At the start of my new novel, The Breaking of Liam Glass, a desperate young journalist named Jason pitches a story to a tabloid about a teenage footballer he came across who was stabbed and is in a coma. Unfortunately, the tabloid wants more of a celebrity hook to the story—a hook he doesn’t know if he can provide. And so Jason is led, step by step, into the dark and dangerous world of fake news.

The story is fiction—a satire—but behind it is fact. There has been a flood of innocent knife victims, especially here in London, and we are increasingly inundated with fake news. The whole point of fake news is to change things, and there’s nothing new about it. It goes back as long as people have been writing, it’s often criminal, and the tabloids have certainly served up their fair share.

It’s sometimes called propaganda, sometimes psy-ops. These are just different ways of saying “lies.”

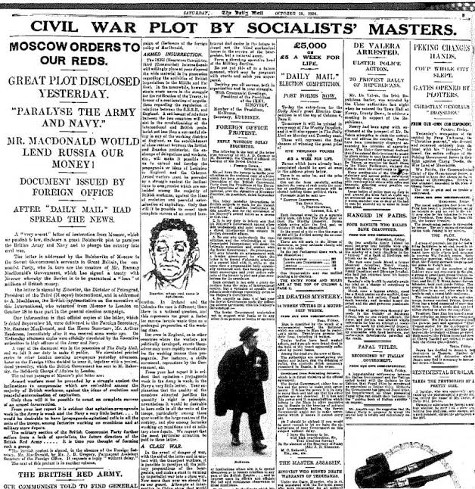

Over ninety years ago, just days before the general election of 1924, The Daily Mail published the Zinoviev Letter, supposedly written by Russian communists. It appeared to show that Labour’s attempts to establish diplomatic relations with Moscow would lead to the overthrow of democracy. Despite being a forgery, it sank Labour’s chances of winning and led to a Conservative landslide.

More recently, of course, we saw Tony Blair’s “dodgy dossier.”

Even internet fake news isn’t new. Long before Google, I wrote the Internet Search FAQ to help people search the internet more effectively, pointing to useful parts of the net that few writers know about, even now. I soon realized I also needed to help surfers distinguish the sites they could trust from those they could not. It covered issues such as checking how often the site was updated and looking for internal contradictions or sloppy language. (You can read it at www.search-faq.com).

Of course, social media has only added to the problem.

Few people have the time to check their sources in the way that newspapers, TV, and radio can (or at least should). And many of us are only too happy to repeat juicy nuggets that happen to coincide with our beliefs without caring too much if they are true or not.

The result we can see is rising anxieties, tensions, and aggression; it’s impossible not to believe that aggressive behavior doesn’t affect people. And while I personally believe that there aren’t any more aggressive and unpleasant people around than in earlier ages, social media hands them a megaphone, so it’s easy to start to think they are the majority.

Which brings us to knife crime.

What’s so shocking about knife crime today is not the violence. We actually live in the least violent times in human history. Even if you include the horrors of today’s war zones, fewer people are dying violent deaths across the world, and in Britain that number is tiny.

What’s shocking, though, is the randomness and stupidity. Take Ben Kinsella, stabbed eleven times in five seconds after a friend had an argument in which Ben had not even been involved. There was Frederick Moody, killed after a water pistol fight. Then, there was Elliot Guy, knifed at a party by a man he’d never met. Twenty-one deaths in London in a single year, over 200 across England and Wales.

There’s no obvious pattern, and the innocent dead include black and white, as do their killers. Surely, anyone would want to do something about it.

Enter the tabloids.

I grew up with tabloids. My parents wouldn’t have touched them, but when I stayed with my grandmother during school holiday, she took both the Mirror and the Express. I grew to love their energy, their accessibility—even their tangy, papery smell.

Tabloids have run campaigns that the broadsheets wouldn’t—and to great success. I spent some days researching Liam Glass at the Daily Mirror in their massive open-plan newsroom, and I was struck by the sight of enormous blow-up front-pages around the walls, each commemorating a memorable headline. Often, these were major campaigns.

Near the end of the novel, two otherwise cynical editors on my fictional tabloid (The Post) reminisce about the great campaigns of the past: “obesity and body image, postcode health, MPs for sale, rip-off trains, graduates who couldn’t spell.” They have much to be proud of. But the tabloids have also done far less honorable things: the smear campaigns, the racist slurs, the doorstepping of innocent people, and of course, phone hacking.

Jason finds that his teenage stab-victim will only hit the headlines if he fits the tabloid rules—celebrity, scandal, sex. So he sets out to see if he can adjust the story with just a few very small tweaks of the truth. Those few tweaks lead to a few more. And then a few more…

One crime leads to another.

Is it possible to have the energy and accessibility of the red-tops without the nastiness, the big campaigns without the invasions of privacy?

I don’t know. But I believe in satire. Satire speaks the truth. I learned the truth about newspapers from Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop, the truth about capitalism from Catch 22, and the truth about government from Yes, Minister and, later, The Thick of It.

Does satire change anything?

I always remember Peter Cook’s famous line about “those wonderful Berlin cabarets which did so much to prevent the rise of the Adolph Hitler and the Second World War…” And yet, we have an honorable duty to laugh at power. To expose those who exploit the vulnerable and show them with their pants down—metaphorically and literally.

And, pace Cook, every change, every revolution started when someone had an idea. The Berlin Wall, which looked so solid, collapsed in the end. And behind it, we found the truth—like the Wizard of Oz, not unbeatable but small and cowering.

That’s the real news.

Read an excerpt from The Breaking of Liam Glass!

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

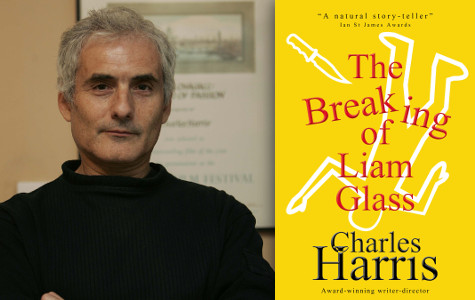

Charles Harris is an international award-winning writer-director and a highly-respected script consultant, writing and directing for cinema, television, and theater. He is also a bestselling non-fiction author with titles including A Complete Screenwriting Course, Police Slang, and Jaws in Space. Several of his short stories have been published, with two shortlisted for awards. Charles has a black belt in Aikido and teaches police, security personnel, and the public self-defense against street violence, including knife attacks.

thanks