“Want to hear something strange?”

“Want to hear something strange?”

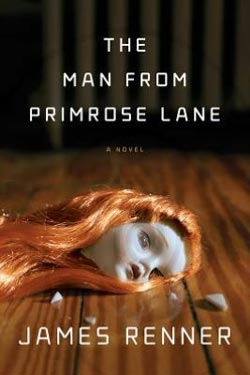

So asks the sometimes-narrator of James Renner’s The Man From Primrose Lane about two-thirds of the way through the book. To even so much as tell you who, specifically, uttered those words would spoil one of the flat-out weirdest reads you’re ever likely to experience, as is evidenced by the reply:

David looked worried. “How much stranger does it get?”

David, you have no idea. The Man From Primrose Lane is a slippery novel—difficult to pin down, and nigh impossible to synopsize without venturing into major spoiler territory. But since we’re all here, howsabout I try?

The story centers (nay, spirals) around bestselling true-crime author David Neff. Neff’s sole book, which exonerated an executed man and placed a serial killer behind bars, had a seismic effect on the literary and legal community alike, but he hasn’t written a word since. Partly because of the meds that blunt his creativity—meds prescribed after the trauma of what his book uncovered—and partly due to the suicide of his beloved wife, which left him reeling. Four years after Elizabeth’s death, David’s editor nudges him back toward writing, dropping a case on his lap too juicy to resist: the story of a murdered hermit known only as the Man from Primrose Lane. No one knows who he was, or why he was killed, but the more David investigates, the more he comes to realize the dead man’s fate is inextricably intertwined with his own—and with his wife’s.

At first blush, the setup suggests straight-ahead thriller, but as the tale unfolds, you soon realize you’re reading either a surreal science-fictional rumination on love, loss, fate, obsession, and identity, or one man’s chilling descent into insanity. Either way, it’s as ambitious as it is off-kilter. But what I enjoyed most was not the broad strokes; it was Renner’s ability to conjure the fantastical from the prosaic—his way, I think, of tipping his hand that all is not as it initially appears. Take, for example, our introduction to the titular hermit, on the day his death is discovered:

He was mostly known as the Man from Primrose Lane, though sometimes people called him hermit, recluse, or weirdo when they gossiped about him at neighborhood block parties. To Patrolman Tom Sackett, he had always been the Man with a Thousand Mittens.

Sackett called him the Man with a Thousand Mittens because the old hermit always wore woolen mittens, even in the middle of July. He doubted most people had noticed that the old man wore different woolen mittens every time he stepped out of his ramshackle house. Most people who lived in West Akron averted their eyes when they saw him or crossed the street to avoid walking by him. He was odd. And sometimes odd was dangerous. But Sackett, who had grown up just a few houses north of Primrose Lane, had always been intrigued. In a binder somewhere in his basement, alongside boxes of baseball cards and his abandoned coin collection, was a detailed list of each mitten he’d seen the old man wear—black mittens, tan mittens, blue mittens with white piping, white mittens with blue piping, and, once, in the middle of some long-ago May, Christmas mittens with candy canes and reindeer.

Nothing in that passage is otherworldly in nature, but the net effect of such peculiar imagery sure makes it seem so. And as the book progresses, Renner slowly ratchets up the ratio of odd to ordinary in a way that keeps the audience as disoriented as his quick-witted but unbalanced protagonist. Witness this creepy bit, as David explores the woods behind the home of a suspected killer:

It was dark, but there was also a darkness. He felt it in his bones, in a dull aching in his head, the taste of copper in his mouth, like dried blood. This place had remained untouched throughout modern human history, undeveloped by white man. Had the Indians avoided this place, too? Was it some hallowed or evil ground that people avoided subconsciously? How much was David imagining simply because he knew how close this place was to a den of true evil? Not much—even the birds felt it.

As he was about to turn back, David happened upon the clearing.

It was lined with giant white elm trees that had miraculously avoided the disease that felled their Ohio cousins: great, formish, idyllic elms, the likes of which David had never seen and never would again. It was a large circle, perhaps a hundred feet in diameter, carpeted with bluegrass that bended and lolled in the dank, wet hot. It was so bright in the center that David’s eyes hurt and he was forced to squint so much his vision was reduced to a thin slit. It was several minutes before he noticed the stuffed animals.

The animals were crucified upon the elms.

David realizes the animals are arranged to face the center of the clearing, at which resides an ancient tree stump. Carved into that stump is one word: Beezle.

He felt an urge to say the word aloud, to hear the sound of the word, the name, in this clearing. But the thought of the repercussions stopped him. What would happen here if he muttered such an invocation? He did not care to know. If this was the place Beezle called home, he didn’t want to meet him. Or It. And he certainly did not want to call it.

And through the wrongness of the clearing, he felt something else. Or imagined it. The sensation surfaced as a picture in his mind as he tried to draw out the analogy. He thought of two bar magnets, placed such that their opposite polarities were close to touching. Slowly, the magnets scooted toward each other, gathering speed, and collided, then rested, at last. In some way, he was one of those magnets. And this clearing. No, this stump, the Thing it represented. This darkness was the other magnet and it pulled at him, promising a final rest for his soul if he would only surrender to it.

David awoke to himself, just as he was about to step onto the stump.

Your standard fare, this ain’t. But if you want to take a trip down the rabbit-hole and find out just how far it goes, then The Man From Primrose Lane awaits…

Chris F. Holm was born in Syracuse, New York, the grandson of a cop who passed along his passion for crime fiction. He wrote his first story at the age of six. It got him sent to the principal’s office. Since then, his work has fared better, appearing in such publications as Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, and The Best American Short Stories 2011. He’s been an Anthony Award nominee, a Derringer Award finalist, and a Spinetingler Award winner. His first novel, Dead Harvest, is a supernatural thriller that recasts the battle between heaven and hell as Golden Era crime pulp.