In the near future, the female birthrate drops below 1 percent. It happens within a matter of years, and scientists worldwide are dumbfounded as to the cause. Panic ensues.

Civil war follows shortly thereafter, and America becomes a battlefield between a government research agency that will stop at nothing to find a cure and the citizens who are willing to fight for their civil rights.

Fast-forward twenty-five years. A group of young women are being kept in a remote, high-security facility. They are told it was discovered that a virus caused the lack of female births and that the virus became lethal to humans in the years following the “Dearth,” as it was called. Beyond their protective walls is a dangerous wasteland, and they are humanity’s last hope.

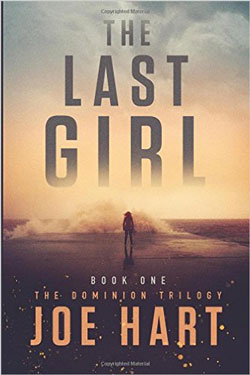

This is the premise for my latest novel The Last Girl—the first book in a dystopian thriller trilogy.

Now, as bleak a concept as the story is, at heart I’m a romantic realist. Hear me out.

It’s possible the trick is putting on the glasses that mesh black and white into more of a gray. I don’t believe there’s ever been a side that was completely right in any arena—political, social, you name it. There are always two sides to a story, and usually equal credit or blame can be found if you look closely enough.

It’s possible the trick is putting on the glasses that mesh black and white into more of a gray. I don’t believe there’s ever been a side that was completely right in any arena—political, social, you name it. There are always two sides to a story, and usually equal credit or blame can be found if you look closely enough.

Is the world a perfect place? Absolutely not—you’d have to exchange your gray shades for ones of a more rose-colored persuasion to believe that.

So where does the romantic side come in? I’ll get to that.

Dystopia—basic translation: not good place.

Utopia—pretty much the opposite.

In fiction, dystopias are typically brought on by a disaster or intense decline of society. And, of course, they sadly aren’t limited to books or movies. Dystopias have existed throughout history, for a very long time. Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany are two very citable examples, but let’s not forget that dystopias still exist today, albeit in different degrees.

One could argue the African country Eritrea could qualify, since media freedom is almost completely controlled by the government—or perhaps North Korea could be included, since its citizen’s political, economic, and even travel are all managed by the state.

But the most interesting question is:

How do dystopias come to be?

I would say two things have always been crucial in forming a dystopia in the real world.

Hope and fear.

Hope? What? Are you crazy? Maybe, but that’s not the point. The point is human beings, as a species, have always strove to make forward progress.

Look at how far we’ve come since the first tool was formed. Despite the fact that the first tool may very well have been a club to bludgeon a fellow person’s head with, as a species we’ve always hoped for the future—a better place for ourselves, our children, and their children’s children. We’ve fought for this, both on battlefields and in courtrooms.

Hope can be a very good thing, but it’s also extremely powerful, and in the wrong hands, it can become toxic. Charismatic dictators have used the masse’s hopes and dreams to further their own power—used it to destroy, plunder, and warp a society into something unrecognizable, because people want to believe that they’re heading for a utopia. The fear of things getting worse is there alongside the hope in the first stages, while later, when control has been lost, it keeps those who dreamed of something better in chains.

A dystopia doesn’t require an enormous breakdown of society or a catastrophic disaster. It needs people to be desperate to make the coming days better than the ones before, along with a leadership that has ulterior motives. Now, that’s not to say there aren’t misguided and downright evil people amongst the populous, who only want to see others suffer or to cause hardship. There will always be those who yearn for destruction, but here’s where the romantic part comes in:

I keep my ideals, because in spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart. –Anne Frank

I believe that Anne Frank wrote the most fundamentally beautiful sentence in human history. Despite everything she had gone through and endured, she still believed in humanity and that, deep down, every one of us is capable of kindness. We are of an age of technology, one in which a person on one side of the world can speak to another with the touch of a button, and I think this is a very good thing because connection creates understanding, and understanding breeds empathy, while defeating fear.

I can’t predict the future. I don’t know what is to come, but I do know that dystopias are real. They’re a single disaster, a genetic anomaly, maybe even a misguided dream away. But the romantic in me thinks that we’re striving for something better, no matter if we fail here and there. We want a utopia or as close to it as we can get. Hopefully, we’re headed in that direction, and someday we’ll achieve it.

And maybe then, dystopias can remain in the fictional world for good.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Joe Hart was born and raised in northern Minnesota. Having dedicated himself to writing horror and thriller fiction since the tender age of nine, he is now the author of eight novels that include The River Is Dark, Lineage, and EverFall. The Last Girl is the first installment in the highly anticipated Dominion Trilogy and once again showcases Hart’s knack for creating breathtaking futuristic thrillers.

When not writing, he enjoys reading, exercising, exploring the great outdoors, and watching movies with his family. For more information on his upcoming novels and access to his blog, visit www.joehartbooks.com.