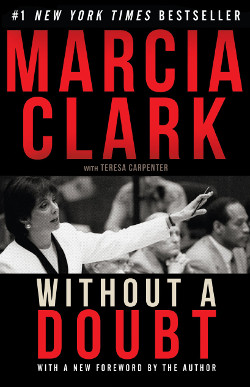

Without a Doubt by Marcia Clark (w/ Teresa Carpenter) is the true crime memoir from the head prosecutor in the O.J. Simpson murder trial, rereleased with a strong new foreword from Ms. Clark addressing how her views—and the public's—have shifted.

Without a Doubt by Marcia Clark (w/ Teresa Carpenter) is the true crime memoir from the head prosecutor in the O.J. Simpson murder trial, rereleased with a strong new foreword from Ms. Clark addressing how her views—and the public's—have shifted.

Despite years of shunning “Trial of the Century”-related publicity, Marcia Clark found herself back in the spotlight in 2016—more than two decades after she led the failed criminal prosecution of O.J. Simpson.

Not only did Sarah Paulson’s nuanced, empathic portrayal of her in FX’s hit mini-series American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson earn the actress an Emmy nomination, but it helped to redefine Clark’s image and made her something of a feminist icon among Gen Xers. Further, Clark participated in ESPN’s expansive documentary, OJ: Made in America, contributing to an important and revelatory discourse about race relations in America. Taken as a whole, the two projects sharply illuminated how factors such as race, celebrity, and sexism contributed to a subversion of justice that resulted in Simpson’s acquittal.

Check out the Rev. Spyro's coverage of American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson!

This “epiphany” was not an eye-opener for Clark, who had made her case to a downtown Los Angeles jury in 1995 (and, by default, a national television audience of millions) in the aftermath of the Rodney King verdicts—and then again to the world at large in her #1 New York Times bestselling Simpson trial memoir, Without a Doubt (1997), co-written with Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Teresa Carpenter. Last spring, that book was reissued by Graymalkin Media in digital, hardcover, and paperback editions; Clark contributed a new foreword that addresses how her views have shifted, as well as the shift in public opinion.

In Without a Doubt’s Prologue, Clark writes: “Just as all politics is local, all good history is personal.” She delivers on that promise, inviting readers into her head and heart in a nearly 500-page opus that opens on the morning of Monday, June 13th, 1994—the day after the slayings of Nicole Brown and Ronald Goldman.

Clark—a newly single mother of two who’d just filed for divorce the week prior—was at her desk when she received a phone call from Detective Phillip Vannatter of the LAPD’s Robbery/Homicide Division apprising her of the murders and outlining the preliminary evidence against their person of interest: O.J. Simpson. The name brought forth a vague recollection (“I just had the general impression that he was a has-been.”), and she assured him that he had enough to pursue a search warrant.

A fourteen-year veteran of the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office, Clark—who’d won nineteen of twenty previous homicide cases, including the prosecution of Robert Bardo for the murder of actress Rebecca Schaeffer—had yet to realize the import of Simpson’s celebrity on what was to come. In fact, she initially found herself buoyed by the promise of a new case in which to immerse herself.

The warning signs, however, showed themselves almost immediately—first in the LAPD’s turf war with the D.A.’s office and their deferential treatment of Simpson, who they initially refused to arrest despite strong circumstantial evidence against him, his lack of an alibi, and a truly incongruous statement; and then in the sympathetic public response to Simpson’s failure to surrender and subsequent unlawful flight (more commonly referred to as “the Bronco chase”).

If those attitudes were a harbinger of things to come, Clark still took some measure of comfort in the proof of the case (“the most massive and compelling body of physical evidence ever assembled against a criminal defendant”); blood, hair, fibers, shoe prints, and a pair of gloves—one recovered at the crime scene and the other at Simpson’s estate—all pointed to Simpson’s guilt. Further, he had a history of domestic violence against his ex-wife, was allegedly stalking her in the months prior to her death, and had no alibi for the time of the murders, buttressing the prosecution’s ability to demonstrate motive and opportunity. Unfortunately for Clark and company, it was Detective Mark Fuhrman who discovered the bloody glove at Rockingham—a seemingly innocuous event that would have devastating consequences.

Clark quickly got wind of the defense’s intention to play the race card and make Fuhrman the fall guy—a strategy that became the cornerstone of their case once Johnnie Cochran joined the so-called “Dream Team.” Given the social climate, she and her colleagues knew they were fighting an uphill battle—particularly given the complexion of the predominately female, African American jury—and quickly came to view the possibility of a hung jury as their best shot.

But, Fuhrman’s racism (and not Christopher Darden’s ill-conceived glove demonstration)—though technically irrelevant to the proceedings—was the death knell to the prosecution’s case, and any hopes of justice were vanquished as one “N-word” superseded another (Nicole). The jury would answer Cochran’s call to “send a message” by deliberating for less than four hours on a case that took 372 days and nearly 48,000 pages of trial transcript.

When contemplating that verdict, Clark professes: “I am not bitter. I am angry.” And, that anger is both palpable and pervasive. She rails against a disingenuous and incendiary defense (“Whole neighborhoods of Los Angeles…could have gone down in flames, Johnnie, because of your irresponsible, inflammatory rhetoric”). She also lights into the dismissive jury, who she paints as “every bit as addled by racial hatred as their counterparts on the Rodney King jury.” (In her new foreword, she professes a deeper understanding as to why minority jurors were so suspicious of authorities and thereby susceptible to the contradictory and illogical conspiracy theories proffered by Simpson’s lawyers.) But, the majority of Clark’s wrath is directed at Judge Lance Ito. She maintains that he was enamored with celebrity, awed by the defense, unapologetically sexist, and wholly incapable of maintaining control of the courtroom. As she argues: “But how can you expect a clown to stop a circus?”

Further, Clark debunks defense theories of evidence destruction, missing blood, planting, and contamination point-by-point with cool, calm logic. So, too, the notion that the case should have been tried in Santa Monica (i.e., before a white jury). Ultimately, Clark asserts that Simpson’s fame coupled with a misplaced sense of loyalty from the black community proved insurmountable—a contention that is only now getting its due.

Beyond case-specific criticisms, Clark argues that the jury system is inherently flawed and often serves to exclude the most well-educated, civic-minded citizens due to hardship. In addition to advocating for reform, she offers a plea: “The next time you receive a jury summons, respond and serve…Don’t complain about the verdicts that juries bring in if you won’t answer the call.”

Though detractors have accused Clark of being overly judgmental of others—ironic, given the scapegoating she suffered in the trial’s wake—she is equally critical of herself, both on personal and professional levels. Countering those who championed her as a role model, she reminds readers of her two failed marriages and a bevy of undesirable habits, including drinking (Glenlivet), smoking (Dunhills), and swearing like a sailor. In terms of her performance during the trial, Clark cites a “failure of nerve” for what she considers her “most painful regret”: not appealing Ito’s decision to allow evidence of Fuhrman’s past racism into the trial to a higher court. She also acknowledges over-zealous cross-examination of defense witnesses, downplaying domestic violence, a bone-tiredness that plagued her during the trial’s waning months, and an overriding sense of responsibility for any errors made by her team, either singularly or collectively. “I felt such guilt. I felt like I’d let everyone down,” she confides. “The Goldmans. The Browns. My team. The country.”

One thing that sets Without a Doubt apart from the plethora of other books on the topic is Clark’s voice, which, despite the contributions of a co-author, shines through from a truly scathing Prologue to a more subdued Postscript. Whether or not you agree with her, you can’t help but appreciate her candor and refusal to prevaricate.

The narrative itself is not entirely linear; rather, Clark—who first intended to reveal nothing of her private life, but later relented (“So many absurd things have been published about me that I feel I owe you an honest accounting of myself. By ‘honest,’ I do not mean exhaustive.”)—shares intimate details as they become relatable to the case. These include a tumultuous first marriage to an Israeli backgammon player and a sexual assault just prior to her seventeenth birthday—nearly the same age that Nicole was when she met Simpson—that allowed her to empathize with an otherwise distant victim. Though such details make Clark unnecessarily vulnerable, they also serve to bolster her credibility as a voice for righteousness.

Without a Doubt is an exhaustive, emotionally engaging account of Clark’s work on the case as well as the conflicts that plagued her: a bitter custody battle, harassment by the news media, critiques of her hair and hemlines, and chronic illness and fatigue. (Brief transcripts from car tapes that Clark recorded throughout the ordeal painfully illustrate both her utter humanness and the ever-growing depths of her despair.) The reader is left feeling nearly as emotionally battered as the author herself, who came away from the trial with the sense that she’d survived something akin to the wreckage of a 747. But, despite an initial loss of faith in the very system that she’d devoted her career to, Clark had a moment of reckoning: “Justice, like the will of God, doesn’t always manifest itself on the spur of the moment. It doesn’t always come when you think it should. You just gotta wait it out.”

Much like the divisive acquittal of O.J. Simpson, the verdict on Marcia Clark has been hotly debated for twenty-plus years. Regardless of the relentless ebb and flow of public opinion, one thing remains certain: She never lacked conviction—or a certain clarity that is only now beginning to resonate with mainstream America. The accompanying sense of understanding is its own kind of justice, and Clark deserves at least that.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

John Valeri wrote the popular Hartford Books Examiner column for Examiner.com from 2009 – 2016. He can be found online at www.johnbvaleri.com and will be featured in the Halloween-themed anthology Tricks and Treats, due out from Books & Boos Press in the fall of 2016.

Late in the evening of 5 September, Ruche Mittal and her husband, Manish, realised that there was trouble brewing.