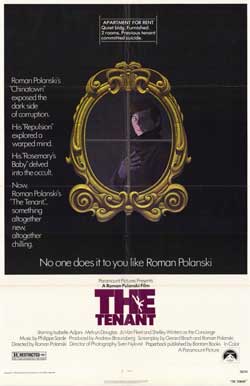

One could reasonably expect that if a Criminal Element blogger were going to single out a Roman Polanski film for appreciation, the chosen title would be Chinatown (1974). But at the risk of committing sacrilege in the eyes of my fellow cinephiles and while I certainly appreciate the brilliance of Polanski’s classic work of film noir, a couple other cinematic works of his have always worked for me in bigger and deeper ways. One of those is his debut full-length feature: 1962’s Knife in the Water, the taut drama about a bourgeois couple who takes a nonconformist young man on a boating excursion. Another of my favorite Polanskis, and the one I’m about to discuss here, is 1976’s The Tenant.

I’ve just been watching the movie again, this being my fourth or fifth viewing. Before I dusted off my DVD, though, I sought out and read the novel from which the story originates. Although I’ve been an avid fan of the film since I first took it in decades ago, I had never before considered whether it was based on a book. I figured I should learn about that before writing this article, and now I’m glad I had the notion. The Tenant is indeed based on a novel of the same title and was written by Roland Topor and originally published in either 1964 or ’66, depending on the reference you’re checking. The book is a strong work – an absurdist, hallucinatory tale that combines nightmarish elements with black humor and which has a penetrating philosophical framework. Topor was an interesting guy: a writer, visual artist, filmmaker and actor who specialized in surreal works. I’ve been reading some of his other stuff since polishing off The Tenant. His books are something like Alfred Jarry’s Ubu plays mashed with Franz Kafka’s The Trial.

The psychologically suspenseful story of The Tenant is basically about identity, and more specifically what happens to a person who starts to lose their grip on their own sense of self. The tale is set in Paris and centers around a timid, overly polite youngish man named Trelksovsky (played by Polanski himself), who is a French citizen of Polish descent. At the outset of the story, Trelkovsky, who works in some clerical capacity in an office, is a man in need of new digs. He goes to check on an apartment he’s heard might be available. At the building he finds the concierge (played by Shelley Winters, whose character always looks like she needs to wash her hair) openly hostile and the landlord (Melvyn Douglas) standoffish. The security deposit is astronomical and the two-room unit doesn’t even come with its own toilet. Yet all of that is trivial business compared to the bomb that gets dropped on Trelkovsky when he learns just why the flat might be open: the young woman who had been living in it attempted suicide, threw herself out of a window in the apartment and landed on a glass overhang structure down on the courtyard level. She is currently in the hospital, in critical condition.

The cranky and heartless concierge assures Trelkovsky that the woman won’t be coming back to the building, but before he signs a lease the humble and bumbling man feels compelled to visit the lady, Mlle. Choule, in the hospital. He grabs a sack full or oranges as a gift and heads to the clinic to pay a courtesy call and to check on her condition. But if he’d been hoping to get his conscience eased via this drop-in, the opposite happens. Trelkovsky is horrified to find Mlle. Choule bandaged from head to foot and missing a front tooth. She doesn’t recognize her friend who is also there to visit – her homegirl is a freewheeling, ever-horny young woman portrayed by a tarted-up Isabelle Adjani – and, if all of that isn’t disturbing enough, the barely-hanging-on patient lets out a series of spine-chilling moans and screams while the two peer at her in her hospital bed. Not long after this night, she dies.

So, um, yeah, the apartment is definitely available. Freaked out though he is by what became of its last occupant, Trelkovsky knows how hard it is to find a place in the city and he takes the flat. And then things start getting really weird. Anyone who’s read some of my other posts here knows that I don’t like to go too deep into describing the developments of the books and movies I write about, as I don’t like to feel as if I’m ruining potential surprises for people who haven’t read or seen the work under discussion. So I won’t start describing all that happens to Trelkovsky after he moves into the apartment. I’ll just say that his life becomes a bad waking dream, one in which nearly everyone he encounters is either hostile to him and/or seemingly attempting to push him into some self-harming act. His neighbors torment him, strangers pick on him, and even those who are sympathetic to his difficulties act in ways that make things even harder for the stricken man.

Polanski and co-screenwriter Gerard Brach were faithful to Topor’s novel. It feels like they simply broke the book down chapter by chapter and said, “Ok, how do we represent each of these segments in a motion picture?” One element of the story that you get a feel for in the movie via some crazed dialogue per Trelkovksy, but that goes much deeper in the book, is a study of the workings of the main character’s increasingly troubled brain. Topor lets us witness the fractured thought patterns of his story’s disturbed protagonist. But then Polanski, ace filmmaker that he is, found a way to take what is a highly cerebral story and turn it into an engrossing feature film. And he added nice little touches, like in the bizarre and hilarious scene where Trelkovsky and Mlle. Choule’s trampy friend go to a movie not long after the horrific scene at the hospital. Polanski has it that they see a Bruce Lee picture, and the juxtaposition of the scenes of Lee slapping around his wannabe foes, with those of Trelkovsky and his sudden lady-friend feeling each other up as they watch, is just too good.

Polanski and co-screenwriter Gerard Brach were faithful to Topor’s novel. It feels like they simply broke the book down chapter by chapter and said, “Ok, how do we represent each of these segments in a motion picture?” One element of the story that you get a feel for in the movie via some crazed dialogue per Trelkovksy, but that goes much deeper in the book, is a study of the workings of the main character’s increasingly troubled brain. Topor lets us witness the fractured thought patterns of his story’s disturbed protagonist. But then Polanski, ace filmmaker that he is, found a way to take what is a highly cerebral story and turn it into an engrossing feature film. And he added nice little touches, like in the bizarre and hilarious scene where Trelkovsky and Mlle. Choule’s trampy friend go to a movie not long after the horrific scene at the hospital. Polanski has it that they see a Bruce Lee picture, and the juxtaposition of the scenes of Lee slapping around his wannabe foes, with those of Trelkovsky and his sudden lady-friend feeling each other up as they watch, is just too good.

One thing I love about both Topor’s book and Polanski’s film is that in that both of them, the reader/viewer is left to decide for themselves whether Trelkovsky is a man who was simply predestined to have some kind of mental collapse, or if he’s being forcibly pushed in that direction by venomous acquaintances and strangers. I also appreciate the way that both writer and movie-maker perfectly blend acute horror with effective humor – not the easiest thing to pull off.

The Tenant is considered to be the third and final installment of Polanski’s spread-out “apartment trilogy,” which also includes Repulsion (1965) and Rosemary’s Baby (’68). In all three movies, the maestro showed himself to be a master of exhibiting psychological terror as experienced by a victimized person. For me, The Tenant is where he most artfully utilized this talent.

Brian Greene's short stories, personal essays, and writings on books, music, and film have appeared in more than 20 different publications since 2008. His articles on crime fiction have also been published by Crime Time, Paperback Parade, Noir Originals, and Mulholland Books. Brian lives in Durham, NC with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, their cat Rita Lee, and too many books. Follow Brian on Twitter @brianjoebrain.

See all posts by Brian Greene for Criminal Element.