a narrow condescending smile to create a sense of false camaraderie. I remember his hair looked to be glued into place, every word and gesture made as if the cameras weren’t too far away. I saw him in federal court several times, his spine straight, every move looking rehearsed—from the moment he first stepped into the building to the time he climbed back into his car parked outside Government Center.

Sarhatt, on the other hand, was a traditionalist whose nonflashy, by-the-book, pragmatic style had him running afoul of agents beholden to the more pop ular criminal agent SAC he’d replaced over a year before. So he told me he was relying on my background to make sense of the muddle. For manpower and resource management, he looked to my previous major case and experience at HQ; for assessment, he looked to my training in the Behavioral Science Unit at the FBI Academy, where I gained expert knowledge in profiling and polygraph as well as expertise in the area of abnormal criminal psychology. He knew operationally I had conducted major investigations all over the country—from New Orleans to Mississippi to Memphis to Miami—both undercover and not, and had handled complex cases, always achieving favorable resolutions. In other words, I was a “closer,” and that’s exactly what he needed on his side now.

More to the point, in retrospect, I was sent to Boston to offer all parties political cover. The thinking on the part of McKinnon and others was that the success I’d achieved in the ABSCAM investigation would trump the dueling viewpoints that had all but obscured any rational assessment of how much Bulger was actually contributing to the cause. And since I was an outsider, my objectivity could not be called into question.

Larry Sarhatt and I ended our first meeting with a simple mandate: If everything suggested by the Richie Castucci murder was true, we would tackle the problems in Boston once and for all.

Jon Land is the bestselling author over 25 novels. He graduated from Brown University in 1979 Phi Beta Kappa and Magna cum Laude and continues his association with Brown as an alumni advisor. Jon often bases his novels and scripts on extensive travel and research as well as a twenty-five year career in martial arts. He is an associate member of the US Special Forces and frequently volunteers in schools to help young people learn to enjoy the process of writing.

Okay, so I think I need a twelve step program of some sort. I am becoming THE groupie for all things Whitey Bulger. Thanks for this brilliant excerpt.

Don’t worry- we think we might need to add a special tag for all the Whitey-related stuff we’ve had, but it is fascinating, and keeps coming!

Hey, Terrie, I’m Jon Land, co-author of BETRAYAL, and I’m happy to report you’re going to have to delay your entry into the Bulger 12-step program until after you’ve read this book. Yes, there has been a ton of stuff written on all things Bulger. But this is the first book ever written from the inside by someone who was actually was there and lived every agonizing second of it. Bob Fitzpatrick was the most celebrated FBI agent of his time and his mandate in coming to Boston was clear. The problem was he did his job too well and too many very powerful people both in and out of the Bureau were going to end up with egg on their face if they’d acceded to his recommendations to close Bulger as an informant and arrest him. The rest makes for fascinating, and riveting, drama. You will not be disappointed and I look forward to hearing your comments on the book. You can reach me at jonlandauthor@aol.com. Can’t wait to hear your thoughts! Jon

Music to my ears, Clare, as BETRAYAL’s co-author. The other books on the subject were indeed fascinating but this book will go down as the definitive study of the era written by someone with a bird’s eye view of the whole sordid time–what Peter Gelzinis brilliantly called in the Boston Herald, “Whitey and Stevie’s Golden Years.” If you’d like I can send you his whole column written in the wake of the McIntyre trial at which Bob Fitzpatrick’s testimony proved pivotal. Stay in touch at jonlandauthor@aol.com.

It was quite exciting reliving FBI adventures and sad that some turned out so bad. This case is still going strong and Bulger’s trial is due in June of 2013. He claims he had immunity to commit murder by the government and hearings in USDC are on going. I did a big presentation To FOX in LA and they will run monthly stories up until June of 2013. I am proud to have received a submission to the Edgar Awards and other awards. Jon did a great job in assisting me and deserves a lot of credit. I believe all of you will enjoy this book; after all, it was written in most part for the public for honest and better justice. BF

Having just finished reading the ‘Gangster Squad’ as well several biographical books concerning the FBI and so called ‘Gangsters’, I find it incredible that, even in today’s so-called ‘civilised’ society, there are agencies, institutions and governments who have been, and are complicit, either by ignorance or wilful intent, in assisting the criminal elements of our society. I shall be obtaining a copy of’ Betrayal ASAP. Having read the reviews I am sure it will be a rivetting and eye-opening read.

Interested in HARD ROCK? How about Kiss band? The band is on a tour now all across USA and Canada. Visit http://www.piamco.com.co/producto/mosaico-cover-it-m040/ to know more about KISS tour in 2019.