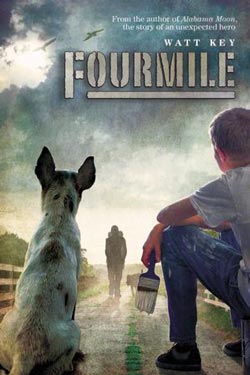

Fourmile by Watt Key is a middle grade suspenseful adventure book featuring a young boy and his dog (available September 18, 2012).

Fourmile by Watt Key is a middle grade suspenseful adventure book featuring a young boy and his dog (available September 18, 2012).

Watt Key returns to the themes of survival and justice in his newest novel for middle grade readers, Fourmile. Twelve year old Foster is attempting to adjust to a life without his father—an impossible task as he is confronted by his mother’s violent, abusive boyfriend, Dax. Hope arrives in the unlikely form of a stranger, a former soldier named Gary Conway, who quickly becomes part of Foster’s farm life in southern Alabama. Perhaps with Gary’s help, Foster can reconnect with his mother, get rid of Dax, and gain his life back. But Gary has his own secrets.

While there is no character thrown out into the wilderness in this story, Key very poignantly reminds the reader that surviving isn’t necessarily about who can build a fire out of twigs, or who can create shelters out of bath towels. No, the fight for survival in Fourmile is all about the fine line between peace and violence in human beings who live in regular houses, conduct regular business, and deal with everyday troubles.

The main character, Foster, is not immune from this struggle. In the opening sequence he has the choice to capitulate to his mother’s request and be polite to the man threatening to belt him—or he can retaliate on his own terms. Which he does:

“Your momma said to sit down,” he called after me.

But I kept on. Out the door and into the driveway until I was standing before his Chevy S10 pickup. I heard Dax pushing his chair back as I knelt and pulled a brick from the flower bed lining.

“Leave him alone, Dax,” Mother said.

“Hey!” he called after me.

I hurled the brick at his windshield where it made a crunching sound like a foot in wet gravel. The glass spider-webbed and the brick bounced off and skipped across the hood.

Very often in Fourmile, it is the hint of violence beneath the surface that shows Foster—and the reader—where the real danger lies. Dax is a man capable of dark things, and Key portrays this darkness without Dax physically assaulting any of the main characters (at least at first).

Dax is mean to Joe the dog, and the dog doesn’t like him. We all know to trust an animal’s instincts right? Turns out Joe is spot on. Dax doesn’t care about animals, children, or women. Key chooses to hammer home Dax’s personality in a scene at Dax’s shop. Dax is a taxidermist:

Suddenly the door swung in and he was standing there with his goat face, wiping his hands on his jeans. His thighs were smeared with blood. His arms were covered with it up to his elbows. He wore a white V-neck undershirt that was specked with red splotches and flecked with pieces of meat and jelly fat. I saw the shock in Mother’s face.

The dark atmosphere of Fourmile is intensified by the prose. Key’s language is old-school. Foster refers to his mother as “Mother” and not “Mom,” for example. The prose evokes an older time and increases the sense of isolation that Foster and his small family experience. Reading along, it’s difficult to imagine any of the characters whipping out a cell phone and texting anyone. It’s hard to picture a television existing in their world—in spite of the fact that Key mentions a television explicitly. The effect is that the characters feel alone, too far away from the police or any emergency help.

In fact, when Foster first meets the stranger who will change his small world, he’s painting a fence—which reminded me a great deal of Tom Sawyer. (Only Foster is more responsible and actually does the work that Tom so blithely handed off.)

The air was balmy and windy under a sky of rolling gray clouds. I was halfway down the front fence, sitting on my bucket, when I saw him coming up the road with his dog. I’d never seen a person walking this stretch of highway. Joe stood and trembled with an inside whine that meant he was either nervous, excited, or both.

“Easy boy,” I said to him.

I went back to painting, glancing up from time to time as they drew closer. After fifteen minutes I heard the man’s feet crunching the loose gravel on the roadside. I set my brush on the rim of the paint bucket and grabbed Joe’s collar.

The only people in the whole world at that moment are Foster with his dog and the stranger with his dog.

Key interweaves his characters, their isolation, and their possible futures into a tight-knit ball of stress. Foster lives in a world where guns have bullets, men have secrets, and mothers can’t protect their children. It’s a story reminiscent of Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet, Fred Gipson’s Old Yeller, and Wilson Rawls’s Where the Red Fern Grows—all have kids in situations where they are forced to make adult decisions.

See all our coverage of new releases in our Fresh Meat series.

Jenny Maloney is a reader and writer in Colorado. Her short stories have appeared or are forthcoming in 42 Magazine, Shimmer, Skive, and others. She blogs about writing at Notes from Under Ground. If you like to talk books, reading, publishing, movies, or writing feel free to follow her on Twitter: @JennyEMaloney.