Read Part 1 of this thrilling 3-part series first over at Thought Matters!

The Miyazawa family’s house was a fair size, especially by Japanese standards. It stood in a municipal park in Setagaya, a largely residential ward clinging to the western limits of Tokyo. Soshigaya Park has quaint walking trails, sports pitches, a playground for children, and, on its fringes, a picturesque little canal with crooked old trees hanging over its banks. In 1990, there were 200 houses in this park. A decade later, following park expansion, there were four.

Today, there is only one.

In the summer, its lawns are not mown. In the fall, leaves are not swept away. At night, its lights do not come on. And if you walked past it today, you’d be likely to miss it. You’re looking for a side path blocked off with little cones. The house itself is boarded up now, fenced off, with three stories of tarpaulin shielding it from public view. A policeman stands guard outside, hands on his hips, because this is no longer a house. It is a shell, a mausoleum.

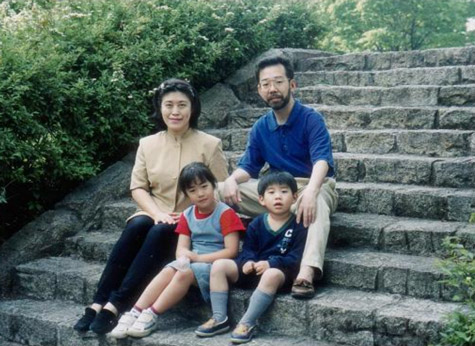

Take a second to look at the Miyazawa family again. Do they not look plain? So ordinary. What you might find in an encyclopedia if you looked up the term “nice people.”

In the photograph, time frozen as it is, we see the father, Mikio. He’s 44, slim, bearded, and bespectacled. He works for Interbrand—corporate identity development. At school, he loved theatre and puppetoon animation. He wears an ocean-blue polo shirt and moccasins, allowing two fingers to touch the shoulder of his son sitting below him. It’s the only trace of visible affection.

Yasuko, 41, although almost smiling, looks more rigid. She wears a beige blouse, her hair neatly plaited, hands in her lap. She’s a teacher, and she looks like one, somehow. A nice teacher, but one that stands for no malarkey.

Niina, 8, is cute, rosy-faced, and wearing Velcro trainers. She’s in the second grade, attending piano and ballet classes. She mimics her mother’s pose, in my mind, keen to please.

Her little brother, Rei, is 6 years old. His legs are apart, and he fiddles with his fingers, looking to the camera open-mouthed. Because of his pose, I imagine him as a touch more rebellious than his sister. He wears sailing shoes, just like dad.

Nobody is quite smiling. Nobody is giving away much.

So what happened?

On the night of December 30, 2000, a person broke into their house and murdered them all. That person then spent up to twelve hours in the house, eating their ice cream and browsing their internet before leaving in broad daylight.

A brutal home invasion such as this would be a rare thing in most places, let alone in Japan. To give you an idea, in 2015, reported crime in Japan fell to a post-war low. Homicides didn’t even break 1000[1]. This despite a population of almost 130 million. (For context, there were over 100 murders in Honduras in the first ten days of the same year.) I’m not saying that bad things don’t happen in Japan—of course they do. But when you compare their numbers, mutatis mutandis, to much of the rest of the world, murderous home invasions in Japan just don’t happen.

And yet.

Let’s start with bare facts. We know that Mikio died first. This seems like a logical place for a killer to start if one considers the father the main threat. He was stabbed to death, probably in the hallway. Next came Yasuko and Niina, who had attempted to hide. They, too, were stabbed to death. Finally, the killer came for little Rei, still in his bed. One can only hope he was asleep when it happened. But here the killer broke form. He smothered the boy to death.

This detail must have been significant for the police. There seemed to be no blood lust in this final act, no orgasm of violence. Perhaps the killer didn’t want to be looked at? Or perhaps he felt it was unnecessary to use the knife.

Either way, The Tokyo Metropolitan Police, the largest police force in the world, responded as you would expect. They ended up putting near a quarter of a million officers on the case—an astonishing figure. Imagine the entire population of Plano, all of them police officers, all of them working around the clock to find one man. A single man.

And it wasn’t as if the killer was shy about leaving behind evidence. The TMPD bagged over 12,000 pieces of it. First and foremost: the murder weapon, a long sashimi knife, which police discovered he bought that morning for around $40. It doesn’t take Perry Mason to work out this shows pre-meditation. The killer also left behind his blood, having fought with Mikio. Significant amounts of blood, too. The police found that after the murders, he tried to patch himself up. When he ran out of supplies, he moved on to using the mother’s sanitary pads, (which he left in the bathtub).

Blood analysis revealed an intriguingly rare profile. The killer was half East Asian—Japanese, Chinese or Korean—and half Mediterranean—Spanish, Portuguese, or Italian. The strange details didn’t stop there. He left behind his clothes, which the police described as “young,” including footprints for size 9 Slazenger sneakers, large for Japanese standards. On his clothes, there were traces of zelkova leaves and bird droppings. In his fanny-pack, there were sand grains from the Mojave Desert. On his handkerchief, there were traces of his aftershave—Drakkar Noir, winner of the 1985 FiFi Award for most successful men’s fragrance. (Incidentally, the handkerchief was ironed, which always struck me as weird. Is this a pernickety person? A clean freak? Or just tidy?)

At some point, the killer used the toilet without bothering to flush. His feces revealed him to be likely a vegetarian. At least, he had eaten sesame seeds and string beans the day before. He used the family computer twice, once at around 1 a.m., and again at 10 a.m. He ate four ice cream cups as he browsed the family PC, and, at some point, looked up theatre groups for that day in Tokyo. There was something so Goldilocks about it.

When the killer was done with the house, he took an old sweater and walked outside. Sixteen years on and still out there, he may as well have walked off the edge of the earth.

But nobody just vanishes. So where did he go? As you can imagine, those quarter million cops I mentioned looked at this case from every angle. They looked at the mother; they looked at the father. They wondered about money owed to the wrong people. Affairs. Some secret pathological hatred of the family. They even took away the family’s nenganjo (New Year greeting cards) for clues.

They did their victimology as you would expect, but they never found the killer. Nor did they, or anyone else for that matter, come up with even a viable theory. There have been several posited—robbery gone wrong, etc.—but none of them ever really stand up to the pure oddness of the act itself.

Today, from that quarter million cops, around 40 officers remain attached to the case full-time. They still bounce around theories. They still wait by the phone. They still hand out flyers at the train station. They visit the house every year on the anniversary of the murder to bow and pay their respects to the family. Young men, now veteran cops. There will have been retirements. Birthday parties. For that 40, I wonder if they feel stuck, frozen in the mystery of such an aberration. Do they think about the Miyazawas often? When they’re watching TV at home with their families, for example.

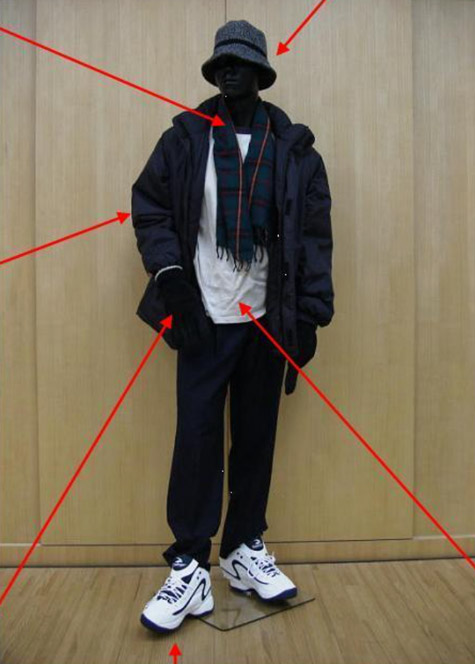

And what of the killer? He may even be dead. Nobody can know. My feeling? He simply moved on and reinvented himself. He’s probably far away. Maybe he has a family of his own. But inside, he’ll still be that man, capable of massacre. A very particular man. An individual. Someone. Someone who travels. Someone who most likely doesn’t eat meat. Someone who likes masculine-smelling French aftershave. Someone maybe cognizant of more than one culture, with more than one passport. Someone who looks like this:

Someone who, on the morning of the 30th of December, sixteen years ago, for whatever reason, bought a knife. Someone who stalked through the darkness of Soshigaya Park, his Slazengers crunching over the brittle, blanched grass, towards a home with the intention of carving an entire family out of existence.

Someone.

Read an excerpt from Blue Light Yokohama!

To learn more or order a copy of Blue Light Yokohama, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Nicolás Obregón is a British-Spanish dual national and grew up between London and Madrid. He has worked as a steward at sports stadiums, an editor in legal publishing and a travel writer, falling in love with Japan while on assignment for a magazine. Blue Light Yokohama is his first novel.