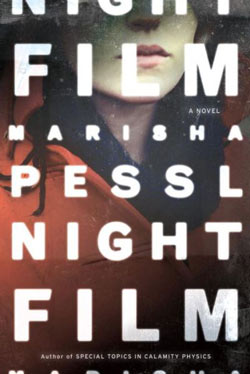

Night Film by Marisha Pessl is a literary thriller featuring a journalist investigating the death of a young woman, the daughter of a cult-horror director who hasn't been seen in public for decades (available August 20, 2013).

Night Film by Marisha Pessl is a literary thriller featuring a journalist investigating the death of a young woman, the daughter of a cult-horror director who hasn't been seen in public for decades (available August 20, 2013).

One of Elmore Leonard’s ten rules of writing says: “Don't go into great detail describing places and things.” It’s followed by: “Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.”

Long-winded descriptions about places and things and people in books are exactly the sections I tend to skip. It’s usually because I’m eager to get to the action or the descriptions are bland clichés (crooked smile, anyone?).

But in Marisha Pessl’s Night Film, the author not only managed to make me not skip her descriptions, she amused me with many of them. The thriller is about a disgraced journalist named Scott McGrath seeking the truth behind the death of a reclusive cult director’s daughter. Authorities believe she jumped to her death, but McGrath thinks she may have been driven to it by her father, whom McGrath has compared to Charles Manson when it comes to the influence he has over his fans and followers.

The first description that caught my eye came early on in the book, when the divorced McGrath mentions the nanny his ex has hired to take care of their five-year-old daughter:

Her name was Jeannie, but no sane man would ever dream of her.

There are no physical descriptions of Jeannie besides the fact she’s twenty-four years old, but that line tells me enough. It makes the point that how one character feels about another is sometimes more important than what the other person looks like.

In another scene, McGrath walks into a hotel and approaches the coat-check girl:

“Good evening, sir,” she said brightly, removing her glasses, revealing big blue eyes and delicate features that would have made her an “it girl” four hundred years ago.

The girl is also described as scrawny and 5’7” with pale blond hair, but this one line helped me fill in the rest of her appearance with my own mental images of what an It Girl from four hundred years ago would look like.

Later, McGrath talks to someone who knew Ashley Cordova, the director’s daughter, before she died. The guy, Hopper, says they’d met at a camp for troubled kids, and describes how his uncle got Hopper to the camp after Hopper ran away:

“Hired some goon to track me down. I was crashing at a friend’s in Atlanta. One morning I’m eating Cheerios. This brown van pulls up. If the Grim Reaper had wheels it’d be this thing. No windows except two in the back door, behind which you just knew some innocent kid had been kidnapped and, like, decapitated.”

I didn’t need to know anything else about that van, which model or year or how shiny it was. It was clear that if a van like that pulled up next to me, I’d run like hell.

Hopper joins McGrath’s search for the truth about Ashley’s death, and they visit someone who worked as a security guard at a mental hospital where Ashley was a patient. They approach the man’s house with some trepidation, and McGrath tells Hopper to look through the window to see what the people inside are watching on TV.

“We’ll be able to tell what type of people we’re dealing with. If it’s hardcore Japanese anime, we’ve got problems. But if it’s a Barbara Walters special—”

“It looks like a rerun of The Price Is Right.”

“That’s even worse.”

Before McGrath and Hopper knock on the door, I was already scared of whoever was on the other side. Who watches The Price Is Right at night? And a rerun? Pessl’s choice to describe these people by their TV habit is effective and clever.

McGrath also has this to say about his short-lived affair with a former research assistant:

Making love to Aurelia was like rummaging through a card catalog in a deserted library, searching for one very obscure, little-read entry on Hungarian poetry. It was dead silent, no one gave me any direction, and nothing was where it was supposed to be.

Even though I love being in libraries and find them romantic, this description got the point the across that McGrath’s experience with Aurelia was anything but. I found it amusing that pleasing her was tantamount to locating an obscure Hungarian poetry book, with no guarantee that if McGrath found the book he’d be able to understand it, or if Aurelia would offer to translate. Doesn’t that sum up how communications are between men and women sometimes?

Night Film is full of descriptions like this, observations that are witty and sharp and contain instantly recognizable elements of truth. The plot is dark and mind-bending, but it’s always clear that Pessl knows what she’s doing, and she’ll make you want to read all the words on all the 600+ pages of this book.

To learn more or order a copy, visit:

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]() opens in a new window

opens in a new window![]()

Elyse Dinh-McCrillis is a freelance writer/editor who likes soup and the Bee Gees, often at the same time. She also blogs at Pop Culture Nerd and tweets as @popculturenerd. She edits crime fiction as The Edit Ninja.

I won an ARC of this book and I can’t wait to read it. I’ve received several e-mails saying how good it is. I love that. Gives me a rush!

Start it now! Hope you like it, too!

Many emails have been sent to me praising it. I adore it.