In December of 1893, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was guilty of the premeditated and willful murder of Mr. Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, a consulting detective of some public renown. “I have had such an overdose of [Holmes] that I feel towards him as I do toward pâté de foie gras, of which I once ate too much, so that the name of it gives me a sickly feeling to this day,” he had said previously. He wasn’t just whistling Dixie. In a reader response famed for its brevity and the universality of the sentiment among Victorian fans, “You brute,” a woman penned to the author, whose greater work—he imagined—was unfairly shackled to Holmes.

(Perhaps unfairly, SPOILERS abound for those daring to read on.)

The suggestion that people wore mourning bands in the streets to honor the fallen character may be apocryphal. But if I had a mourning band, I’d likely be sporting it today. So maybe it isn’t. And the Strand Magazine did lose approximately 20,000 subscriptions.

“You brutes,” I now address Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, creators of BBC’s hit series Sherlock. But “brutes” as in the High and Holy Poobahs of Most Excellent, Thoughtful, Affecting, and Generally Heart-Incinerating Creators of Dramatic Television Content, Department of Ferocious Winning. Just to be clear.

But “The Adventure of the Final Problem” is problematic for filmmakers in a deeper sense also, if an obvious one; Doyle permanently revived Holmes ten years later, in “The Adventure of the Empty House.” So many holes exist in this account of how and why Holmes purported to be dead for three years—from trivia regarding reversed boots to the thorny conundrum that Holmes was never cruel, yet faked his demise to his closest friend with about as much feeling as one would expect from Hannibal Lecter—that ninety percent of any Reichenbach adaptation’s screen time cannot be devoted to how, but why.

And away we go.

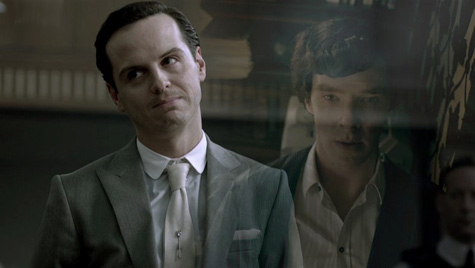

Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock Holmes, once a loner consulting detective and now an internet celebrity with a friend, a mother figure, and a colleague (John, Mrs. Hudson and Inspector Greg Lestrade respectively), has been called to testify as an expert witness against Andrew Scott’s barking insane Jim Moriarty. A consulting criminal and an utterly believable Napoleon of Crime, Moriarty is apparently in possession of a key code that allows him to break into impregnable fortresses (he looks particularly fetching in the Crown Jewels). Sherlock offers obnoxious though airtight testimony, and Moriarty presents no defense whatsoever, but our modern Jim is a psychopathic terrorist, and despite these facts, manages to get himself acquitted. Why did he allow himself to be imprisoned in the first place, Sherlock asks? What follows are a series of Moriarty-designed tests of Sherlock’s brilliance and—ultimately—his heart.

But I can’t talk about that yet. I have more review to write, and strange weather patterns are threatening to make it rain on my laptop.

TV Tropes discusses the nemesis or arch enemy at length as the “evil counterpart” or “what our hero could have become as a result of a very small change in his backstory,” and BBC Sherlock’s Jim makes glorious hay out of the theme of mirroring. “You are me,” he says to his foe during the dramatic conclusion. Not “you are like me,” but you are me. They aren’t identical, of course, but it’s a brilliant piece of theatre—both men want very little apart from the thrill of a cracking good game, and the fact that Sherlock’s disregard for humans when solving a puzzle is common knowledge makes this assertion not an insult, but a key plot point. Jim can hurt Sherlock at least in part because Sherlock has allowed himself to be almost universally loathed. That the men are in some ways opposites is given weight and complexity due to the fact they are so much akin.

Further tropes than mirroring, however, make this duel to the death a compelling one. Sherlock and Jim chat over tea following his release and Jim purrs sweetly, “Every fairy story needs a good villain.” Grimm’s fairy tales recur as clues throughout in a poetic touch almost childlike in its simple affection for storytelling. Doyle’s works are fairy tales in the truest sense, in that they teach us about heroes and scoundrels and sacrifice and death, and the lengths to which brave men must go to rid the world of evil. Jim has promised Sherlock a “final problem,” and our protagonist’s descent into a personal Hades is a foregone conclusion.

The John Watson of the canon devoted the majority of his life to chronicling the aloof, but endlessly fascinating, man responsible for the criminal relics that ended up in their butter dish and the bullet holes that appeared in their wall. The four novels and fifty-six short stories are in many ways about devotion, and watching the friendship be sundered was bad enough on the page—“The Reichenbach Fall” has rendered it with such affection and beauty that watching it is akin to watching your own open-heart surgery. Martin Freeman’s portrayal of John’s grief is going to earn him another BAFTA nod, or I will personally take it into my hands to lock every nominating committee member in a room where Jack and Jill plays continuously at top volume on a giant screen. “I was so alone,” he tells Sherlock’s grave. And he is alone again.

In life, John refuses to allow Sherlock to be discredited, even when Sherlock himself is complicit in the gambit. In death, he can barely speak the words aloud that his friend is gone. He isn’t gone, of course, and Gatiss has already confirmed a series three—but without Sherlock, John is fighter without a battle, a veteran without a war, one half of the single functioning person they became when they met. And he is without Sherlock—canonically speaking, of course—for a very long time.

In the torturously-long meanwhile we have in store before an adaptation of “The Empty House” graces our tellies, Martin Freeman will immortalize a hobbit with a knack for riddles and Benedict Cumberbatch will embody an enormous lizard in his company. Will they muse, I wonder, just how Moffat and Gatiss plan to get Sherlock and John out of this mess? Because I will be rocking myself to sleep with Granada Television’s version, moisturizing my cracked little heart with the moment when everything is all right again.

Holmes will buy Watson’s practice out from under him using the sneaky cousin technique, and whisk him back to Baker Street, where violins croon in the wee hours and dressing gowns can exist in the shade “mouse.” Moffat and Gatiss have given us a bravura rendition of The Adventures-era Holmes—is it any wonder that I long for reunion, and for the metaphorical equivalent of 1895?

U.S. Airing update (5/21/12): If you’re distraught, and think you might be able to console yourself with Sherlock and John crocheted and handcuffed dolls until Season 3, enter our comments contest for your chance to win this adorable amigurumi!

Lyndsay Faye, author of Dust and Shadow and The Gods of Gotham, coming March 2012 from Amy Einhorn Books/Putnam. She tweets @LyndsayFaye.

Read all of Lyndsay Faye’s posts.

Oh, it’s raining on your laptop too. I thought I was the only one! [s].. Or not.[/s]

It will indeed be a very long time before we see the conclusion, but.. At least we have six epsiodes which to absorb our minds into and in the meanwhile, Mr. Benedict and Mr. Martin can work their afts off.

For us.

For the fandom.

[s][/s]

[s]AND DAMN YOU MOFFAT AND GATISS! YOU ALMOST BROKE THE HEARTS OF THE SHERLOCKIAN FANDOM! SHAME ON YOU![/s][s][/s]

Now please excuse me, while I go[s] and lock myself in a room with my friends and watch these episodes over and over and over and over and over.. and over agai And again and again AND CRY Damn it[/s]. and get myself a tissue.

Those crazy weather patterns! The brutes! 😉

As always, wonderful post! I was delighted and utterly surprised by “Jim”. The great thing about the original character was that he wasn’t suspicious (That sweet little professor? A criminal mastermind?), and Jim works so well because he’s nothing like what we modern viewers were expecting!