Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him Horatio; a fellow of infinite jest…

In William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the role of Yorick the court jester is little more than a cameo (you couldn’t properly call it a “walk-on”); a nonspeaking role that wouldn’t even qualify you for membership in Actors’ Equity. Yet plenty of people have wanted to play him, even though “poor Yorick” is nothing more than a skull that Hamlet holds and muses upon in Act V, Scene 1.

After all, Yorick is a role you could play…forever.

When pianist and composer André Tchaikowsky died of colon cancer in 1982 at age 46, the provisions of his will were specific: his organs were to be donated to science and his body cremated; all except his skull, which he bequeathed to the Royal Shakespeare Company “for use in theatrical performance.” Although he didn’t specify the role he had in mind, it was clear that Tchaikowsky intended it to be Yorick. But there were obstacles.

The funeral directors hired to cremate Tchaikowsky’s remains refused to decapitate him. They claimed his bequest was illegal, and even after it was determined that Tchaikowsky was within his rights to leave his skull to whomever he chose, they declined to perform the operation. It was done at a local hospital instead.

Even after the RSC had Tchaikowsky’s bequest in hand as it were, they were reluctant to use it onstage. Members of the company who had known Tchaikowsky when he was alive (he was a prominent musician whose last work was an operatic adaptation of The Merchant of Venice) were not keen on handling the skull of their departed colleague. Then there was the risk of damage. Skulls are fragile and irreplaceable. What if something were to befall Tchaikowsky’s skull?

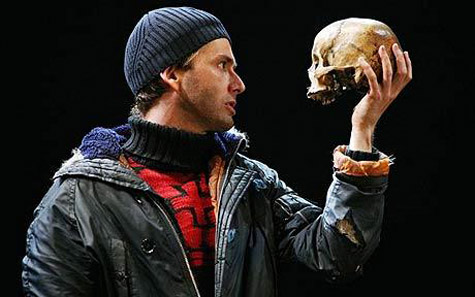

It was a risk no one wanted to take. So the skull was kept in the propmaster’s room, making a brief appearance for a photo of Roger Rees playing Hamlet in 1984 and resurfacing for rehearsals of a 1989 production starring Mark Rylance (an artificial skull was used during performance). Then finally, in 2008, André Tchaikowsky appeared onstage in a production of Hamlet, amid such publicity that he managed to upstage David Tennant in the lead role. At the time, Tennant told the press that he thought Tchaikowsky’s bequest was “brilliant” and that he’d consider doing the same thing. (He can’t now; the laws have been changed.)

A leading Shakespearian actor of the early 19th century, when Cooke was on form, few could rival him, but Cooke wasn’t on form with great consistency. He was known to appear onstage drunk—make that incapacitated. That’s why, when he arrived in the United States in 1810 for his first American tour, audiences didn’t believe they were seeing Cooke perform. The man who played Richard III in New York was stone cold sober. At least for a time. Until he drank himself to death in 1812.

The doctor called to attend Cooke at his deathbed was John W. Francis, a theater aficionado and a noted collector of skulls (for research purposes only, of course). Thus Cooke’s demise presented Francis with a serendipitous, macabre, and irresistible opportunity. He harvested Cooke’s skull for his collection and had Cooke’s headless body buried in St. Paul’s churchyard in lower Manhattan.

A good ten years after Cooke’s death, a New York theater company preparing a production of Hamlet found itself without a “Yorick.” Naturally, the producers approached the man known to possess the greatest collection of skulls in New York City: Dr. John W. Francis. And Francis had the remains of just the man for the job. Thus was George Frederick Cooke’s theatrical career reborn. His skull went on to appear in numerous productions of Hamlet, including one starring Edwin Booth (brother of John Wilkes Booth). Occasionally, it received billing in the theater program.

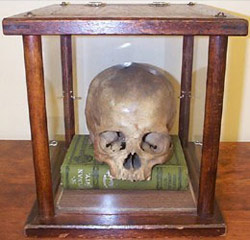

Today a monument paid for by the actor Edmund Kean marks George Frederick Cooke’s grave in New York City. Through a series of bequests, his skull made its way into the collection of the Scott Library at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, where it currently resides, after enjoying what the university calls “the longest active stage career in history.”

Leslie Gilbert Elman is the author of Weird But True: 200 Astounding, Outrageous, and Totally Off the Wall Facts. Follow her on Twitter @leslieelman.

Read all of Leslie Gilbert Elman’s posts for Criminal Element.