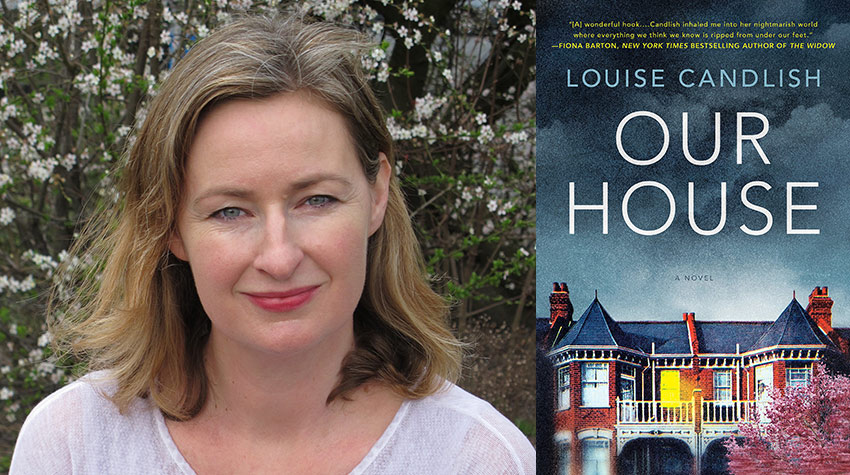

Q&A with Louise Candlish, Author of Our House

By Louise Candlish

August 9, 2018

In Louise Candlish’s new novel, Our House, protagonist Fiona Lawson returns to her posh suburban London home on a Friday morning in January only to find a curious scene. A moving van is parked outside. And inside? Another family, eager to finish moving in and start setting up their new home. Except, Fiona insists, she didn’t sell the house.

“This was always a cautionary tale,” Candlish says of the book. A bestselling author in the U.K., Candlish makes her U.S. debut with Our House on Aug. 7. As London property values climb ever higher, Candlish says she worries that people think of their houses more as multimillion-dollar assets to be cashed in and less as, well, homes. And when big money is involved, shady criminals can’t be far behind.

Our House finds Fiona Lawson in such a trap. She and her husband, Bram, have owned their home on Trinity Avenue for years, and its skyrocketing value has made them accidental millionaires. But their lives are in transition. After catching Bram with another woman in their kids’ backyard playhouse, Fiona wants to separate. But the housing market and the kids nudge the couple into a unique arrangement: they rent a nearby apartment and trade off nights at the house with the children.

Bram, however, is keeping secrets of his own, and the betrayal that began in the playhouse soon moves into the real house. Told from both Fiona’s point of view—via an appearance on a true crime podcast called The Victim—and Bram’s perspective, Our House is a twisty slice of domestic noir spiked with contemporary cybercrime.

Candlish, who lives in South London (a “less fashionable and a bit more edgy” part of the city than Trinity Avenue, she says), recently answered questions about her inspiration for the book, “Friday afternoon fraud,” and her favorite podcasts. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

As you began writing, what came first: the crime or the characters? What inspired the book?

It was the crime that definitely came first. The characters grew up around it. I was really interested in a couple of things that have to do with property in the U.K. and the fact the whole population seems to have become property obsessed. Properties have become overvalued, and people have become these accidental millionaires living in fairly average houses. At the same time, a whole terrible industry of property fraud has grown up. I really wanted to write about a crime that I hadn’t read about before in fiction, and I’d read about one instance in particular of criminals trying to steal someone’s house. They were a kind of faceless criminal gang, but I thought it would be far more interesting a novel if the criminal was someone who the victim actually knew. And then I started to think of a married couple—a separating couple—and the circumstances that would put them in a position where one of them was vulnerable to the other’s criminal activities.

As you researched property crime, were you surprised at how achievable a scheme like this is?

I was shocked. First of all, as soon as I identified this as crime, I wanted to put it at the heart of my story. So I read about it as much as I could. It was about a couple years ago when I started to research and write, and there wasn’t a whole lot of official research and guidelines. Those have come out more recently. At the end of last year—long after I’d finished my final draft—the Land Registry, which is the government arm that registers all property sales here, and the Law Society, which is the major legal body, collaborated on some extensive guidelines for property lawyers. Those guidelines are fascinating and would have been useful had they been available when I was writing.

I was pulling all the news stories, looking at statistics, and looking at the data, and I was absolutely shocked at how quickly property crime is taking off. Although, it shouldn’t be surprising. Property is a very high-value asset, and wherever you have high-value assets, you’re going to attract the attention of criminals who want to get their hands on it. Here, property-related cybercrimes are called “Friday afternoon fraud” because most property purchases tend to close on Fridays. The major crime is when criminals get the buyer to transfer their payment to the criminal account—and it’s now the biggest area of cybercrime in the legal sector. I was just blown away; I thought I had discovered something quite niche and minor, and it turns out it’s huge.

When people talk about homes, they tend to talk about big ideas: family, comfort, belonging. Apart from the actual taking of Fiona’s house, there’s a thread of housing anxiety running through the book—anxiety about property values, parking, neighbors, downsizing, selling, and buying. Can you talk a little about why the characters in Our House think and talk about their homes in these terms?

When people talk about homes, they tend to talk about big ideas: family, comfort, belonging. Apart from the actual taking of Fiona’s house, there’s a thread of housing anxiety running through the book—anxiety about property values, parking, neighbors, downsizing, selling, and buying. Can you talk a little about why the characters in Our House think and talk about their homes in these terms?

That was what I was interested in exploring. To me, this was always a cautionary tale. It’s possibly a little bit exaggerated, but not much so when I think about the conversations I eavesdrop on in cafes and the conversations my friends have.

In the last 20 years in London, homes have been discussed as property rather than in terms of “home,” and one of the reasons I wanted to write Our House is that I felt worried. We’ve very quickly and quite dangerously started to make decisions based on what a house is worth rather than other things, like “Should we move because it’s good for the children,” or “Should I move because I’ve had a great job offer.” All the decisions seem to center on how much the house is worth and whether it’s the optimum time to cash in this asset. There’s a line early in the book where Fiona says that if she had her time again, she’d concentrate a lot less on house and more on the people in it, and that’s my message in a nutshell. I think we’re all in danger of getting to the end of our lives and finding we spent a vast majority of it looking at house prices on property websites rather than reading Anna Karenina.

Social media and podcasts have become popular forums for working out true crime tales. Why did you decide to situate the narrative in these media?

Without giving away any spoilers, Fiona needed a forum for telling her story that would reach a lot of people quite quickly and be quite persuasive. From a writer’s point of view, I wanted to try something different. But at the same time, I didn’t want it to just be fun for me to experiment. I wanted it to be integral to the plot. It seemed that her doing an audio interview was the perfect way for her to tell her story; she’s in control of it, and she knows who the audience is because she used to be a member of the audience listening to this podcast called The Victim. It’s about gaining the trust of the audience and getting intimate. I listen to a lot of audio, and I always feel like I have such a direct and personal relationship with the speaker. I thought it would be perfect for Fiona’s story because, again, not to use spoilers, she has an agenda of her own.

Do you have any favorite podcasts?

Like everyone else, I love Serial. I remember the whole fever that gripped us all. I do love You Must Remember This, the podcast about old Hollywood. I think it’s so fantastic, and it has that very intimate, conversational tone I find to be very beguiling. I love radio plays. I listen to audiobooks a lot, but I listen to dramatizations of books and radio plays, usually in the dead of night when I have insomnia.

Check out our new true crime podcast, Case Closed!

The shifting perspectives you use are interesting: both Fiona and Bram are unreliable and with their own agendas. How did you decide on this approach? Was it apparent from the beginning, or did it assert itself while you were writing?

The whole novel was very plotted and deliberate and considered. I would say that I don’t consider Bram unreliable at all. He’s absolutely telling the truth as he sees it. He’s not withholding anything. Fiona is obviously less reliable. I was also very keen on having her tell the truth pretty much 99.9 percent of the time, so she tells a couple little white lies in her account on the podcast but nothing significant. What she’s doing is withholding important stuff. So she’s unreliable in that respect. But both of them are actually telling the truth as they say it.

Though the story belongs to Fiona, Bram, the charming villain that he is, frequently takes over the narrative. In the end, I couldn’t help but have some sympathy for him. Did you find your own feelings for the characters changing as you wrote?

Yes, certainly. I also became charmed by Bram and started to enjoy writing his sections more than I enjoyed writing Fiona’s. I wasn’t really expecting that. But there was a practical element worth mentioning. My editor at Berkley, Danielle, was very thorough in her editing of Bram the character. He was a little nastier, a little more of a philanderer, and a little less sympathetic when she first got her hands on him. Between us, we tempered him so it would be possible to see how he could be charming. He’s very candid and very honest, and I think that’s quite likable.

In the last 20 years in London, homes have been discussed as property rather than in terms of “home,” and one of the reasons I wanted to write Our House is that I felt worried.

The other thing about Bram that caused me to become more and more sympathetic as I wrote was uncovering these quite complex links between mental health and crime. He’s not acting the way he’s acting as a lifestyle choice; he’s really suffering. There’s a lot of despair, and he’s making decisions a sane and steady person wouldn’t make and allowing them to lead into the next bad decision. My original title was The Victim. Fiona’s the real victim, but I always felt Bram was a victim in his own way as well. It was never a black-and-white situation at all.

Our House has shades of noir, particularly the circumstances around Bram’s various misdeeds, and a sort of reverse-Agatha Christie kind of plotting—less of a whodunit and more of a why/how-dunnit. Which other crime/mystery authors/directors/artists influence you? Any particular favorites?

Agatha Christie would be my favorite. While I was not directly stealing from her, I had read everything she’d written in a very formative time in my life (my early teens), and I’ve always enjoyed the puzzle of a crime or mystery story. I definitely got that from her.

In terms of characters, when I was writing this book, I watched a whole sort of season of Barbara Stanwyck movies, and I’m sure an element of those have come through. Double Indemnity and those movies—where a simple crime always led to a crime that covers up a crime that covers up the crime before—influenced my writing.

Are you at work on your next book?

I am. I’m just finishing it, or I believe I’m just finishing it, but no doubt it will come back to me for a few more drafts. It’s another one I would describe as suburban noir. It’s about a street not unlike Trinity Avenue, where a neighbor has moved in and proved himself to be so ghastly and unpleasant and uncooperative with the residents that they soon find themselves accused of plotting to kill him. I’ve really enjoyed it. I tried to keep it simpler than Our House, which kind of broke my brain a bit, it was so complex. But it’s probably not that simple.