What are you left with when you take away a superhero's origin story? A costume, some powers, and…that's about it.

Origins are huge part of the standard comic book character template—especially in movies—but they can also present problems. As I mentioned in my last piece about the Phantom Stranger, some superheroes bend under the weight of specifics. Others need their origin stories constantly updated or moved forward in time—like the Teen Titans, Iron Man, Nick Fury, and others whose popularity rests more on them being relatable characters and less on their iconic status.

Black Orchid was an interesting variation on the superhero origin story. For over a decade, she didn't have one, and that left her unencumbered by a secret identity, a defining personality, or even a known power set. Bystanders could figure out her capabilities by watching her in action, but she always had another ace up her sleeve—some power she hadn't previously revealed. She could fly, she was bulletproof, and was exceptionally strong; she was also apparently a master of disguise, or perhaps she was several distinct people. She wasn't telling.

Black Orchid wasn't exactly a weird or mystical hero (as far as we can tell from her 70s adventures); she makes my list of supernatural do-gooders only by association. She was a backup feature in the Phantom Stranger's comic toward the end of its run, and she subsequently appeared in tandem with DC's supernatural heroes (Stranger, Deadman, Zatanna) in the years that followed, finally ending up on the membership rolls of Justice League Dark.

See also: Follow Me into Weird Worlds: DC's The Phantom Stranger

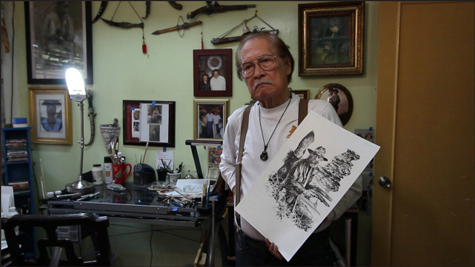

One of the more interesting things about those early adventures was that they were drawn exclusively by Filipino artists—starting with Tony DeZuniga, and continuing with Fred Carrillo and Nestor Redondo—all bringing a cinematic realism to the stories. DeZuniga was the co-creator of the Black Orchid (he also co-created Jonah Hex, and over the years would draw nearly every major character at DC and Marvel). The prolific artists in the Philippines, including Alex Nino and Gerry Talaoc, dominated DC's eerie titles during the early to mid-Seventies and defined a kind of look for that genre.

Black Orchid's foes were always the terrestrial variety, real-world thugs and no-goodniks running extortion schemes and robbery heists. In her first outing in the Phantom Stranger's back pages, she took down a modern pirate running a mining operation with slave labor. The twist to the story is that the Black Orchid is also on the island, incognito, and the pirate assumes she must be the wife of one of the workers he shanghaied into digging in his mine. When the most likely woman runs into the forest and the Black Orchid comes flying out, the mystery seems all but solved—until the woman comes running back out of the forest as the Orchid rounds up the last of the bad guys. Readers are back to square one, no closer to the character's origin or alias. It's a game that the writers would play in almost every Black Orchid story.

In another story, a criminal mastermind, who uses a sizeable computer to help plot his crimes, asks his electronic brain who or what the Black Orchid could be. The computer comes up with four possibilities:

- She is an alien.

- Her powers are actually the result of mass hypnosis.

- Her powers are elaborate special effects.

- She is a ghost.

In the 80s, the first Blue Devil annual would continue the fun, with various heroes sharing the rumored Black Orchid origins they heard, all of which are parodies of Marvel heroes: She was pricked by an irradiated plant, she was doused in radioactive goo after saving a blind man from an oncoming car, etc.

In a multi-parter that ran in the final issues of the Phantom Stranger’s 70s series, an adventuresome heiress named Ronnie Kuhn decides to dress up like her idol, the Orchid, and have some fun, only to be recruited by an organization of women who all have the same idea. They reveal that THEY are the Black Orchid, all five of them—the superhero was never one single person. Thus the mystery is explained, until the last chapter.

In a multi-parter that ran in the final issues of the Phantom Stranger’s 70s series, an adventuresome heiress named Ronnie Kuhn decides to dress up like her idol, the Orchid, and have some fun, only to be recruited by an organization of women who all have the same idea. They reveal that THEY are the Black Orchid, all five of them—the superhero was never one single person. Thus the mystery is explained, until the last chapter.

The Orchid collective is in fact a gang of crooks, looking for a patsy to take the fall for their bank break-in—only the scheme is of course thwarted when the REAL (individual) Black Orchid shows up. As for Ronnie, when the bad guys are put into paddy wagons, the cops all thank her for saving the day. She insists that she's not the real hero, but they all smirk and say, sure, don't worry, we'll keep your identity a secret.

It was one of comics' greatest modern writers who ruined the fun. Best-selling author Neil Gaiman's first work for DC Comics—before he became a fanboy god with The Sandman—was a Black Orchid mini-series, with amazing art by David McKean. While the look of the issues was spectacular, the writing was dire, and Gaiman gave the Orchid an origin that seemed solidly at odds with the earlier stories.

It was one of comics' greatest modern writers who ruined the fun. Best-selling author Neil Gaiman's first work for DC Comics—before he became a fanboy god with The Sandman—was a Black Orchid mini-series, with amazing art by David McKean. While the look of the issues was spectacular, the writing was dire, and Gaiman gave the Orchid an origin that seemed solidly at odds with the earlier stories.

Now, she was a kind of half-human, half-plant clone created by a botanist who sought to save his abused (and eventually murdered) friend Susan. When one Orchid died, a new one blossomed with the old one's memories. How this produced a hero with powers like Superman instead of those like Poison Ivy was never explained. Instead, we saw the latest Orchid fly around and meet up with various other DC heroes. There was no conflict, and the most interesting (yet also annoying) character was Susan's abusive ex-husband Carl, the killer who spouted Sinatra lyrics as he went about his dirty business before being iced almost accidentally.

Gaiman's completely missing the point would be replicated decades later by another very talented author; this time, Jonathan Lethem, on another mysterious hero-without-an-origin series from the 70s—Marvel's Omega the Unknown.

The moral of the story: No matter how gifted a writer is, some comic book loose ends should be left that way. As every stripper knows, the tease is always better than the full reveal. Black Orchid was intriguing only because the readers didn't know anything more than the bystanders who saw her flying overhead.

So far, I've celebrated ambiguity with two DC heroes, Black Orchid and the Phantom Stranger. While both of these heroes were enjoyable because the details about them (when they existed at all) were so murky and enigmatic, there were other heroes who thrived on long examinations of who they are and how they came to be.

The greatest examples of this were the stories that Gaiman's fellow Englishman Alan Moore wrote in the 80s for an also-ran supernatural hero who shared his origins with DC's weird hero boom of the early 70s—the same spawning that gave Phantom Stranger his own series and saw great sales for titles like House of Secrets and Witching Hour. That hero was the Swamp Thing, and his early tales were masterful combinations of super-heroics and horror which we shall examine next.

Check back in 2 weeks as we highlight another DC superweirdo—The Swamp Thing!

Hector DeJean can frequently be found in comic stores, bookshops, and the Eighties. His serialized story of a private detective who only solves food-related crimes is no longer online.