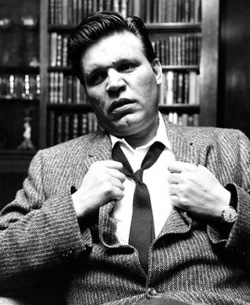

The man himself was, of course, more complicated than his onscreen persona. Born in Iowa in 1920, Brand was raised in Illinois, the eldest of seven children. After graduating high school, he enrolled in the Illinois National Guard and worked a series of odd jobs (shoe salesman, soda jerk) before he was inducted into the Army at the outbreak of World War II. During the war, he served as a platoon sergeant and amassed a distinguished military service record that surpassed that of any other film star before or since (with the exception of Audie Murphy, who became a film star because he was WWII’s most decorated soldier). Among other honors, Brand earned a Purple Heart, the Good Conduct Medal, the American Defense Service Ribbon, an Overseas Service Bar, a Service Stripe, and the Combat Infantryman’s Badge. (Later, when he became a film star, the Hollywood hacks would promote his service record—claiming falsely that he was the fourth most decorated American infantryman in the war—but Brand himself was always sheepish to talk about his wartime exploits and resented the way they were embellished.) His wartime service ended when he was wounded and nearly killed in battle. “I knew I was dying,” he later recalled. “It was a lovely feeling, like being half-loaded.” Honorably discharged, he came home and studied acting with the help of the GI Bill.

His entry into movies seemed a harbinger of ass-kickings to come, as an uncredited heavy in the 1949 narcotics thriller Port of New York. He followed that with “The Man With Nothing To Lose,” an episode of the anthology series The Bigelow Theater, about an escaped convict who breaks into the home of an elderly couple.

While Luther Adler is silk-smooth as the gangster at the center of the mystery, it’s Brand as Adler’s psycho henchman Chester, who steals the whole damn show. Brand has only a few scenes, but his orgasmic You-don’t-like-it-in-the-belly-do-you-Bigelow sniveling upped the ante on the way heavies would be played in the 1950s. Chester isn’t just mean, he’s a full-on nutcase who gets a psychosexual jolt from shooting people in the gut.

That same year you could find Brand playing an peculiar role in Preminger’s Where the Sidewalk Ends. He’s a thug/masseuse for a gangster played by Gary Merrill. He roughs up guys and then rubs down the boss. It’s an odd job, but who better than Brand to do it?

1952 found him in one of the all time great hoodlum line-ups. Kansas City Confidential is a cornucopia of head-thumpings curiosity of director Phil Karlson. John Payne stars as an ex-con trying to clear his name of involvement with a daring armored car robbery. He has to punch his way through a heap of bad guys that includes Brand, Jack Elam, Lee Van Cleef, and Preston Foster. The three man duke-out in a hotel room between Payne, Van Cleef, and Brand is one of the best scenes of its kind in a film noir.

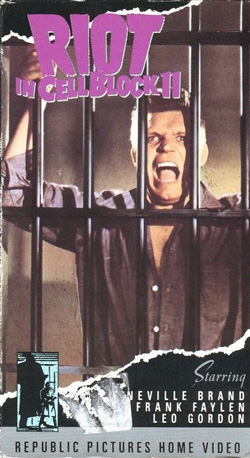

While Brand continued to notch up roles in noirs like Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye, The Mob, and The Turning Point, he also branched out into Westerns and war films (including Billy Wilder’s classic Stalag 17). In 1954 he got a rare starring role as the leader of a prison uprising in Don Siegel’s Riot in Cell Block 11. Looking beefy even by his own impressively beefy standards, Brand turns in a solid performance as Dunn, the mastermind of a large scale riot. Although Dunn has staged the riot as a way to draw media attention to the plight of the inmates, the film doesn’t seem particularly interested in representing that plight. Brand works hard, but his character is underwritten. It’s difficult to find the center of Dunn. Is his revolt really a public relations ploy? Does he really trust the system to keep its word to him?

While Brand continued to notch up roles in noirs like Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye, The Mob, and The Turning Point, he also branched out into Westerns and war films (including Billy Wilder’s classic Stalag 17). In 1954 he got a rare starring role as the leader of a prison uprising in Don Siegel’s Riot in Cell Block 11. Looking beefy even by his own impressively beefy standards, Brand turns in a solid performance as Dunn, the mastermind of a large scale riot. Although Dunn has staged the riot as a way to draw media attention to the plight of the inmates, the film doesn’t seem particularly interested in representing that plight. Brand works hard, but his character is underwritten. It’s difficult to find the center of Dunn. Is his revolt really a public relations ploy? Does he really trust the system to keep its word to him?

The missed opportunity of Riot in Cell Block 11 may help explain why Brand, although one of the great supporting players in noir, never really broke out of the thug tier the way someone like Richard Widmark did. Much like Elisha Cook Jr., Brand was destined to occupy the edges of the frame, stealing scenes, making things more interesting, but never really seizing the spotlight.

As the classic noir era wound down at the end of the fifties (including henchman roles in good late era films like Cry Terror!), Brand moved on to the greener pastures of the Western, where he basically took his knuckle-dragging thug act into the old West. He banked an impressive run of lowlifes and sweaty scumbags (including an entertaining part in the underrated Anthony Mann flick The Tin Star, opposite Henry Fonda).

Once the sixties hit, Brand found himself working primarily in television. He played Al Capone on The Untouchables and did a guest spot on The Virginian playing wisecracking Texas Ranger Reese Bennett, a role so popular it was spun-off into the series Laredo. Sadly, Brand’s on and off set drinking caused production problems and Brand left the show early.

His drinking seemed to stabilize a bit after that, and Brand kept on working in television and film. His last film, just a few years before his death in 1992, was a cheapie horror flick called Evils of the Night in 1985. Brand played . . . a psychotic henchman.

The key to his greatness is that he was, in fact, a serious actor. “I don’t go in thinking [my character is] a villain,” Brand told the writer William R. Horner. “Nobody thinks he’s a villain. Even a killer condones what he’s done. So I just create this human being under the circumstances that are given . . . Everybody just condones his own actions.”

See more posts in the Film Noir series.

Jake Hinkson, The Night Editor, is the author of Hell on Church Street.

Great post! Thanks for the memories.

It’s nice to see Neville Brand get some credit. I’ve loved watching him for years, but you don’t see him mentioned anywhere at all. He was a lot of fun to watch, whether he was the good guy or the bad guy. Loved that gravelly voice too. One of my faves was “Five Gates to Hell” but I don’t think I’ve seen it since the 70s.

It’s worth seeing Tobe Hooper’s Eaten Alive (1976) just for Brand’s nutso portrayal of the aging owner of an rundown motel in some nightmarish swamp. Plus he’s even got a “pet” crocodile.

Brand’s performance in D.O.A. really was a feat of noir excellence. The scene in which he and O’Brien are in the car is nothing short of horror-film stuff. Brand knew how to act. He also was the main saving grace in the two-season TV western Laredo. Brand proved he had a deft touch at light comedy in the show. Check out the book “Shoot Em Up: Memories of the American Television Western” on Amazon for more on Brand and the show.