Some of the best works of noir, in both fiction and film, revolve around one troubled character. These doomed protagonists are often people who just can’t get along in the world, either forever or during one nightmarish, downward-spiraling cycle of events. Sometimes they’re basically good people who just ran into a nasty wave of bad fortune, sometimes they’re neither especially good nor bad but are just at odds with the rest of the world, and sometimes they’re rotten people that we vote for anyway because we know it’s the rotten world that made them that way.

Some of the best works of noir, in both fiction and film, revolve around one troubled character. These doomed protagonists are often people who just can’t get along in the world, either forever or during one nightmarish, downward-spiraling cycle of events. Sometimes they’re basically good people who just ran into a nasty wave of bad fortune, sometimes they’re neither especially good nor bad but are just at odds with the rest of the world, and sometimes they’re rotten people that we vote for anyway because we know it’s the rotten world that made them that way.

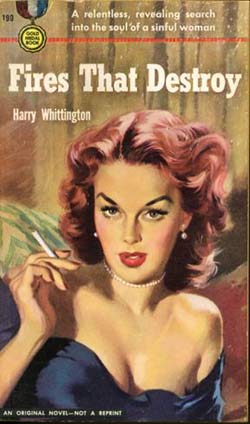

Fires that Destroy, Harry Whittington’s superb pulp novel from 1951, is no exception to the above-stated rule. But what’s unusual about it, for its time, is that the distressed lead character is a woman. Bernice Harper is plagued in such a way that she belongs in the second of the three classes described in the previous paragraph—neither good nor bad by nature, but just not getting along in life. Bernice is a 24-year old secretarial worker living in New York City. An embittered Plain Jane, she is frustrated by the fact that other women in her company get promoted over her, not because they do better work than she does, but because their faces are prettier than hers, their bodies more voluptuous.

The story is told in the third person, but there are times when the omniscient narrator goes into Bernice’s head and reveals her inner dialogue. In such a passage in an early part of the book, Bernice explains (to herself, not aloud) her personality development to someone she has just met. The following fragment is part of the explosion that erupts from her disturbed thoughts:

You become sensitive. You become so sensitive that two people cannot whisper across the room without causing you to be ill. You’re sure they’re talking about you. You want to run. You spend your whole life running from people. And all the time all you want inside is to run toward them and find them waiting, smiling, and their arms outstretched.

A turn occurs in Bernice’s life when a blind man named Lloyd Deerman comes to work for her company for a time, as a kind of short-term consultant. Bernice is assigned to provide clerical help to Deerman. Deerman likes her work and he likes to make plays for her. He likes Bernice so much that when he returns to his normal business (just what business any of the people in the book are in, is never made quite clear) at his home office, he offers to double her present salary if she’ll join him, as a live-in personal secretary. Bernice accepts the job, but there’s no way she’s going to let herself succumb to the ultimate humiliation of accepting the affections of a man who only wants her because he can’t see how unattractive she is. When she discovers in his house a secret stash of almost 25 grand in hard cash, wheels turn in Bernice’s warped brain, and before long the money has been moved to a place where she can get to it, and Deerman has a fatal “accident” inside the home.

There’s a police detective who suspects foul play and focuses on Bernice as the perpetrator, but he has no evidence against her, and Deerman’s estate is not pressing for an investigation into the death, so for the time being Bernice is free to do as she pleases. She’s led into the next big turn when she goes into a bank one day to change one of the 100-dollar bills from Deerman’s stash. The teller who makes the change for her is Carlos Brandon: a good-looking, jaded guy who earns more money as a gigolo than he does serving customers at the bank. Brandon takes note of the greedy way Bernice eyes him during their transaction, and he also takes note of the fact that she is a woman who is walking around with 100-dollar bills. Next thing Bernice knows, she’s going on a date with this beautiful man. Next thing after that, they’re fleeing to Florida and getting married.

All would be perfect for Bernice, except that Carlos cannot convince himself to get turned on by Bernice. Thus her intense animal desire for him is left to seethe. In some wildly raw scenes that must have shocked (or titillated, or both) Whittington’s readers back in the early ’50s, a sexual role reversal is shown as Bernice is made out to be a hungry animal that Carlos just can’t keep up with:

She pressed herself against him, feeling nothing but the excitement inside her, not even knowing how she was working her body against his.

He began to laugh and tried to push her away again. But Bernice knew. He had begun to respond. It didn’t make any difference that it was nothing but the hell in her that got him.

Her hands like talons, she grabbed the back of his head and jerked his mouth down against hers. His teeth cut her lips, thudded against her teeth.

So Carlos can’t get it up for Bernice. And, what’s worse, he’s a lush and a bad gambler. But Bernice can’t help herself; she still wants him. She, who’s never had a fair shake in her life, is so close to having everything, yet she can’t quite get there. Or, as the narrator sums it up:

Oh, she’d got away with murder, and she had Lloyd’s hidden money. But she had walked into hell: the hell of frustration. The kind of frustration that drove you insane. You knew what you wanted, you had it right with you, but it was rotten in the middle. It was no good. It was desire and excitement and sweet agony and it was always frustrated.

Okay, that’s enough plot rundown. Other things happen in the story, but I’ll leave that for the reader to discover. Fires That Destroy is hardly the only notable hard-boiled crime novel written by Harry Whittington. “The King of the Pulps,” Whittington penned an insane number of books in his life, something like 200, and was known for authoring nakedly intense tales that appeared between the covers of paperback originals. His best books pretty well define pulp fiction. Sometimes Whittington wrote too fast, and sometimes he spent too much time telling and not enough showing, but when he was on, he was a master of noir. In penning Fires That Destroy, he was so very on.

We’ll close with another passage from the book. Some of the best parts of this novel are the scenes inside Bernice’s head. A couple of these show troubled dreams of hers, like this one:

. . . And she would walk into a room. A room where inverted mushrooms were painted on the walls and ceilings and floors. Greens and reds and pink. There was something upsetting about the way they were painted. They stirred her. Upset her. Frightened her in a way that wasn’t fright at all.

Attracted and repelled by the gaudy room, she started across it. There was Rita Baehrs before her. She wanted to hate Rita. Rita had taken Al Brennan in bed in order to get Jane McMillan’s job. Rita had taken that job from Bernice. Bernice had a right to hate her. But Bernice smiled when she wanted to sneer. She hurried forward and Rita smiled and came running toward Bernice. But in the center of the room there was a small bridge between them. It was made of white plaster. It spanned an odd shaped pool of water. Red water. Blood red water. At the bridge Bernice stopped, shivering and cold. Across on the other side, Rita stopped, too. Rita beckoned. Then Bernice saw that the girl on the other side of the blood red pool wasn’t Rita Baehrs at all.

It wasn’t she. It was Bernice. Only she was so lovely that she hadn’t even recognized herself. She smiled and the lovely Bernice smiled back. She laughed. She began to laugh hysterically. The room shook with her laughter. Ripples spun around on the surface of the red pool. The gaudy mushrooms stretched and elongated and slithered on the wall like bright serpents. The room quavered and trembled as she laughed. She couldn’t stop laughing. She could only go on laughing until she cried. The tears wet her cheeks and she woke up laughing . . .

Brian Greene’s short stories, personal essays, and writings on books, music, and film have appeared in 17 different publications since 2008. He writes regularly for Shindig!, a U.K.-based music magazine with worldwide distribution. Greene lives in the Triangle area of North Carolina with his wife Abby, their daughters Violet and Melody, and their cat Rita Lee.

“You’ll Die Next” is another great one by Whittington.