Russ Meyer said that when people watched his movies, he wanted them to know “where they are” five minutes into the viewing (umm, you achieved that, Russ). Orrie Hitt may or may not have expressed that same desire concerning the experience readers had poring over his novels, but he wrote like he wanted that to happen. You always know “where you are” in a Hitt novel.

Or do you?

Meyer and Hitt, although masters of two different media, had many other things in common as artists, besides the immediacy of their works. Primarily, they both achieved a rare duality of both embracing and transcending the possibilities involved in producing exploitation fare. On one level, Meyer’s films were just celluloid excuses for a big tits-obsessed guy to have his female characters’ huge jugs bouncing all over the screen. Similarly, in Hitt’s novels we never get too far from the matter of sex – characters are pretty much always either having it, talking about it, longing for it, or suffering some kind of repercussion as a result of it . . . and Hitt clearly loved writing about it.

But whereas many can make a titillating (pun intended) softcore film or write a steamy pulp novel, there are things in these two men’s work that set them apart from the sleazy pack. They were both visionary artists. Laugh at me for making this claim if you want, and I’ll laugh right back while knowing I’m right. There is genius behind Meyer’s dizzyingly abrupt film cuts, and in his outrageously over-the-top characters. With Hitt, the artistry has to do with his uncanny ability to capture a certain corner of the human experience, and to write novels that flowed seamlessly while being effective on different levels simultaneously. Outside of all the hanky panky, Hitt’s books are simply ultra-realistic, gritty, often moving human dramas. His characters are so believable that you hate some of them, care about others, and pity many. His portrayals of these peoples’ life experiences are engaging. His tales reel you in on page one and keep you interested throughout.

Like Meyer, Hitt tended to keep things basic with regards to his characters and settings. Many of his male leads sell insurance, fix cars, toil in factories and the like; the women serve customers at greasy spoons, dance in clubs, or take modeling jobs; and many of both sexes are hotel and farm employees. The towns (usually rural New York or thereabouts) depicted in Hitt’s novels are often clearly split between the “good” and “bad” sections, and it’s the latter that generally get covered in the books. Often, there is one particular, shameful street in the burg, where all the prostitution, drug dealing, and such occur, and this is the street where many of Hitt’s characters work and live. Some of his people try to break out of the ghetto while others give in and fully engage in the life there, but few of them bear any illusions about the possibility of a wholesome happily ever after for themselves.

People in the books talk plainly to one another (Hitt was an absolute master at snappy dialogue, and this is a constant source of pleasure in his books). They’re all hot to trot, and if you see somebody who gets you all bothered in your pants, you just tell them so and make a go for it, and this is true of both the male and female characters (and sometimes it’s a woman who gets another woman feeling that way). People hook up and either the guy can be “careful” or they can let go and engage in the act all naturally, then run the risk of the girl getting big in the belly, at which point they can either bring into the world another mouth to feed, or find some way to come up with three hundred bucks to get the situation handled. Likewise, most everybody is out to make a few dollars wherever and however they can, even if it means cheating or exploiting your neighbor, everyone knows this and there is no pretense between them about any of this. Life is broken down into these few basic elements.

One thing that sets Hitt’s novels apart from rank and file exploitation fare is the sympathetic nature of some of them, and social consciousness. His 1966 title Women’s Ward isn’t one of his better-woven stories, yet it’s a great example of the kinds of twin currents that often run in his books. On the surface, the story is about a violent and sex-hungry female psychiatric ward patient. The tale is narrated by a hospital aide who gets involved with that woman, while simultaneously conducting a hot affair with her equally lustful sister on the outside. All through Women’s Ward, though, Hitt uses his narrator’s voice to express great sympathy for the mentally ill; he lashes out at the public’s ignorant misunderstanding of them, and medical professionals’ misdiagnoses of them. Similarly, other books by Hitt contain elements wherein he shows concern for people who are societally disadvantaged in various ways.

One thing that sets Hitt’s novels apart from rank and file exploitation fare is the sympathetic nature of some of them, and social consciousness. His 1966 title Women’s Ward isn’t one of his better-woven stories, yet it’s a great example of the kinds of twin currents that often run in his books. On the surface, the story is about a violent and sex-hungry female psychiatric ward patient. The tale is narrated by a hospital aide who gets involved with that woman, while simultaneously conducting a hot affair with her equally lustful sister on the outside. All through Women’s Ward, though, Hitt uses his narrator’s voice to express great sympathy for the mentally ill; he lashes out at the public’s ignorant misunderstanding of them, and medical professionals’ misdiagnoses of them. Similarly, other books by Hitt contain elements wherein he shows concern for people who are societally disadvantaged in various ways.

Another thread that ties many of Hitt’s books together is the matter of the parents of the main characters. The lead players in his novels – both male and female – almost never have positive parental situations. Either one or both parents is long since dead, or they live far away from their kids, or they’re alive and inhabit the same town and/or home as their children, and they’re just no damn good. An obsessive writer who tended to hammer away at the same themes and situations over and over in his various novels, Hitt clearly had an interest in what became of people who got a raw deal in their upbringing.

Hitt’s books generally end happily, at least for some of the characters, with a few of the people somehow coming through everything still with the hopes of being blissfully married to a person they love, setting up a happy home, and pursuing a life that will see them making a living doing something legitimate. But others don’t fare as well, either landing behind bars or dead in an alleyway. The reader has to guess which characters will wind up on each end of this spectrum, and this is part of the adventure in following the tales.

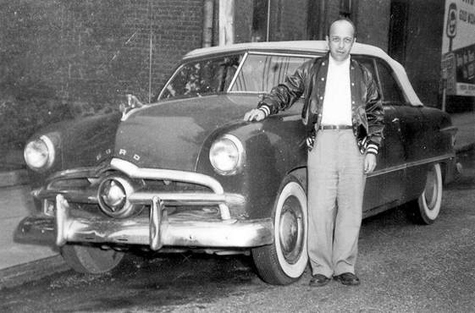

So that’s an overview of Orrie Hitt, the writer. But what about the man behind the books with titles such as Shabby Street, Panda Bear Passion, The Excesses of Cherry, etc.? Hitt’s readers might have been surprised to learn that, while the leading men from his novels are often playas who get lots of girlie action while carefully avoiding nuisances such as wives or children, Hitt (who was known to family and friends as Ed, his middle name being Edwin) was a steady family man. He and his wife Charlotte raised their four children in the small town of Port Jervis, New York.

Hitt was born in 1917 and passed away in ’75. Aside from his writing pursuits, other professions he practiced included: insurance salesman, radio announcer, and manager of a private hunting and fishing club (he used situations and settings from those jobs in many of his novels). Once, to help defray the medical expenses involved for his ailing son, he took a short-term gig managing an airport club in Iceland. Although his pulp novels didn’t start appearing until 1954, he was a published writer as early as his high school years, when an article of his ran in a fishing and hunting magazine (an unsympathetic teacher of his submitted a piece of writing to the same publication and got a rejection, to Hitt’s delight).

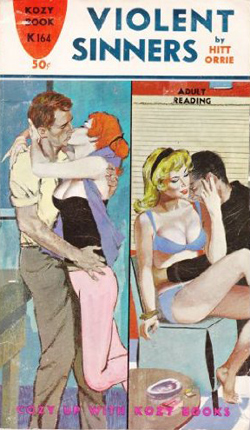

Once Hitt got going with the pulp novels, he pumped out a ridiculously large number of titles. Don’t ask me to count them. His terrain was the world of the paperback original. The covers of his books would make an excellent pulp culture art exhibit. He wrote for outfits such as Kozy Books, Softcover Library, Beacon-Signal, and Domino. Not surprisingly, daughter Joyce remembers that, “His biggest problem was getting his checks from publishers and dealing with his agents.”

“He most always wrote at the kitchen table with his cigarettes and iced coffee, as the furor of life with four children surrounded him,” Joyce remembers now. “At one time he established an office on the second floor of our home and used a dictaphone to dictate stories, which were then typed by someone else. This didn't last long; he came back to writing at the kitchen table and writing full time.”

Nancy Gooding, Hitt’s youngest and his other surviving child, tells, “I loved the sound of the typewriter clacking day and night when his thoughts were all connected to produce an interesting story, and sometimes felt that others were jealous of his intellectual mind and how he ticked.”

On the back cover of the Kozy Books edition of his 1962 novel Violent Sinners, Hitt himself is quoted as saying, “All I do is write. I usually start at seven in the morning, take twenty minutes for lunch and continue until about four in the afternoon.” He also says, in that space, that he is married to a woman “who understands me,” and, “I’m just an average guy.”

As a writer, Orrie Hitt achieved a much-harder-than-it-looks duality of authoring stories that could both satisfy the joneses of readers out for a good lusty tale, and engage someone up for a compelling human drama. As a man? Well, I can only hope that when my two daughters are grown, and if someone mentions my name to them, they will light up the way Joyce Gordon and Nancy Gooding do when you talk to them about their dad.

(Some) Greatest Hitts

Ok, I’ve only read a small fraction of Hitt’s novels – about 30. But here’s a rundown of my favorites from those:

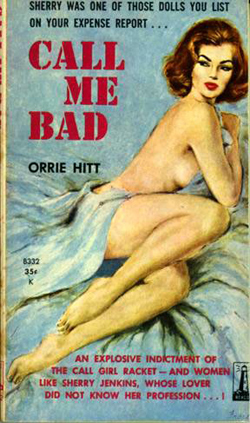

Call Me Bad (1960): Sherry Jenkins and Harry Barnes want to get married to each other. There’s just two pesky things in their way: Harry’s wedded already and Sherry’s a call girl, and both have been hiding these things from each other. Harry’s a traveling beer salesman and Sherry conducts her work on her back at Ma Williams’s notorious Central Hotel. There are other problems for Sherry, like her bum of a father who doesn’t work and who uses money Sherry gives him to buy booze and entertain girls Sherry’s own age. And then there’s the fact that Sherry’s a pretty, well-endowed girl whom guys can just never leave alone.

Call Me Bad (1960): Sherry Jenkins and Harry Barnes want to get married to each other. There’s just two pesky things in their way: Harry’s wedded already and Sherry’s a call girl, and both have been hiding these things from each other. Harry’s a traveling beer salesman and Sherry conducts her work on her back at Ma Williams’s notorious Central Hotel. There are other problems for Sherry, like her bum of a father who doesn’t work and who uses money Sherry gives him to buy booze and entertain girls Sherry’s own age. And then there’s the fact that Sherry’s a pretty, well-endowed girl whom guys can just never leave alone.

Violent Sinners (1962): On the same day that 20-year old Art Lord gets laid off from his factory job, his live-in girlfriend Marie informs him that she thinks she’s pregnant. Marie was already on him about them getting married, and now she’s really going to amp up that pressure. The only work Art can find is the job of general handyman out on an onion farm. The owner of the farm is a 50-year stubborn cuss, who is married to a buxom girl Art’s age. Art has to live on the farm to work there, but he’s not allowed to bring Marie because they’re not married. Oh, and Art learns that the last three guys all left the job after only working on the farm for a short time, and while he doesn’t have the details right away, he gathers that they all bailed because of something having to do with the farmer’s wife. Art’s about to find out what drove the other fellas away.

Wayward Girl (1960): Sandy Greening is a 16-year old high school dropout who looks like sex on wheels. She slings hash at a diner and makes more money selling her voluptuous body to the joint’s customers after closing time. Her dad’s in the pen, her mom’s no good, and her boyfriend is stupid enough to kill a member of a gang that rivals the one to which he and Sandy belong. For a teenager, Sandy has seen a lot. But she’s about to see a whole lot more at the “progressive” reform school to which she gets sent after she’s arrested for hooking.

Dial “M” for Man (1962): One oft-repeated storyline in Hitt’s novels is that of a young, workaday guy getting involved with an equally youthful woman who is married to an old, rich, mean-hearted man (see Violent Sinners capsule above). The guy is an honest type, and smart except when it comes to women, and the girl is sexy and a manipulator. In Dial “M” for Man, an example of this type of story, narrator Hob Sampson is the owner of a TV sales and repair shop. He’d like to expand his business but he needs a bank loan to do that, and he can’t get the loan because he has a personal enemy who sits on his bank’s board of directors. That foe is a 60-year old, dirty-dealing real estate tycoon who has it in for Hob because Hob’s dad once tried to bust up the man’s racket. The tycoon is married to a 22-year old hottie who just happens to have a TV set in need of repair, on a night when she’s all alone in the palatial estate she and her hubby inhabit. Hob makes a house call and things happen, natch. But what’s really at play here? Is she using Hob or is it the other way around? Or could it actually be love between them? Hmmm . . .

This Wild Desire (1964): A good example of a twin-currents Hitt novel. On one level, This Wild Desire is an aching story about a man at a personal crossroads. Brad Norton is (partly) still grieving over his ex-wife, who cheated on him, only to have the other guy kill her, then himself, when she got pregnant by him. Brad owns a small radio station, and while he is knowledgeable and passionate about the business, his outfit is on the brink of collapse due to a dearth of advertising income. When a well-to-do businessman whom Brad covets as an advertiser, invites Brad to an extended stay at his mountain house for some deer hunting, Brad knows he better come away from that excursion with a fat new account. On another level, the book is a sex romp. The prospective client’s daughter and his live-in cook are both bodacious honeys who like the looks of Brad and the feelings are mutual. Throw in a visit from the sweet thing who works for Brad and with whom he has an on-again, off-again love/sex affair, and Brad’s going to have to become wildly efficient if he’s going to be able to make his big sales pitch while tangling with all the babes.

Brian Greene's articles on books, music, and film have appeared in 20 different publications since 2008. His writing on crime fiction has also been published Noir Originals, Crime Time, Paperback Parade, and Mulholland Books. Brian's collection of short stories, Make Me Go in Cirlces, will be published by All Classic Books in late 2013 or early '14. Brian lives in Durham, NC with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, and their cat Rita Lee. Follow Brian on Twitter @brianjoebrain.

I’m not sure why Brian Greene thinks Orrie Hitt was a pulp author: “Although his pulp novels didn’t start appearing until 1954.” Pulps were pretty much dead by the ’50s.

Pulps were magazines, not books. Typically, a pulp was 7 inches by 10 inches and printed on the cheapest paper, pulp (hence, their name). Additionally, pulp was not a genre (indeed, pulp HAD genres: mystery/crime, horror, fantasy, science fiction, aviation, war, adventure, masked vigilantes), but rather it was delivery system. It can’t be pulp unless it was in a pulp magazine. Doesn’t that make sense?

It’s really quite insulting to call books that come out whenever they are finished “pulp” when genuine pulp authors like Walter Gibson published TWO novels a month! He maintained this schedule for decades.

Another pulpateer, Lester Dent, yearned to break out of the pulps and get into publishing books! Mr. Dent would have a few choice words for anyone he heard say that his mystery books were “pulp.”

Mr. Hitt might feel the same way. Additionally, Hitt’s novels contain adult themes you would never find in the pulps. There’s no reason to make sleazy fiction synonymous with “pulp” when Western & romance pulps were more popular and longer lived!

Another point to keep in mind is that what is was described in pulps were generally unrealistic (there was never a real detective like Philip Marlowe!). Mr. Hitt’s books are pretty much true to the real world.

Ignorance of your culture is not considered cool.

Lloyd Cooke

P.S. I recommend Brian read this site called Criminal Element that has featured a new book called BLACK PULP.

Oh, and he doesn’t have to listen to me but maybe he’ll believe Walter Moseley

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/walter-mosley/post_4876_b_3346575.html

@Lovablekook- While technically you’re correct, the fact is that common parlance includes Orrie Hitt in pulps, so while we can argue that every thriller should have a ticking clock or every noir should have societal underdogs, people tend to expand the use of the terms where they find them helpful to capture a certain flavor of reading experience.

Without it being to the ‘t’ precise, I know exactly what people mean who call Larry Block’s pseudonymous softcore paperback career “pulpy,” so I’m not sure, for me at least, it’s a definitional hill worth dying on. Especially given that crime fiction has historically introduced–often to disdain at its vulgarity–loads of slang and grammatical “misusage” into popular vocabulary, it’s not at all surprising its own terms get pretty freely slung around, too.

Can’t agree, Clare. Since when is “technically correct” not correct?

Why be half wrong when you can 100% right?

I’m talking fact, not opinion (“common parlance”).

There was never anything like Hitt or Block’s porn found in the pulps.

Up until now, those were always called “potboilers.”

This distinction is especially imporant at a time when original pulp is being reissued and old pulp characters are in new material!

It’s funny that we live in the Information Age but really in the Misnomer Age.

Would you like some youngster in your family to told that pulp is fun and clean (like The Shadow or Doc Savage) and somehow get paperback porn? No you wouldn’t. If you really cared about pulp, you would do all you could to be clear. By the way, how can anyone here counterance both real pulp being called pulp AND porn also being called porn?

The mark of a Johnny Come Lately in this field is people who call paperbacks “pulp.”

[quote]Pulps were magazines, not books. Typically, a pulp was 7 inches by 10 inches and printed on the cheapest paper, pulp (hence, their name).[/quote]Dude, words change in meaning. That’s what happens to language–it’s a living thing. “Pulp” may have had one meaning when it began, but it’s been far more inclusive than just magazines for ages. Not that I don’t respect the tilting at windmills, because we all do it at times, but there’s no need to get nasty about it.

Who’s being nasty, “dude”? Words change in meaning but that doesn’t absovle a misnomer. Do you think it is good when the creature that brought Boris Karloff fame is called “Frankenstein” when that namer referes to his creator? Do you think your culture is served when Aretha Franklin is called “Motown” when she was never on the label?

There’s no need for Hitt’s novels (and those like them) to be called pulp when there were books just like that before and after pulp. I mean, what is the point? Who’s tilting at windmills when my correction keeps minors from reading what is basically porn?

a) you are being nasty. Your tone is rude and dismissive and patronizing.

b) words change meaning. The word pulp now has a meaning beyond that you narrowly describe. Your meaning has become subsumed into the larger meaning.

c) you’re not keeping kids from reading sexy stories by insisting on an oudated definition. That’s actually not what definitions do.

d) looking at your other comments, I notice this topic is a complete hot button for you and you don’t seem to be able to acknowledge that anyone else might have a different and also correct point of view, so I don’t expect you’ll be able to let this one go, but I have better things to do so I am out. Responding is done.

Rude? How? Where? Facts are facts, whether I point them out or not. Why is my being right somehow not “right”?

Words change meaning but not this time, not here. I’m taking about a misnomer. Pulps are magazines. And Hitt’s books are books. Books exactly like his still get published to this day and get called books. Ask a publishers.

I have no idea what you point c) means. I don’t mean to keep anyone from reading anything. Defining something is not censorship, you know!

Maybe it’s a hot button issue for you. You’re the one insisting on being wrong. Why be wrong when you can easily be right? You can have a different point of view, but it isn’t fact.

@Lloyd Cooke

I’m afraid your definition of pulp fiction is incorrect. You seem to be confusing “the pulps” with pulp fiction. “The pulps” were, for the most part, fiction magazines of the 30s, 40s and 50s that carried adventure, crime, western and romance stories. By stories, I mean short stories, novellas, novelettes and novels. They were denigrated as “pulps,” as opposed to the “slicks,” the better magazines printed on slick paper.

If you were to actually read a wide variety of the pulp magazines, you would know that they published many novels within their pages, some, such as Mercury Mystery Magazine devoted their entire magazine to a single novel. Out of these came the first “paperback originals” by publishers such as Universal who’s first PBOs were digest-magazine size. Within a few years they were being published in 41/4”x6” or 7” size.

Many of the stories printed in installments in the pulps or as complete novels in a single edition were reprinted as paperbacks, most notably Dashiell Hammett’s Maltese Falcon which was serialized originally in Black Mask. It actually sold many more copies in paperback in the 1950s than were sold on the pages of Black Mask. At the time such fiction in paperback was referred to as pulp fiction because of its origins on the pages of the “pulps.” The term pulp fiction appeared for the first time only in the 1950s in reference to several genres of fiction, in any format, that originally appeared in these magazines as noted above. The term “pulps” actually predates these magazines, being used as it was in reference to magazines such as Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang and even back as far as the penny dreadfuls.

Pulp fiction actually reached its peak in the 1950s, bolstered by book sales. Books by the same authors who got their start in the pulps. Magazines such as Black Mask ceased publication in 1952, but another magazine, Manhunt, quickly took its place the following year and lasted until 1967.

You conjecture that Walter Gibson and Lester Dent wouldn’t have referred to the PBOs of the 1950s as “pulp fiction,” but indeed they did. Add to those two names, Frank Gruber, who saw the paperbacks as the natural progression of pulp fiction. The paperback originals were descended from these magazines as they were all published by these same magazine publishers, e.g., companies such as Fawcett and Universal. The concept of publishing original novels in paper came from these magazine publishers, not book publishers.

The one new element to pulp fiction introduced in the 1950s was sex. It was a reflection of the changing morals of the time. The aforementioned Fawcett with its Gold Medal line and Universal with its Beacon Books lead the way. Beacon even introduced an “adult science fiction” line in 1954 with lots of sex.

Orrie Hitt, whose early novels were printed in digest magazine format, was the quintessential pulp fiction writer. He was a hack who at the peak of his career was writing 17 novels a year. Orrie Hitt wrote some good crime novels, but Hitt was a writer who would be overlooked for decades because he fell into the crack between the genres of crime and erotica. Because his best books were written in the 1950s before the eroticism could be explicit, it quickly become outdated by the books in the 1960s made possible by the court victories of the late 50s/early 60s. And the crime in Hitt’s books was not the usual sort of violent crime found in the pulps. More often than not it was white collar crime or victimless crimes such as prostitution.

Orrie is my great grandfather on my Mothers side. Although, my great Grandpa and I never met, I appreciate this article. Thank you for telling the world about him, thank you for telling me about him!