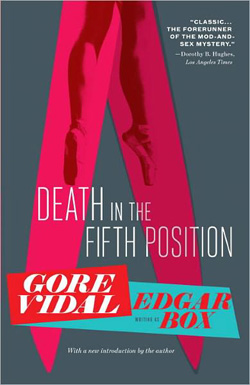

Gore Vidal made a moderate splash in literary circles with his first two novels, but the reaction to The City and the Pillar, in which he wrote about a young man who has a “Brokeback Mountain” moment with a high school classmate and becomes obsessed with recreating the passion he felt that night, almost undid that early sucess. Not only did The New York Times refuse to review it, but they wouldn’t mention anything else he wrote, either. (Vidal says he was dead to the review section for six years; the Times archives indicate it was four at most.) In the midst of his troubles, a savvy publishing executive took him out to lunch and suggested he pick a pseudonym and write some mysteries. The result was a batch of suave, urbane mystery novels that Vidal says sustained him financially throughout the 1950s until he could restore his literary reputation. The three books, out of print for decades, were reissued in paperback by Vintage a few months back, under a byline—“Gore Vidal writing as Edgar Box”—that formally confirms one of publishing’s biggest open secrets.

Gore Vidal made a moderate splash in literary circles with his first two novels, but the reaction to The City and the Pillar, in which he wrote about a young man who has a “Brokeback Mountain” moment with a high school classmate and becomes obsessed with recreating the passion he felt that night, almost undid that early sucess. Not only did The New York Times refuse to review it, but they wouldn’t mention anything else he wrote, either. (Vidal says he was dead to the review section for six years; the Times archives indicate it was four at most.) In the midst of his troubles, a savvy publishing executive took him out to lunch and suggested he pick a pseudonym and write some mysteries. The result was a batch of suave, urbane mystery novels that Vidal says sustained him financially throughout the 1950s until he could restore his literary reputation. The three books, out of print for decades, were reissued in paperback by Vintage a few months back, under a byline—“Gore Vidal writing as Edgar Box”—that formally confirms one of publishing’s biggest open secrets.

(Vidal’s authorship was acknowledged in one of the blurbs used on the dust jacket of an omnibus edition, Three by Box, back in the 1970s, and he’s discussed the circumstances behind the pseudonym several times, even before the introductions he wrote for these new editions. This is, however, the first time Vidal has allowed the books to be published under his own name.)

Peter Cutler Sargeant II is just 28 at the start of Box’s debut novel, Death in the Fifth Position, but he’s already fought in the Second World War, come home and earned a degree from Harvard, then served three years ghostwriting for an alcoholic New York theater critic. That’s until he goes the wrong way about asking for a raise and winds up having to launch his own PR agency. He’s just been hired by the head of a major dance company to fight off the potential bad publicity of having their new choreographer accused of being a Communist when the company’s star ballerina, Ella Sutton, meets with tragedy on opening night. The cable suspending her more than thirty feet in mid-air for the show’s climax breaks. Still, she goes out like a professional: “She maintained complete silence as she fell in fifth position onto the stage with a loud crash, still on beat.”

Vidal clearly has fun giving readers a backstage tour of the ballet world in all its bitchiness: Peter quickly discovers that everyone in the company, from the orchestra conductor to the Russian prima donna, had a good reason to hate Ella, and he manages to land in the gorgeous young understudy’s bed just hours after fending off an advance from the lead male dancer. He’s fairly blasé about the latter incident (welcome to show biz) but still capable of being shocked—if this isn’t the first trip an amateur sleuth makes to a gay bathhouse in popular mystery fiction, I’d like to read whoever beat Vidal to it. Unfortunately, the murders keep coming, and the thing is, they’re just so damn inconvenient, messing up both Peter’s job and his sex life:

I had to admit to myself that for all I cared the murderer could go free… I’m not a crusader or a reformer and I have no passion for justice: not the crazy way the world is now at least. Official murder, private murder… what’s the difference? Not much, except when you’re involved yourself or someone you care about is. The more I thought about it the sadder I got.

Eventually, after having one last conversation with all parties concerned, Peter puts all the clues together and unveils the killer—but he’s not particularly judgmental about the motives, just pleased with himself for solving the puzzle. Vidal would take the exact same approach to character and plot in Death Before Bedtime, shifting the scene to Washington, D.C’s intersection of politics and high society. This time, despite being hired by his old newspaper to provide eyewitness accounts of the ongoing investigation, Peter’s willing to let the murderer walk—“I have few sadistic impulses and I had no chivalrous love for any of the dead”—and decides to tell all only after the killer panics and tries to poison him.

Then it was off to the Hamptons for Death Likes It Hot, but the formula begins to wear thin. (Maybe the repetitiveness wasn’t quite so obvious if you read the novels months apart.) There’s a somewhat clever bit of misdirection with the first death, but all things considered, it’s probably best that Box retired when he did—although, as long as Vidal was sticking to the “write what you know” principle to choose his settings, a fourth novel with a Hollywood homicide might have been an entertaining diversion.

Finally, Vidal and Mcdonald both honed a smart, snappy prose style which allowed readers to flatter themselves that, like Peter and Fletch, they knew the real score. In fact, the most important lesson Vidal might have learned trying to write “stupid” commercial fiction is just how much sophistication (subversion, even) you can pack into plain language. Some critics might suggest that it would take a while for Vidal’s own fiction to show off his caustic, satirical voice as effectively as Edgar Box did.

Ron Hogan is the founding curator of Beatrice.com, one of the first websites to focus on books and authors. He is a contributing reviewer at Shelf Awareness and covers the literary world for USA’s Character Approved blog.