Page to Screen: Daphne du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel

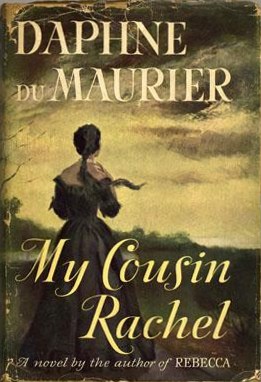

Daphne du Maurier’s novel My Cousin Rachel is a study in character ambiguity. Published in 1951, it takes place—not unlike her earlier Rebecca (1938)—on a sprawling estate in the author’s beloved Cornwall. Du Maurier again works in the mystery-romance mode, and to a large degree, My Cousin Rachel inverts her most famous novel’s premise. Rebecca charts the relationship between a young, inexperienced woman with the older man she marries. She does not know him well when they marry, and it turns out he has a good bit of mystery and baggage in his past. He is remote and difficult to connect with. The younger woman, quite earnest, tells the story, and she spends the novel trying to figure out the enigmatic personalities of the people she lives with, her husband’s included.

My Cousin Rachel is narrated by a naïve young man named Philip who admits to his house and falls in love with his cousin’s widow. She is 10-15 years older than him, and again, we have a story of one person, immature, who tries to understand the complexities of an elder they’re drawn to. Here, it’s the man narrating the novel, and there’s a fascinating dichotomy between what he tells us and what du Maurier, through her manipulation of his perceptions, tells us. This is one of those books where the novelist and reader see more than the narrator sees. It’s du Maurier’s great skill that makes it possible for her to do this, and what unfolds is a compelling tale about a relationship built on suspicion and shifting power relations. Daphne du Maurier expressed frustration that critics thought Rebecca a mere romantic potboiler rather than the study of a relationship between a powerful man and a woman without power. My Cousin Rachel explores a similar psychic terrain, except that in this case, it’s the man who lacks the power and the woman who has it.

Philip inhabits an odd space. He dominates the narrative since he’s telling it, but he never has command over his life. Orphaned as a young child, he grows up in the care of his cousin Ambrose, the man who owns and runs their estate and who seems to have no liking for women. What Ambrose imparts to Philip about women can be summed up by something he says to him when Philip is seven. He conducts Philip to a spot where a murderer has been left to hang for a number of days, according to the period’s custom. Philip explains that “Ambrose must have taken me there for a purpose, perhaps to test my nerve, to see if I would run away, or laugh, or cry. As my guardian, father, brother, counsellor, as in fact my whole world, he was forever testing me.” Ambrose has curious words for the boy about emotion and the dangers it can lead one into, saying, “See what a moment of passion can bring upon a fellow … Here is Tom Jenkyn, honest and dull, except when he drank too much. It’s true his wife was a scold, but that was no excuse to kill her. If we killed women for their tongues, all men would be murderers.”

He seems to be trying to raise Philip to be tough inside, manly one might say, and there’s a disdain for women in his voice. Their household has no women (even all their servants are men), and Ambrose has no romantic inclinations. Neither does Philip, who goes to Harrow and then Oxford yet makes no reference to having had girlfriends. When his school days end, Philip returns to their estate, and he settles in for what he expects will be many years there with his cousin, the two of them running the place without the distractions and “mischief” that come with having a female around. Imagine the consternation Philip feels when everything he thinks he knows about his cousin changes. Ordered by doctors to leave England and go to a sunny place for the winters, Ambrose obeys, and for the third winter—after previous trips to the Mediterranean—he decides on Italy. In Florence, as his letters home reveal, he meets a woman named Rachel, and soon the missives tell Philip something he can’t believe: his adored cousin has fallen in love. Even worse, he will not be returning home in the spring, as he has every other year he went abroad.

Philip will never see Ambrose alive again, and the sporadic letters Ambrose sends Philip indicate he may be weakening from something other than natural causes. By the time a desperate Philip goes to Florence to see what is going on, Ambrose is dead and Rachel has disappeared. Her villa is empty, looked after by servants. The man who Philip considered a model on how to live a sober, responsible, masculine life has departed this earth for good, and his undoing, as Philip sees it, was a woman.

The stage is set for everything that follows, the majority of the novel. Rachel announces herself to Philip with a letter, comes to live at his estate, and a complicated relationship develops between them. Since Ambrose has left everything he has to Philip, not to his wife, Rachel arrives almost as a supplicant. She has no friends or allies in England. And since Philip, convinced she killed his cousin, hates her before he has even met her, he is determined to inflict on the isolated Rachel any discomfort he can. He vows to be as inhospitable as someone of his class can be.

Is Rachel being flirtatious with Philip as she ignores his initial rudeness and makes jokes with him? Are her warmth and spontaneity natural to her, or is it an act to wrap him around her finger? With everything told from Philip’s point of view, the reader—like Philip—can never be sure, and it’s this constant incertitude from which the novel derives much of its suspense. Philip’s emotional state fluctuates daily from hope to anger to joy to disappointment to hope again. There’s a dry, ironic comic quality here—a quality the reader gets but that Philip does not: the guy who once was resolutely anti-women is portrayed in a way typically reserved for female characters. Page after page, in minute detail, he tells us how he feels. While he fluctuates in his moods, Rachel seems in control of her emotions, and because of this, she tends to have the upper hand in their interactions. She usually leads; he reacts. Power here comes from self-knowledge and internal strength, not from who controls the wealth.

Du Maurier’s novel, though plotted with her usual precision, is chiefly a psychological one, and capturing the nuances it presents, the ambiguity, has been the challenge facing the filmmakers who’ve adapted it. Twice My Cousin Rachel has been made into a movie. But does either version do the book justice?

The 1952 film, directed by Henry Koster, stars Richard Burton as Philip and Olivia de Havilland as Rachel. Twentieth Century Fox hired George Cukor to direct, but neither he nor du Maurier liked the screenplay they saw, and Cukor quit the project. Journeyman Kostler took over, working from the Nunnally Johnson script, and he does deliver a film that follows the book’s story well enough. Lots of dialogue is lifted verbatim from the novel’s pages, and the atmosphere is effective. Shots of the real Cornwall, craggy and dank, help. Yet at its core, Rachel herself, the film lacks something. Olivia de Havilland doesn’t have the illusive air of the novel’s character. She has little of the mystery the book’s Rachel has, showing an exterior mostly calm and pleasant without the turns between kind and cold that torment Philip. Richard Burton fares better, portraying the character’s lord of the manor ruggedness well, but we don’t get that clear a sense of his mental gyrations, the ambivalence toward Rachel that he cannot shake. His transformation from Rachel-hater to man-attracted-to-her, giving her a passionate kiss, feels too quick. Du Maurier in this novel, as in Rebecca, spins a story that is a masterful slow burn, and it requires a talented director to establish that pacing, deliberate but never slack, in a movie. Alfred Hitchcock, a storyteller the equal of du Maurier, is able to pull it off in his film version of Rebecca, taking his time and building suspense. That film clocks in at 2 hours and 10 minutes. Koster’s My Cousin Rachel has a running time of 1 hour and 38 minutes, but it really should be longer. Du Maurier’s plot needs time to simmer before it hits boil.

The 2017 adaptation is an improvement. It has lush photography and Cornwallian mood to spare. Rachel Weisz embodies the mysteriousness of the character, and though she has the appropriate restraint for a woman of her time, she brings more of a sexual presence to the role than de Havilland does. This hews to the book and helps makes Philip’s change from hostile to infatuated entirely believable. Sam Claflin is good throughout as Philip, his anger toward Rachel palpable in the movie’s early sections. He also happens to have a quality Richard Burton—marvelous actor though he is—does not: Claflin seems virginal at the start. Without evidence to the contrary from du Maurier, the reader of the novel suspects that Philip never once has had sex at the point Rachel enters his life, and surely one reason he falls for her as hard as he does is because he wants her physically. Rachel is attractive, pure and simple. The sex scene that is so important in the book is one thing this film version gets right; the act is consensual and a momentous one for Philip. He assumes it has cemented their relationship and that marriage must follow. The twist, though, is that Rachel becomes aloof toward him afterward, though it’s obvious she had no problems with the sex. She did it to thank him for something he gave her. Beyond that, their sex had no significance for her, and Philip is crushed. Again, if one is looking at conventional gender behavior in fiction, he’s like the young ingénue. He is the woman who gives her body to a man only to realize he didn’t love her, and Weisz and Claflin replicate this role-reversal component of du Maurier’s book perfectly.

Though the recent version runs only seven minutes longer than the 1952 film, its pacing feels more like the book’s. This might be because of the screen time director Roger Michell gives secondary characters, who barely register in the first movie. Philip’s old servant Seecombe, his financial guardian Kendall, and Kendall’s daughter Louise (the enigmatic Italian Rainaldi)—all are important in the book and vivid presences in the 2017 film. They add color and layering; in effect, their contributions slow down and enrich the narrative, which helps the tension grow. The film doesn’t grip you with the steel hand du Maurier holds you in, but it does a respectable job at tackling an author who, as a “mistress of calculated irresolution” (Kate Kellaway, The Observer, 15 April 2007), is no easy writer to adapt.