Smaller is Better: Mysteries Set in Small Towns

By M.L. Longworth

November 13, 2019

The painter Paul Cézanne was never comfortable with the Paris art scene, despite claiming he would change it “with an apple” (and he did). He was mal à l’aise with people, especially the fashionable, the wealthy. He once said, “The world doesn’t understand me and I don’t understand the world, that’s why I’ve withdrawn from it.” Where did he go? Back home, to sleepy Aix-en-Provence, which at the time of his death in 1906 (he had been out walking, to paint, and caught flu) the train didn’t even stop here.

My adopted hometown has grown; now 143,000 people live in greater Aix. But the downtown, la vieille ville, is still as compact as it was in 1900, enclosed—protected, in a way—by what was once thick stone walls and is now a ring road. One can walk across it in twenty minutes or so. You can’t be in a hurry, or have enemies, because you’ll run into them. You’ll be forced to stop and exchange the bises. Its small size means that everyone knows everyone—very helpful to a detective solving a mystery (or, reversely, he or she could get led astray by a well-wishing neighbor who thinks they’ve seen something).

When I began writing a mystery novel I thought of Inspector Morse’s Oxford and quickly saw the similarities: historic university towns, small and compact and yet cultured and busy. How very familiar Oxford’s High Street, college greens and wood-paneled dining rooms are to us if we’ve read the books or watched the series. Even Oxford’s Randolph Hotel bears similarities to Aix’s elegant café Les Deux Garçons, where a teenage Cézanne would argue with his best friend, Emile Zola (I prefer its neighbor down the street, the lesser-known and even quainter Le Grillon, where my characters meet regularly for coffee).

While Oxford and Aix-en-Provence are very real towns, even smaller St. Mary Mead, Agatha’s Christie’s fictional setting for Miss Marple, is entirely invented. Even its county changes from book to book all fictional, from Downshire to Downside to Radfordshire. There is real attraction in setting a mystery series in a village, town or small city, especially a quaint one: the small size means that everyone in everyone else’s business. And the writer can indulge themselves with descriptions of streets and buildings that they know well, either because they live there, like Dexter did in Oxford, or because they’ve imagined the whole thing up. Agatha Christie enjoyed sketching floor plans and maps of her settings, all wonderfully preserved in her notebooks, now archived in the library at the University of Exeter.

Having the detective walk across a small city, to and from appointments, gives the writer a chance to describe what they see, and the reader some moments of vivid armchair travel

The small-town setting permits characters to reappear in later books, giving the writer a chance to develop characters, and overlap storylines. It’s being frugal, yes, but not cheap if the characters develop over many books; it adds richness and it’s comforting for the reader, like meeting up with old friends. When we read, or even reread a series, we have our favorite people: The handsome Welsh doctor in St. Mary Mead, who gives medical tips to Miss Marple; Donna Leon’s Guido Brunetti’s wealthy Venetian father-in-law, a Count, and a continuous source of information useful to the commissario. Or, they can be not at all employed in a useful profession to a detective, but just eccentric, like my own Philomène Joubert, an elderly gossip who sings in the same choir as the principle character’s mother-in-law. When chatting with Philomène, who’s always downtown pulling behind her a weathered shopping caddy, examining magistrate Antoine Verlaque knows he might get some insight or other, even if it’s just when to expect the next mistral wind.

The shops and services in the town, too, will serve multi-fold: in scene settings; with character development, proprietors either eccentric or mild-mannered but who can help the detective. In small towns you know the person selling you the cake, often even by name. The shop can even do their sensory work, especially if it sells food (think of Brunetti in Venice’s small bars and back street restaurants, or at the Rialto market). As a writer you describe not only appearances but how things smell, and taste, and feel. If the setting is abroad, the reader learns about various local epicurean delicacies, and after a particularly successful passage hopefully is encouraged to run to the nearest fine food shop and buy the North American equivalent, or at least sit back with a glass of wine and some cheese. And there can even be a subliminal message for the reader, as there are in my books when Antoine or his wife, Marine, buy cheese from a small shop, or wine from another equally small shop up the street: buy from your local independent merchants! Save our towns from the shopping malls and supermarkets! (In France, hypermarchés, and they’re popping up like mushrooms, with many downtown smaller shops closing to reopen as a clothing chain).

Having the detective walk across a small city, to and from appointments, gives the writer a chance to describe what they see, and the reader some moments of vivid armchair travel. Colin Dexter, Morse’s beloved creator, said, “The huge value for me as a writer is that, even if people haven’t been to Oxford, they would love to be in the city.” This is possible in compact cities like Venice and Oxford, and I knew it would the same in Aix, where I’ve lived for over twenty years. When we walk we see details in streets and buildings that can be missed even on a bicycle. And if the town is historic, and stunning, as Cézanne knew his hometown was (probably the real reason he returned for good) the writer’s job is all the easier. I enjoy the contrast, too: a crime that occurs in a beautiful setting is surprising, sometimes shocking, and entirely believable.

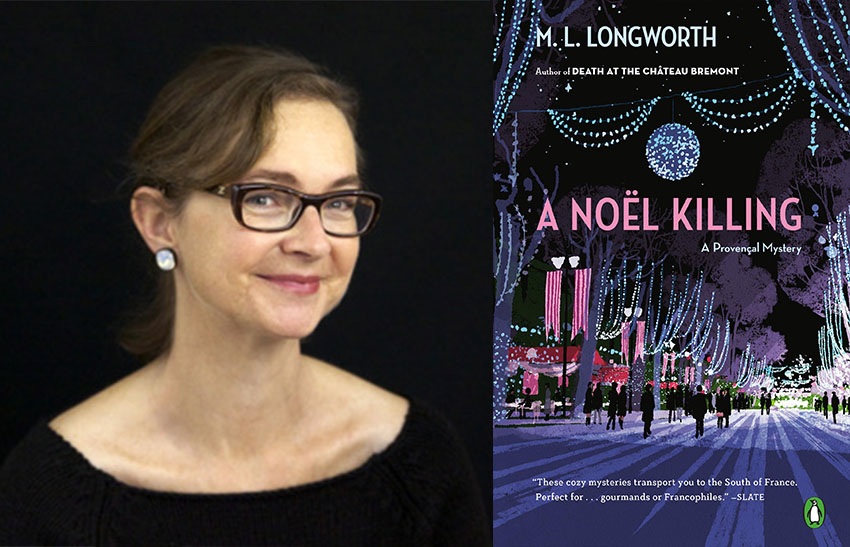

*Photo credit Marcus Lyon

About A Noël Killing by M.L. Longworth:

Christmastime in the south of France is as beautiful as ever, but when a shady local businessman drops dead in the middle of the festivities, Verlaque and Bonnet must solve the case while keeping the holiday spirit alive

Antoine Verlaque, examining magistrate for the beautiful town of Aix-en-Provence, doesn’t like Christmas. The decorations appear in the shops far too early, festive tourists swarm the streets, and his beloved Cours Mirabeau is lined with chalets selling what he regards as tacky trinkets. But his wife and partner Marine Bonnet is determined to make this a Christmas they can both enjoy, beginning with the carol sing at the Cathedral Saint Sauveur, a beautiful service in a packed church.

Just as the holiday cheer is in full swing, a man is poisoned, sending the community into a tailspin. The list of suspects, Verlaque and Bonnet quickly discover, almost fills the church itself, from the visiting vendors at the Christmas fair to the victim’s unhappy wife and his disgruntled business partner. In A Noël Killing, with the help of an ever-watchful young woman named France, the pair must solve the murder while the spirit of the season attempts to warm Verlaque’s stubborn heart.