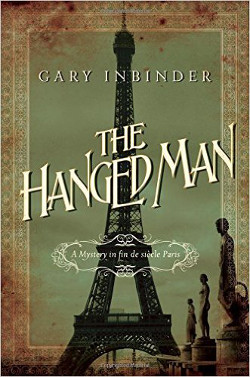

The Hanged Man by Gary Inbinder is the 2nd book in the Inspector Lefebvre historical mystery series.

The Hanged Man by Gary Inbinder is the 2nd book in the Inspector Lefebvre historical mystery series.

It is the summer of 1890 in Paris, and Inspector Achille Lefebvre is looking forward to escaping the sticky weather, when his holiday plans are sidetracked by the discovery of a man dangling from a bridge in a pretty little Parisian park.

The police photographer assigned to record the crime scene, Gilles, immediately assumes that the dead man is a suicide, but Lefebvre is not one to make such hasty observations. He approaches the corpse as if an artist—M. de Toulous-Lautrec is an acquaintance—and his eyes are open for clues. “There are always clues, Sergeant,” Lefebvre reminds his second-in-command, Sgt. Rodin. Rodin, who admires his boss and his use of the latest forensic techniques to solve crimes, is certain if there are clues to be found, Lefebvre will suss them out—and Lefebvre does not disappoint.

Someone had removed the collar and necktie to make way for the noose. He made a mental note to have the area searched to see if they could be found. The nondescript dark brown suit was neither cheap, nor expensive, and lacked any obvious patches, holes, or other signs of wear. The black leather boots had been polished recently; there was little wear on the heels and soles. The shoes would have been muddied if he’d gone off the footpath. Leaves and dirt might have clung to his clothing. There might be tears if a sleeve had caught in a branch.

There’s also a note pinned to the corpse’s jacket—a note everyone but Lefebvre assumes is a suicide note, although it is written in a foreign language and none can read it. Mildly disappointed that his team is so dazzled by the obvious, Lefebvre asks, “Is perception reality?”, and continues to gather evidence, questioning every assumption being made about the case before them, until there’s more data to process.

This is the second of Gary Inbinder’s mysteries set in fin de siècle Paris, and unlike many historical novels, the book has an even balance between the investigative elements and the historical elements. The history is there—Lefebvre is fond of musing about the gifts the hated Empire left the citizens of Paris—but the plotting is immaculate and the investigation is pieced together the old fashioned way, one clue at a time. And, in Lefebvre’s investigation, no clue is to be taken at face value.

“It’s a note pinned to a dead man’s jacket. As of now, neither you nor I know who wrote it, when, where or to what purpose.” He rose to his feet and made a gesture pointing to the end of the footbridge. “This bridge, M. Legros, is a means of getting from point A to point B and is supported by an arch. Think of it as analogous to our investigation. We are at point A, just beginning to cross the lake on our way to a destination, over there, the Temple of Sibyl.” Achille made another illustrative gesture.

“Now consider each clue, each relevant bit of evidence we discover as a stone in the arch. To reach our objective, we must first build the bridge. Omit one block and the whole thing will collapse and tumble twenty-two meters into the water below. Moreover, we are not winged creatures who may take flights of fancy over the lake, skipping the laborious task of building a sturdy bridge.”

Having made his point, Achille turned his attention back to the note. “The script is indeed foreign; it’s Cyrillic, used in writing Russian, Bulgarian, Serbian, and other Slavonic languages.”

Legros smiled broadly. “Yes, M. Lefebvre, and now you’ll see why the other item I discovered is of particular interest.” Legros rose and stood next to Achille. He took a pair of tweezers from his breast pocket, opened an evidence bag, retrieved a cigarette butt, and held it up for Achille’s inspection. “It’s a Sobranie, isn’t it?”

Achille recognized the distinctive paper and the cardboard tube filter. “Where did you get this?”

And so, the first clues are examined and the first two stones are put in the arch. By the time the “bridge” of the investigation is finished, the writer will have played fair with his readers, teasing them with the interlocking puzzle pieces and challenging them to solve it for themselves.

The Hanged Man is an excellent follow up to The Devin in Montmartre, a book that not only delivers the details fans of historical mysteries crave, but also serves up a solid procedural narrative that does not cheat the clues. There are always clues…if you know where to look.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Katherine Tomlinson is a former reporter who prefers making things up. She was editor of Astonishing Adventures Magazine and the publisher of Dark Valentine Magazine. She edited the charity anthology Nightfalls. Her dark fiction has appeared in Shotgun Honey, A Twist of Noir, Luna Station Quarterly, and Eaten Alive, as well as anthologies, including Weird Noir, Pulp Ink 2, Alt-Dead, Alt-Zombie, and the upcoming Grimm Futures, which she also edited. Her most recent collection of short stories is Suicide Blonde. She sees way too many movies.