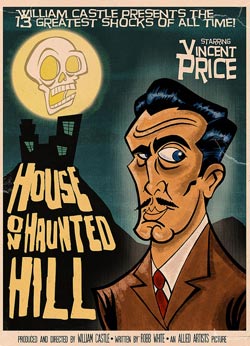

Just to be crystal clear, we’re talking about the original now. Not the slick, overblown, CGI-laden 1999 affair. Yes, we’re all about the real deal here: the half-a-century-old public domain classic, the one starring Vincent Price, the inarguably authentic version—House on Haunted Hill, the 1959 model.

Just to be crystal clear, we’re talking about the original now. Not the slick, overblown, CGI-laden 1999 affair. Yes, we’re all about the real deal here: the half-a-century-old public domain classic, the one starring Vincent Price, the inarguably authentic version—House on Haunted Hill, the 1959 model.

The film was directed by William Castle, the B-picture horror impresario who gave the world The Tingler and 13 Ghosts. Castle was the master of movie house gimmicks such as “fright breaks” and “coward certificates.” For Haunted Hill, he boasted a technique called “Emergo” in which a fake skeleton, attached to a wire, darted over the audience’s heads at a pivotal moment. Now, that’s entertainment.

Actually, the film’s low budget is one of its charms. The props at times have a bargain basement look; the plot has some holes you could drive a hearse through, and the spooky soundtrack is basic Boo Baroque. And it’s all just great, rendered in deathly black-and-white. (Steer clear of any colorized versions; stick with the original two-toned palate, which serves the atmosphere well.)

From the get go, the film delivers. First we get the weird, twitchy character Watson Pritchard—or, more specifically, his disembodied head—breaking the fourth wall to tell us how screwed we are: “The ghosts are moving tonight, restless, hungry…. Seven people, including my brother, have been murdered in it. Since then, I've owned the house. I only spent one night here and when they found me in the morning, I was almost dead.” Swell.

From the get go, the film delivers. First we get the weird, twitchy character Watson Pritchard—or, more specifically, his disembodied head—breaking the fourth wall to tell us how screwed we are: “The ghosts are moving tonight, restless, hungry…. Seven people, including my brother, have been murdered in it. Since then, I've owned the house. I only spent one night here and when they found me in the morning, I was almost dead.” Swell.

Pritchard is played with agitated flourish by Elisha Cook, Jr., who in his time was the very definition of Character Actor. In the course of fifty-plus years, the diminutive, wide-eyed Cook racked up over two hundred roles, his break-out turn being the “gunsel” in Maltese Falcon.

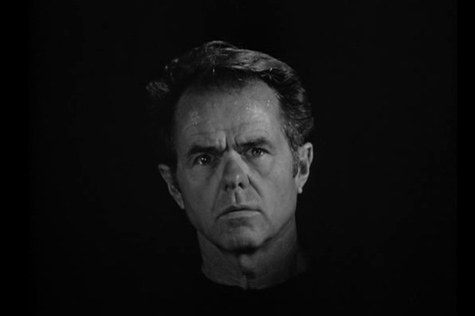

After offering his gloomy account, Pritchard is replaced by Frederick Loren (Vincent Price), also disembodied. Loren, the wealthy renter of Maison Hantée, explains to us the structure of the evening (and the movie): it’s a party! Loren has invited five strangers who’ll each receive $10,000—with the caveat that they must spend the night in the ghost-ridden house after the doors are locked at midnight. Should any party-goer perish during the festivities, their next of kin will receive his or her portion. (Apparently, Mr. Loren is a champion of equitable business practices.)

Then we cut to a shot of five funeral cars winding up the driveway (one of many nice touches by the perpetually bemused host) and hear Loren’s pithy little bios of each guest. We get our first full look at the mansion’s odd, blocky exterior. (Fun fact: it’s actually the Ennis House, one of fabled architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s works based on the design of Mayan temples, also used famously in Blade Runner. ) Once we finally enter the building, it’s pretty obvious that the interior and exterior don’t quite match, but, hey, who cares? It’s all good.

Amid the house’s fine furniture, sculptures, and overwrought cobwebs, the guests trade introductions, and Pritchard—the homeowner, but also one of Loren’s cash-seeking invitees—immediately harshes the vibe. In his depressive, delightful way, Pritchard describes the grisly aftermath of one of the house’s many previous murders: “We found parts of their bodies all over the house, in places you wouldn't think. A funny thing is, the heads have never been found. Hands and feet and things like that, but no heads…. You can hear them at night. They whisper to each other, and then cry.” Sprawled on the living room floor in my pajamas, my kid-self shivered at Cook Jr.’s evocative little speech. Severed ghost heads whispering and weeping? Damn! That was unnerving stuff.

Soon, their well-heeled host appears, and things really amp up. Ah, Vincent Price…

For sheer, unadulterated, melodramatic flair, he was unmatched. The scion of a cream of tartar dynasty (look up Dr. Price's Phosphate Baking Powder!), Price was known professionally as the penultimate villain, but personally as an urbane, devoted connoisseur of art and fine food. The man, like his characters, was staggeringly suave.

Here, Price portrays Frederick Loren with a smooth, sinister panache that drips smugness and venom. In a neat trick, the performance is both over-the-top and restrained. Particularly appealing are his scenes with the quirkily lovely Carol Ohmart as Loren’s trophy wife and partner in verbal prizefighting. Their exchanges play like a pulp version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. And I say that with respect.

Here, Price portrays Frederick Loren with a smooth, sinister panache that drips smugness and venom. In a neat trick, the performance is both over-the-top and restrained. Particularly appealing are his scenes with the quirkily lovely Carol Ohmart as Loren’s trophy wife and partner in verbal prizefighting. Their exchanges play like a pulp version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. And I say that with respect.

The film’s premise firmly established, the story whizzes on with breezy abandon. There are lots of good garish bits: revolvers in tiny coffins, vats of acid, blood-dropping ceilings, and Pritchard’s constant downers, such as: “Only the ghosts in this house are glad we're here.” As for the aforementioned plot holes, my younger self was unaware of them, and my older self forgives them. Sure, now reflecting on what for me has always been the movie’s most iconic scene—the ingénue’s encounter in the closet—I find myself asking, “Since when do blind people cross a room by gliding?” I don’t need an answer to that; I really don’t. Just as I don’t need a skeleton diving over my head to appreciate the timeless wobbly wonders of Haunted Hill.

Note: While this movie isn't strictly a Crime Against Film, it seemed only fitting to place its entry respectfully among its artistic progeny.

Michael Nethercott is a playwright and writer of traditional mysteries whose O’Nelligan and Plunkett tales appear periodically in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. His first novel featuring this 1950s detective duo, The Séance Society, will be released in October, 2013 by St. Martin’s Press.

RKO Fordham on Fordham Road in the Bronx. You say it was 1956? I would have been ten. The poor skeleton on a wire that glided out above the audience nearly to the center of the theatre was in the unfortunate position of gliding over the children’s section. We screamed like banshees and threw everything we had at Old Mister Bones: candy, popcorn, soda, food wrappers. The matron almost had a heart attack and it wasn’t because of the movie.

Sorry to mislead, Terrie. The ’56 date in the text should actually read 1959 (as is properly noted in the essay’s title.) The site’s editor will be correcting that fairly quickly. So… you would have been 13 when the film came out — still justifiably young enough to scream like a banshee and hurl edibles at skeletons.

Michael, That works. We were forced to sit in the children’s section until we were 16. At 13 I was strong enough to hurl Good and Plenty candies far and high and hit the skeleton in the head. Or at least come really, really close. (Okay, okay, I’ll stop bragging now. LOL) Thanks for a terrific post.

What a great look back. I’m old enough to have seen the original movie in the theater…and like you, I’ve never forgotten the experience. I remember the expectation of something “coming out” (we didn’t know what) at any moment to scare us in the audience was just as much fun as the movie itself ? Thanks

I saw this at a VERY young age at our local drive-in theatre (missed the skeleton, darnit–the drive-in didn’t have a way to rig it). I don’t remember being scared, but then I was usually the one who had to/got to stay up with our babysitter when she wanted to watch Shock Theater on Friday nights but didn’t want to be awake in the house alone, too!

Michael, why is the video in your blog unavailable? YouTube never says why they delete certain videos. I would like to know why. Please respond to my comment here.

Margaret,

I don’t know why that particular video was removed, and I honestly don’t remember what it was. The blog page is eight years old. The essay was mine, but the pictures and videos were chosen by the site manager.

Michael