I just watched Monte Hellman’s moody 1971 road movie Two-Lane Blacktop for maybe the fifth time. After being dazzled by the film once again, I asked myself, because there are numerous qualities that make the movie such a keeper for me, via which winning aspect do I begin?

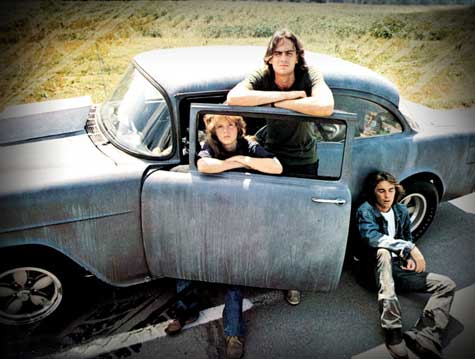

Makes sense to start with the storyline, which is compelling. Written by Rudolph Wurlitzer and Will Cory, the tale is of a cross-country car race. One entrant is a team of two young men who don’t seem to do much in life except roar around in their custom-made Chevy, looking for someone stupid enough to challenge them to a sprint. The other is a lone wolf who zooms around in a GTO, and whom also appears to be at mostly loose ends in life. The two cars and their occupants keep encountering each other on the highways and at roadside places, as they wander through parts of California, Arizona and New Mexico. Finally, after some attitude exchanges on the road and some lippy chatter at a service station, they decide it’s time they shut up and put up: they’re going to race all the way to Washington, D.C. And the winner gets the other’s ride.

The next facet of Two-Lane Blacktop worth commenting on is its atmosphere. Hellman is a film director who is a master of creating cinematic mood, and this feature may be his finest moment of exhibiting this skill. The deep tones of the film are created by things like beautiful shots of various parts of Route 66 (the actors and crew were living the characters’ road trip) and off-road places like cafes and gas stations. The characters’ personalities and their conversations (more on all of that in a few) also add dense notes to the movie. And there’s the overall, existentially penetrating feeling of constant movement that doesn’t seem to have much purpose, yet is necessary. It’s a glorious film to just look at, and to feel.

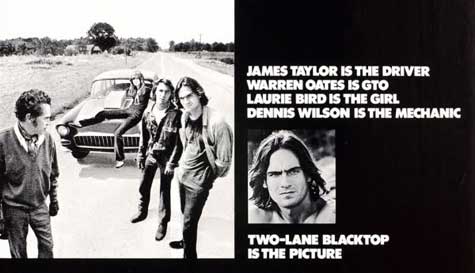

Then there are the characters. There are four main players (none of whom have actual names that are ever used in the film) and while each of the actors representing them adds an important piece to the film, one of them is the clear standout performer. Warren Oates is “GTO,” the solo driver who takes on the younger fellas in the big race. Named after the type of vehicle he cruises around in, GTO is a gregarious dude who’s happy to pick up any random hitchhiker needing a lift, who has a different (and always questionable) life story to tell anyone who cares to hear him talk, yet who is ultimately lonely. Oates is convincing in showing the character’s easygoing/sad duality. Hellman is the brains and eyes behind the camera of the movie, but on the screen this is Oates’s show.

Then there’s GTO’s two-headed nemesis. And what’s interesting here is that while Oates was already a seasoned thespian by the time the film was made, for these other two roles Hellman brought in non-actors. Musicians James Taylor and Dennis Wilson portray “The Driver” and “The Mechanic,” respectively. Taylor plays a sullen young man who doesn’t have much use for words – either saying or hearing them – but who loves to race his machine. Wilson’s character is a comparatively easygoing grease monkey with a hearty laugh and a knowing hand under the hood. While Wilson comes off as relatively natural in carrying out his part, Taylor is a little wooden, and often stumbles over lines; yet this awkwardness in Taylor works for his character, who’s a clumsy sorta guy. As a tandem, Taylor and Wilson function together in a quirkily harmonious way.

The other role, that of “The Girl,” is played (most effectively) by Laurie Bird. She is a freewheeling, wayward young woman who’s a kind of streetwise hippie. She wanders onto the scene, forces her company on the two young guys, and winds up joining in on their race/journey. She goes back and forth between being free-loving and having sudden eruptions of dark moods, her character offering some of the same kinds of personality layers as that of Oates’s. Bird herself was an enigma, and her presence adds some mystique to the film. She only acted in two other movies: Hellman’s Cockfighter (1974) and Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977). (That’s a hell of a trifecta!) Sadly, Bird committed suicide in 1979, at age 25.

Esquire Magazine called Two-Lane Blacktop the film of the year for 1971, and ran its screenplay in their pages. But the movie failed at the box office. Hellman says its distributor Universal didn’t promote it enough; his impression was they just didn’t like it much. It’s such an offbeat film that I don’t know if it was ever meant to be a blockbuster smash to be enjoyed by the masses. But for those of us who can appreciate a grainy, mood-driven road movie, it’s a stone classic.

Brian Greene's short stories, personal essays, and writings on books, music, and film have appeared in more than 20 different publications since 2008. His articles on crime fiction have also been published by Crime Time, Paperback Parade, Noir Originals, and Mulholland Books. Brian lives in Durham, NC with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, their cat Rita Lee, and too many books. Follow Brian on Twitter @brianjoebrain.

See all posts by Brian Greene for Criminal Element.