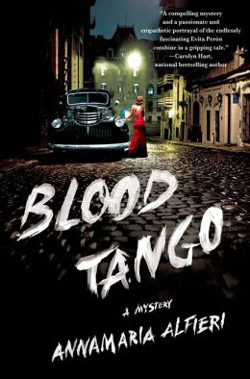

An excerpt of Blood Tango, a historical international mystery by Annamaria Alfieri that takes place during Juan Perón's leadership of Argentina (available June 25, 2013).

An excerpt of Blood Tango, a historical international mystery by Annamaria Alfieri that takes place during Juan Perón's leadership of Argentina (available June 25, 2013).

It is the most dramatic and tumultuous period in Argentina’s history. Colonel Juan Perón, who had been the most powerful and the most hated man in the country, has been forced out of power. Many people fear that his mistress, radio actress Evita Duarte, will use her skill at swaying the masses to restore him to office. When an obscure young woman is brutally murdered, police detective Roberto Leary concludes that the murderer mistook the girl for Evita, the intended target of someone out to eliminate the popular star from the political scene.

The search for the killer soon involves the murdered girl’s employer, who is Evita’s dressmaker; her journalist lover; and Pilar, a seamstress in the dress shop and a tango dancer. The suspects include a leftist union leader who considers Juan Perón a fascist and a young lieutenant who feels Perón has dishonored the army. Their stories collide in this thrilling and sensuous historical mystery.

Chapter 1

Wednesday, October 10

Trouble was closing in on Buenos Aires—like a huge jaguar charging toward the coast from the vast interior plain of the Pampas, with blood in its eyes and mayhem in its heart.

On that day of the 10th, thousands of people made their way to the center of the most elegant capital in all of South America. Their goal: a rally at the intersection of Alsina and Perú, where nineteenth-century buildings of scale and grace had earned the city its sobriquet—Paris of the South.

Among the throngs were six—three women and three men—whose futures hung in the balance. Two were obscure girls, oblivious to the scent of the approaching beast. Two young men, with axes to grind, felt the giant cat coming and feared it. Evita Duarte prayed it would be an angel bearing gifts; she opened her heart as it neared. Juan Perón imagined he himself might embody its power and decide the fate of the nation.

On that cloudy afternoon in spring, Argentina’s destiny was ripe for the picking. No one was happy with the government, not even the men who were running it. The country’s divided citizenry had never chosen sides in the worldwide conflict just ended in Europe and Japan. The upper classes, who spoke Spanish but otherwise comported themselves like British aristocracy, had favored the Allies. The Axis-leaning generals of the military regime had no idea how to maintain their power after having backed the wrong horse in World War II. Every move made by either side—the army or the clamoring populace—merely increased the level of national dissatisfaction and confusion.

Turmoil had stalked the nation for over two years. Now chaos prowled ever nearer and threatened to grab Buenos Aires by the throat. It would take a week before the crisis played out and Argentina’s destiny was sealed.

The event, which drew fifteen thousand, began as a seemingly innocuous occasion: a farewell rally to see off Juan Domingo Perón. Until the day before, Perón had been the most powerful, and therefore the most hated, man in Argentina: its vice president, minister of war, and secretary of labor. The populace massing in the plazas and storming along the avenidas had demanded his fall from grace. Finally, a reluctant President-General Edelmiro Fárrell deposed Perón. Many in the army hierarchy imagined that this sop to the protestors would actually save the day.

Colonel Perón, less put out than one would have imagined, approached the rally in the backseat of a chauffeur-driven, gleaming black Packard touring car; the speech he was about to give lay in his lap. He gazed out at the blooming jacarandas along the streets, the Beaux Arts apartment buildings, the leafy parks as they passed. He felt the jaguar nearing. Soon he would either become one with it, or it would bloody his dreams and devour his future.

The tiny, pensive woman next to him on the plush leather seat, his mistress, the radio soap opera actress Evita Duarte, held his hand and stared out the opposite window but took no notice of the elegant architecture and fancy restaurants. She clenched her teeth on her bottom lip.

Perón was angry with her. At home that morning, she had stamped and stormed over her colonel’s loss of might. She wanted to keep quiet now, but her outrage threatened to boil over, again.

When General Avalos had come to their apartment, as President Fárrell’s emissary, to demand Perón’s resignation, she had tongue-lashed the miserable bastard. Insulting words had flown out of her mouth. Avalos had stared, stupefied, as if he had been scolded by a lapdog. Perón had not berated her for that outburst, merely raised his eyebrows. But she was sure he had been extremely displeased. She had gone too far.

She let go of Perón’s hand and tugged the hem of her tweed skirt toward her knees. “Avalos calls himself the commander of a garrison? He’s a stuffed cuckoo. He looked like a gnome standing next to you. If that parley in our living room had been a scene in a movie, everyone watching would have seen you as the tall, handsome hero and him as a squat dope, without brains or cojones. I don’t know how you keep your temper with them, Juan. Why are you so calm?” She bit her lip again.

Perón took her little hand back into his and squeezed it hard. It did not seem to either of them purely an act of affection. He considered her. With her enormous power to sway ordinary people, she might help him regain his position, but her passion would be useful only if she contained and he directed it. Otherwise, her impulsiveness would destroy his balance as he walked a tightrope back to the seat of government. Everything depended on the purity of her belief in him. He had to be careful which of her strings he pulled. Best to keep her off balance for now: insecure enough to remain on the sidelines but sure enough of him to stay close and be ready to help when he wanted her. What a dance he had to perform to keep her within bounds. But if it worked, she would be worth it.

He reached into the left breast pocket of his suit jacket and took out a package of Gauloises and the gold cigarette holder his men at the War Ministry had given him for his fiftieth birthday. That was only two days ago—when he had still controlled the most important parts of the regime, including the president himself. Not anymore. Perhaps never again. He held the trinket out in the palm of his hand. “This may be the last such gift I receive,” he said.

“You are tired,” she said.

“I am discouraged.” He gave her a regretful smile. “You are young. When you are young and tired, you feel tired. When you are old and tired, you feel old.”

“You are not old,” she said, though his age was just under double hers. “Perhaps you should take some time to rest.”

“I think I need a permanent rest.” The words were out of his mouth before he considered whether they would move her toward being more useful or less.

She took in her breath in alarm and looked at him in shock. Her heart skipped a beat.

“No, no.” He waved his hand as if to erase what he had spoken. “I don’t mean giving up on life. But we could go away, live quietly together, and not have to contend with all this turmoil. To Uruguay. To Paris, even, now that the war is over. We could have a nice time, just the two of us.” He knew the image was a fantasy, a pretty picture he would never truly inhabit. It could, however, be a prize he dangled, a carrot to get her to control her temper. He watched her eyes in the rearview mirror in the center of the windshield. He could not tell if she was taking the bait. He put the cigarettes and holder back in his pocket without lighting up.

Evita heard longing in his voice. He spoke of a life for them together. She wanted that. She needed him. More than he needed her. Where would she go if she lost him? And where would her future go if he lost out? She wanted the safety a man of power could give. She deserved it after all she had suffered. “Will you abandon the poor workers?”

He patted the yellow foolscap pages of the speech on his lap. “I have one more gift to give them today. After this, I may be beyond helping them.”

She almost called him a coward. She wanted to see him fight like a tiger. For his position. For what he could do for the poor. “What will those boys down in the slaughterhouses do without you to be their champion?”

He smiled. Her power would come from this anger at injustice. For now, he must kindle the flame without letting loose its fury—keep her off balance and tip her in the right direction when the time came. Like firing an artillery shot when the enemy was close enough to die. “If I have the poor workers’ complete support, perhaps I will have the future we all want. Sometimes I think no one can destroy me if they are on my side.”

She searched his eyes in the reflection for a clue to what he wanted her to say. She felt danger in the touch of their hands. If she pushed him too far, he would throw her over. She was not his wife. One word from him and she would be gone.

They never talked of marriage; they both knew why: as long as he needed the support of his so-called superiors, he could never marry such a wife: a common actress, especially an illegitimate child like herself. But she spoke about her origins to no one—especially not to him. For over a year now, he had defied the army’s stuck-up morality and lived openly with her. She knew his fellow officers despised him for it. “Those army snobs have forced you out because of me. It’s true, isn’t it?” She bit her lip, as usual after she had said entirely the wrong thing.

He patted her knee. It was like her to think she was the reason for everything that happened, but in this case she was more than half right. True, everyone in the country seemed to have one reason or another to get rid of him. The upper classes because he pushed through laws forcing them to pay their workers more. The crowds in the streets blamed the army for imposing the state of siege and suspending the constitution. They singled him out as the most visible symbol of military rule. The worst fools insisted he was a Nazi. How could he be a Nazi? He did not have a single drop of German blood in his body. Those who called him one were a bunch of communists. He sighed. All that was true, but his enemies focused more on her than on anything else about him. Which could be good as well as bad.

She shifted in her seat as the car turned south toward the center. His silence made her nervous. “Those disgusting vultures who oppose you,” she said. “They deserve to be horsewhipped. Even a horse deserves better treatment than they do.” She fingered the oversize ring on her right hand. She wanted the chance to seduce crowds for him, make them gather in the plazas and chant his name. She had talked on the radio about his greatness, but no woman could take a platform in public, especially a woman who was his mistress, not his wife.

He kissed the back of her hand. She was puzzled, off balance. Which was where he wanted her. For now.

* * *

While Perón’s Packard left the sycamore-lined streets of the Barrio Norte and entered the commercial district, Lieutenant Ramón Ybarra, handsome and elegant in civilian clothes, carried his hatred to the rally by underground train. As he exited the Subte’s A Line at the Perú Street stop, he looked up approvingly at the gray skies, so fitting for the mood of the nation. He wished he could draw a downpour from those clouds to wash out Perón’s speech or, better yet, a lightning bolt to strike down both him and his actress mistress.

Ybarra had come to watch, firsthand, the next act in the drama that threatened to plunge the country into chaos. Earlier he had left the Palacio Paz, the army’s headquarters in Buenos Aires and supposedly the center of its power, but these days the mahogany-paneled rooms seemed to Ybarra more like a dovecote for an emasculated flock of cowering pigeons. Over the past two years, his army superiors had allowed Colonel Juan Perón to dilute the army’s power and to aggrandize his own. Whoever heard of a military government that supported Bolshevik labor unions? What the fuck had happened to the army’s campaign for public morality? Could the military demand that ordinary people stop acting like animals if the most powerful man in the service lived openly with a common actress?

The downward spiral of the nation had been troubling Ybarra for months. But while the country tottered on the edge of an abyss, the senior officers had stroked their mustaches, talked about trouble brewing but had done nothing to quell it. Now they had forced out Perón, but was he gone forever? On would he return with more might than before?

The scene around Ybarra increased his fears. The streets were packed. There were thousands here. Perón, the clever bastard, had put his farewell gathering at a spot easily reached by many. If the rabble decided to bring their outrage to the seat of government, they would have only a few blocks to march to the Casa Rosada: a pink palace. Not a proper color for a national headquarters, but it seemed to suit the current resident. President Edelmiro Fárrell was more interested in women and song than showing force and ruling Argentina.

Ybarra pulled down the brim of his hat to hide his identity. Making sure he would not be recognized was one of his main objectives this afternoon. The other was to get the goods on Eva Duarte, evidence that she would fight to restore Perón to power. After those shameless paeans to her lover that she broadcast over the radio, Ybarra was sure the puta would stop at nothing to make sure her sugar daddy had the connections to keep her in the sweet life.

The tall lieutenant in the civilian suit moved with the throng down Perú to where a platform had been erected, complete with microphones and decorated with blue and white bunting and Argentine flags. As if Perón were a patriot. It made Ybarra want to vomit.

Suddenly, he could have sworn he saw Perón’s mistress ahead of him in the crowd. Just there, a little blond in a straw hat. He was amazed. He had expected Evita to come, but he had imagined the little slut would arrive in Perón’s fancy car. What could she be doing out here with the mob, wearing a green dress, and chatting with another girl, acting like the common woman she was? He tried to get a closer look but failed to make any headway in the press of people jamming the intersection.

Keeping his eye on the spot where he had seen her, Ybarra settled for a place on the fringe of the crowd, among a bunch of unionists carrying signs that said WORKERS’ RIGHTS ARE HUMAN RIGHTS.

Why the bastard was being allowed to stage this farce was beyond understanding. The generals should have muzzled him, not given him a platform at government expense. And from the looks of the big square microphones and the heavy wires coming from them, Perón and his minions were going to broadcast whatever he said, so there would be no censoring him. This was a huge mistake.

Perón’s Packard pulled up across the intersection, and the colonel got out. He was tall enough to be seen over the heads of his cheering supporters. When an old man in an ill-fitting suit appeared on the platform and started to fiddle with the sound equipment, the mob began to chant, “Sindicato. Sindicato.” Others, not satisfied with praising their Trotskyite unions, took up the eminently chantable name of the son of a bitch who had raised their wages and used the business owners’ money to buy their love. “Perón. Perón.”

Ybarra craned his neck to see if he could catch sight again of the actress, but the crowd was too thick. As Perón mounted the stage, they surged forward, stamped their feet, and clapped their hands. “Perón, Perón.”

The man of the moment approached the microphones to tumultuous applause. The puta was not with him. That must have been her Ybarra had seen in the crowd. Someone had had the good sense to keep her in her place—in a manner of speaking. If she was really kept in her proper place, she would have been cleaning someone’s house. Or lying dead in a coffin.

The whole scene boiled Ybarra’s blood.

* * *

On the other side of the chanting crowd, an equally angry Tulio Puglisi was one of the unionists in the ranks, shouting, “Sindicato! Sindicato!” only to be drowned out by people he thought misguided at best. They called not for justice for workers but for one man only. “Perón. Perón.”

Too short to see over the masses, Tulio stood on the tips of his shoes—the best the leather workers of his union could produce—and fumed in his heart over this outpouring for a man he considered a devil.

At a ten-hour-long meeting of the various unions the day before, he had repeatedly begged the other officials to stand down from this circus, to wait until October 18, when they could organize a demonstration for something other than the power of Perón, Argentina’s prime fascist. Puglisi had dragged out every possible argument: reminded them that their Juancito Perón fell in love with Mussolini before the war started; that, like his fellow army officers, he loved the Germans.

Tulio’s friends had looked at him in horror. Many of them were cowed by the threat—present though not certain—that a person who spoke such thoughts could disappear and not be seen again. But Tulio’s family had resisted intimidation in Italy, and right here in Argentina during the war, they had stood up to the fascists who with their Nazi counterparts had prowled immigrant neighborhoods, trying to force Germans and Italians to support their dictator-heroes. He was his father’s son and no coward. What was it to be a leader if you refused to take a risk for what you believed?

The pro-Perón so-called unionists at that meeting had given him smug looks, as if they had his number. They countered his arguments with a laundry list of Perón’s “gifts” to the workers: better wages and working conditions, paid vacations, free health insurance. True, the colonel had arranged those benefits, but with only one purpose—to enthrall the most ignorant among the union members.

“This is our moment to stop the fascist,” Puglisi had declared, “while Perón is weakened. If we don’t seal his fate now, he will make sure we never get another chance.” The men around the table had looked away from him.

Finally, in desperation, he told them a secret he was not supposed to divulge. “My sister-in-law works for Bishop Coggiano. Perón is bringing in Nazis. She has seen them in the bishop’s palace. They are moving here in droves. It’s all controlled from the Vatican. German and Croat war criminals, using gold from the teeth of people they murdered to buy into our country. The bishop says we need them because they are anti-communist. Before we know it, the Fourth Reich will be ruling Argentina.”

A hush fell on the proceedings after that, but he could not change their minds. The more he begged, the less they listened.

After the meeting, Tulio’s cronies tried to gloss over the fact that he had said things that could get a man thrown in prison or worse. They slapped him on the back. “Oh, come on, Tulio,” they said. “Tomorrow is his farewell rally. You should be glad to say good-bye to him if you believe he is such a dangerous character.” Then they all disappeared, and he realized that even his closest allies were too afraid of what he had said even to drink a coffee with him.

Defiant in the face of intimidation, Puglisi had put on his best suit and shoes and come to this Perónist circus.

The platform his nemesis now mounted was festooned with blue and white bunting and Argentine flags flapping in the breeze on each corner, the colors of a country Tulio saw as doomed. Then he saw in the crowd Perón’s lady friend. She had been praising him on the airwaves as if he were some sort of deity. Puglisi believed she could become a key player in this real-life drama, but he knew what his fellow unionists would say if he brought up that subject—that no one would take a soap opera actress seriously.

But Tulio Puglisi knew in his bones that stopping Eva Duarte could very well be the key to saving Argentina from fascism. He felt as if he were the only person in the country who knew that.

* * *

Near that platform in the center of the intersection, Jorge Webber, Perón’s chauffeur, shadowed Evita. She was nervous today. She had spoken sharply to Perón in the backseat while Webber drove them. The colonel had left them in the car, saying Evita should stay inside the vehicle and telling Webber to keep her there with him. But as soon as Perón walked away, Evita got out of the car and ordered Webber not to accompany her. She spoke in that demanding way of hers. He held his tongue and followed her without her realizing it. He wondered how she could bear the stares of the people around her. Cranky as she was with him, he felt compelled to protect her. A few feet away from him now, she tapped her foot and looked at her red fingernails. He could tell she was trying not to bite her cuticles.

Over and over, people nearby recognized her and insisted on trying to talk to her. Their voices were mercifully drowned out by the sloganeering. Webber feared there were people here who hated her. He had heard what they called her behind her back. Sometimes he wondered that she seemed not to notice. It was his job to make sure they did not insult her.

* * *

Across the jammed street, near the cheering employees of the Secretariat of Labor, Luz Garmendia was delighted to have people try to talk to her. She smiled coyly at them and basked in their admiring glances, because they mistook her for the actress Eva Duarte. That she could pass for Evita had changed her life. Pride shone in the girl’s dark eyes. Today, more than any other of her life, she felt whole and happy. She had always tried to act cheerful, but until she met Evita she had been sad for as long as she could remember.

After her mother died, when she was four years old, she had lived alone with her father and his mother. If she had been strong like Evita, she would have told her grandmother how bad it was to constantly remind a child what a burden she was to her father. And if Luz really were Evita now, she would have her father arrested for the beatings he had given his little girl anytime she showed any spirit.

At fifteen, she had run away to live with Lázaro, a man she met in the market who smiled and promised to marry her. For the first month, he had petted her and told her she was beautiful. Then, he, too, began coming home drunk and smacking her around. One night he choked her while she slept; she woke up unable to scream. Not even her father had done anything that bad, but she had had nowhere else to go. If she really were Evita, she would have him arrested, too, for breaking his promise.

Luz’s life had been miserable until Señora Claudia, a dressmaker who lived in the apartment building where Lázaro worked as a gardener, had rescued her. That wonderful lady had found little Luz a room in a good woman’s house and had given her a job in her elegant shop on Florida Street. Luz had begun by cleaning, but before long she was taking out basting stitches and ironing dresses. The workshop was a paradise of colors and textures: blue, white, and silver brocade, soft fuchsia cashmere, thick tan English tweed, gossamer turquoise silk.

One day, Luz was unable to resist a black sheath gown she was pressing. It had a square neckline and slender skirt with a cunning slit at the front of the hemline that curved apart to reveal the lady’s shoes. The dress was lined with cream-colored satin. Alone in the shop, Luz had taken the garment into the dressing room and slipped it on. It felt like water on her skin. She put on the high heels that were kept for customers to use when trying on long dresses. The shoes were several sizes too big for Luz’s tiny feet. She shuffled out to the carpeted pedestal to see herself in the triple mirror. The gown looked as if it had been made for her. She had stared at her reflection and wondered what a girl would have to do for a man to catch one rich enough to buy her a dress like that.

At that moment Claudia Robles had opened the door and stepped into the fitting area. Luz let out a yelp, but she was frozen. She could not get off the pedestal and run away in the narrow skirt and flopping shoes. She burst into tears.

“No don’t,” Claudia called out. “Don’t let your tears drop onto the silk.” She grabbed a cloth from the bin where they threw the scraps and ran over to dry Luz’s eyes. Then she stepped back and appraised the girl in the splendid gown. “It fits perfectly,” she said. “You don’t have her face or hair, but your bodies are identical. Look how that gown fits you. Even the length is just right.”

“Who is it for?” Luz had asked.

“Evita.”

Like a word in a magic spell, the speaking of that name began Luz’s real life. For nearly five months now, rather than on a manikin, Señora Claudia had fitted all the actress’s clothing on Luz’s body. And she asked Luz to model for Evita and her sister and their friends when they came into the shop to pick up suits, day dresses, ball gowns, all the beautiful things an important woman needed. Evita said that rather than trying on the outfits herself, she preferred to watch Luz move in them. It gave her a better idea of the impression she made.

Evita was so kind. She taught Luz to walk and to sit like a lady in a play. And she gave Luz a large tip on each visit. Just a few days ago, she had given Luz the beautiful dress she had on at the rally today, an afternoon dress of spring-green lawn, with a narrow waist and a dirndl skirt that came just to the bottom of her knee, so that it showed the curve of her calf, but still looked demure. The buttons in a double row down the front were mother-of-pearl, the size of a one-peso coin. The short sleeves turned up in a cuff. Luz loved the way she looked in that dress here today with her now-blond hair, fixed in a style she had seen on the actress. Even her makeup—penciled eyebrows and bright red lipstick—matched what Evita always wore. Luz felt wonderful.

Earlier that morning, when she had met her friend Pilar, who worked with her in the dressmaker’s shop, Pilar had said, “You look like the daughter of one of those dandies who arrives on the Calle Florida in a chauffeur-driven car to shop at Harrods for riding boots.” But Luz knew better. She looked like Evita. And the glances of people around her confirmed that. She glowed with the conviction that many of those who stared at her thought she really was the lover of the man whose name they chanted, the beloved leader they were about to lose.

* * *

Pilar Borelli, Luz’s co-worker, scanned the people around them for a different reason. Her wary eyes sought signs of danger. As they left the Subte and made their way to the intersection of Alsina and Perú, Pilar had caught sight of Miguel Garmendia, Luz’s father, a man Pilar knew to be a threat to his sweet, star-struck daughter. Just the week before, Garmendia had come to the Club Gardel, where Pilar went to dance the tango. That night he had threatened to kill Luz.

By midnight on that Saturday, the Club Gardel had just gotten into full swing. The bar was packed with single guys eyeing the girls along the wall opposite. Though the dance floor took up most of the club’s space, it was inadequate for the number of couples. The denizens of the troubled city seemed to have turned to their music and their dance as the only possible comfort in the face of imminent chaos. The longing in the melodies, the nostalgic, sometimes bitter lyrics matched the mood of the moment in Buenos Aires.

As the strains of “Caminito” ended, the seamstress Pilar Borelli let go of the hand of Mariano, the singer everyone thought was her boyfriend. Often Mariano thought so himself, and sometimes she let him. Whenever he was not at the microphone he danced with her, and she seldom danced with anyone else though she hated the smell of the carnation he always wore in his buttonhole. He said it was his homage to the great tango singer, Carlos Gardel, but it reminded Pilar of her mother’s funeral.

Mariano climbed onto the bandstand, whispered into the ear of Luis, the bandoneón player, and adjusted the big round microphone. Pilar turned toward the bar and immediately caught the eye of a heavyset man of about fifty making his way toward her with a look that seemed to say he wanted to dance with her. He was unsteady on his feet, had had too much to drink. She turned away, toward the sanctuary of the ladies’ room, but before she could fight her way there, his heavy hand on her shoulder arrested her progress. The next thing she knew, he was slobbering a bunch of slurred words at her.

“I am sorry, I don’t want to dance this one,” she said and tried to continue on her way.

The man moved in front of her and gave a menacing look. “I am looking for my daughter,” he said with a breath of gin.

Pilar, who had never met her own father, went chill. Surely this goon could not be him. “Do you know me?” she asked with trepidation.

“No,” he growled, “but the bartender sent me to you.” He poked his thumb over his shoulder.

Mariano’s velvet voice sang out, “La Canción de Buenos Aires.”

“Who are you, señor?” Pilar’s voice shook. Her mother had told her her father’s name before she died.

“Miguel Garmendia,” he said.

Pilar’s heart did not know whether to lift or sink. This brute was not her father, but he was the father who had brutalized her friend Luz.

He pointed his thumb at the bar again. “He told me you know my Luz. I want to know where she is.”

“I don’t know, señor,” Pilar said.

He jutted his chin. “The bartender told me she has been in here with you. More than once.” His eyes burned into hers.

Pilar looked down at the black-and-white checkerboard tile beneath her feet. Behind Luz’s father, on the little stage, Mariano went on with his song. “I know her, but only slightly,” she lied. She made her voice sweet. “I will tell her you are trying to reach her the next time I see her, if that will help. Does she know where to find you?”

Garmendia grabbed Pilar’s elbow and squeezed it, sending a pulse of pain to her shoulder. “You tell her to come home, or else. Tell her I will kill her if she doesn’t, and I will kill anyone who keeps her away.” He let go of Pilar’s arm and lurched to the door. She did not take her eyes off him until he disappeared up the steps and out into the street.

She went to the bar and berated Lorenzo, the bartender, for pointing Garmendia toward her. “Don’t you ever let that animal in this club again,” she said, as if she had the right to command him.

She could not bring herself to dance any more that night. She stayed at the bar, with her elbows on the white marble and her hands holding up her head. She drank more than was her habit and listened to the longing in the songs written by displaced people like her mother, who had forever left behind her loved ones in Italy to look for a life without the threat of starvation. In the new world, she had found food for her body, but also awful loneliness. In the end she had died young and left only a barely grown-up daughter behind.

Now, amid the cheering mob at the rally, Pilar’s skin prickled with fear. Garmendia was here. If he found Luz, both girls would be in danger. Pilar could only hope the density of the crowd would protect them.

Suddenly the animated press of people around the girls went wild as Juan Perón, behind the microphones, raised his hands over his head and smiled warmly, nodding his approval at the adulation of the thousands surrounding him.

With a great flourish, he removed his jacket and slowly rolled up his sleeves. The crowd stamped, clapped rhythmically, and chanted the name of their jacketless hero. “Perón. Perón.”

* * *

Many of the men near Ramón Ybarra took off their jackets, too, and twirled them over their heads, shouting, “Viva Perón!” Anxious that he not be spotted as an interloper, Ybarra pasted on an approving smile and attempted to subdue his outrage. Wherever men went in Buenos Aires, they were required to show respect by wearing jackets and ties. No restaurant or movie house in this elegant city would admit a man dressed in the disgraceful way Perón chose to appear before this crowd of lowlifes. Ybarra swallowed the spittle he would have preferred to spray on the cheering monkeys around him.

On the platform, the idol of the scum loosened his tie and held his hands aloft. The noise of the crowd swelled again and then finally subsided to near silence as he began to speak. The voice that came over the loudspeakers was deep and warm and entirely confident, the smile he beamed at them sunny and sincere. There was nothing about the man that would indicate that he had just been stripped of power. Surrounded by flying flags and the adulation of thousands, he spoke of liberty and the glory of their nation, of the power of the workers. His amplified voice echoed off the surrounding buildings, whose stately facades and refined appointments lent an air of importance to his fine words.

Ybarra winced when Perón’s final gift to his sycophants elicited the wildest applause of the afternoon. Perón announced, in that irresistible voice, increases in wages for workers and an index tied to the cost of living, so that, according to Perón, the laborers who were ultimately responsible for the prosperity of the nation would not lose the gains they had made in the last three years. The bastard was reminding this mob, and anyone listening on the radio, of exactly what they owed to him, and only to him. “Perón. Perón.”

* * *

General Fárrell, the president of Argentina, listened to the radio broadcast in the Casa Rosada three blocks away, as did General Avalos, commander of the garrison, in his office north of the city at Campo de Mayo, and the heads of oligarchic families in their marble halls of power and luxury. All realized that Perón had scored an enormously powerful parting shot. What he had just said had been heard by millions all across Argentina and could not be rescinded without unleashing mass revolt.

* * *

On the edge of the crowd, near the car, Evita Duarte placed her hands over her heart when she heard her colonel’s words. He had not told her beforehand what he was going to say. Her whole being burned with pride and admiration. This man on the stage, her man, was the savior of the poor. And he was rubbing the noses of the bourgeoisie in their own shit and frustrating their attempts to destroy him. He was the most important, most valuable man in the country, perhaps in all of South America, and instead of being feted for the great leader he was, he was being tortured by a nest of snakes who had not an ounce of vision or leadership. Behind her admiration prickled a fear: this bold act of Perón’s could be political suicide. She wanted to save him. She had more balls than any of his enemies. Someday she would make them feel her wrath. Whatever their treachery and lies did to him, she would never leave his side.

Perón made a brave show of enjoying the festivities, flashing his sunshine smile, but Evita saw anxiety in his body, like a caged animal’s. He was an athlete, and when a fight was upon him, it showed in his gait: he moved swiftly with focus and intention, like the fencing champion he was, intending the épée for his opponent’s heart. Now he clasped the hands of his supporters, but as a conciliatory man. There was no edge of threat in his demeanor. She knew he trusted the army’s officers to follow their code of gentlemanly conduct and leave him to make a new future for himself. But she trusted none of them. Powerful people made up their rules as they went along, whatever worked for them, the way her brother used to declare different rules for boys and girls when he played games with her and her sisters. People who had the nerve to make up their own rules were the ones who won.

Evita punched her fist into her left hand. Perón’s enemies should all be erased from history. Evita swore in her heart that they would be, if it took her last breath.

* * *

Tulio Puglisi, from his position at the back of his union’s contingent, could not see the man behind the microphone, but he heard the impassioned speech and read between its vague lines an appeal to the workers to rise up for Perón, as if the whole idea of a union was for the workers to put their faith in one powerful manipulator, instead of in the collective. This rally was a miniature of the outpourings for Hitler and Mussolini that he had seen in the newsreels. If Perón’s supporters swelled in numbers, Argentina would see adoring crowds exactly like those in Rome who had chanted, “Duce. Duce.” But here they would clamor for “Perón. Perón.”

Nauseated by the thought, Tulio turned away from the man with the winning smile, and he saw her again a little distance away, Eva Duarte amid the crowd, wearing a green dress and grinning with pride. It would have been more like her to stick close to her colonel, but perhaps she meant to place herself in the middle of the throng so that she could take its pulse. Evidently she expected to position herself as an ordinary person so that she might learn the best way to influence the workers.

But Eva Duarte was not a woman of the people. She may have started out working-class or less, but now she wore clothes from Florida Street and rode around in a chauffeur-driven Packard.

While Perón left the platform and plowed through the crowd toward his car, Puglisi tried to follow the actress to see what she would do next. The army may have taken Perón down a notch, but anyone with half a brain knew he was still a threat. If Argentina was to be saved from a takeover by that fascist, Evita would have to be taken out of the picture.

* * *

“Oh my God,” Luz shouted into Pilar’s ear, barely audible over the applause of the people around them. “We have to get out of here.”

“Did you see him?” Pilar shouted in return.

Luz nodded her head and pulled on Pilar’s arm. They could hardly move. Pilar pushed and elbowed until they got free of the crush of people. She looked over her shoulder. “I think we have gotten away from him.”

“No. No. I still see him.” Luz’s voice was filled with terror.

Pilar could not see Luz’s father anywhere near them, but she sped away with Luz, across to Bolívar, through a knot of celebrating unionists, and around the corner. They crossed the avenida to where Perú became Calle Florida, both of them instinctively making for the safest place either of them knew, the shop where they worked.

Pilar paused in the doorway of a lingerie store and peered behind them. The streets here were nearly empty, though on a Wednesday afternoon in spring, at the hour of the promenade, the outdoor cafés should have been noisy with the chatter of porteños comparing plans for next weekend. Instead, the chairs were stacked and the striped umbrellas folded. Three blocks behind the fleeing young women, the crowd at the rally was beginning to break up.

“I think we are safe,” Pilar said.

Luz still looked frightened.

Pilar pulled her toward the tearoom across from Harrods department store, a block before Chez Claudia.

“I can’t afford to eat here,” Luz said.

“We’ll just have a cup of English tea. I’ll pay.” Pilar could not stand the tension. At least if they were in a place with other people, Garmendia would not have the nerve to attack them as he had promised he would when he accosted her in the tango club.

Pilar chose a table near the window so they could watch the street. The waitress eyed Luz as if she recognized her when they ordered their tea. Luz gave her an approving smile as if she were the real Evita. “One day I will buy you a hot chocolate and some cinnamon doughnuts,” she whispered to Pilar as soon as the waitress walked away.

In the street outside, the overcast day had turned black: one of those sudden spring tempests was about to descend. Luz soon became distracted by her reflection in the darkened window. As she finished her tea and Pilar counted out the change to pay, Luz said, “Are you going to the club to dance tonight? I want to come with you.”

Pilar was incredulous. “Are you crazy? If he saw you with me at the rally, that is the first place he will look for you. I told you he came there trying to find you. I told you what he said.”

Luz finally looked away from her reflection. “Who are you talking about?”

“Your father. You said you saw him in the crowd. He could be following us.”

“I didn’t see my father. I saw Lázaro.” She looked disbelieving. “It wasn’t my father. It was Lázaro. Torres.” Her voice was insistent, as if Pilar didn’t know the difference between Luz’s father and her ex-boyfriend.

“I thought you said Lázaro was twenty-eight and handsome.”

“He is. You said you saw him.”

“I didn’t,” Pilar said. “I saw your father. Not just now. I saw him before, when we got off the Subte, as we came up the steps. He was ahead of us.”

“I don’t think it was my father. He wouldn’t go to a rally like that. He doesn’t care about politics. But I saw Lázaro. I know I did.”

“Did he see you?”

“I’m not sure, but that’s why I ran away.”

“Oh my god. This is really dangerous.” Pilar could not imagine how bad it would be if both men found them.

Luz looked back at her dark image in the window. “Maybe not. I don’t think Lázaro would recognize me. He would think I was her.” She said the last word as if it were a prayer.

Pilar swallowed hard. “Let’s go to the shop before someone finds us.” She watched the street as they walked the last block, and she kept them on the narrow sidewalk, near the buildings, until they got to the front door. The shutters were closed. She used her key to unlock them, put them up, and opened the inner door with the same key.

Once they were inside, the rain came down in torrents. Pilar relocked the door. They went through the heavy green-velvet drapery to the back and sat in the chairs they used during work hours, Pilar behind her sewing machine, Luz next to her ironing board. Pilar stole out to the dark front door from time to time to see if there was anyone outside. Once the rain stopped, a few people went by, some of them carrying placards she had seen at the rally. She wanted to get to the club. Tonight was a special performance and a dance competition. She had promised Mariano that she would dance with him.

Luz primped at the mirror and whined that Pilar would not take her to club. “Look how nice my hair looks like this. I want to go.” The style was very like what Evita herself had worn that day, upswept in front, hanging down in waves in the back.

Pilar stood her ground. “It is just too dangerous. You have to go home and stay there.” Luz made a face but did not argue.

When Pilar went to the front door to leave, she saw a man standing in the doorway of the shoe shop across the street. He glanced at her through the glass of the door and quickly looked away. He could have stopped there just to get out of the rain, but the downpour had let up twenty minutes ago. She went back to Luz, who was rummaging around in the scrap bin, pulling out white tulle.

“Listen,” Pilar said, “I don’t think you should go out the front when you leave. There’s a guy out there.”

Luz looked startled. “My father? Lázaro?”

Pilar shook her head. “It wasn’t your father, and I don’t think it was Lázaro, either. I didn’t see this man that well, but he was not like you described Torres.”

Luz was twisting the tulle into a ball around her fingers.

Pilar tapped her on the forearm. “Listen! Whoever he is could be watching the store for your father or Lázaro. I am going out through the alley. You’d better, too. Go now and lower the shutter and lock up the front.” She gave Luz her key.

Luz said, “Okay,” but she continued to sort through the pieces of fabric.

“Promise,” Pilar insisted.

“Yes. Yes. I promise. I promise. Stop nagging me.”

“Okay. See you tomorrow.”

Pilar went to the back door, which opened onto an alley that ran behind the shops. The walkway was narrow and empty except for mops and buckets and trash barrels that the shop owners stowed outside their back doors. Pilar made her way to the end of the block and out onto the avenida toward the Subte and the club.

* * *

When Juan Perón left the rally with his closest allies in the unions, he went, wearing his tie and jacket, to an early supper at the Plaza Hotel. He was aware that not all the labor representatives supported him, but those eating steaks and potatoes with him in the sumptuously appointed private room knew which side their bread was buttered on. Every one of his companions urged him to do anything he could to restore himself to power.

Evita had gone straight home in the Packard. Alone with only the housekeeper, she listened to radio reports of packs of student protestors along the avenues shouting threats against Perón. “Epithets are also being hurled against the actress Eva Duarte,” the announcer reported. His voice was almost gleeful.

* * *

After Pilar left the shop, Luz stayed in the workroom, playing with fabric from the scrap bin, trying to fashion a hat like the dramatic white one with beautiful cabbage roses that she had seen on Evita the day the actress gave her this beautiful green dress. Pilar and Señora Claudia had said Evita’s white hat was ridiculous, like something from a lamp store. But to Luz, Evita looked like an English princess in it. Luz wanted to make such a hat for herself so that she could look like a princess, too. If Pilar had stayed she might have been able to show Luz how to do it. She always bragged about being a seamstress, even said that Evita’s mother had been a seamstress, too. But Pilar was taller and her body rounder. No one would ever mistake Pilar for the loveliest woman in Buenos Aires.

Luz pulled the stitches out of her failed attempt at a hat and touched up her hair and makeup. She took the key. Pilar had made her swear she would lock up the store and leave by the alley. Pilar always treated her as if she were an idiot.

She looked out into the alley. It was dark and creepy out there. Across from their back door was a boarded-up window covered with cobwebs. The air smelled of rotted leaves and mold. She was more afraid of that ugly place than of the elegant street out front. She knew how to be careful. She locked the alley exit.

She returned the scraps to the bin, checked to make sure the light in the bathroom was out. She even closed the workroom door before she went out through the dark showroom. She looked out through the glass in the front door. The doorway of the shoe store across the street was empty. The Boston, the coffee bar next to it, was closed, but its name in green neon glowed over its entrance. There was no one out there. Whoever Pilar had seen was gone.

Luz went out and carefully locked the front door. She was about to lower the shutter when someone came up behind her. She did not have time to turn or to scream before he put his hand over her mouth. She froze with fear.

A knife went into the middle of her back. She had lost all sensation before the assailant made five more cuts and left her bleeding in the doorway of the shop.

* * *

At that very moment, Detective Roberto Leary of the Federal Police was in the Palermo district, waiting in the parlor of an aristocratic Italianate villa to speak with a witness to a murder. The room Leary stood in, holding his fedora in his hands, was furnished with French antiques—lots of small chairs with delicate curved legs and seats of needlepoint, but not like the bright cushions his mother and older sister made. These had tiny stitches and subtle colors that matched the flower-patterned carpet beneath his shoes. The walls were hung with paintings of landscapes in heavy, gold-leafed frames.

Leary knew he did not belong in a place like this, but he did not belong in his job, either. He used to. Not anymore. With the help of his father’s brother, he had enthusiastically joined the Capital Police seven years ago, right after he left secondary school. In those days he was glad to have had a job at all, and one he thought he wanted at that. His first years on the force were pretty much what he had hoped: a completely masculine endeavor, unlike being in the house where he had grown up, after his father’s death, with all women—his mother, his grandmother, and his three sisters. During his first several years on the force, he had patrolled the barrios of his beautiful city. He picked up insolent compadritos with their fancy shoes and switchblades and rid Buenos Aires of thugs and jerks who plagued the neighborhoods. He had liked that a lot. Once he was promoted to detective, he grew to love his job.

But that was before the Capitals were merged into the federal force at the beginning of this year. Since the Federals had taken over, Leary’s motivation had waned, until now it was practically nonexistent. The job he used to do, the job he still wanted, was gone. Instead, his work had become more about politics than crime. This murder was a perfect example of the kind of sham investigation he spent his time on looking into the death of a student in an antigovernment demonstration. Ordinarily, such an event would have gotten less than lip service; except in this case, his captain owed the dead kid’s grandfather a big favor. The old guy was a bigwig demanding an investigation. As far as Leary’s chief was concerned, Leary was an underdog, first of all because he had come from the Capitals, which the higher-ups, all ex-Federals, considered a bunch of pussies. And he had another strike against him. His uncle, who had pulled strings to get him the job in the first place, had died. Now Leary had no godfather with clout to defend his interests. So he had to do the dirty work and smile, and today that meant pretending to find out who had killed the kid. He would have liked to go after the murderer for real, but the student had died while demonstrating against Perón, and Police Chief Velasco was beholden to Juan Perón for his position. Figuring out how far his boss expected him to go with this investigation was harder than solving any crime. Guessing was an ex-Capital cop’s only alternative. Right now Velasco’s own position was tenuous. The big boss’s own ass might end up in a sling. The scuttlebutt was that Perón himself was about to be arrested—to get him permanently out of the way. Would Velasco throw his own patron in the pokey? There was always a chance Velasco would get tossed out of office on the heels of the departing colonel. That was a lot to hope for. Most of the men on the force supported Perón because he was a supporter of the hardworking poor. Leary liked that, too, so he guessed he liked Perón. Sort of. But that bastard Velasco was a different question entirely. Leary couldn’t find anything to like about him.

Leary was determined to keep his job, so for now his best bet was to make a show of solving this case, but not to try too hard.

The dead student, Alberto Ara, had lived in this palace. His ilk had long-since abandoned their educational opportunities for the chance to shout anti-Perón sentiments in the streets. The kids were demanding a return to the nation’s constitution. If Leary thought about it, that was what he wanted, too. That kind of move would force the cops to stop being political and solve real crimes. Which was what Leary wanted to do, instead of working for a political hack who didn’t give a rat’s ass who had killed the boy.

He glanced at his Bulova watch—like his job and his car, a gift from his dead uncle. It was going on eight o’clock, and he hadn’t eaten since noon. He was trying to figure out how much longer to wait when a door in the room’s walnut paneling opened and a guy of about twenty-three walked in. Leary caught a glimpse of a weeping woman in the hall before the door closed on her hurt, inquiring glance.

“Who are you and what do you want?” the youth demanded without preamble. He was a slender, good-looking boy, a couple of inches taller than Leary. His dark, perfectly tailored suit cost five times as much as any young detective’s.

Leary shifted his fedora to his left hand and extended his right. The youth did not take it. Leary shrugged and said only, “Inspector Roberto Leary.” He could no longer say “of the Capital Police,” and he wouldn’t say, “of the Federals,” because they were known throughout the land as a bunch of heartless thugs.

“I am Eduardo Ara,” the young man said. “The maid said you were here about my brother’s murder.” He looked something between grieved and peeved.

“Yes,” Leary said. “I am supposed to be investigating who killed your brother. I am sorry to have pulled you away from your family at this moment.”

“But you have, haven’t you?” His sneer made Leary want to paste him one. This rich boy was obviously not accustomed to being polite to someone as lowly as a policeman.

“I just want to ask you a few questions, to see if I can get a lead as to who might have…” Leary left the rest of his thought unstated. He pointed to a stiff settee that looked as if it would be only slightly less uncomfortable than continuing to stand, but before he could ask to sit down, the kid shook his head.

“I am getting ready to take my mother and my grandmother to the country now that that travesty of a funeral is over. It was a circus, you know. Cops on horseback, treating me and the other students like we were criminals.”

“I’m sorry,” Leary said, trying to get the kid to soften up and give him information. “I’ll try to be brief as possible. What can you tell me about the circumstances of your brother’s death?”

“Alberto and I are … were students together,” Eduardo Ara said. “He was two years younger than me. We were in a group of other students demonstrating for a return to constitutional government. We were entirely within our rights. We have to stand up for what we believe.”

Leary smiled without really agreeing. This elegantly dressed, pomaded scion of the upper classes was not exactly the type one would find rabble-rousing in the streets in an ordinary city. But Buenos Aires was not ordinary, and neither were the porteños, her citizens. Everyone and everything in this cosmopolitan capital gave the impression of being misplaced, as if a piece of Spain or Italy had been torn off from the little continent north across the water and stuck here on the edge of a vast wild land of Indians and desolation. Argentine kids, like this one, seemed to have no idea how many young men their age had been slaughtered fighting a war all over the world in the past few years, while here they safely ate steaks, pretended to study architecture or literature, and tried to seduce one another’s sisters.

Ara’s sneer deepened into disdain. “Those repressive goons who attacked our group were probably members of your police department. How am I supposed to believe that you will honestly try to find my brother’s murderer?”

Leary hated it that the young snob was probably right. He chose to ignore the remark altogether. “Before you leave town, what can you tell me that would help my investigation? I want to try to catch the people who murdered Alberto. At the very least, it will comfort your grandfather to know his grandson’s death did not go ignored.”

The kid began to inch his way to the door. At that rate, it would take him several minutes to get there. This baronial parlor was three times the size of Leary’s whole apartment.

“My grandfather is dreaming,” Ara said. “There is no way anyone will ever be accused, much less punished, for what happened. Stop acting like anyone in the government gives a shit about one more dead student.”

Leary touched Ara’s shoulder, stopping him from continuing to the door. “The fastest way to get rid of me would be to tell me what you know.”

Ara looked unconvinced, but he answered. “There is nothing to say. We were marching to demand the rule of law. A car went past, its horn screeching. A guy in it stuck the nose of a machine gun out the window and fired into the crowd. Alberto took a volley.” He looked as if he would burst into tears.

Leary waited for him to regain control. He took his notebook from his jacket pocket. “Can you give me any detail that might identify the car?”

The boy shook his head. “I was busy diving out of its way. It was dark green.” His face turned defiant. “A military color, I believe.” He strode to the door and opened it.

Leary saw that the kid felt guilty that he had saved himself and not his brother. He put his fedora back on his head. “I am sorry for your loss,” he said. “Take care of your family.” He didn’t wait for Eduardo to see him out but marched past him to the villa’s front door and got out of there as fast as he could.

He drove back to police headquarters, writing his useless report in his head on his way. He was barely through the front door when his captain intercepted him and handed him a slip of paper with an address on Florida Street. “A woman—stabbed to death in front of a modista’s shop. A patrol car is already there,” was all he said.

Leary looked at the address and then up at his boss’s retreating back. He was not going to get any help from that self-centered son of a bitch. Nor anything to eat for the next couple of hours. He shoved the paper into his pocket, made an about-face, and went back to the parking lot. This was a strange call. Violence was prevalent these days, but most of it was political—like the death of the Ara boy. Streetwalkers might catch hell; they always did, but they would not be hanging around at a place like that. Florida was a street where pickpockets roamed, especially at crowded times like Easter and Christmas, but the switchblade wielders who plagued the rest of the city rarely, if ever, intruded there. Leary had never heard of a woman killed with a knife on the most exclusive shopping street in town.

He drove his dead uncle’s classy red Pontiac to the scene of the crime. With the traffic sparse and the center deserted, it took him less than twenty minutes. He passed the opulent Galerías Pacifico—a four-story crystal palace of expensive stores and marble coffee bars. Flood lamps here and there on balconies lit up sections of the brown stone facade, but the manikins in the windows stood in the dark, so no one could see how grand they looked in their silk suits and slinky cruise wear. The usual shoppers, diners, moviegoers from among the idle rich who might have jammed the pedestrian area roundabout were absent thanks to the early-evening storms and the turbulent times.

Leary’s tires rumbled over the cobblestones as he turned from Córdoba onto Florida. He wondered what it would be like to have nothing to do but play polo and look for the latest fashions. The car he drove was the only stylish thing he was ever likely to own, inherited from his father’s brother who had made good in the U.S.A. and had come home just in time to die. The Pontiac was beautiful and purred to Leary as it glided down the narrow calle.

Cast-iron streetlamps spilled pools of light at intervals along the empty walkway in front of shuttered shop windows. The rain had left puddles that glistened in his headlights. The patrol car he was looking for was stopped on the narrow sidewalk halfway between Corrientes and Sarmiento. Its high beams shone into the doorway of a dress shop. Leary scrunched his whitewall tires against the curb as he pulled up behind the other car.

As soon as he got out, he saw the victim. Oh, shit. The body lying in the entryway was a girl’s, small and slender. Very young. Bad enough to be on permanent night shift when it meant investigating carved-up compadritos killed in their petty gangster knife fights. But a dead teenage girl? Younger than his youngest sister? Shit. Shit.

“Hola, muchachos,” he called without enthusiasm to the uniformed men standing over the body. They parted, revealing the girl’s head. Disbelief stopped him in his tracks. It could not be. The dead person was the actress Eva Duarte? The mistress of the just deposed vice president of Argentina? And the captain had sent him to investigate? Velasco had not come himself? A murder like this should have brought out the minister of justice, if there was one after the government housecleaning of the past twenty-four hours. Maybe Velasco himself had already been thrown out—creature of Perón that he was.

“I don’t think it’s her,” Ireno Estrada said. He was short and muscular and never kept his shirt collar buttoned once he left the station. Of all the nephews of minor-league politicians on the force, he at least had a brain in his head.

Leary pushed back his fedora and leaned over the body. “She could have fooled me.” On closer inspection, the nose, the mouth did not look exactly like the face on the covers of his mother’s soap opera fan magazines, but everything else … “Was she on her back like this when you found her?”

“No. I turned her over to make sure she was dead.” This was from Estrada’s chubby partner—Rodolfo Franco, whose mother’s second husband had the contract to pick up garbage in the Palermo district. The well-to-do refuse collector had dumped this particular piece of low-wattage trash on the Buenos Aires Municipal Police Force. Anyone with two centavos’ worth of brain cells would have concluded, from the size of the pool of blood surrounding the body, that there was not enough left in the poor girl to keep a mosquito alive.

Her dress, where it was not soaked with blood, was pale green and looked expensive. A small, cheap purse on a metal-chain handle hung from her forearm. The real Evita Duarte, he was sure, would not have been caught dead in these tacky stiletto-heeled patent-leather shoes, one of which was half off the dead girl’s foot. But this waif had been caught dead in them. Where would a girl who could not afford decent shoes have gotten this dress?

He reached up and closed her eyes, then opened her purse. It seemed almost as much of an invasion as the knife had made. He took out a small glassine envelope with her identity card and held it up to the beam of the patrol car’s headlights. “Luz Garmendia. It says she lives on Colombres. She was sixteen.” His voice choked on the last word.

There was one peso, sixty-nine centavos in the purse, and a handkerchief edged with the kind of lace working-class girls made with fine cotton. Then, he noticed a glint of metal at the margin of the pool of blood, near the girl’s right hand. “A key.” This was odd. Poor girls did not live in houses that were ever locked. “The dress is too expensive for the shoes and purse.” He was thinking out loud.

Franco guffawed. His soft belly wobbled when he laughed. “Big expert in girls’ dresses, are you, Robo?”

Leary would gladly have strangled the knucklehead. “I have three sisters,” he said instead of a curse. He had been warned too often that his arrogance toward the politically well connected was not a proper path to promotion on the force. “I don’t imagine you know anything at all about women.”

An ambulance siren approached from the north. Leary got to his feet and on a whim tried the key in the lock of the shop door. It opened. He looked up at the sign across the top of the entrance. CHEZ CLAUDIA, it said in large gold letters, and under it in elegant script, STYLE POUR LES FEMMES.

“Reno, find out where the owner of this shop lives and get me a phone number for him.” The ambulance pulled up. The spinning red light reflected off the girl’s blood.

The driver approached with a stretcher. One glance and he looked stunned. “Holy God!”

“It’s not her,” Leary said. But a suspicion was beginning to form in his mind that whoever had stabbed this poor girl had made the same mistake.

* * *

All over Buenos Aires at that moment people were worried, angry, puzzled. In their hovels in the villas miserias around the factories on the periphery, the poor rejoiced over the parting gifts Perón had announced over the radio in his farewell speech, but even more, they feared that his fall from power would take away the gains they had won from his hands.

In posh apartments overlooking lush parks, or on patios with views of star-filled skies, and in the mahogany-paneled bar at the Officer’s Club in the Palacio Paz, the rich and the powerful told one another of their outrage over Perón’s audacity. They despised his final attempt to buy off the trash who did the dirtiest jobs in the land. More than a few of them believed Perón’s mistress was behind his outrageous behavior. They condemned “that woman” as the greatest threat to their society. Much as they hated Perón, it was the avaricious actress they cursed. It terrified them to think Evita, the venal and social-climbing virago, would resurrect her lover and rob them of their lifestyles of luxury. The words of the tango told them: the guilty are always the women. More than one self-satisfied plutocrat let out a dirty guffaw when he pointed out that like the woman who had committed mankind’s original sin, this viperous temptress was called Eva.

It was well after midnight before the millionaire denizens of the Jockey Club or the Círculo des Armas turned their minds toward practical ways in which they might avoid a calamitous uprising incited by Señorita Duarte.

Meanwhile, the actress was, from the start, all practicality. Before darkness fell, she sent Jorge and Cristina to the Brazilian grocery on the next block to buy canned foods that could sustain them if they were forced to endure a siege. She filled the bathtubs with water, in case the officials decided to cut them off from the necessities of life. She packed suitcases for a quick getaway and considered sewing her jewels into the hems of her skirts.

Perón took a soldier’s precautions, closing and locking the shutters, checking and loading his pistol, and posting three sergeants armed with machine guns at his apartment door.

Chapter 2

Thursday, October 11

In the wee hours of the next morning, Rudi Freude, the son of a German immigrant billionaire and, some say, Nazi spy, who had been hard at work arranging for the importation of German gold and brainpower, drove a Benz touring car to the servants’ entrance of the massive, elegant apartment building where Perón and Evita had enjoyed their illegitimate cohabitation. Unnoticed by the crowd watching the front door, the little lady and her lover and a couple of small suitcases were swept away to Tres Bocas, a remote retreat where the bluebloods from the Avenida Alvear kept enormous country “cottages,” and where Evita and Juan could secret themselves in the home of a supporter. Domingo Mercante, Perón’s most trusted adviser, accompanied them.

The Benz arrived at a dock where the boats of the wealthy awaited summer, when they would take their owners along tree-lined channels to their peaceful getaways. Once the fugitives had boarded one of them, Freude wrapped Evita in a blanket for the chilly ride.

Subdued and worried, Perón sat in the stern of the boat and whispered with Mercante. Evita pulled the blanket around her like a shawl and stood at the railing. In the moonlight, the water was the color of pewter and looked solid enough to walk on.

Freude tried his best to cheer her, plying her with hot coffee from a thermos and pointing out huge villas where, in the gardens, white blossoms of spring fluoresced in the midnight moonbeams. “I was at a party in that one,” he said of a two-story mansion, still boarded up and awaiting the vacation season. “It belongs to a friend of my father’s named Wagener. They have a great art collection, including a beautiful portrait by an artist named Klimt. I wish I could show it to you.”

Evita wondered how he could think about pictures under the circumstances. She glanced back at Perón, hunched over, his hand cupped, lighting one cigarette from another. “I wish we were on a boat to Paris,” she said.

Rudi gave her a doubtful smile. “Beautiful place,” he said. “I was there often after we took it in forty-three. I am sure you will see it one day.”

She fell silent. A dull, cloudy Thursday was dawning by the time they finally arrived at the safe house. It looked more like a Black Forest chalet than an Argentine hideaway.

Once Perón and Evita were delivered, Freude and the loyal Mercante took their leave.

Perón put his arm around Evita as they waved good-bye until the boat disappeared into the gray gloom that smelled of mud. Perón spoke German to the caretaker, who built them a fire in the fireplace, brewed them some coffee, and trundled off to his apartment over the stable.

They sat close together on a soft sofa before the fire. “Is Mercante going to get the union leaders to stand up for you?” she asked him.

“He says he will do everything humanly possible to reverse the events of the past few days, but it’s a tricky business,” Perón responded.

“You will need all your strength to fight those lily-livered idiots. If you show them any weakness they will eat you alive.” She delivered the line as if it were from one of her scripts when she had played Catherine the Great and Queen Elizabeth on the radio. For a moment she had an eerie feeling that her real life was being created by a scriptwriter for a radio drama. She squeezed his hand. She wondered if she would ever be an actress on the radio again. That bastard Yankelevich had called her and summarily fired her from Radio Belgrano the second Perón resigned. But she did not speak of this. Perón was too discouraged already. She snuggled closer to him.

His sigh seemed forced, like that of an actor trying to make it heard over the airwaves. “I have warned Domingo to cooperate with the Federal Police if they come looking for us.”

“If?” she asked, in a voice uncharacteristically satiric, completely atypical of her way with her colonel. “Is there any doubt that the officers and the ruling class will do whatever they can to stop you from helping the poor? And without Velasco in charge, they now have the police in their pockets.”

At almost that very second, a member of the police force that Evita so feared telephoned Perón’s apartment on the Calle Posadas and spoke to Jorge Webber, the chauffeur, who had been left to hold down the fort. Roberto Leary was glad to hear that the actress had gone out of town in the middle of the night to a secret hideout over a hundred kilometers from the city. If there was a madman out to kill her, at least she was safely in hiding. Leary gave Perón’s man his phone number and extracted a promise that Webber would call him if the actress returned to Buenos Aires.

Leary inhaled deeply to steel his nerves. This first task had turned out to be easy. His next job would, he was sure, be extremely unpleasant. He dialed the phone number of Claudia Robles, the modista who owned the shop where Luz Garmendia had been stabbed to death.

* * *

At ten that morning, Hernán Mantell drove Claudia Robles to meet a policeman at her shop. Hernán was at war with himself. With the latest upheaval, the government could totter either way. The journalist in him hoped for a return to the democratic constitution, which had been largely ignored for decades and then totally suspended when the military took over the government two years earlier.

At that point, citizens’ rights went out the window. The newspapers had been censored, but now Perón’s departure left only the indecisive Fárrell in charge and the army with only a tenuous hold on power. If the future tipped in the direction Hernán hoped for, freedom of the press might be restored.

Hernán’s editor had called him at seven thirty to tell him that General Avalos was taking over as minister of war, which could mean only that Perón’s ouster was complete. Still, the army had almost no support among the people—less actually without Perón, since he at least had his descamisados down in the factories on the periphery. At this point, matters could open up or descend into even greater repression. And what of Perón? He didn’t seem the type to go quietly into that good night.

Hernán’s work, even his existence, hung in the balance, but whatever his anxieties for his own future, the horrible news that had come just before dawn—of the murder of the girl Luz—had torn his mind away from those worries. How could he leave Claudia, his wife in all but name?

He had had a lawful wife when he was barely out of his teens, a willing girl who had seemed almost as desperate for sex as he had been. When they were discovered together in the backseat of her father’s car parked in the family garage, he had been forced to marry her. Nothing much had happened between them after that. She repented her wanton ways, and as quick as she had been to open her legs before marriage, she kept them firmly closed after the hastily arranged ceremony. They grew apart, had not seen each other for decades, but he could not marry Claudia—the love of his life—because there was no divorce in Catholic Argentina.

Duty called him to work, but love kept him with Claudia, at least until he delivered her into the arms of her father. The old man had taken the Subte to arrive at the shop on Florida at nine. By the time Hernán drove Claudia there, Gregorio Robles probably would have broken the news to Pilar, the seamstress. Having lovingly raised his daughter by himself, Gregorio would know how to comfort the young Pilar. He would also be there to greet the detective who was coming to interview Claudia about the murder. That is, if the policeman arrived early. Devotion to duty was not a signature habit of the Buenos Aires police force.

One of Hernán’s biggest worries was what Claudia and her father would say to the investigator. Some people were taking the recent relaxation of the state of siege as a signal that the citizenry was safe from repression. But Hernán knew that if Claudia or old Gregorio said anything too controversial, they would wind up on somebody’s list of subversives.

When Claudia got into the car, she saw the worry in Hernán’s glance and mistook it for annoyance. He was getting fed up with her uncontrolled outpouring of grief. She did not want to irritate him further, but she wound up spending the entire ride from their apartment to her shop recounting her relationship with the dead child: a story Hernán knew, but that she could not stop herself from repeating. “I thought I was helping her,” she said for the tenth time that morning. She stared out the window and relived the shock and disbelief of receiving the horrendous news that had come before the break of light.

A telephone call at that hour never brings good tidings. When they jumped out of bed and ran for the phone in the parlor, they both had imagined the call would be for him. Some political crisis required coverage—there had certainly been enough of that lately. She let him pick it up. When he said, “It’s for you,” and handed her the phone, she could not imagine who it was. Her father lived in a small apartment on the floor just below them. It could not be him. He did not have a phone. The shop? A fire? But it was worse. So terribly worse. Neither of them had slept for the rest of the night.

Sitting in the car, she rubbed her eyes with her soaked linen handkerchief and again went over the day, a little more than six months ago, when she had taken Luz Garmendia under her wing.

Almost daily, from the window of her third-floor apartment she had seen the tiny and timid girl of fifteen bringing lunch to that brute of a gardener, her lover Lázaro Torres. He repeatedly abused the child, spitting on the food she had prepared, calling it shit, and flinging it in her face. If he did such nasty things in public, Claudia did not even want to imagine what he did to her in private.

She had discussed Torres’s behavior with her father, who then wanted to talk to the gardener. She could not allow that. The frail old man was no match for the muscular Torres. Gregorio had told her what the neighbors were saying: that the girl Luz had run away from a brutal father. “This is the problem of parents being unkind to children,” her father had said. “The children get used to it and expect to be abused all their lives. They never learn to stand up for themselves.”

Out of fear, Claudia had kept her peace with the situation until she could no longer stand the thought of the girl’s suffering. One day, she decided she must intervene. She waited at home until noontime, watching out the window until Luz approached, delivering her lover’s lunch. Claudia quickly went down the stairs as if she were in hurry to get to work and secretly handed Luz a slip of paper as she passed the girl on the sidewalk in front of the building. She did not look back, but she heard the child presenting her bastard boyfriend with another disdained lunch. Later that day, Luz called the number on the paper. Claudia invited her to the shop, gave her a job, and found her a decent place to live. She had felt so happy with herself, so self-satisfied that she had rescued the girl. Now Luz was dead, and Claudia was certain that if she had let the girl be, she might still be alive. She also knew it was probably Lázaro Torres who had killed her.

As Hernán pulled his old Ford coupe up to the curb in front of the shop, he took her hand and kissed her damp palm before she got out of the car. “I’ll try not to be too late,” he said. “When my editor called this morning, he told me Perón has left town. If he just keeps going, it could be the end of him, but the situation is heating up in other ways. I promise I’ll do my best.”

She leaned across the seat and kissed him. The apology in his eyes told her clearly what his words belied, that the political events would keep him from her on the day she needed him most. But she knew that La Prensa, his newspaper, would be one of the first to be suppressed if events turned out the way his worst nightmares warned him they might. And the facts of Argentina’s past and present told them both that they probably would. She was as passionate about her work as he was about his, but his was serious. She made expensive dresses; he reported and recorded events that would become history. He loved her. She knew he did. But he was going to do his duty and leave her with her grief.